Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Lib Ya

Încărcat de

Sidharth AnejaDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Lib Ya

Încărcat de

Sidharth AnejaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The 2011 Libyan civil war[38] (also referred to as the Libyan revolution[39]) was an armed conflict in the North

African state of Libya, fought between forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and those seeking to oust his government.[40][41] The war was preceded by protests in Benghazi beginning on 15 February 2011, which led to clashes with security forces that fired upon the crowd.[42] The protests escalated into an uprising that spread across the country, with the forces opposing Gaddafi establishing an interim governing body, the National Transitional Council, the stated goal of which was to overthrow Gaddafi and hold democratic elections.[43] On 16 September 2011, the National Transitional Council was recognised by the United Nations as the legal representative of Libya, replacing Gaddafi's government. The United Nations Security Council passed an initial resolution on 26 February, freezing the assets of Gaddafi and his inner circle and restricting their travel, and referred the matter to the International Criminal Court for investigation.[44] In early March, Gaddafi's forces rallied, pushed eastwards and re-took several coastal cities before attacking Benghazi. A further U.N. resolution authorised member states to establish and enforce a no-fly zone over Libya.[45] The Gaddafi government then announced a ceasefire, but failed to uphold it.[46] In August, rebel forces engaged in a coastal offensive and took most of their lost territory, and captured the capital city of Tripoli,[47] while Gaddafi evaded capture and loyalists engaged in a rearguard campaign.[48] Muammar Gaddafi remained at large until 20 October 2011, when he was captured and killed attempting to escape from Sirte.[49] The National Transitional Council declared the liberation of Libya and the official end of the war on 23 October 2011 Background Leadership Muammar Gaddafi was the de-facto ruler of Libya since he led a military coup that overthrew King Idris I in 1969.[51] He abolished the Libyan Constitution of 1951, and adopted laws based on his own ideology outlined in his manifesto The Green Book. He officially stepped down from power in 1977, but continued to hold a symbolic role within the country's governance until 2011.[52][53] Under Gaddafi, Libya was theoretically a decentralized, direct democracy[54] state run according to the philosophy of Gaddafi's The Green Book, with Gaddafi retaining a ceremonial position. Libya was officially run by a system of people's committees which served as local governments for the country's subdivisions, an indirectly-elected General People's Congress as the legislature, and the General People's Committee, led by a Secretary-General, as the executive branch. According to Freedom House, however, these structures were often manipulated to ensure the dominance of Gaddafi, who allegedly continued to dominate all aspects of government, and the country's political system was widely seen as a rubber-stamp.[55] WikiLeaks' disclosure of confidential US diplomatic cables revealed US diplomats there speaking of Gaddafi's "mastery of tactical manoeuvring".[56] While placing relatives and loyal members of his tribe in central military and government positions, he skillfully marginalized supporters and rivals, thus maintaining a delicate balance of powers, stability and economic developments. This extended even to his own sons, as he repeatedly changed affections to avoid the rise of a clear successor and rival.[56] According to several Western media sources, Gaddafi feared a military coup against his government and deliberately kept Libya's military relatively weak. The Libyan Army consisted of about 50,000 personnel. Its most powerful units were four crack brigades of highly equipped and trained soldiers, composed of members of Gaddafi's tribe or members of other tribes loyal to him. One, the Khamis Brigade, was led by his son Khamis. Local militias and Revolutionary Committees across the country were also kept well-armed. By contrast, regular military units were poorly armed and trained, and were armed with largely outdated military equipment.[57][58][59]

According to Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, however, the reason for the country's de-militarization was a reaction to the Iraq War, so that Libya wouldn't be accused of possessing Weapon of mass destruction (WMDs) and face the same fate. He also accused NATO of betraying their trust and taking advantage of this weakness to launch an air attack, recommending other nations to build up their military defences in order to prevent facing the same fate as Libya.[60] Development and corruption A large share of the business enterprise was allegedly controlled by Gaddafi and his family.[61] A leaked diplomatic cable described Libyan economy as "a kleptocracy in which the government either the al-Gaddafi family itself or its close political allies has a direct stake in anything worth buying, selling or owning".[62] Gaddafi amassed a vast personal fortune during his 42-year leadership.[63] Much of the state's income came from its oil production, which soared in the 1970s, and was spent on arms purchases and on sponsoring violence around the world.[64][65] Gaddafi's relatives adopted lavish lifestyles, including luxurious homes, Hollywood film investments, and private parties with American pop stars.[62][66] Petroleum revenues contributed up to 58% of Libya's GDP.[67] Governments with resource curse revenue have a lower need for taxes from other industries and consequently feel less pressure to develop their middle class. To calm down opposition, they can use the income from natural resources to offer services to the population, or to specific government supporters.[68] Libya's oil wealth being spread over a relatively small population gave it a higher GDP per capita than in neighbouring states, similar to in Equatorial Guinea.[69][70][71] Libya's GDP per capita (PPP), human development index, and literacy rate were better than in Egypt and Tunisia, whose revolutions preceded the outbreak of protests in Libya.[72] Libya's corruption perception index in 2010 was 2.2, ranking 146th out of 178 countries, which was worse than that of Egypt (rank 98th) and Tunisia (rank 59th), two neighbouring states that had uprisings preceding Libya's.[73] One paper speculated that such a situation creates a wider contrast between good education, high demand for democracy, and the government's practices (perceived corruption, political system, supply of democracy).[72] Gaddafi was planning to combat corruption in the state by introducing reforms where oil profits are handed out directly to citizens rather than to government bodies, stating that "as long as money is administered by a government body, there would be theft and corruption."[74] An estimated 20.74% of Libyan citizens were unemployed, and about one-third lived below the national poverty line. More than 16% of families had none of its members earning a stable income, while 43.3% had just one. Despite one of the highest unemployment rates in the region, there was a consistent labor shortage with over a million migrant workers present on the market. [75] These migrant workers formed the bulk of the refugees leaving Libya after the beginning of hostilities. Despite this, Libya's Human Development Index in 2010 was the highest in Africa and greater than that of Saudi Arabia. Libya had welfare systems allowing access to free education, free healthcare, and financial assistance for housing, while the Great Manmade River was built to allow free access to fresh water across large parts of the country.[76] Some of the worst economic conditions were in the eastern parts of the state, once a breadbasket of the ancient world, where Gaddafi extracted oil.[77][78] Despite improvements in housing and the Great Manmade River allowing access to free fresh water,[76] not much infrastructure beyond this was developed in the region for many years, with the only sewage facility in Benghazi being over 40 years old, and untreated sewage has resulted in environmental problems.[79] Despite Gaddafi's government offering free healthcare to all citizens,[76] the medical system was seen as poor and had become an infuriating symbol of the spotty distribution of resources in the country. The apparent lack of decent medical care often led Libyans to seek medical care in neighboring countries such as Tunisia and Egypt.[80] The civil war was viewed as part of the Arab Spring, which had already resulted in the ousting of

long-term presidents of adjacent Tunisia and Egypt, with the initial protests all using similar slogans.[81] Social media played an important role in organizing the opposition.[82] Human rights and violations in Libya Further information: Human rights in Libya According to the 2009 Freedom of the Press Index, Libya is the most-censored state in the Middle East and North Africa.[83] Gaddafi allegedly created Revolutionary committees to keep tight control over internal dissent in 1973. Ten to 20 percent of Libyans worked as informants for these committees. Surveillance took place in the government, in factories, and in the education sector.[84] The government often executed dissidents through public hangings and mutilations and rebroadcast them on state television channels.[84][85] In 2011, Libya's press was rated as the most censored in the Middle East and North Africa.[86] Up to the mid 1980s, Libya's intelligence service conducted assassinations of Libyan dissidents around the world.[84][87] As late as 2004, Gaddafi still provided bounties on his critics, including $1 million for one Libyan journalist in the United Kingdom.[88] Until recently, foreign languages such as English and French were banned from school syllabus and talking with foreigners about politics carried a three-year prison term.[89] Dissent was illegal under Law 75 of 1973, and Gaddafi regularly asserted that anyone guilty of founding a political party would be executed.[84] Uprising and civil war Main article: Timeline of the 2011 Libyan civil war before intervention A girl in Benghazi with a placard saying that the Libyan tribes are united, on 23 February 2011 The protests, unrest and confrontations began in earnest on 15 February 2011. On the evening of 15 February, between 500 and 600 demonstrators protested in front of Benghazi's police headquarters after the arrest of human rights lawyer Fathi Terbil. The protest was broken up violently by police, resulting in clashes in which 38 people were injured, among them ten security personnel.[99][100] The novelist Idris Al-Mesmari was arrested hours after giving an interview with Al Jazeera about the police reaction to protests.[99] In Bayda and Zintan, hundreds of protesters in each town called for an end of the Gaddafi government and set fire to police and security buildings.[99] In Zintan, the protesters set up tents in the town centre.[99] The armed protests continued the following day in Benghazi, Derna and Bayda. Libyan security forces allegedly responded with lethal force. Hundreds gathered at Maydan al-Shajara in Benghazi, and authorities tried to disperse protesters with water cannons.[101] The Libyan National Transitional Council flag is flown from a communications tower in Bayda in July. A "Day of Rage" in Libya and by Libyans in exile was planned for 17 February.[98][102][103] The National Conference for the Libyan Opposition asked that all groups opposed to the Gaddafi government protest on 17 February, in memory of demonstrations in Benghazi five years earlier. [98] The plans to protest were inspired by the Tunisian and Egyptian revolution.[98] Protests took place in Benghazi, Ajdabiya, Derna, Zintan, and Bayda. Libyan security forces fired live ammunition into the armed protests. Protesters torched a number of government buildings, including a police station.[104][105] In Tripoli, protesters managed to burn security buildings and the People's Hall. According to a report from the International Crisis Group, "much Western media coverage has from the outset presented a very one-sided view of the logic of events, portraying the protest movement as entirely peaceful and repeatedly suggesting that the government's security forces were unaccountably massacring unarmed demonstrators who presented no security challenge".[106] On 18 February, police and army personnel later withdrew from Benghazi after being overwhelmed by protesters. Some army personnel also joined the protesters; they then seized the local radio station. In Bayda, unconfirmed reports indicated that the local police force and riotcontrol units joined the protesters.[107] On 19 February, witnesses in Libya reported helicopters

firing into crowds of anti-government protesters.[108] The army withdrew from the city of Bayda. Cultural revolt Al-Soo'al (The Question)[109] Muammar: You have never served the people Muammar: You'd better give up Confess. You cannot escape Our revenge will catch you As a train roars through a wall We will drown you. Rap, hip hop and traditional music, beside other genres, have played a role in encouraging the dissidents to Gaddafi's government. Music has been controlled and dissenting cultural figures have been arrested or tortured in Arab Spring countries, including Libya.[109] The music has provided an important platform by means of communication amongst the demonstrators. The music has helped create moral support and encouraged a spirit of resistance and revolt against the governments.[109] An anonymous hip hop artist called Ibn Thabit has given a voice to "disenfranchised Libyans looking for a nonviolent way to express their political will".[110][111] On his website, Ibn Thabit claims that has been attacking Gaddafi with his music since 2008 when he posted his first song on the internet, titled "Moammar the coward".[110][112] Lyrics of a song Al-Soo'al released by Ibn Thabit on YouTube on 27 January 2011, weeks before the riots began in Libya are indicative of the rebel sentiment.[109] Some groups, such as a rock band from Benghazi called the "Guys Underground", used metaphors to cloak the censure of the authorities. The group released a song just before the uprising entitled Like My Father Always Says to ridicule an autocratic fictional male head of a family which was a veiled reference to Colonel Gaddafi.[109] Organization 2011 Libyan uprising Voice of America.ogv Libyan Boy Scouts helping in the social services in Benghazi. See also: National Transitional Council Many opposition participants have called for a return to the 1952 constitution and a transition to multi-party democracy. Military units who have joined the rebellion and many volunteers have formed an army to defend against Jamahiriya attacks and to work to bring Tripoli under the influence of Jalil.[113] In Tobruk, volunteers turned a former headquarters of the government into a centre for helping protesters. Volunteers reportedly guard the port, local banks and oil terminals to keep the oil flowing. Teachers and engineers have set up a committee to collect weapons.[78] Likewise supply lines were run by volunteers. For example, in Misrata people organized a pizza service which delivered up to 8,000 pizzas a day to fighters.[114] The National Transitional Council (Arabic: ) was established on 27 February in an effort to consolidate efforts for change in the rule of Libya.[115] The main objectives of the group did not include forming an interim government, but instead to coordinate resistance efforts between the different towns held in rebel control, and to give a political "face" to the opposition to present to the world.[116] The Benghazi-based opposition government has called for a no-fly zone and airstrikes against the Jamahiriya.[117] The council refers to the Libyan state as the Libyan Republic and it now has a website.[118] Former Jamahiriya Justice Minister Mustafa Abdel Jalil said in February that the new government will prepare for elections and they could be held in three months.[119] On 29 March, the political and international affairs committee of the Council presented its eight-point plan for Libya in The Guardian newspaper, stating they would hold free and fair elections and draft a national constitution.[40][41]

An independent newspaper called Libya appeared in Benghazi, as well as rebel-controlled radio stations.[120] Some of the rebels oppose tribalism and wear vests bearing slogans such as "No to tribalism, no to factionalism".[78] Libyans have said that they have found abandoned torture chambers and devices that have been used in the past.[121] Composition of rebel forces The rebels are composed primarily of civilians, such as teachers, students, lawyers, and oil workers, and a contingent of professional soldiers that defected from the Libyan Army and joined the rebels.[122] The Islamist group Libyan Islamic Fighting Group is considered part of the rebel movement,[123] as is the Obaida Ibn Jarrah Brigade which has been held responsible for the assassination of top rebel commander Gen Abdel Fattah Younes.[124] Gaddafi's administration had repeatedly asserted that the rebels included al-Qaeda fighters.[125] NATO's Supreme Allied Commander James G. Stavridis stated that intelligence reports suggested "flickers" of al-Qaeda activity were present among the rebels, but also added that there is not sufficient information to confirm there is any significant al-Qaeda or terrorist presence.[126][127] Denials of al-Qaeda membership were issued by the rebels.[128] State response Further information: Muammar Gaddafi's response to the 2011 Libyan civil war Gaddafi dismissed his opponents as being influenced by hallucinogenic drugs put in drinks and pills. He specifically referred to substances in milk, coffee and Nescaf. Gaddafi claimed Bin Laden and Al-Qaeda were distributing these hallucinogenic drugs. He also blamed alcohol.[129] [130][131] Gaddafi later also claimed that the revolt against his rule was the result of a colonialist plot by foreign states, particularly blaming France, the US and the UK, to control oil and enslave the Libyan people. He referred to the rebels as "cockroaches" and "rats", and vowed not to step down and to cleanse Libya house by house until the insurrection was crushed.[132][133][134] [135][136] Gaddafi declared that people who don't "love" him "do not deserve to live".[133][135] He called himself a "warrior", and vowed to fight on and die a "martyr", and urged his supporters to leave their homes and attack rebels "in their lairs". Gaddafi claimed that he had not yet ordered the use of force, and threatened that "everything will burn" when he did. Responding to demands that he step down, he claimed that he could not step down, as he held a purely symbolic position like Queen Elizabeth, and that the people were in power.[137] The Swedish peace research institute SIPRI reported flights between Tripoli and a dedicated military base in Belarus which only handles stockpiled weaponry and military equipment.[138] Violence The Libyan government were reported to have employed snipers, artillery, helicopter gunships, warplanes, anti-aircraft weaponry, and warships against demonstrations and funeral processions. [139] It was also reported that security forces and foreign mercenaries repeatedly used firearms, including assault rifles and machine guns, as well as knives against protesters. Amnesty International initially reported that writers, intellectuals and other prominent opposition sympathizers disappeared during the early days of the conflict in Gaddafi-controlled cities, and that they may have been subjected to torture or execution.[140] Rebel fighter in hospital in Tripoli Amnesty International also reported that security forces targeted paramedics helping injured protesters.[141] In multiple incidents, Gaddafi's forces were documented using ambulances in their attacks.[142][143] Injured demonstrators were sometimes denied access to hospitals and ambulance transport. The government also banned giving blood transfusions to people who had taken part in the demonstrations.[144] Security forces, including members of Gaddafi's Revolutionary Committees, stormed hospitals and removed the dead. Injured protesters were either summarily executed or had their oxygen masks, IV drips, and wires connected to the monitors removed. The dead and injured were piled into vehicles and taken away, possibly for

cremation.[145][146] Doctors were prevented from documenting the numbers of dead and wounded, but an orderly in a Tripoli hospital morgue estimated to the BBC that 600700 protesters were killed in Green Square in Tripoli on 20 February. The orderly claimed that ambulances brought in three or four corpses at a time, and that after the ice lockers were filled to capacity, bodies were placed on stretchers or the floor, and that "it was in the same at the other hospitals".[145] International Criminal Court chief prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo estimated that 500700 people were killed by security forces in February 2011, before the rebels took up arms. According to Moreno-Ocampo, "shooting at protesters was systematic".[147] Gaddafi suppressed protests in Tripoli by distributing automobiles, money and weapons for hired followers to drive around Tripoli and attack people showing signs of dissent.[148][149] In Tripoli, "death squads" of mercenaries and Revolutionary Committees members patrolled the streets, and shot people who tried to take the dead off the streets or gather in groups.[150] The International Federation for Human Rights concluded that Gaddafi is implementing a strategy of scorched earth. The organization stated that "It is reasonable to fear that he has, in fact, decided to largely eliminate, wherever he still can, Libyan citizens who stood up against his regime and furthermore, to systematically and indiscriminately repress civilians. These acts can be characterized as crimes against humanity, as defined in Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court."[151] Gaddafi reportedly continued these tactics when the protests escalated into an armed conflict. During the siege of Misrata, Amnesty International reported "horrifying" tactics such as "indiscriminate attacks that have led to massive civilian casualties, including use of heavy artillery, rockets and cluster bombs in civilian areas and sniper fire against residents."[152] Gaddafi's military commanders also reportedly executed soldiers who refused to fire on protesters.[153] The International Federation for Human Rights reported a case where 130 soldiers were executed.[154] Some of the soldiers executed by their commanders were burned alive.[155] In June 2011, a more detailed investigation carried out by Amnesty International found that many of the allegations against Gaddafi and the Libyan state turned out to either be false or lack any credible evidence, noting that rebels at times appeared to have knowingly made false claims or manufactured evidence. According to the Amnesty investigation, the number of casualties was heavily exaggerated, some of the protesters may have been armed, "there is no proof of mass killing of civilians on the scale of Syria or Yemen," there is no evidence that aircraft or heavy antiaircraft machine guns were used against crowds, and there is no evidence of African mercenaries being used, which it described as a "myth" that led to lynchings and executions of black people by rebel forces. It criticized "Western media coverage" which "has from the outset presented a very one-sided view of the logic of events, portraying the protest movement as entirely peaceful and repeatedly suggesting that the regime's security forces were unaccountably massacring unarmed demonstrators who presented no security challenge."[42] Humanitarian situation Main article: Humanitarian situation during the 2011 Libyan civil war By the end of February 2011, supplies of medicine, fuel and food were dangerously low in Libya's urban centres.[241] On 25 February, the International Committee of the Red Cross launched an emergency appeal for US$6.4 million to meet the emergency needs of people affected by the violent unrest in Libya.[242] In early March, the fighting across Libya meant that more than a million people fleeing or inside the country needed humanitarian aid.[243][244] The Islamic Relief and the WFP also coordinated a shipment of humanitarian supplies to Misrata.[245] In March, the Swedish government donated medical supplies and other humanitarian aid and the UN World

Food Programme provided food. Turkey sent a hospital ship to Misrata and a Turkish cargo ship brought 141 tons of humanitarian aid.[245][246] Another humanitarian issue was refugees fleeing the crisis. A humanitarian ship docked in harbour of Misrata in April to begin the evacuation of stranded migrants.[247] By 10 July, over 150,000 migrants were evacutated.[248] Migrants were also stranded elsewhere in Libya, such as in the southern towns of Sebha and Gatroum. Fleeing the violence of Tripoli by road, as many as 4,000 refugees were crossing the LibyaTunisia border daily during the first days of the uprising. Among those escaping the violence were native Libyans as well as foreign nationals including Egyptians, Tunisians and Turks.[24 International reactions Main articles: International reactions to the 2011 Libyan civil war and US domestic reactions to the 2011 military intervention in Libya A total of 19 charter flights evacuated Chinese citizens from Libya via Malta.[299] Here a chartered China Eastern Airlines Airbus A340 is seen at Malta International Airport on 26 February 2011. Many states and supranational bodies condemned Gaddafi's government over its attacks on civilian targets within the country. Virtually all Western countries cut off diplomatic relations with Gaddafi's government over an aerial bombing campaign in February and March, and a number of other countries led by Peru and Botswana did likewise. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970 was adopted on 26 February, freezing the assets of Gaddafi and ten members of his inner circle and restricting their travel. The resolution also referred the actions of the government to the International Criminal Court for investigation,[44] and an arrest warrant for Gaddafi was issued on 27 June.[300] This was followed by an arrest warrant issued by Interpol on 8 September.[301] The government's use of the Libyan Air Force to strike civilians led to the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973 to create a Libyan no-fly zone on 17 March, though several countries involved in the resolution's enforcement have also carried out regular strike missions to degrade the offensive capacity of the Libyan Army and destroy the government's command and control capabilities, effectively acting in de facto support of anti-Gaddafi forces on the ground. 100 countries have recognized the anti-Gaddafi National Transitional Council as Libya's legitimate representative, with many of those countries explicitly describing it as the legal interim government of the country due to the perceived loss of legitimacy on the part of Gaddafi's government. Many states have also either issued travel advisories or attempted evacuations. Some evacuations were successful in either going to Malta or via land borders to Egypt or Tunisia; other attempts were hindered by tarmac damage at Benghazi's airport or refusals of permission to land in Tripoli. There were also several solidarity protests in other countries that were mostly composed of Libyan expatriates. Financial markets around the world had adverse reactions to the instability with oil prices rising to a two-and-a-half year high Date 15 February 23 October 2011 (8 months, 8 days) Location Libya Result Overthrow of Gaddafi government Anti-Gaddafi forces take control of all major Libyan cities.[1] Muammar Gaddafi is killed.[2] The National Transitional Council assumes interim control of Libya. 100 countries, UN, EU and AU diplomatically recognise the National Transitional Council as the sole governing authority for Libya.

Domestic reactions Prime Minister Mahmoud Jibril said he wished Gaddafi had remained alive so he could be tried for crimes against humanity,[35] saying he had wanted to serve as Gaddafi's prosecutor,[55] but now that he was dead, Libya would need a meticulous plan for the transition to democracy.[56] Chairman Mustafa Abdul Jalil, the de facto head of state, said, "Our forces' resistance to Gaddafi ended well, with the help of God." He declared Libya to be "liberated" at a ceremony in Benghazi on 23 October, three days after Gaddafi's death.[53] NTC official Ali Tarhouni said on 22 October that he had instructed the military council in Misrata to keep Gaddafi's body preserved for several days in a commercial freezer "to make sure that everybody knows he is dead".[57] Two days later, Tarhouni acknowledged that there had been human rights abuses in the Battle of Sirte, which he said the NTC condemned, and said the Executive Board "did not want to put an end to that tyrant's life before bringing him to trial and making him answer questions that have always haunted Libyans".[58] A spokesman for the Misrata military council, Fathi Bashagha, said the council was confident Gaddafi was dead and that he had died of wounds sustained during fighting before his capture. [59] Saadi Gaddafi, one of Muammar Gaddafi's surviving sons in exile in Niger, said through an attorney that he was "shocked and outraged by vicious brutality" toward his father and his brother, Moatassem Gaddafi, and that the killing showed that the new Libyan leadership could not be trusted to hold fair trials.[60] [edit] International reactions Main article: International reactions to the death of Muammar Gaddafi See also: International reactions to the 2011 military intervention in Libya Many leaders and foreign ministers of European countries, as well as fellow Western countries including Australia, Canada, and the United States, made statements hailing Gaddafi's death as a positive development for Libya. The city-state of Vatican City responded to the event by declaring it recognised the National Transitional Council as Libya's legitimate government.[61] World leaders such as Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi[62] and Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard[63] suggested that the death of Gaddafi meant the war was over. Some officials, such as UK Foreign Secretary William Hague, expressed disappointment that Gaddafi was not brought back alive and made to stand trial.[64] Reaction from the governments of countries closely allied with Gaddafi's Libya was negative, with Venezuelan President Hugo Chvez describing the former Libyan leader's death as an assassination and an "outrage".[65] [edit] NATO See also: International reactions to the death of Muammar Gaddafi - NATO Immediately after Gaddafi's death, NATO released a statement denying it knew beforehand that Gaddafi was traveling in the convoy it struck.[10] Admiral James G. Stavridis, NATO's top officer, said the death of Gaddafi meant that NATO would likely wind down its operations in Libya.[66] Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the NATO secretary-general, said NATO would "terminate [its] mission in coordination with the United Nations and the National Transitional Council" Death of Muammar Gaddafi Muammar Gaddafi was killed in his home town of Sirte.

Muammar Gaddafi, leader of Libya for 42 years from 1969 to 2011, died on 20 October 2011 during the 2011 Libyan civil war. Gaddafi was captured alive after his convoy was attacked by NATO warplanes as Sirte fell on 20 October 2011. Gadaffi was then beaten and killed by the rebels.[2]

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- FarmersAssociation Constitution&Bylaws EnglishDocument10 paginiFarmersAssociation Constitution&Bylaws EnglishGelberNavarra100% (1)

- Whatever Happened To MarShawn DeMurDocument6 paginiWhatever Happened To MarShawn DeMurCarlos Adolfo Bermudez Sebastiani100% (1)

- Mortgage Dollar Rolls DefinedDocument4 paginiMortgage Dollar Rolls DefinedSidharth AnejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To Cost Accounting: Prof. Abhay KumarDocument32 paginiIntroduction To Cost Accounting: Prof. Abhay KumarSidharth AnejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FI+Analyst+Insights TBA 2014 FINALDocument4 paginiFI+Analyst+Insights TBA 2014 FINALSidharth AnejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RM AbstractDocument1 paginăRM AbstractSidharth AnejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- MergerDocument3 paginiMergerSidharth AnejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- σdDocument1 paginăσdSidharth AnejaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ntlo Ya Dikgosi: BotswanaDocument2 paginiNtlo Ya Dikgosi: BotswanaLaeh SaclagÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRIM 2 Philippine Criminal Justice System PDFDocument1 paginăCRIM 2 Philippine Criminal Justice System PDFRaymundÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education, Social Structure, Social Stratification and Social Mobility PDFDocument14 paginiEducation, Social Structure, Social Stratification and Social Mobility PDFNitika SinglaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Change Name Procedure Central GovtDocument4 paginiChange Name Procedure Central GovtbabakababaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2023 Barangay and SK ElectionsDocument1 pagină2023 Barangay and SK ElectionsAbdul Adziz KundaraanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judge ScriptDocument2 paginiJudge ScriptEngHui EuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salient Features of The Revised Guidelines For Continuous Trial of Criminal CasesDocument3 paginiSalient Features of The Revised Guidelines For Continuous Trial of Criminal CasessujeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Educational Language Policy in Spain and Its Complex Social ImplicationsDocument4 paginiEducational Language Policy in Spain and Its Complex Social ImplicationsIjahss JournalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument16 paginiCorporate Social ResponsibilityDebanjan BhattacharyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ResolutionDocument2 paginiResolutionnesonnimÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Public Health ModelDocument7 paginiThe Public Health ModelJay Thomas Taber100% (1)

- Theoriesofmigration 2Document1 paginăTheoriesofmigration 2naughty dela cruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Annex H For BarangayDocument1 paginăAnnex H For BarangaySagud Bahley Brgy CouncilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson 2: Interrogating GlobalizationDocument19 paginiLesson 2: Interrogating GlobalizationRei Ian G. CabeguinÎncă nu există evaluări

- PHILIPPINE CARPET MANUFACTURING CORPORATION vs. TAGYAMONDocument2 paginiPHILIPPINE CARPET MANUFACTURING CORPORATION vs. TAGYAMONCharles Roger RayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 2 Xgoodgov Ballada 2Document23 paginiChapter 2 Xgoodgov Ballada 2Richie RayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calida Petition Vs Senate ProbeDocument39 paginiCalida Petition Vs Senate ProbeNami Buan100% (1)

- Law - Legal Forms - Entry of Appearance - of Law StudentDocument9 paginiLaw - Legal Forms - Entry of Appearance - of Law StudentNardz AndananÎncă nu există evaluări

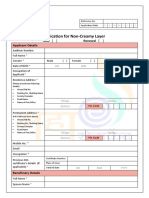

- Application For Non-Creamy Layer Certificate v0.1 PDFDocument4 paginiApplication For Non-Creamy Layer Certificate v0.1 PDFsameer100% (1)

- Role of Juvenile Justice System in IndiaDocument11 paginiRole of Juvenile Justice System in IndiaANADI SONIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 1 UCSPDocument99 paginiWeek 1 UCSPJuztine ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summary of Judgment in Bhutto CaseDocument19 paginiSummary of Judgment in Bhutto CaseNadeem Latif Khan100% (1)

- Class X - History-Chapter 8-The Cripps Mission and The Quit India MovementDocument11 paginiClass X - History-Chapter 8-The Cripps Mission and The Quit India MovementGraciously meÎncă nu există evaluări

- IntroductionDocument2 paginiIntroductionMaya Caballo ReuterÎncă nu există evaluări

- A&F Case StudyDocument8 paginiA&F Case StudyLiladhar PatilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Petition For Appeal: Bickerstaff CaseDocument12 paginiPetition For Appeal: Bickerstaff CasesaukvalleynewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adventure Academy Inc Waitlist PolicyDocument2 paginiAdventure Academy Inc Waitlist Policyapi-466796987Încă nu există evaluări

- Transfer of Civil SuitsDocument10 paginiTransfer of Civil SuitsChinmoy MishraÎncă nu există evaluări