Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

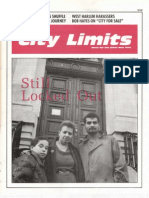

City Limits Magazine, December 1994 Issue

Încărcat de

City Limits (New York)0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

504 vizualizări32 paginiCover Story: Down on the Street, Geoffrey Canada and scores of Harlem residents look to rebuild the community for the future by Andrew White.

Other stories include Steven Wishnia and Andrea Payne on the devastation left by Giuliani's October Plan; Ed Tagliaferri on the benefits and drawbacks of Westchester's workfare program Giuliani looked to replicate; Laura Washington on the lack of community jobs brought to Fort Greene, Brooklyn despite Metrotech promises; Jill Kirschenbaum on East Brooklyn tenants fighting to stay in their homes; Harold DeRienzo on the ineffectiveness of the ongoing community housing movement; Mary Ellen Hombs' book review of "The Homeless," by Christopher Jencks.

Drepturi de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentCover Story: Down on the Street, Geoffrey Canada and scores of Harlem residents look to rebuild the community for the future by Andrew White.

Other stories include Steven Wishnia and Andrea Payne on the devastation left by Giuliani's October Plan; Ed Tagliaferri on the benefits and drawbacks of Westchester's workfare program Giuliani looked to replicate; Laura Washington on the lack of community jobs brought to Fort Greene, Brooklyn despite Metrotech promises; Jill Kirschenbaum on East Brooklyn tenants fighting to stay in their homes; Harold DeRienzo on the ineffectiveness of the ongoing community housing movement; Mary Ellen Hombs' book review of "The Homeless," by Christopher Jencks.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

504 vizualizări32 paginiCity Limits Magazine, December 1994 Issue

Încărcat de

City Limits (New York)Cover Story: Down on the Street, Geoffrey Canada and scores of Harlem residents look to rebuild the community for the future by Andrew White.

Other stories include Steven Wishnia and Andrea Payne on the devastation left by Giuliani's October Plan; Ed Tagliaferri on the benefits and drawbacks of Westchester's workfare program Giuliani looked to replicate; Laura Washington on the lack of community jobs brought to Fort Greene, Brooklyn despite Metrotech promises; Jill Kirschenbaum on East Brooklyn tenants fighting to stay in their homes; Harold DeRienzo on the ineffectiveness of the ongoing community housing movement; Mary Ellen Hombs' book review of "The Homeless," by Christopher Jencks.

Drepturi de autor:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 32

December 1994 NewYork's UrbanAffairs NewsMagazine

. Return to MetroTech Have Nonprofits Sold Out?

I

C i ~ V Limirs

Volume XIX Number 10

City Limits is published ten times per year,

monthly except bi-monthly issues in June/ July

and August/September, by the City Limits

Community Information Service, Inc., a non-

profit organization devoted to disseminating

information concerning neighborhood

revitalization.

Editor: Andrew White

Senior Editor: Jill Kirschenbaum

Associate Editor: Kim Nauer

Contributing Editors: Peter Marcuse,

James Bradley

Intern: Amber Malik

LayoutIProduction: Laura Gilbert

Advertising Representative: Faith Wiggins

Office Assistant: Seymour Green

Proofreader: Sandy Socolar

Photographers: Steven Fish, Eve

Morgenstern, Gregory P. Mango

Sponsors:

Association for Neighborhood and

Housing Development, Inc.

Pratt Institute Center for Community

and Environmental Development

Urban Homesteading Assistance Board

Board of Directors':

Eddie Bautista, New York Lawyers for

the Public Interest

Beverly Cheuvront, City Harvest

Errol Louis, Central Brooklyn Partnership

Mary Martinez, Montefiore Hospital

Rebecca Reich, Low Income Housing Fund

Andrew Reicher, UHAB

Tom Robbins, Journalist

Jay Small, ANHD

Walter Stafford, New York University

Doug Thretsky, former City Limits Editor

Pete Williams, National Urban League

Affiliations for identification only.

Subscription rates are: for individuals and

community groups, $20/0ne Year, $30/Two

Years; for businesses, foundations, banks,

government agencies and libraries, $35/0ne

Year, $50/Two Years. Low income, unemployed,

$10/0ne Year.

City Limits welcomes comments and article

contributions. Please include a stamped, self-

addressed envelope for return manuscripts.

Material in City Limits does not necessarily

reflect the opinion of the sponsoring organiza-

tions. Send correspondence to: City Limits, 40

Prince St., New York, NY 10012. Postmaster:

Send address changes to City Limits, 40 Prince

St., NYC 10012.

Second class postage paid

New York, NY 10001

City Limits (ISSN 0199-0330)

(212) 925-9620

FAX (212) 966-3407

Copyright 1994. All Rights Reserved. No

portion or portions of this journal may be

reprinted without the express permission of

the publishers.

City Limits is indexed in the Alternative Press

Index and the Avery Index to Architectural

Periodicals and is available on microfilm from

University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor,

MI 46106.

2/DECEMBER 1994/CITY LIMITS

Crain's Delirium

A

mong the many Single Room Occupancy hotels on the Upper West

Side are a pair called the Marion and the Clinton Arms. Not entire-

ly pleasant places to live, they are owned by private landlords and

operated as businesses designed to make a profit.

So it came as a surprise to some when the two were referred to as non-

profit social service facilities in a recent article in Crain's New York

Business. Of course, the authors hid their agenda by not actually naming

the hotels; they simply wrote, "Three clients of facilities on the Upper

West Side stabbed a man trying to stop them from robbing a car," using the

incident as one more example of non profits running amok in civilized

neighborhoods. These "clients" were tenants of the two hotels.

The Crain's article was part of a series blasting the nonprofit social

service sector with a shotgun spray of innuendo and red-baiting concoct-

ed by executive editor Steven Malanga and reporter Robin Kamen. Their

disregard for accuracy reflects exactly the sort of dishonesty that drives the

current reactionary attack on nonprofits.

For nearly 20 years, City Limits has exposed corruption in the nonprof-

it sector, particularly in the politically connected social service empires of

people like former City Council Member Ramon Velez and state

Assemblyman Angelo Del Toro. But with a masterful trick of innuendo,

Malanga and Kamen used the example set by these poverty pimps to bol-

ster their own attack on quality organizations with excellent track records

whose only sin has been to provide homes for poor and disabled New

Yorkers.

The irony is that corrupt social service empires lorded by politicians are

invariably based in low income neighborhoods of color where the average

citizen's political influence is limited. Yet Crain's primary targets-

Volunteers of America, the Cooper Square Committee, the Institute for

Community Living, Community Access and West Side Federation for

Senior Housing-operate in neighborhoods with a growing percentage of

well-off residents. Guess where the influence lies.

For a closer look at the misrepresentations of this NIMBY blitz, see

Robert Kolker's article in last month's City Limits. If you haven't got a copy,

call-we'd be happy to send you one.

But more importantly, for those of our readers who are leaders in the

business community or work with top executives, please consider the

implications of all of this. Now is the time to speak out. Write a letter to

Crain's, or encourage your boss to write one. If you have been reading City

Limits, you know the scope of poverty in this town. Malanga and Kamen's

misguided offensive strengthens an increasingly vicious assault on the

least powerful people of our city. You might ask them, and the NIMBY

activists who helped craft their articles, what, exactly, they would prefer.

Reopening inhumane mental institutions? New orphanages? And perhaps

we shouldn't bother to provide housing and services for people with AIDS.

Instead, we should send them to die on the steps of the New York Stock

Exchange.

* * *

A clarification: our November 1994 article on Family Court, "Guilty

Until Proven Innocent," did not properly identify Beth Ornstein. She is a

training specialist at the New York State Child Welfare Training Institute

at the Center for Development of Human Services at Buffalo State College.

Cover design by Lynn Baldinger. Photos by Gregory P. Mango.

FEATURE

Down on the Street 16

An intensive grassroots effort is underway to reclaim one city block

in Central Harlem. Now the city wants to tryout its latest housing

initiative there. Strange bedfellows, or a marriage made in heaven?

by Andrew White

BUDGET REPORT

Blitzkrieg 6

Mayor Giuliani's October Plan will gut city programs already reel-

ing from the last round of budget cuts.

by Steven Wishnia and Andrea Payne

WESTCHESTER REPORT

Mixed Reviews 8

Everyone's talking about Westchester's workfare program. Is it real-

ly as good as they say it is? by Ed Tagliaferri

PIPELINE

History Repeats 12

Residents of Fort Greene want to know what happened to all of those

jobs they were promised, back when MetroTech was just a develop-

er's fantasy. by Laura Washington

In Nehemiah's Way 22

There's a struggle of biblical proportions going on in East New York

between a powerful church group and a tiny tenants' association.

Guess who's winning? by Jill Kirschenbaum

COMMENTARY

Cityview

Managing the Crisis

Review

No Solution at All

DEPARTMENTS

Editorial

Briefs

Branching Out

Loan Fund Milestone

2

5

5

Letters

25

by Harold DeRienzo

27

by Mary EUen Hombs

28

Professional

Directory 29,30

Job Ads 30,31

6

12

16

CITY LlMITSIDECEMBER 1994/3

Free Water

Surve

The New York City Department of Environmental Protection

encourages all residential building owners and home owners in

New York City to take advantage of a free Water Survey Program.

You can reduce your water/sewer bill by saving water lost to

plumbing leaks.

N. no charge, we will perform a water leak survey of your home

or building and install free water-saving devices when

applicable. In less than half an hour, we will survey your

plumbing for leaks and install:

, FREE high efficiency shower heads

, FREE low-flow faucet aerators

, FREE water-saving toilet devices

Call 18005457740 today

or

(718) 937-6600

to Schedule Free Water Leak Survey only

Water Survey Teams have picture 1.0.s and wear uniforms

Participation in this program is voluntary DE:P

New York City

Department of

Environmental Protection

W. Guliani, Mayor

Marilyn Geller,

For all other water, sewer, air and noise issues call 718-DEP HELP

4/DECEMBER 1994/CITY LIMITS

Environmental ac:tiYists from the Federation to Preserve the Greenwich WIage

Waterfront & Great Port held a demotlStl atiUl'l to protest deweIopment plans for

the Hudson River shoreline by a subsidiary of the state Urban Development

Corporation. The group bumed an oversize check for $80 million, representing

money the city may lose to the federal government if curTent plans go foIwanl.

Loan Fund Milestone

ACCION New York has just

passed the $1 million mark in loans

to Latin<H>wned small businesses in

the Bronx, Manhattan, Brooklyn and

Queens.

A privately funded nonprofit orga-

nization, ACCION New York began

lending to low income micro-entre-

preneurs in July, 1991. The aim was

to make credit available to people

who, with limited collateral or credit

history, were unable to secure loans

j from traditional commercial banks.

~ To date, ACCION has offered some

! 400 loans to help finance bodegas,

street vendors and other small-scale

operations.

Although the loans can be as

diminutive as $1,000 for an individ-

ual borrower, over 60 percent go to

groups of three to five borrowers,

which allows the would-be entrepre-

neurs to take out a Single, more siz-

able loan at cheaper interest rates

and distribute the money among

them. At the same time, the group

acts as an alternative to collateral,

providing peer pressure and support

to ensure that loan payments are reg

ularly met. In three years of lending,

only $13,945 has been written off.

The loans have given small busi-

ness owners the leverage to reach a

greater number of clients, increase

their inventories and diversify their

product base.

Branching Out: I.A.F. takes a new tack

According to Delma Soto, execu-

tive director of ACCION New York,

this kind of incremental growth is

the essence of microenterprise.

A national citizens group that has

fostered community action among

church congregations for decades is

grOWing fast in the New York region,

and has begun to organize among a

wide array of nonreligious neighbor-

hood-based groups as well.

At an October 30th rally on the

World Trade Center plaza in lower

Manhattan, attended by an

estimated 10,000 members

of the Industrial Areas

Foundation (lAF), the main

focus was on holding politi-

cians accountable for

reforming government job

training programs and creat-

ing new Jobs. But leaders

also revealed a new direc-

tion in their activist work,

announcing plans to bring

youth groups, recent immi-

grants and tenant associa-

tions, among others, into

the fold.

We can see the day

when there will be 50,000

or 75,000 people in an

open space large enough to

Edgecombe Avenue force the

Department of Transportation to

enforce the long-ignored ban on

commercial vehicles in their residen-

tial neighborhood. Prior to HIT's

involvement, the association had

tried for a year to resolve the prob-

lem and had gotten "the royal run

around," Inman says. By holding

hold them, not just 10,000," ................................ .....

says IAF national staffer FCIIIIIddoa ............... TnIde c.IIr.

Mike Gecan. The IAF cur-

rently has seven member organiza-

tions in the New York region, includ-

ing East Brooklyn Congregations,

South Bronx Churches and Harlem

Initiatives Together (HIT).

Howard Inman of HIT has already

started putting the new strategy into

practice. Over the past few months,

his group has helped a block associ-

ation on 150th Street and

house meetings, developing leaders

and encouraging members to

demand a meeting with the city offI-

cial who could really accomplish

some change, HIT also helped the

group get new traffic lights and

speed limit signs installed.

Now they have a more ambitious

goal-ridding nearby Jackie Robinson

Park of drugs and prostitution.

Had the people from 150th

and Edgecombe approached him

for help in years past, Inman says

he would have had to ask

whether they belonged to a

church in the area, or suggested

they join a congregation affiliated

with IAF, such as Covenant

Avenue Baptist. "But some peo-

ple are not interested in

church, he says, "and

there was a large body of

people we were not

speaking to.

Members of the

block association have

each paid $25 in dues to

join what is being called

Metro IAF." The relation-

ship between Metro IAF

and the other IAF affili-

ates in the New York

area is stili being

defined, Gecan says.

IAF leaders based

their decision to move in

o ... ~ this new direction partly

on what they see as

~ widespread frustration

with the t w ~ r t y politi-

cal system, Inman says.

"People need someplace

to go. We're saying this is where

they should put their efforts,

instead of the Democratic or

Republican parties, he explains.

"We want to be able to hold

senators and congressmen

accountable. Given our method

of turning people out, we'll be a

force to be reckoned with.

Robin Epstein

"This is a way to help people help

themselves," Soto says. The loans

have created or strengthened

approximately 231 jobs to date.

Furthermore, Soto stresses, over 35

percent of ACCION loans have gone

to women entrepreneurs, helping

them realize an increasingly secure,

if not totally independent, future.

Romalinda Rivera is a case in

point. Currently receiving public

aSSistance, Rivera is studying for a

job in the health services industry.

She is also operating a small retail

clothing business out of her apart-

ment with two other women, and

they just received their third loan

from ACCION-$3,OOO to buy more

merchandise and further expand

their growing business.

"Business is good," says Rivera.

"I plan to leave welfare soon:

At the other end of the spectrum

is Paloma Communications. Last

year, four freelance writers took out

a $6,000 loan to start a company

that produces newsletters and mag-

azines for a variety of agencies and

organizations in the Dominican

community, including the Dominican

Chamber of Commerce. When busi-

ness started to expand rapidly, the

group went back to ACCION for a

second loan, this time for $40,000.

Without the first loan the compa-

ny would never have gotten 'off the

ground, says Nelson Muniz, one of

the owners of Paloma Communica-

tions. Today, the company employs

two staffers, has just hired three

more, and plans are in the works to

expand operations further into mail

order and telecommunications.

Amber Malik

CITY LlMITSIDECEMBER 1994/5

Blitzkrieg

By Steven Wishnia and Andrea Payne

Giuliani's October Plan leaves a trail of devastation

in the agencies that serve the city's poorest residents.

The verdict is in: Mayor Rudolph

Giuliani's plan to cut $1.1 billion from

the city's budget would leave many of

the city's social services with little

more than Tinker Toy support. By the

time City Limits reaches newsstands,

the City Council should have taken a

vote on the proposal, known as the

October Plan. What follows is just a

small sample of the cuts currently on

the table. Some of them may be

excised before December 1, according

to Giuliani budget director Abraham

Lackman. Most will not. We have not

included here some of the cuts that

have received wide attention, includ-

ing an estimated 80 percent

reduction in contracts with the

Department of Youth Services.

2

One important note: With the

election of Governor George

Pataki, observers fear any new

help for the city budget from

Albany is now just a fantasy. If

the October Plan is any indica-

tion, they add, the mayor doesn't

seem to want the aid anyway: his

proposal cuts millions from

services already heavily support-

ed by state and federal matching

funds.

o Day Care:

At a time when Mayor Giuliani

seeks to decrease welfare rolls,

advocates predict his plan to

eliminate 1,982 subsidized day

care slots could force some low

income parents to leave jobs and

school and seek public assistance

instead. And while the city will realize

an immediate savings of $6.2 million,

it will also lose $18 million in match-

ing federal and state funds.

These cuts would close between 20

and 30 day care centers, advocates say.

This will impact heavily on low

income working families, says Nancy

Kolban, executive director of Child

Care Inc. "As more women enter the

workforce, we're talking about cutting

back the services available to them.

[Any] economic development strategy

cannot work without good child care

services," Kolban says, adding that

children will lose a much-needed

jump on their education.

6/DECEMBER 1994/CITY LIMITS

o Emergency Food:

Eliminating the city's Emergency Food

Assistance Program would save $2.1

million this years and $6.5 million in

the next. But approximately 100 of the

city's 600 soup kitchens and food

pantries would close immediately, esti-

mates Liz Krueger, associate director of

the Community Food Resource Center.

The ability to feed the 250,000 to

300,000 people annually who depend

on these meals is further jeopardized

because the federal government is

slashing its own donations of surplus

food by two-thirds next January.

Hungry people may have a more

difficult time finding free meals

because the city's cuts would also lead

to the closing of the Food and Hunger

Hotline referral service and a food

stamp outreach program that brings

millions of dollars in federal aid to the

city's poorest residents.

o Mental Health:

Programs for alcoholics, the mentally

retarded and developmentally dis-

abled would lose all city support

under the October Plan, saving $4.4

million. And providers of all other

mental health services face an overall

16.4 percent reduction in program

funding. These cuts would save $1.7

million this year and $2.2 million in

fiscal 1996.

As yet, no one knows which pro-

grams would face elimination under

the universal cut, but estimates are

that as many as 20,000 people will be

affected when the dust settles, says

Phillip Saperia, executive director of

the Coalition of Voluntary Mental

Health Agencies. This is because every

dollar cut by the city is likely to lead to

cuts in matching funds from the state

and charities. "By cutting $2.2 million

in city support, the mayor may be

eliminating as much as $14 million in

state aid, Medicaid and private fees, as

well as $85 million in state reinvest-

ment dollars specifically aimed at

New York City," he explains.

At the Staten Island Mental

Health Society, 500 of its 2,000

treatment slots for severely trau-

matized children-many of them

homicidal, suicidal or victims of

abuse-would be eliminated,

says executive director Kenneth

Popler. "These cuts are unbeliev-

able," he adds.

o Housing:

Along with substantial reductions

in staffing at the Department of

Housing Preservation and Devel-

opment, the October Plan would

eliminate city-funded legal ser-

vices (amounting to $1 million

this year, $1.3 million next year)

for poor tenants who do not

receive federally-funded public

assistance. It would also deeply

wound the Community Consultant

Program, eliminating $2.5 million in

contracts with neighborhood groups

that organize and assist tenants. More

than 80 percent of this program would

be cut by next year.

Tenants in private buildings would

be hit hardest, says Anne Pasmanick of

the Community Resource and Training

Center. "The bottom line is there's not

going to be a lot of help," she says. The

city would also cut the maximum

amount of back rent it will cover for

welfare tenants from 12 months to

four, an annual savings of $4.5 million.

Scott Sommer of Legal Services calls

this cut "a classic example of being

penny-wise and pound-foolish. To not

pay $3,000 in rent arrears and

then pay $3,000 a month for a

shelter? I can't explain it."

o Homelessness:

"There'll be more families sleep-

ing on the floor of the Bronx

Emergency Assistance Unit," says

Steve Banks, coordinator of the

Legal Aid Society's Homeless

Family Rights Project. The $6.5

million in cuts will reduce

payments to nonprofit shelter

operators, delay the opening of

some single room occupancy facil-

ities for single men and women

and eliminate the long-planned

expansion of an intensive case

management program, that helps

families relocating to permanent

housing deal with problems such

as tracking down missing public

assistance checks or requesting repairs

and other services. Banks says the cuts

in the latter program could send more

families back to the shelters. "The most

nonsensical cuts are the ones in pro-

grams that prevent people from being

homeless," he says.

o Family Preservation:

Mayor Giuliani's plan would eliminate

treatment programs providing services

to drug-addicted women and their

children. The city expects to save $1.6

million in this fiscal year and $2.5 mil-

lion in the next. However, these bud-

get reduction measures could easily

end up costing the city more money in

increased foster care and boarder baby

costs, as well as several million dollars

in state and federal funding

A chief goal of family rehabilitation

is to keep children out of foster care by

providing mothers with services such

as drug treatment, day care and job

training. The programs now serve 700

families with 2,000 children. A "char-

itable estimate" is that 10 percent of

these children would be placed in fos-

ter care immediately as a result of the

cuts, says Mike Arsham, director for

social service policy for the Council of

Family and Child Caring Agencies. In

addition. newborns now discharged to

parents taking part in the program

would instead remain in costly hospi-

tal care, says Carmen Gaines, program

director of Community Services for

Children and Families at St. Luke's

Roosevelt Hospital.

o Corrections:

The October Plan would eliminate all

city-funded drug treatment in the jails,

including beds for 900 prisoners, as

well as all other inmate therapy and

counseling. Supervision in jail recre-

ational areas would be cut by one-

quarter, and the city's work release

program would be eliminated.

"For a law-and-order mayor,

[Giuliani is] taking steps that will

probably contribute to increasing

crime in the streets," charges Robert

Gangi of the Correctional Association

of New York. According to Gangi, the

number of guards will be reduced by

almost one-sixth by next June-just

about the same time the inmate popu-

lation, swelled by "quality of life"

arrests, is projected to pass 20,000.

The city would also cut $1.5 million

from alternatives-to-incarceration pro-

grams, according to Elizabeth Gaines

of the Osborne Society, which admin-

isters two such programs.

o Hospitals:

The city would cut $107 million from

its $356 million annual contribution to

the public hospital system. The effect

would be primarily in staffing; offi-

cials are looking for 2,500 to 3,000 of

the system's 40,000 workers to take

buyouts. Harlem Hospital, which has

lost patients to both expanded out-

patient clinics and increasingly

Medicaid-friendly private hospitals,

will lose one-sixth of its beds and

more than 200 workers, says Marshall

England, head of the hospital's com-

munity advisory board. The jobs lost

would be primarily in what John

Ronches of the Committee of Interns

and Residents calls "invisible, but

important" jobs, such as technicians

and transporters, though nurses would

also be among them.

This is adding insult to injury,

administrators say. The city's

contribution already fails to

cover the expense of mandated

services such as medical care for

police, firefighters and prisoners.

o Sanitation:

The big hits here are in the recy-

cling program, says Larry Shapiro

of the New York Public Interest

Research Group. The city plans to

cut $8 million this year and $13

million next year by reducing

public education and outreach

programs, cutting enforcement

officers by one-third, and termi-

nating an intensive recycling

pilot program in Park Slope,

Brooklyn. Recycling collections

in the Bronx, Upper Manhattan

and parts of Brooklyn would also be

cut from weekly to biweekly.

Shapiro argues that while educating

people about recycling doesn't direct-

ly pick up garbage, these cuts will

"ultimately condemn the program to

failure."

o Transit:

The October Plan cuts $230 million in

city aid to the Transit Authority

between now and July 1996; previous

cuts included $52 million in operating

aid and $750 million in capital funds.

No specific services have been slated

for the guillotine, says Gene Russianoff

of the Straphangers Campaign, but

"when you cut $230 million from their

budget in a year and a half, there are

going to be some serious repercus-

sions." The casualties could include

the $1.25 fare, the proposed monthly-

pass and double-fare-zone discounts,

and maintenance and repair work. 0

Steven Wishnia is a frequent

contributor to City Limits. Andrea

Payne is a freelance writer based

in Brooklyn.

Advertise in

Ci ty Limits!

Call Faith Wiggins

at (917) 253-3887

CITY LlMITSIDECEMBER 1994/7

Mixed Reviews

Workfare rhetoric targets cheats, but much of the savings

comes from shifting costs to Washington.

H

eriberto Rios sweeps the

floors inside the Cottage

Gardens public housing com-

plex in Yonkers and says he

is satisfied, for now.

It's been two years since he held a

full-time job and this assignment, as

part of Westchester County's workfare

program, is keeping him busy. "I'd

rather be working than in the house,"

says the 33-year-old Yonkers resident.

During the last nine months, Rios

has worked 20 hours a week for the

county, mopping floors, raking leaves

and performing general maintenance

work around this municipal housing

project. In return, he has gotten his

$400 monthly Home Relief check.

That's about $4.60 an hour.

Rios' situation is typical of many

other people in Westchester's five-year-

old workfare program, called Pride in

Work. The program has been touted by

many reform-minded Republicans as

an example of how government can

save money and promote the impor-

tance of work among adult recipients

of state- and county-funded Horne

Relief, the welfare program that sup-

ports primarily single men and

women, as well as childless couples.

The program has caught the eye of

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, who

announced recently that he intends to

use Westchester's workfare program as

a model for New York City'S. He hopes

to save $80 million a year in welfare

payments by exposing fraud and keep-

ing people who could otherwise find

And critics also note that Rios' situa-

tion mirrors exactly what's wrong with

the program. He's getting no job train-

ing, only manual labor assignments.

And the county is using cheap labor

instead of hiring full-time workers,

undercutting the unionized municipal

workforce. Moreover, if Rios has a

problem with the job, they add, or if he

really can't work because of a physical

or psychological problem, he could

lose his benefits and end up homeless.

Reelection Campaign

Pride in Work was unveiled in early

1989 and became a cornerstone of

Republican County Executive Andrew

O'Rourke's reelection campaign that

year and again in 1993. He won both

times.

Men and women on Home Relief are

given jobs ranging from sweeping

offices to clerical work, from flushing

hydrants to painting fences. They work

for the county, other municipalities and

even some nonprofit organizations. If

they don't show up for their assign-

ment, they are eventually dropped from

the rolls.

With these rigid requirements in

place, welfare cheats can be easily

weeded out, says Westchester Com-

missioner of Social Services Mary

Glass. People working off the books

are no longer able to keep their under-

the-table jobs and still collect Home

Relief, she explains.

To crack down on cheats, the coun-

ty developed a computer program for

By Ed Tagliaferri

covered instead by Supplemental

Security Income (SSI), a form of Social

Security that is funded by the state and

federal governments. Home Relief, on

the other hand, is funded by the state

and county governments with no con-

tribution from the federal government.

As a result of the shift, officials say,

Westchester has avoided $15.6 million

in welfare costs. They make no apolo-

gies for the move. In fact, O'Rourke has

often criticized the state for passing

unfunded mandates down to local

governments and has publicly reveled

in the opportunity to pass this cost

back up the line.

Weeded Out

To demonstrate Pride in Work's suc-

cess, officials note that in 1989, the

county spent $44.6 million on Home

Relief. This year, the county budgeted

$38.3 million. Meanwhile, between

1990 and this year, the number of coun-

ty residents on general assistance grew

by less than one percent, to 7,638 peo-

ple. During the same period, with the

metropolitan area's economy in free-fall

much of that time, New York City's

Home Relief numbers jumped nearly 60

percent, to more than 243,000, accord-

ing to the state Department of Social

Services.

Glass also says that 15,000 people

have left or been bumped off the Horne

Relief rolls since 1989, either because

they found jobs, were eligible for

another form of assistance or were

weeded out as cheats.

In an era when welfare reform has become a political mantra, Pride in Work has kept the Home

Relief rolls stable, cut its cost to the county and reaped millions of dollars worth of free labor.

employment off the Horne Reliefrolls.

Indeed, workfare has been a politi-

cian's dream in Westchester. In an era

when welfare reform has become a

political mantra, Pride in Work has

kept the Horne Relief rolls stable, cut

its cost to the county and reaped mil-

lions of dollars worth of free labor.

But observers point out that a large

portion of the county's savings has

been achieved by simply shifting costs

to the state and federal governments,

ultimately saving taxpayers nothing.

S/DECEMBER 1994/CITV LIMITS

checking the background of anyone

applying for assistance. Employment

and tax records are reviewed, as are

welfare case histories. The clients are

screened by social workers to deter-

mine whether or not they have any

drug or alcohol problems or physical

disabilities that might prevent them

from working.

This is where the biggest single sav-

ings has been achieved: over the past

five years, the county has found that

3,000 people on Home Relief could be

However, while about 9,000 of those

people stayed off the rolls, the rest

came back and reapplied at some point.

Among them are nearly 2,000 people

who challenged their loss of benefits,

arguing that they were wrongly

removed from the rolls. Only 200 have

won their appeals following a hearing.

Advocates for welfare charge the

hearing process is unfair, and the high

number of failed appeals is proof.

While the county advises people that

they can have legal representation at

their hearings, none is provided.

Jerry Levy of Westchester-Putnam

Legal Services says that during the

past year, his office has represented

fewer than a dozen people at appeals

hearings. And the people who make it

to the appeals process in the first place

are only the most visible part of the

problem, he notes. He believes that

many men and women with legitimate

disabilities are being knocked off the

Home Relief rolls without even

attempting to defend themselves.

"This is such a beaten population," he

says. "They don't challenge things. "

Paula Roberts, a lawyer with the

Center for Law and Social Research in

Washington, D.C., agrees. "Part of the

problem is that if you are really dis-

abled, you're probably not a prime

candidate for advocating [for your-

self], " she explains.

Levy contends that a good lawyer

could overturn the county's actions in

80 percent of the cases mainly by chal-

lenging the medical evaluation of the

client. But free legal representation for

the poor in the hearing process would

run counter to the demands of welfare

reform. He suggests, as do many other

critics, that the actual intent of work-

fare programs is to disqualify people

from receiving their benefits, thus keep-

ing costs down.

Stepping Stones

Workfare has received mixed reviews

locally and nationwide, according to

Roberts and other researchers. She says

that some workfare programs work well:

"They can be stepping stones for getting

a real job. " But at the same time, she

adds, "What you are really doing is dis-

placing workers. What you're doing is

taking jobs away from other workers

and getting the work done at lower

wages with no benefits. "

The union representing West-

chester County municipal employees

shares these concerns. "You wonder .. . is

it easier to lay off our workers when

they know they've got these low-paid

welfare people?" asks Anita Manley,

spokeswoman for the Civil Service

Employees Association, which repre-

sents 6,500 county workers.

Rafael Salas, a laid-off landscaper

who also rakes leaves and sweeps up at

Cottage Gardens, is the perfect exam-

ple. Salas says he doesn't mind the

work. But when he performed the same

job professionally, he earned about

twice what he's currently getting paid

through workfare. About all he can

hope for now is a full-time job at

Cottage Gardens should one open up,

he says.

Most participants in Pride in Work

receive little or no training-only 860

Home Relief recipients attended train-

ing classes last year. Commissioner

Glass says that those who are identi-

fied as willing and able to learn new

skills are offered job training in com-

puters, office work and the health care

fields. All of the training programs are

funded by the state or federal govern-

ment. "I think we're training all the

people who are trainable," she says.

Meaningful

One study of workfare programs

across the country indicates that most

participants feel the tasks they have

been given are "meaningful."

"It may not have taught welfare

recipients new skills, but neither was

it make-work," reported the September

1993 study, published by the

Manhattan-based Manpower Demon-

stration Research Corporation. The

report also noted that most of the peo-

ple surveyed would have preferred a

real job, and said there was "little

evidence" that the work experience

provided by workfare programs led to

consistent employment or had any

effect on future earnings.

Still, there's no denying that some

participants find some benefit to the

program. At Cottage Gardens, the six

workfare staffers all say they are

pleased to have something useful to

do. Walter Nichols, unemployed for

two years from the building trade, says

he enjoys using his maintenance skills

around the development, though he

and the others would rather have real

jobs. "There are no jobs anywhere, "

agrees Rios, with a shake of his head.

"I wish I could get a job here." D

Ed Tagliaferri is a staff reporter for

the Gannett Westchester newspapers.

Subscribe to

Ci ty Limits!

Call (212) 925-9820

Specializing in

Community Development Groups,

HDFCs and Non Profits.

Low Cost Insurance and Quality Service.

NANcvHARDV

Insurance Broker

Over 20 Years of Experience.

80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, NY 10504,

914,273,6591

CITY LlMITSIDECEMBER 1994/9

~ ...

~ ,

CHASE

Community

Development

Corporation

The Chase Community Development

Corporation Finances Housing and

Economic Development Projects,

including:

New Construction

Rehabilitation

Special Needs Housing

Homeless Shelters

Home Mortgages

Small Business Loans

Loan Consortia

For information, call the

Community-Based Development Unit

(212) 552-9737

We Look Forward to Your Call!

10/DECEMBER 1994/elTV LIMITS

G1JTSY.

INCIS

Life inside a city-owned crack den ... public agencies cut-

ting deals for private developers ... landlords who col-

lect the rent and let their buildings rot. Each month,

CITY LIMITS probes the misguided public policies and

inefficient bureaucracies besetting New York. But we

don't think it's good enough just to highlight the muck.

CITY LIMITS looks for answers. We uncover the stories

of activists and local organizers fighting to save their

neighborhoods. That's why CITY LIMITS has won nine

journalism awards in recent years. Isn't it time you

subscribed?

YES! Start my subscription to CITY LIMITS.

$20/one year (10 issues)

$30/two years

Business/Government/Libraries

$35/one year $50/two years

Payment enclosed. Add one issue

to my subscription-free I

Name

Address

: City State _ Zip :

CITY LIMITS, 40 Prince Street, New York, NY 10012

CITY LlMITSIDECEMBER 1994/11

History Repeats

Did MetroTech create jobs for Fort Greene's unemployed?

Hardly. Now it's Atlantic Terminal's turn.

W

hen executives of the

Forest City Ratner devel-

opment group applied for

federal subsidies to build

an office and academic complex in

Downtown Brooklyn eight years ago,

they estimated the project would cre-

ate 1,071 new jobs for area residents. In

a fact sheet accompanying the

the park are nice. But that doesn't feed

and clothe people."

According to the developer, an affir-

mative action program for construc-

tion companies and laborers has

created a number of short-term jobs for

local residents. But as far as full-time

office work or employ-

By Laura Washington

Seedy Stretch

Downtown Brooklyn has undergone

a dramatic transformation since the

decade began. Sleek office towers and

a brand new university campus have

shot up on the once seedy stretch of

land between the off ramps of the

Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges.

Several major financial companies

have moved here from the canyons of

Wall Street and the broad avenues of

midtown Manhattan to a new life in

Brooklyn. Lauded by the Brooklyn

borough president's office for reviving

downtown and establishing the area as

the third largest business center in

New York City, optimistic developers

have even come up with a new

moniker-"Wall Street East." Two

additional office towers have gone up

nearby since MetroTech broke ground

in 1989, and there are two more pro-

application ,

they even dug

up some dra-

matic statistics

underlining the

neighborhood's

desperate need

for an economic

booster shot.

After all, 24 per-

cent of the pop-

ulation had in-

comes below the

federal poverty

line.

Today, Metro-

Tech is bustling

with some 10,000

__________ .. that include more

office space, a

hotel and retail

stores.

office workers. But most if not all of

those employees came east when

companies like Chase Manhattan

Bank, and Bear, Stearns and

Company relocated their headquar-

ters from Manhattan. Meanwhile,

the residents of Fort Greene-the

neighborhood literally across the

street from MetroTech, home to the

4,900 residents of three public

housing projects and the most

impoverished area bordering

Downtown Brooklyn-say they are

still waiting to experience the econom-

ic benefit of the new, $1 billion com-

plex. Asked if MetroTech's arrival has

benefited the community they live in,

the prevailing answer here is a

resounding "No."

"The impression was that MetroTech

would create jobs for local people,"

notes Kathy Peake, an aide to state

Assemblyman Joseph Lentol. "Fort

Greene has not seen the fruits of that."

"Forest City Ratner sponsors free

concerts in Fort Greene Park," adds

Niger Campbell, a resident of the

neighborhood and an organizer with

the Fifth Avenue Committee, a low

income housing group. "Concerts in

12/DECEMBER 1994/CITY LIMITS

ment in the service industries is

concerned, observers say there's little

evidence of an impact. Even the self-

contained design of the complex has

created a sense of division here, with

broad blank walls facing eastward

toward the Ingersoll and Whitman

Houses on the other side of Flatbush

Avenue.

"[MetroTechl has isolated itself

from the community as if in a

fortress," observes Fort Greene resi-

dent Benjamin Irvin. "And conse-

quently, a very wary relationship

exists between MetroTech employees

and the community."

MetroTech.is a

joint effort of the

City of New York,

Polytechnic Uni-

versity and the

Forest City Ratner

Companies , a

Cleveland-based

real estate devel-

opment company

headed by former

commissioner of

consumer affairs

Bruce Ratner. The

project was con-

ceived in the 1970s

by Polytechnic's president, Dr. George

Rugliarello. He envisioned a commer-

cial and academic complex that would

meld the resources of Polytechnic-an

engineering school that lacked a cam-

pus but boasted a high-powered facul-

ty and a reputation for doing extensive

research in the telecommunications

and computer fields-with the needs

of major financial institutions looking

for a competitive edge in the global

marketplace.

To add bait to the hook-this, after

all, was a time when companies were

moving their offices out to the suburbs

"The impression was

in search of lower rents and better tax

breaks-the city offered what ultimate- that MetroT_

ly came to $329 million dollars' worth

....... create L.I- L_ of incentives to the developers and "", ,.,.,. ..,.-

prospective tenants, including a 13-

year exemption from real estate taxes,

a 12-year abatement of the commercial

rent tax and a 12-year corporate tax

credit of $500 for every employee

local people

Fort Gree ... has aot

moved to the Brooklyn offices. seen the fruits of thaI."

Today, four years into the project, 80

percent of the ll-building site is com-

plete. The Polytechnic campus is here,

along with the offices of Brooklyn

Union Gas and the Securities Industry

Automation Corporation (SIAC),

which processes financial transactions

for the New York Stock Exchange.

The development did have its casu-

alties. Approximately 200 residents

were bought out and relocated from

the site, as were some 60 businesses

and five governmental agencies when

the area was razed in 1989.

But the project's supporters argued

the losses would be more than offset

by improvements to the area, which is

bordered on the west by Jay Street and

the nearby Brooklyn Borough Hall, on

the east by Flatbush Avenue Extension

and Long Island University, and on the

north by New York City Technical

College. The infusion of thousands of

MetroTech employees into the area

would create a trickle-down effect on

downtown retail businesses, they said,

including the discount bazaar along

nearby Fulton Street. And it would

spur an increased demand for more

goods and services-and, in turn,

more jobs.

Static Opportunities

Such an effect has yet to be seen,

however. Employment opportunities

for local residents in retail remain sta-

tic, according to reports in Crain's New

York Business. Toys 'R' Us is now a

cornerstone store at the Gallery, for-

merly the Albee Square Mall, which

Forest City Ratner purchased in 1990

and renamed in an effort to move it

upscale. Vacancy rates in the shopping

center have steadily declined since

then-from 40 percent in 1990 to 10

percent today. But store owners say

business has not increased significant-

ly, and many small retailers have been

replaced by larger national chains such

as Foot Locker and Barnes & Noble.

The proprietors of the century-old

Gage & Tollner restaurant, a few blocks

to the west, hoped to see their business

flourish with the coming of Metro-

Tech's minions. They didn't; the own-

ers were forced to file for bankruptcy

protection in March of last year.

Ken Adams, the new executive

director of the Downtown Brooklyn

Business Improvement District, insists

that it is still too early to measure the

impact of MetroTech on retail business

in the area, though he acknowledges

growth has been slow. "We still have a

long way to go. Not enough of the

workers are going to Gage & Tollner, or

A&S. Our job is to try to change that."

Permanent Jobs

Most of all, there is little to indicate

that MetroTech has created anywhere

near the more than 1,000 permanent

new jobs promised to local residents

back in 1986, or the services necessary

to prepare and place people in posi-

tions with the financial and informa-

tion services businesses located there.

The city's Economic Development

Corporation established the Downtown

Brooklyn Training and Employment

Council (DBTEC) in 1992 to address

such needs. But since it opened 18

months ago, it has placed only about

90 people in permanent positions,

reports director Earl Haye.

Haye explains that many of the

companies at MetroTech tend to go to

commercial temp agencies when they

have low-level positions to fill; that

way they can avoid the soaring costs of

health coverage and other fringe bene-

fits. In addition, he says, many compa-

nies have had hiring freezes since his

office opened.

Most significant, he adds, is the fact

that there are few low-skill positions

available. "We are telling training

groups that they have to prepare their

students to do more. Basic data entry

skills are not enough, for example. The

companies want them to be able to do

customer service too, and have good

communications skills." The people

MetroTech companies are hiring have

advanced computer skills, Haye says-

skills that the 40 job-training groups

affiliated with DBTEC are not

equIpped to provide.

On the construction side, Forest

City Ratner claims to have more than

met its goal for an aggressive affirma-

tive action program. According to the

company, 30 percent of the construc-

tion contracts are currently with busi-

nesses owned by women or minorities,

and the construction workforce is

roughly 50 percent women and

minorities. More than one-third of the

construction laborers are from the

neighborhood, they add.

City Council Member Mary Pinkett

believes MetroTech has been benefi-

cial. "To improve a community, you

need an economic infusion. Mom and

Pop stores alone can't do it. To the

degree that MetroTech has brought in

growth businesses, it has greatly

enhanced the area in which we live.

The beginning is there."

Pinkett says Forest City Ratner

should be commended for its contribu-

tion to recreation and education in the

area. Some tenants of MetroTech have

formed partnerships with Brooklyn

schools, for example, such as Chase

Manhattan's Smart Start program, a

scholarship initiative for 20 graduating

high school seniors planning to attend

Brooklyn colleges. And Forest City

Ratner sponsors a summer job program

that hires high school students

part time in maintenance and clerical

positions.

But there are other areas in which

residents feel they have been neglect-

ed. Michael Boyd, director of the Fort

Greene Community Action Network,

recalls that a portion of the $8 million

Urban Development Action Grant

(UDAG) awarded to Forest City Ratner

was earmarked for the beautification

of the area surrounding MetroTech.

However, Boyd says, "The funds went

everywhere but east. Nothing past

Flatbush Avenue got attention. How

far do you have to go to get to the sur-

rounding community? We are right

across the street." Forest City Ratner

spokesperson Joyce Baumgartner,

however, denies that UDAG monies

were ever designated for that purpose.

And while Borough President

Howard Golden recently announced

that the downtown area will be getting

a face-lift-plans are being made to

add distinctive street signs, new side-

walks, updated lighting, and trees to

create a unified visual image-critics

point out that, once again, Fort Greene

is not included in the plan.

Eric Blackwell, editor of the Fort

Greene News and a member of the

local community school board, calls

CITY LlMITS/DECEMBER 1994/13

the situation "the tale of two cities,

separate and unequal."

"Who is looking out for our commu-

nity?" he asks. "The development

plans should have had attached to

them the inclusion of new parks, new

schools. In this case, all that has been

an afterthought. That puts all the cards

in the developers' hands, and that

doesn't make sense. Their bottom line

is profit."

No Systematic Effort

Residents are now wondering if the

$530 million Atlantic Terminal pro-

ject, another city-subsidized Forest

City Ratner undertaking on a 24-acre

site located above the nearby Flatbush

Avenue terminal of the Long Island

Railroad, will provide the kind of

opportunities they say MetroTech has

failed to realize. Community groups

monitoring the project are skeptical.

The problem, says Brad Lander,

executive director of the Fifth Avenue

Committee, is that there has been no

systematic effort made to pinpoint

exactly what the developers' responsi-

bilities are to the community, and

what can be done in the future if they

''The funds went

------

everywhere but east.

far do you

have to go to get to

the _lTOIInding

community? We are

don't meet these responsibilities.

"We sent the Borough President's

Advisory Committee on Atlantic

Terminal a letter with a ton of ques-

tions," he says. "We asked them to set

some targets in terms of the creation of

meaningful career track positions, hir-

ing and training programs, and what

they would do if they didn't meet

those targets. What kind of community

structure would be set up?" So far,

says Lander, his group hasn't received

a reply.

"Public officials so strongly want

development, they are unwilling to

press for those kinds of agreements or

concessions," Lander continues. "We

have a federal, state and city corporate

development policy with no clue how

to link-or the willingness to ensure-

community jobs for people of color."

Reap the Benefits

It will take more than a ribbon-cut-

ting ceremony to insure that Fort

Greene residents reap the benefits they

feel they have coming to them. John

Mollenkopf, a professor at the City

University of New York's Graduate

Center and an urban renewal special-

ist, is not optimistic.

"There are ways, for example, to

link the New York City school system

to the telecommunications and com-

puter industries," he explains. So far,

however, those connections have not

been made. Mollenkopf suspects that

MetroTech will turn out to be a "clas-

sic urban renewal project, good for

companies and generating a plus for

the city fiscally. But it [won't] impact

Fort Greene. There are lost opportuni-

ties." 0

Laura Washington is a copy editor

at Vogue.

CITIES IN CRISIS ECONOMIC DEfiCIT

HEAlTH CARE IN AMERICA

Ntw York University is an ajfimraliw

ocoonlequal opponunity instiUIUm.

THE ENVIRONMENT

Tackle the Issues.

At New York University's Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, you will

acquire the skills necessary to tackle the issues of a professional career in public, nonprofit, and

health organizations. Programs of study include. Public Administration. Urban Planning

Health Policy and Management. You can study full or part time; financial aid is available.

Career placement services are available to all Wagner students. Find out what the Wagner

Graduate School of Public Service can do for you.

Call1-800-771-4NYU, ext.709, Monday Robert F. Wagner

through Friday or send in the coupon below. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC SERVICE

r-----------------------------,

I 0 Public Administration 0 Urban Planning 0 Health Policy and Management 0 Saturday Programs 0 Doctoral Programs I

I New York University NAME I

Robert F. Wagner Graduate

I School of Public Service ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE I

I 4 Washington Square North I

New York, N. Y. 10003 TELEPHONE SOCIAL SBCURITY NUMBER UOS

L _____________________________ ~

14/DECEMBER 1994/elTY LIMITS

Congratulations to

Jill Kirschenbaum,

Senior Editor of City Limits

and recipient

of the NASWs 1994

Carroll Kowal

Journalism Award

for enhancing

the public's awareness of

Social Conditions

in New York City.

Comtru1ity Development Group

CITY LIMITS/DECEMBER 1994/15

By Andrew White

"Mother Pearl" Chambers outside her window on West 119th Street

The tale of one block in Central

Harlem where residents are stirring

the coals of community action-

and preparing to bargain with the

city over who will own their homes.

H

alfway down West 119th Street in Central

Harlem, past the streetcorner dice game

and a row of gutted brownstones with

cinderblocks in place of doorways, the mother

of all compassion leans out from her first

floor window.

"Mother Pearl" Chambers spends a good part of most

every day with her elbows set on the window sill, keeping

an eye on the men, women, boys and girls that pass by on

her block between Fifth and Lenox avenues, where she has

lived since 1945. To the many homeless and poor people

16/DECEMBER 1994/CITY LIMITS

who stop by her window day after day, she provides food,

clothes, comfort and wisdom; sometimes even a few dollars.

On a chill November morning, a young and very preg-

nant Jeanette Ortiz stops beside the stoop of Number 48 to

speak with "this woman Pearl, my mentor." Ortiz is home-

less, just out of prison after a short stay for selling drugs.

She tried to get a place in a shelter, but it didn't work out.

So she is still homeless, walking the length and breadth of

the block where she has lived off and on for much of her

life. Pearl encourages her to be careful and stay warm, and

hands her a few things.

"I can see myself like her someday," Ortiz says with a

beaming smile and a nervous hand clutching a pack of

Newport cigarettes. "She's aware of the people that need

help. She's given me shoes and clothing from her house."

Ortiz is barely 20. Up close her worn thin face indicates

a brutal life. As she walks away, Pearl's eyes betray a deep

sadness. "She's on drugs," she says. "I've known her since

she was so young, she's lived in so many buildings on this

block." When Ortiz was arrested, she was living in an aban-

doned house across the street without heat or water. Her

baby is due in December. "I told her I think it will come

sooner," Pearl says, quietly. "I don't know how much we

can help her. But we have to try."

A

ccording to conventional wisdom, Pearl

Chambers and Jeanette Ortiz represent the old

and the new, two sides of life in America's poor

urban neighborhoods: the disappearing history

of communal responsibility and support net-

works, and the rise of violence, drug addiction,

unplanned motherhood and dependency. But conventional

wisdom is often wrong.

The small gifts of compassion emerging from Number 48

are to some a sure sign of Harlem's greatest strengths, of the

spiritual core of a community written off as lost long ago.

For many years Mother Pearl was one of a small number of

people here striving to make a difference: she organized

annual block parties for 20 straight summers, arranged

decent burials for scores of indigent men and women who

died alone, and still regularly sweeps the sidewalk clear of

litter. But today she is part of a blossoming movement of old

and young alike building on the community's strengths,

reversing the long decline of West 119th Street.

"It's beginning to grow again. It's getting clean again.

There are young minds bringing us together," says

Marguerite Gordon, a local church leader who is 86 years

old and has lived in her brownstone home on the north side

of the block for more than five decades. "It can be a good

block. It has been in the past, so why not now?"

There are two strands of change threading through the

fabric of West 119th Street: first, the people of the block

coming together, building new relationships with one

another and learning to advocate for repairs in housing,

better services and a stronger sense of mutual responsibil-

ity; and second, the city government sketching plans for a

new direction in housing policy. West 119th between Fifth

and Lenox is near the top of the current list of blocks being

considered for the first round of the Giuliani administra-

tion's initiative to rehabilitate and sell city-owned build-

ings to small businessmen and women, as well as to neigh-

borhood-based nonprofits and tenants themselves. If

Harlem's tumultuous politics don't reverse the city's

course, the program could be in full swing here

within a month or two.

At the point where the two strands knot togeth-

er is Community Pride, a government-funded

group experimenting with innovative strategies

for rebuilding a spirit of community, organizing

tenants and providing a broad array of youth pro-

grams and social services. A project of the

Rheedlen Centers for Children and Families, a

leading provider of youth development programs,

Community Pride is one of a number of compre-

hensive community-building initiatives under-

way around the country combining social services

and advocacy with organizing. It is also one of the

neighborhood groups the city hopes will facilitate

the new housing initiative.

Of course, when this kind of enterprise is

funded by government-as many say it ought to

be-questions inevitably arise. The story of

Community Pride, still in its infancy as a community action

organization, offers a revealing glimpse into the tremen-

dous possibilities and the complicated dilemmas that face

those engaged in such innovative approaches to neighbor-

hood revitalization.

"These groups are testing a hypothesis," says Sherece

West, program associate for the Annie B. Casey Founda-

tion, which is funding similar projects nationwide. "If you

put resources in place with the right partners, engage the

residents in the right way and have the willingness of the

city to work with you, can you move a successful commu-

nity building agenda? It's still a bit too soon to say."

Community Pride has brought together a disparate array

of people on West 119th Street, including many who live in

the 19 city-owned buildings on the block (all of them taken

from tax-delinquent landlords during the last decade and a

half). The tenants want much-needed repairs, but are

apprehensive about the city's new housing plan.

"The city can't just come in and do anything they want,"

explains Rosetta Carey, a tenant on the block for 11 years

and super of five city-owned buildings. "They have to come

in and speak with the people. That's the way it has to be."

This leaves Community Pride-whose government fund-

ing comes through a contract with the tenants' landlord, the

city's Department of Housing Preservation and Development

(HPD)-in a potentially delicate position. The way HPD

Commissioner Deborah Wright's new plan for selling city

properties plays out on West 119th Street promises to be a

test case for the entire concept of government and commu-

nity collaboration.

Lee Farrow, the lead or-

ganizer with Community

Pride, and Geoffrey Canada,

Rheedlen's president, say

they are committed first and

foremost to the people of

West 119th. "We're going to

stay with that community,

and that's regardless of

whether we keep city fund-

ing or not," says Canada. "If

we find out that this does

"The city can't

just come in and

do anything

they want .... They

have to come

in and speak

with the people. "

CITY LlMITSIDECEMBER 1994/17

g

z

~

a:

~

a:

Cl

not work for the community, we will do whatever is possi-

ble to change this process."

poverty."

So Rheedlen set out to see if it could change the nature of

poverty in one small part of the city: a block on West 119th

Street where housing conditions are bad and drugs and vio-

lence loom large over everyday life, but where there is also

a strong foundation on which to build. For one thing, there's

a well-established church-Emmanuel A.M.E.-as well as a

cooperative apartment building that tenants purchased from

construction dumpster by the curb on the north

side of the street is overflowing with garbage

gathered from rear alleyways and yards, tossed

from apartment windows by tenants too lazy to

take their refuse down to the garbage cans, says

Willie Johnson, the super

for four of the city buildings. He is a "While "ou might

quiet, solidly built man who can be , ,

the city, standing as a model of what

could be for the residents of the remain-

ing city-owned buildings. There is also a

block association, numerous homeown-

ers and elders like Mother Pearl with a

wealth of experience and devotion to

their community.

found on the sidewalk almost every have to come in

day, keeping an eye on things. He has

lived on the block since 1961. "Some of on the short term

these people don't care," he says, in a and deal with

tone that says this should be no sur-

prise to anyone. the symptoms that 119th Street lies on

But a people's capacity to respect the edge of one of the

their home can depend on whether it is poverty produces, poorest census tracts

a home worth respecting, argues Farrow. h I I in New York City. In

"Home should be an environment t e on y rea cure the four-block area

where you feel like a human being. But is changing the stretching southward,

the physical conditions here are so bad, the median annual household income is

you can see gaping holes, ceilings falling nature of poverty. " only $8,856. More than one-third of the

down," she says. "People do not like residents are children and at least three-

living in bad conditions. But they end quarters of them are being raised by

up conforming to them because they a single parent, according to the 1990

don't feel they have a choice .... People's census.

need to survive has overwhelmed the With a high density of city-owned

goodness people have." housing, the area has a double-edged

For the staff at Rheedlen, the genesis connection to the city's shelter system

of Community Pride was in the lessons for homeless families. Most families

they learned from another of their pro- seeking shelter come from neighbor-

jects, Neighborhood Gold, which pro- hoods like this one, studies show, and

vides comprehensive support services the nature of housing here appears to be

and case management for families mov- a large part of the reason why: a 1993

ing from homeless shelters into apart- report by Anna Lou Dehavenon of the

ments in Central Harlem. The group Action Research Project on Hunger,

quickly found that services were only a Homelessness and Family Health found

small part of what they had to do. that one-third of all families seeking

"We realized you couldn't save fami- shelter came from city-owned buildings,

lies without dealing with housing primarily because of intolerable physical

issues, and the real stuff that made fam- conditions or drug activity. City-owned

ilies stronger was what was happening housing is also one of the few resources

in the community," Canada recalls. ~ the city has for placing homeless families

Neighborhood Gold began to organize a: in permanent apartments. Well over half

tenants in city-owned buildings where i'i: the families in city-owned buildings

o

most formerly homeless families lived, ~ today moved there directly from the

helping them drive out drug dealers <!l shelter system, according to HPD.

and advocate for repairs (see City limits, Geoff Canada, president of the Rheedlen In 1991, when HPD came up with fed-

April 1993). Centers for Children and Families eral funding under the McKinney Act to

It was clear, Canada says, that community organizing was prevent homelessness by improving services to tenants in city-

the single most effective tool for overcoming instability in owned buildings, Rheedlen won a multiyear, annual contract

any given neighborhood: developing people's strengths as of $200,000 to do the work in Central Harlem. Soon after,

well as their desire and ability to change things, and thus Community Pride set up shop in a brownstone on West 122nd

countering the ravages of poverty. "Sometimes when you look Street and raised another $150,000 from the Edna McConnell

at problems, you come up with solutions based on mental Clark Foundation for organizing and other work.

health issues, drug issues, racial issues, when the real issue is Many of the people they try to help don't live on West

mostly poverty," says Canada. "While you might have to 119th Street. By contract, the organization provides ser-

come in on the short term and deal with the symptoms that vices to tenants throughout the southern part of Central

poverty produces, the only real cure is changing the nature of Harlem. Much of their work involves arranging for home care

l8IDECEMBER 1994/CITY LIMITS

The idea is not to

flood the community

with social services,

but to provide

the resources that

neighborhoods like

this have not been

able to afford

of their own accord.

attendants or health

services for elderly

people, or advocat-

ing for apartment

repairs from the city.

But there are far

more difficult cases

as well, such as

helping a mother

cope with her 13-

and 14-year-old

children who have

become addicted to

drugs, or working

with an older man

who has strong lead-

ership skills but

needs to kick an

alcohol habit.

In the last year,

seven youths with

ties to Community

Pride have suffered

violent deaths on

Harlem streets. When

one young man was

Lee Farrow. director of Community Pride shot dead on the

block last year, his

mother, who lived near the spot where it happened, could no

longer face the horrible patch of sidewalk. Community Pride

helped her move away from the area, rebuild her life and care

for her other young children.

It can be extraordinarily difficult work, says social worker

Leslie Sims, but it is more "real" than many social workers

ever get to experience. "When you finish a case, it can be so

fulfilling. You can believe in what you are doing."

The idea, adds Farrow, is not to flood the community

with social services, but to provide the resources that neigh-

borhoods like this have not been able to afford of their own

accord.

"We don't need social services any more than anyone

else," suggests Janice Dozier, a choreographer who is secre-

tary of the tenant association at 8 West 119th Street and

who has been working with Community Pride to pull the

block together. "What we need is organization. People

downtown have advocates who know what's available.

They band together and spend money and scream for what

they want. Uptown, they don't know. When you approach

institutions they push you aside."

P

art of Community Pride's organizing strategy has

been to build trust with the neighborhood

through its youth programs and to build a sense

of community through celebrations. After school

and in the evening, the two-story office on West