Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India

Încărcat de

chandu521Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India

Încărcat de

chandu521Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

PART IV:

Case Studies

1. Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India: The Battle of the Bottle Continues, 395 2. Arun Ice Cream, 409 3. Gujarat Co-Operative Milk Marketing Federation Limited (GCMMF), 421 4. The Park, Calcutta, 439 5. Kanpur Confectioneries Private Limited (A), 461 6. Kanpur Confectioneries Private Limited (B), 467 7. Aravind Eye Care System: Giving the Most Precious Gift, 473 8. ITC Limited, Bangalore (A), 495 9. ITC Limited, Bangalore (B), 499 10. TheLivingRoom:RedefiningtheFurnitureIndustry, 505 11. Cognizant: Preparing for a Global Footprint, 515 12. One Mission, Multiple Roads: Aravind Eye Care System in 2009, 535 13. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (WMT), 555 14. Alibaba.com, 583 15. Apple Computer, Inc.: Maintaining the Music Business While Introducing iPhone and Apple TV, 597 16. Blockbuster Acquires Movielink: A Growth Strategy?, 615 17. A Horror Show at the Cinemaplex?, 627 18. JetBlue Airways: Challenges Ahead, 635 19. Blue Ocean Strategy at Henkel, 655 20. Nucor in 2009, 663 21. TNK-BP (Russia) 2008, 687 22. Barclays: Matt Barretts JourneyWinning Hearts and Minds, 701 23. Nintendos Disruptive Strategy: Implications for the Video Game Industry, 707

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India: The Battle of the Bottle Continues

Case

S. Manikutty

Soft drinks or cool drinks, as they are known in India, refer to non-alcoholic drinks served in bottles or other packaging, to be distinguished from hot beverages such as coffee and tea, or cold beverages such as squashes and freshlemonsyrupsorsyrupsof differentflavorsmixed withwater.Softdrinksconsistof aflavorbase,asweetener, and carbonated water. These drinks were generally not very popular in India in the 1950s and early 1960s. At homes, fresh juices and squashes were more popular, whileteaorcoffeewereusuallyservedinofficesduring meetings. Most of the bottled soft drinks at that time were local brands, packaged in semi-automatic and handoperated plants. share the secret behind the concentrate, enabling its local manufacture. Both these conditions were unacceptable to Coca-Cola. Hence it withdrew from India in 1977. The field thereafter was left wide open for Indian soft drinks manufacturers. They exploited this bonanza to the hilt. Parle Industries, led by Ramesh Chauhan, made great headway and captured a market share of more than 60 per cent. The profits derived were very healthy indeed. Parley Industries had a formidable array of brands which became very powerful in the Indian market: Thums Up (cola drink), Gold Spot (orange), Limca (clouded lemon), Citra (clear lemon), Maaza (mango flavoured, non-carbonated soft drinkorNCSD)andFrooti(mangoflavouredNCSDin tetrapacks). Besides Parle, there was Pure Drinks Ltd., owned by Charanjit Singh, which was the main bottler for Coca-Cola before its withdrawal. It launched its own brand,CampaCola,incolaflavorandsomeotherbrands inotherflavorslikeCampaOrange.PureDrinkscaptured about 20 per cent of the soft drinks market in the 1980s, but declined subsequently because of its inability to withstand competition mainly from Parle, and later, Pepsi (which returned to India, see later in the case). Besides Parle and Pure Drinks, there were several other smaller operators such as Dukes and Spencer but they never really made any major inroads into Chauhans empire.

Industry Background

In 1956, Pepsi Co. introduced its aerated soft drinks in India but the efforts in developing the Indian market were not successful. Pepsi withdrew from India in 1961. CocaCola Company then entered India and did much better than Pepsi. Coca-Cola set up a network of franchises and bottling plants across the country. In 1977, with a change in the Central government from the Congress Party, which had ruled India since Independence to the Janata Party, Coca-Cola was asked by the new government to reduce its equity holding to 40 per cent and to

1999 Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. Revised 2001 Cases of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, are prepared as a basis for class discussion. Cases are not designed to present illustrations of either correct or incorrect handling of administrative problems.

396

Strategic Management

The 1980s were a decade of slow liberalization in India. It appeared that time was getting ripe for soft drink multinationals to stage a comeback in the country. ThefirstmovewasmadebyPepsiCoin1986,proposing a tie-up with the Indian firms Punjab Agro Industries Corporation and Voltas Ltd. The proposal included setting up of an agro research centre to develop new varieties of seeds, transfer of the state-of-the-art technology in food and beverage processing and packaging, investment in processing plants for potatoes, grains and vegetables, establishment of facilities for local manufacture of cola and fruit juice concentrates, and substantial export obligations.Againststiff oppositionfromIndianfirms,the proposal was approved, and Pepsi launched its products in January 1991. After quite trying times, especially against Chauhan and with its own partners, Pepsi bought over the equity stakes of Voltas and Punjab Agro, and became a fully owned subsidiary of PepsiCo, USA. Coca-Cola returned to India in 1993. By this time the rules of the game regarding investment by multinationals had changed considerably, and Coca-Cola was allowed entry on terms far easier than those for Pepsi (for example, Coca-Cola was allowed to set up a 100 per cent subsidiary in India without any research or export obligations) although it must be added that, despite the obligations laid down for Pepsi, many of these obligations werenotfulfilledbyPepsiforvariousreasons. The Indian warriors, notably Ramesh Chauhan, attempted many tactics (described by some as street smart) to keep their multinational rivals at bay. But aftera valiantfight,Chauhan soldoutParlessoft drinks brands to Coca-Cola, for a tidy sum of around $40 million, it was believed. By this move, Coca-Cola got a share of about 69 per cent of the soft drinks market, commanded by Parles brands. However, Parle continued in other businesses, as for example, soda and mineral water. It also continued to be a major bottler for Coca-Cola, and was in fact the largest bottler in the country. But in the early years, Coca-Cola and its principal bottler had a relationship far from cosy, with charges and countercharges liberally thrown at each other and made public with great effort. In the opinion of a marketing consultant, For a company like Coke that is so heavily franchise driven, to antagonise its chief bottler was nothing short of suicidal. As a result, Coca-Cola lost one clear year.1 Coca-Cola India also promoted its own brands vigorously, while paying a somewhat step-motherly attention to the ex-Parle brands. This, in the opinion of industry experts, was a major error of judgement. It seemed that Coca-Cola grossly overestimated the power of its own

brands as too well known all over the world, while underestimating the power of the local brands. In the opinion of one of the chief executives of Coca-Cola India, they did not realize that Coca-Cola was a new brand launch, not a relaunch.2 The result of this error of judgement was that the market shares of the Parle brands fell drastically, but these were gained by Pepsi rather than the Coca-Cola brands. Pepsi thus gained a lead in India, one of the few countries in the world where it has led CocaCola consistently. Thus, in 1998, the soft drink market in India was shared by Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and a host of Indian manufacturers, mostly regional brands. The main brands of the major contestants, namely Coca-Cola India and Pepsi India, are shown in Table 1:

Table 1 Brands of CSDs offered by the main players

Flavor Cola Clouded Lime Clear Lime Orange Mango NCSD Soda Coca-Cola Coca-Cola; Thums Up* Fanta; Limca* Citra* Fanta; Gold Spot* Maaza* Kinley Eversel Pepsi Co. Pepsi Cola SevenUp Teem Mirinda

Note: * denotes brands taken over from Parle.

Exactmarketsharefiguresarenotavailable,butitwas speculated that Coca-Cola India (including its ex-Parle brands) had about 55 per cent share of the soft drinks market while Pepsi had nearly 40 per cent. Coca-Cola brand had about 18 per cent; Thums Up about 17 per cent; Pepsi Cola about 27 per cent; Limca about 10 per cent and Teem about 1.5 per cent. Fanta and Mirinda had about 7.9 per cent each.

Products

Soft drinks could be broadly divided into aerated drinks and non-aerated drinks. Aeration was done by mixing carbon dioxide with the base liquid, which in itself was formed by adding water and sugar to the concentrate. The aerated drinks were also known as carbonated soft drinks (CSDs). Non-aerated or non-carbonated soft drinks (NCSDs) were basically diluted fruit pulp, with sugar and preservatives added. Soft drink concentrates were supplied by concentrate producers who possessed the secret formulae which they guarded zealously. The concentrate producers supplied

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India: The Battle of the Bottle Continues

397

these concentrates to bottlers who mixed it with water and sweetener, and carbonated the mixture (for CSDs) by adding carbon dioxide. The production of concentrates involved no high technology or major investment. CSDs in India were largely distributed in returnable glass bottles. This was quite different from the trends in most of the countries across the world, where cans were the dominant mode of packaging. In the 1960s, in USA, glass bottles accounted for 94 per cent of the soft drinks volume, and cans, four per cent. But by 1990, cans accounted for 52 per cent of the market, plastic bottles for 30 per cent, non-returnable glass bottles for 12 per cent, and returnable glass bottles just six per cent. The reason why cans were not popular in India was the price of the drink in canned form, thanks to the high import duties on cans and the high cost of the locally manufactured cans due to poor economies of scale. In India, a bottle (300 ml.) of soft drink cost around `8, while a can of the same drink of the same quantity sold for about `15, the difference being accounted for entirely by the cost of cans. The economies involved in scale can be seen from the fact that, in USA, can manufacture was highly concentrated with fivecompaniesaccountingfor98percentof salesof cans to the soft drinks industry. For can manufacturers, sales of cans to soft drinks manufacturers accounted for about 40 per cent of their sales. Can manufacturing involved setting up of expensive and highly automated lines, with capacities of around 600 to 1200 cans per minute. Another important way of dispensation of CSDs was through fountains, where the concentrate, water, sugar, and carbon dioxide were stored separately and mixed just prior to the purchase and served in glasses. In some cases, the concentrate could be kept in ready mixed form and carbonation done just before the sale. Fountains required special equipment costing around `100,000. An ingenious outlet developed in India was the so called pouring junction, which were metal boxes containing a base of ice which chilled one litre and 1.5 litres bottles and poured out in glasses of 200 ml. at a cost of `5 each. These contraptions cost only about `10,000 and, since they needed no electricity, held great potential in rural areas and roadside shops. NCSDs were served in bottles and in tetrapacks. There were some NCSDs which were sold in concentrate form, requiring the user to mix the concentrate with water prior to consumption. These were available in concentrated liquid and powder form. None of the soft drink manufacturers were involved in this form of selling NCSDs: they were manufactured and sold by companies specializing in this business (e.g. Rasna by Paloma Industries).

The broad breakup of sales between the three kinds of soft drinks in 1998 was as follows. Carbonated Soft Drinks (CSDS) Non-Carbonated Soft Drinks (NCSDs) NCSD concentrates. Liquid, and powder 61.3% 19.5% 10.4%

Squashes and syrups accounted for the rest of the market.

IndIan soft drInks Market

Production in 1996 of CSDs and NCSDs was above 4000 million bottles, or 166 million unit cases or U/Cs3 of value `32 billion. Of this CSDs accounted for nearly 60 per cent and NCSDs for 20 per cent. According to a survey, however, CSDs and NCSDs accounted only for a small percentage of the overall share of throat of those identified as drinkers of soft drinks (i.e. those who had consumed at least once during seven days prior to the survey). The shares of throat of different drinks in India are given in Table 2. Per capita consumption in India of CSDs and NCSDs was still quite low. At about 5 bottles per annum per head, Indias consumption of CSDs and NCSDs was about 1/250 of that of USA, 1/100 of Mexico, 1/23 of that of Thailand, 1/5 of Pakistan, and half of Bangladesh.

Table 2 Shares of throat of different liquids

Liquid Water Tea Coffee Milk CSDs NCSDs Squash/Powders Fresh lime juice (Nimbu pani) Alcohol Share of Throat 75.0 13.3 1.7 4.8 1.8 0.7 0.7 0.9 0.3

However, the market had been showing a good growth of around 12 per cent per annum. It was, however, sensitive to the prices offered by competitors and the climatic pattern: in a year of long, hot summer, sales went up considerably and could be as much as 25 per cent more than in a year of short, relatively cool summer. The soft drink market was quite cyclical, with nearly 40 per cent of sales happening in the four summer months of April to July. A general idea of the cyclical pattern can be seen from Table 3.

398

Strategic Management

ducers also placed orders and negotiated rates for bottles on behalf of the bottlers; they designed the campaigns and promotions, and shared the expenses of advertising Month Index and promotions with the bottlers. They also devised the January 100 quality control systems for the bottlers. February 150 Bottling plants were highly capital intensive. They were March 170 highly automated plants, involving sophisticated machinApril 200 ery(mostlyimported),thetypicalfillingratesbeing600 May 220 to 1200 bottles a minute. Filling lines were interchangeable only for bottles of similar sizes and shapes; thus any June 230 major package changes needed new equipment. A typical July 220 bottling plant cost in India anything between `350 million August 200 and `700 million. Upgradation and modernization were September 170 also expensive, and a common complaint of concentrate October 160 producers was that the bottlers did not have the vision November 150 to invest in upgradation and modernization. Hence, in December 150 the interest of their own sales, concentrate producers assisted manufacturers by sharing the expenditure involved This seasonality had major implications for the way a in modernizing and upgrading the plants. Besides the plant and equipment, bottlers also had CSD company dealt with its suppliers, buyers, and comto invest in bottles, crates, trucks and the cooling equippetition. The soft drink industry had a peculiar supply chain ment in the retailers outlets (vissicoolers and ice boxes). structure, which made it difficult to define its industry These constituted about `100 per crate. Thus, bottling structure. First, there were the owners of the brands of was a business for big guys, and powerful ones at that. soft drinks: The Coca-Cola Company, Pepsi Co., etc. You just cannot talk down to bottlers, in the opinion These companies basically supplied the concentrate and of a marketing consultant in Mumbai, so much so that owned the brands. They also bore a sizeable portion of all the bottlers have direct access to me, said Mr. P.M. 4 promotion, and advertising expenditure. We call them Sinha, Chief Executive of Pepsi in India. There were about 100 bottling companies in India. concentrate manufacturers in this case. The next in the link were bottlers. These bottlers were companies who Coca-Cola (including its ex-Parle brands) had 53 francould be either (i) owned by concentrate manufacturers; chisees and a few company owned bottlers; Pepsi, on the or (ii) franchisees in which case they had the exclusive other hand, had about 15 owned and 11 franchisees. After the bottlers, came the retail outlets in the deright to sell the brands of the concentrate manufacturers within a territory. Since each bottler was allocated livery chain. Many of these retail outlets either sold the a territory, there was no question of any competition finalproductafteropeningthebottles,orsoldthebottles from different bottlers for the same brand. A franchisee to customers who returned them later. There were also bottler could not bottle or market a directly competing non-returnable plastic bottles of 1 and 1.5 litres capacibrand, that is, a Coca-Cola bottler could not bottle or ties. About 15 per cent of consumption of soft drinks market Pepsi Cola. Usually they bottled the entire range was in take-home PET bottles. Larger customers such of a brand owner, but could decline to bottle particu- as restaurants got their supplies directly from the botlar brands. In that case, they could market a competing tling company. There were about 400,000 retail outlets in brand. Thus, a Coca-Cola bottler could refuse to bottle India selling soft drinks. Some of the retail outlets were fountains. Fountains Gold Spot or Fanta and bottle Mirinda. Such instances were considered to be growing faster than bottled drinks, were rare in India, although somewhat common in other mainly because of the lower price at which the drinks countries. Bottlers other than those owned by concentrate pro- could be sold. There were about 4000 fountains vending ducerswereindependentcompanieswhoseprofitorloss Pepsi drinks and 1500 vending Coca-Cola brands. The were their own concern. Concentrate producers supplied larger number of fountains of Pepsi was mainly because the concentrate at an agreed-to price. But the relationship of their earlier entry into the country. Coca-Cola also bewas much more complex than that: the concentrate pro- lieved that quality problems, especially of water, was quite

Table 3 Sale of CSDs and NCSDs in different months during a year (Index: January = 100)

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India: The Battle of the Bottle Continues

399

serious with fountains, and they would like to proceed in a big way only after sorting out this issue. Also, a number of dispensing units were established at petrol pumps. Coca-Cola tied up with Indian Oil Corporation (which had by far the largest number of outlets) while Pepsi had tied up with Bharat Petroleum. In addition to fountains, there were also pouring junctions as mentioned earlier. These were just emerging, however. A crate of soft drinks entered the distribution system at about `100 a crate. The bottlers margins were believed to be about 10 per cent; retailers about 20 per cent; and mark up because of excise and taxes about 40 per cent.

Since PET bottles were coming up as a new trend, suppliers for these needed to be developed. These bottles were also in particular sizes and shapes, with CocaCola having a contour green colored bottle. These bottlesneedtobemadeonlyfromfirstqualityplastic(i.e. not recycled plastic) and with adequate quality control. In 1998, the capacity for these PET bottles was considered to be tight, but it was expected that by 1999, capacity would pose no problem. Sugar was a vital item. Production and movement of sugar from places of production to bottling plants was governed by a maze of complex laws, but what was clear was that the effect was always sub-optimal from the point of view of consumers. The sugar suppliers held suPPlIers complete sway over delivery and prices. Although some For the industry as a whole (i.e. bottlers and brand own- discounts were available for bulk purchase, sizeable bulk ers), there were a number of suppliers whose bargain- purchases were not possible because of regulations. ing power varied a lot. Sugar supply was also not consistent in quality or sweetFirst, there were the manufacturers of bottles. The ness. This led to inconsistency of taste of the product itshape of bottles varied between brands so that the brand self, something the brand owners abhorred. Backward incould be identified from the shape of the bottle itself. tegration into sugar manufacture was not possible at that Coca-Cola had even patented its famous contoured bottle point of time because of licensing restrictions; recently (the hobble skirt shape, as the company called it) all over the policy had been somewhat liberalized, and setting up the world. The bottle manufactures were generally manu- own sugar factories was emerging as a possibility. facturers of glass containers of different kinds, and for Carbon dioxide (CO2) was another important supthem soft drink bottles constituted a significant source ply. There were small and widely dispersed suppliers and of orders. They had to invest in moulds which required each bottler or fountain arranged for its own suppliers. fairly large order sizes, and this constituted some limita- Generally this was not a problem. tion on the variety of bottles that could be introduced Even water was a major problem, since consistency of or the frequency with which they could be changed. The taste was vital. So far the bottlers had tied up with local general rule was that the bottle manufacturers bore the suppliers who supplied water with satisfactory propercost of the moulds, although in some cases the concen- ties. Mineral water was considered a costly option. trate producers and bottlers would contribute a part. Cooling equipment needed were somewhat specialSince sales during the peak season depended very heavily ized and required high degree of reliability. But there on the availability of adequate number of bottles, the were a number of manufacturers of these equipment concentrate producers negotiated the orders on behalf who would supply, install, and maintain them at the venof bottlers for price, delivery, and quantity. They kept dors premises. averyclosetabontheordersplacedsufficientlyinadSoft drinks were essentially driven by brand appeal, vance and in adequate quantity. and hence advertising was extremely vital. Both CocaThe capacity for bottle manufacture was considered Cola and Pepsi had tied up with advertising agencies, and to be adequate in the country, but not generously so. usually for a particular period based on competitive bids. This led to the common practice of pre-empting orders The soft drink manufacturers were quite important to adfor bottles for the season by placing orders that were vertisingagenciesmanyof whomhadsignificantshares somewhat larger than required. In the past, when bottle of their revenues coming from soft drinks advertising: manufacturing capacities were tight, this could cripple one industry source put it at as much as 50 to 60 per thecompetitorwhowouldfindhimself unabletosellbe- cent for some agencies. There were at least 8 to 10 agencause of shortage of bottles. Even at the time of writing cies which were considered suitable from the soft drinks this case, it was vital to place orders for new bottles for manufacturers point of view. Advertising agencies were the coming season well on time; otherwise sales would invariably engaged by the brands and the agencies also suffer in the peak season. planned their campaigns nation-wide.

400

Strategic Management

Event managers and promotion agencies were becoming more important.5 These agencies essentially managed sponsored events or a particular promotion. There were numerous such agencies with quite different capabilities. Research agencies were also important, since it was necessary to continuously monitor market share and preference trends. Since this required at least state-wide operations, these were fairly large. It was the opinion of industry experts that really good quality research agenciesweredifficulttocomeby.

Soft drinks were consumed pronouncedly in urban areas: though only 28 per cent of the population were in urban areas, they accounted for 58 per cent of drinkers and 75 per cent of volume. But of the sales of about 166 million unit cases (U/Cs) in the country, 120 million U/Cs were sold in urban markets; of which 59.3 million U/Cs were sold in four metros alone. Table 4 gives the consumption pattern in terms of geographic spread, while Table 5 showstheconsumerprofileintermsof ageandTable6 showstheconsumerprofileonbasisof income.

Table 4 Soft drink consumption in Indian cities

City Drinkers (million) Volume Per capita (million U/C) (No. of serves p.a.)

Buyers

Buyers, at one level, could be classified as institutional Delhi 7.5 25.0 80 buyers and retail outlets. They eventually sold to final Bombay 7.2 13.4 45 consumers.Thesoftdrinkindustriesclassifiedthefirst Calcutta 5.2 11.6 53 as customers and the latter as consumers. Madras 3.1 9.3 73 Institutional buyers comprised corporations and institutions who bought and stocked soft drinks for servBangalore 2.6 4.3 40 ing visitors, meetings, etc. and hotels and restaurants. Pune 1.4 1.9 34 Compared to retail channels, these were high volume, Total Urban 59.3 114.0 46 Key Markets high image customers. These institutions (including hotels and restaurants) stocked a variety of other soft The age and income profiles of consumers of soft drinks and beverages (tea, coffee, etc.), and hotels and drinks were as follows: restaurants in most states stocked liquors also. Retail outlets stocked for sale to consumers in relaTable 5 Soft drink consumption in terms of age groups tively smaller quantities and depended on turnover. The volume of each was small but collectively, of course, they Age group % of Soft drink Population % consumption accounted for nearly 75 per cent of total business. Hotels and restaurants usually did not display much 1219 years 18 20 promotional material, except perhaps logos, and that too 2029 years 23 33 discretely. They depended on customer pull, i.e. custom3050 years 41 38 ersspecifiedwhichdrinktheypreferred.Theygenerally > 50 years 18 9 didnotmindanybrandinthesameflavor,however.The soft drink manufacturers tried to get exclusive arrange- Source: Data obtained from industry. ments in hotels and restaurants and were moderately Table 6 Soft drink consumption in terms of income successful. Hotels and restaurants were not governed by maximum retail price (MRP) laws and could charge Household % of % of soft % of % of income per population drink volume volume higher than the marked MRP for their ambience. annum (`) drinkers estimate 1 estimate 2 Retail outlets depended heavily on promotional mate>100,000 12 22 25 31 rial, and quite often stocked competing brands. The purchase of soft drinks was generally impulse driven. Retail 50100,000 15 22 23 27 outlets were governed by MRP laws. 2550,000 21 25 23 27 Out of 800 million population in India in the late 1525000 21 17 16 8 1990s, about 150 million could be categorized as con<15,000 30 14 14 7 sumers of soft drinks in the sense that they consumed Notes: 1. Estimate 1 was made by a market research agency while at least one soft drink in one week prior to a survey date. Estimate 2 was made by one of the soft drink manufacturers. Of this population, males constituted 71 per cent and ac2. Data shown are for male population. counted for 68 per cent of consumption in volume. Source: Data collected from industry.

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India: The Battle of the Bottle Continues

401

CSDs were consumed more often out of home and many between meals as may be seen below:

Table 7 Pattern of CSD consumption (percentages)

Water At Home Out of Home Total With Meals Between Meals Total 92 8 100 46 54 100 Tea/Coffee 85 15 100 44 56 100 CSD 44 56 100 12 88 100

Table 8 What people drink and when

CSD Home Eating a meal at home Having a snack Watching television Relaxing Away from Home With meals With snacks Meal at school/work Fast food joints On the move Shopping At movie theatres Home or Away Working or studying Socializing At parties Celebrating special occasions Fruit Juice 9 2 11 9 19 7 10 19 23 21 11 10 12 18 22 Coffee/ Tea 23 72 46 63 24 72 52 15 36 38 12 65 54 12 19 Milk Total

4 1 6 4 37 17 29 59 22 25 76 6 14 67 55

63 25 38 23 20 4 9 7 19 16 2 19 20 3 4

100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

Source: Data obtained from industry.

The association of CSD and other beverages/drinks with activities may be seen from Table 8. The reasons cited by respondents in selecting a particular brand and type of beverage were (i) rational reasons such as being refreshed after consumption, quenching of thirst and taste, and (ii) emotion-based reasons such as image projected among friends, being popular and in thing and done thing to serve guests. It was also found that while rational reasons were cited only to the extent of about 30 to 40 per cent of respondents, this frequency did not vary much across seasons. On the other hand, emotion-based reasons were cited by about 50 to 80 per cent of respondents but varied considerably across seasons. In hot seasons, generally emotional reasons went up in frequency. It was the general opinion in the industry that soft drinks had strong associations and that purchases were heavilyinfluencedbythekindof imageeachdrinkprojected. Consistently over the world, blind tests had failed to distinguish between the actual preference of consumers of at least Coca-Cola and Pepsi; in fact in some blind tests conducted by Pepsi in 1974 (and widely publicized through Challenge Booths set up in food stores), 58 per cent of consumers were found to prefer the taste of Pepsi.6 That did not prevent them from still preferring Coke brands in real life, apparently. Hence a great deal of effort went in building images across the brands and sustaining them.

Source: Data obtained from industry.

Worldwide, Coca-Cola had built up very strong associations with the American way of life. Attempts at reorienting the image had generally proved disastrous in the past. In a well known case, in 1984, Coca-Cola announced that it would change the formula of its 99 year old brand to contain more sugar. Apparently this made it taste more like Pepsi. The product met with customer resistance with formation of consumer resistance groups. On the day of the announcement, Pepsi announced a holiday for its employees, claiming it welcomed the new Pepsi drinkers. Bottlers also added to the clamor. The noise made indicated that a substantial number of Americans regarded the traditional Coca-Cola as synonymous with motherhood and apple pie.7 Coca-Cola had to relent and reintroduce the original product as Coca-Cola Classic. Much later, in 1994, Pepsi tried repositioning its own product, canning in new blue cans. The result was equally disastrous.

entry BarrIers

The soft drink industry involved considerable economies of scale in manufacture, especially of bottle and

402

Strategic Management

can manufacture and bottling operations. The scale of economies in cans, for example, was so high that, at present levels of consumption, it was not feasible to set up can manufacturing factories that were viable. The distribution system formed another formidable entry barrier. The system needed to reach a huge number of small outlets and even in cities this was a major task. Investment in bottles as well as in other matching equipment such as chillers, vissicoolers, and ice boxes was huge. Transport vehicles were needed to transport the drinks to outlets, and these vehicles were generally owned by the bottling company and carried the logo of respective brands prominently, as did the crates and bottles themselves. Thus they could not be interchanged between different brands. The brands themselves constituted a major entry barrier. It was very expensive to launch a new brand and sustain it. However, there was scope for local brands to be developed and promoted. This was in fact done by many local brands which concentrated on particular areas. But even put together, they constituted less than 10 per cent of the market.

The advent of fruit juice based non-carbonated drinks, packed in tetrapacks, was considered an important development. Even earlier, squashes served as convenience drinks at homes, but their major problem was that they could not be carried around easily and could not be purchased on impulse. Things changed a great deal, however, when Frooti, a drink packed in handy 250 ml. pack, was introduced in 1985 by Parle and Jumpin by Godrej. These packs could be carried around, with no risks of breakage; kids found them fun, and mothers found them less troublesome. It also provided a health assurance no water of doubtful purity so that consumers very particular about water contamination (such as foreign tourists) found this product very good value for money. Frooti had been accepted for supply in trains, aircraft, and in parties as a safe, enjoyable, tasty and healthy drink. After the success of Frooti, other manufacturers had also jumped into the fray. Another new development in 1998 was fresh fruit juice, packed hygienically and with a long shelf life, named Onjus manufactured by Enkay Texofood Limited. This was promoted as a juice no different from juices extracted on the spot from fresh fruit. The promoters were optimistic about the prospects for this drink. In 1998, Onjus had become a `400 million business; with suBstItutes a competitor, Dabur with its Dabur Real, also entering, By their very nature, soft drinks were readily substitut- this market was expected to take off. Yet another development that was not to be ignored able by a variety of beverages and other soft drinks. Even though many consumers had strong preferences, the was the advent of mineral water in the Indian market. preferences were not so strong that the consumers would The pioneer of this concept in the Indian market was go out of their way to get their own brands. Consumers Parle Industries with its brand Bisleri which had almost alsoreadilyswitchedbetweendifferentflavors.Themost become a generic name. Very slow to gain acceptance at important parameter governing the eventual choice was first,mainlyinviewof itscost(about`16 for a one litre availability. If this was not ensured, all the efforts spent bottle in 1998), the market for mineral water had grown, on promotion and advertisements were of little use. This thanks to vigorous promotion and growing health conmeant that the full line of products of each manufacturer sciousness (rather, scare about possible water contaminaneeded to be stocked at retail shops that were close to- tion). It was believed that mineral water was becoming an gether. At least in this business, more was better in terms important substitute for soft drinks, especially by travelof number of retail outlets. This was expressed beauti- lers. Some people even thought that in the next few years, 8 fully by Coca-Cola in its famous line that its objective was mineral water would outsell carbonated drinks. There were a host of manufacturers of mineral wato make Coke available within an arms reach of desire in every country it was in. Competitors tried various ways ter in 1998 with two or three leading brands operating to make sure that their brands were available whenever nationally and the rest regionally. Parle Exports, with its 9 consumers felt like having a soft drink: mobile trolleys, brand Bisleri, (still controlled by Ramesh Chauhan) was employing retired personnel to intensely push their prod- the market leader with about 50 per cent market share. ucts, and so on. Railway stations were a favorite target Another major brand was Bailley, owned by Parle Agro, out of 7056 railway stations in the country, about 3000 a company controlled by Prakash Chauhan. Bailley comhad soft drink outlets. Supermarkets were another target manded a market share of about 31 per cent. Worldwide, both Coca-Cola and Pepsi owned mineral water brands, for soft drink manufacturers.

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India: The Battle of the Bottle Continues

403

Bonaqua of Coca-Cola and H20h! by Pepsi Foods. These brands, however, had not been launched in India. The market for mineral water in India as in 1998 was estimated to be around `4000 million, or, at an average price of `12 per litre, about 330 million litres. According to Mr. Ramesh Chauhan, he aimed for a consumption of 500 million litres of Bisleri by the summer of 1999.10

coMPetItIon

The two major players were Coca-Cola India and Pepsi Co. Their profiles and strengths and weaknesses are givenbelow.Twomorebrandsof anysignificancewere Campa-Cola and Sosyo.

Coca-Cola11

Coca-Cola Company was a $19 billion US company basedinAtlanta.Itsflagshipdrink,Coca-Cola,wasone of thefivebestknowntrademarksintheworld,andwas identifiedasthemostadmiredtrademarkintheworld, according to a survey conducted worldwide in 1988. Coca-Cola was developed as a formulation in 1886 by Dr. John Pemberton, a pharmacist in Atlanta. The legend goes that Dr. Pemberton, having produced the concoction in a three legged brass pot in his backyard, took it to a local chemist, Jacobs Pharmacy (of which he was part owner), and sold it through Jacob Pharmacy as a refreshing drink. The product must have been quite pleasing to the 19th century palates, for it found instant acceptance. Dr. Pembertons partner, Frank Robinson suggested the name thinking two Cs would look well in advertisementsandpennedthefamousflowingscriptwhichis also the trademark of Coca-Cola. The real development, however, took place when Asa Candler became the sole owner of Jacobs Pharmacy (at an expense of $2,300) who introduced many innovations the most important being (i)selling the concentrate to other pharmacies for a charge, (ii) heavy advertising and promotions which were ubiquitous, and (iii) the concept of bottling franchises. The famous hobble skirt bottle was designed by Root Glass Company of Terre Haute, Indiana, in 1916 and the shape was patented much later in 1997, an honor accorded to only a handful of other packages. The name Coke was also patented as a substitute for Coca-Cola. In 1919, Ernest Woodruff purchased the Coca-Cola Company from Asa Candlers heirs and in 1923 his son, Robert Woodruff, took the company to great heights. His was the motto within an arms reach of desire, making the drink available virtually everywhere, well, if not an

arms reach, certainly within the reach of a few steps. Coca-Colas association with Olympics began in 1928 in the Amsterdam Olympics, when the spectators witnessed the first lighting of the Olympic flame as well as the firstsaleof Coca-ColaatanOlympiad.TheCoca-Cola Company introduced open top coolers for store keepers in 1929 (provided at low prices by the company), the coin vending machine in 1937, and its famous lifestyle advertising emphasizing the products role in a consumers life rather than the products attributes. This varied from time to time, and the more memorable messages were: The Pause that Refreshes, The Real Thing, Things Go Better with Coke, Coke Adds Life, Have a CocaCola and a Smile, Always Coca-Cola, Coke is It and Cant Beat the Real Thing. Every Coke-person felt nostalgic about Coca-Colas decision to supply Coke, at the request of General Dwight Eisenhower during World War II, to every man in uniform for 5 cents wherever he is and whatever it costs. Coca-Cola bottling plants soon followed the American troops around the world, and even though we have no idea of how much it cost, surelythebenefitsweremanytimesover.Coca-Colabecame a dominant symbol all over the world, with a dominant market share. Even now, Coca-Cola as a brand is a leader in most of the countries, through not in India (the reader is advised not to remind Coca-Cola India executives of this!). Worldwide, Coca-Cola held almost 70 per cent of the Cola market, and in US, about 40 per cent. Pepsi Cola was the follower with about 31 per cent share in the US International sales of Coca-Cola accounted for 62 per cent of the volume in contrast to 20 per cent of Pepsis. Other worldwide brands were: Fanta, an orange flavored CSD, Sprite, a clear lime CSD, Tab, a lemon flavoredCSD,Fresca,agrapejuiceflavoredCSD,Diet Sprite, Diet Coke, Caffeine-free Coke, Cherry Coke, Diet Cherry Coke, and an orange juice NCSD, the Minute Maid. Worldwide, 37 per cent of Coca-Colas production was from independently owned bottlers; 50 per cent from plants with non-controlling interest; and 13 per cent from plants with controlling interest.

Pepsi-Cola

Pepsi-Cola was formulated in 1893 in New Bern, North Carolina, by a pharmacist, Caleb Bradham. Pepsi also expanded its network through a franchised network of bottlers. But, unlike Coca-Cola, Pepsi came to near bankruptcy a number of times. Pepsi generally competed on price. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Pepsi had sold its concentrate to bot-

404

Strategic Management

tlers at a price 20 per cent lower than Coca-Cola. The soft drink prices to the consumers were also correspondingly lower. Later in early 1950s, it increased its concentrate price to equal that of Coca-Cola and used the increased margins for advertisements and promotions. In 1933, Pepsi Cola was sold at 5 cents per bottle of 12 oz., the same price as a Coca-Cola bottle of six and half oz. In 1939, it beamed its famous radio jingle, which went on to become the second best known song in America (behind the Star Spangled Banner ): Twice as much for a nickel too, Pepsi Cola is the one for you. Unlike, the Coca-Cola Company, Pepsi, under the leadership of Donald Kendall who took over in 1963, diversifiedintoproductionof snacks(Frito-lay)andrestaurants (Pizza-hut, Taco Bell, and Kentucky Fried Chicken). As a consequence of these diversifications, Pepsi-Cola Company was renamed as PepsiCo. It was of the opinion that there were synergies possible across these businesses: chips were supposed to go well with soft drinks, and new fountain outlets could be opened in restaurants. Pepsi also had a number of powerful brands worldwide in its arsenal. It had Pepsi Free in the caffeine-free segment, Sugar Free Pepsi Free with aspartame in place of sugar, clear lemon drinks Slice and Diet Slice, Cherry Cola Slice, Cherry Pepsi, and Slice Mandarin Orange. It wasalsothefirsttointroducethethreelitreplastictakehome bottle.

coMPetItors In IndIa

India was one of the few countries in the world where Pepsi led the Coca-Cola brand in the cola segment. But since Coca-Cola also had the Parles old brands (Thums Up, Limca, etc.) in its stable, in terms of market shares of companies, Coca-Cola company held about 54 per cent share of the market as against Pepsi Co. Indias 40 per cent. Table 9 shows the market shares of the brands of the two majors.

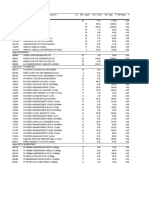

Table 9 Market shares of the soft drink brands of the majors (as on January 1998)

Coca-Cola Co. Brands Coca-Cola: 17.9% Thums Up: 17.5% Fanta: 7.9% Gold Spot: 1.0% Limca: 9.4% Citra: 0.5% Pepsi Brands Pepsi: 27.3% Mirinda: 7.9% Teem: 1.5% 7 Up: 2.5%

Brand Cola Segment (60%) Orange Clouded Lime Clear Lime

Source: Adding A Lemon, Business India, May 7, 1998; and also data obtained from the industry.

A great strength of Coca-Cola was its array of brandsfairly powerful in each segment. Pepsis noncola brands were generally weak. Pepsi had been able to build a presence in many cities. Its bastions seemed to be Mumbai, Delhi, and Ahmedabad. Coca-Cola was strong in Chennai and Kolkata; Thums Up in northern cities and in Andhra Pradesh. From the very beginning, Pepsi chose to adapt to Indian needs and preferences. It tried to associate its brand with local festivals, events, and traditions. Instead of projecting its global lineage, it used vernacular phrases, and associated with local festivals with new slogans and people. Its strategy was to introduce campaigns madeinIndiaandspecifictoIndiansettings,people,and idioms. For example, it adapted its famous US campaign line Youve Got the Right One Baby, Uh-Huh sung by Ray Charles to Yehi Hai Right Choice Baby, Aha. In Chennai, it offered a bottle of free Pepsi with idlis (a South Indian snack); in Calcutta, it linked it with local cricket tournaments; and in Delhi, with the festival of Holi. In the words of a Pepsi executive, On-the-ground activity is critical. You have to keep generating activities and increase consumption opportunities.12 Pepsi had adopted an aggressive campaign, targeted at the youth. It positioned itself as a thing for the youth. Pepsi conducted a memorable advertising campaign during the Wills World Cup in cricket in 1997, for which it bid and lost. While Coca-Cola trumpeted its drink as theofficialdrinkfortheworldcup,Pepsiconducted a campaign Nothing Official About It featuring celebritiessuchascricketerSachinTendulkarandthefilm star Akshay Kumar. The campaign, which cashed in on theanti-establishment,anti-officialaspirationsof the youth, and the campaign was considered to be highly successful, the sour grapes element not much visible. It was only much later, from mid 1997, that CocaCola also started on similar local platforms, abandoning its global ads. Till then, at least in the beginning, CocaCola campaigned their global low key and less aggressive. But in 1997, a new CEO, Mr. Donald Short took over, andlaunchedanIndia-specificcampaign,abandoningits globaltemplatesandfindingmuchwisdomintheoldadage about doing as the Romans do while in Rome. In 1998, Coca-Cola ran a series of campaigns with the theme Eat..., Sleep...., Drink only Coca-Cola, the gaps being filledatdifferenttimesbydifferenteventscurrentatthat time: such as tennis, cricket, etc. This campaign was considered to be a great success in building awareness about the Coca-Cola brands.13 According to a survey, in August 1997, only 19.4 per cent of a sample of soft drinkers

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India: The Battle of the Bottle Continues

405

population recalled seeing a Coke advertisement, while 37 per cent remembered Pepsi ads instantly. By March 1998, Coke seemed to have caught up: 32 per cent were aware of Pepsi ads and 30.4 per cent, of Coke ads.14 Pepsi continued to associate celebrities in its ad campaigns. Only in 1998 did Coca-Cola realize the need for celebrities and in September 1998, it signed up some celebrities such as cine stars Karishma Kapoor, and Amir Khan, and cricketers Srinath, Saurav Ganguly, Robin Singh, and Anil Kumble. Pepsi had in its campaigns cine star Shah Rukh Khan and cricketers Sachin Tendulkar, Ajay Jadeja, Mohammed Azharuddin, and Rahul Dravid. While Coca-Cola started sponsoring live concerts featuring Asha Bhonsle, Alisha Chinai, and Daler Mahendi, Pepsihadthrownitslotwithfilmpremieres.Andthus, the cola conflict continues, celebrity against celebrity, jingle against jingle,15 glocalization against glocalization, commented Business Today.16 Pepsi also had been agile in getting a number of events sponsored or in which it had a major presence. For example, it was expected to be associated with about 100 music related events (Coke was to be associated with about 70); with some 60 movies (Coke: 26); and 13 or so sports events (Coke: 7). Thus, Coca-Cola was seen as a me-too follower of Pepsi in India. However, lately, Coca-Cola too launched an aggressive sponsoring of events and was expected to overtake Pepsi in each event in 1999. While Pepsi positioned its cola drink clearly as the youth and fun drink, its positioning in terms of its other brands was less clear. It seemed as if most of Pepsis energies were concentrated on its cola brand. CocaColaspathwaschequered.Atfirst,afteracquiringParles brands, it tried to downplay these brands promoting its own brands. But it realized by 1997 that this was a mistake; Thums Up and Limca were too powerful indeed, and not promoting them was simply leading to their share being taken up by Pepsis brands. In 1997, CocaCola began a repositioning exercise, and began promoting all its brands vigorously. Thums Up was positioned with a macho image targeting at 20 to 29 year olds; Fanta was the fun drink for 13 to 19 year olds; and Limca was for anyone taking a breatheror, as its catch line said, take it easy. As for Coke, it was treated as a mother brand, which would build the foundation for the rest of the brands. Also, the advertising and promotion of each brand was directed to those cities and regions where it was strong. For example, Mumbai and Kolkata saw more of Thums Up, while Chandigarh saw more of Coke, while the South saw Citra more often17.

Pepsi worked with one ad agency while Coca-Cola Indiausuallyhadfourtofiveagencieswithwhomitnegotiated and got better rates. All promotions of CocaCola were national so far, while Pepsi went in for national and regional promotions. Pepsi generally chose a city or region and ran a high intensity campaign for about a month; then moved on to another city. This usually resulted to a gain in market share by about 5 to 10 percentage points in the short run and by about 3 to 5 points in the long run, in the absence of a counter campaign. Pepsi and Coca-Cola both had mechanisms for tracking their market shares. Essentially this was done through questioning the retail outlets and samples of consumers. Coca-Cola, from the beginning, invested heavily in market research and intelligence and its capabilities in this respect were believed to be much better. It could identify shifts in market shares in any market within about 37 days of the end of the period and the data were considered to be very reliable. Coca-Cola executives claimed that this enabled them to plan their campaigns andpromotionsandfinetunethem.Pepsi,beingthefirst mover, had a good network of well-trained salespersons. It was also believed that Pepsi paid the salesmen better than Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola executives believed that pay itself was not a major disadvantage, but they needed to do more and better training for their salespersons. Pepsi and Coca-Cola had built different distribution and logistic systems. Pepsi had a higher number of fountains and it had built a good number of high image clientsthankstoitsbeingthefirstmovercomparedto Coca-Cola. It operated smaller trucks which covered a shorter route while Coca-Cola had larger trucks covering longer routes. Pepsi used half depth crates (i.e., with heights covering only half the bottle) while Coca-Cola used full depth crates. The latter was believed to lead to less breakagesCoca-Colas breakage of bottles was 0.5 per cent compared to 2.5 per cent for Pepsi. From the beginning, Pepsi followed a strategy of owning and operating many bottling plants. It acquired controlling interests in numerous bottling operations guaranteeingthebottlersfinancialsupport.Thisstrategy gave control over bottling operations, but it resulted in spending a lot of managerial resources in manufacturing and labor problems. According to Business India, one of the industry managers thought that with such big investments on the ground, Pepsi may not be able to take its eye off the manufacturing ball and the moot point is whether it will be able to focus adequately on marketing at the same time, which is really the name of this game.18

406

Strategic Management

Coca-Cola, on the other hand, started with owning as little of bottling as possible. But it seems to have followed Pepsis footsteps buying up a number of bottling units. By the end of 1998, Coca-Cola owned 52 outlets across India, and was in the process of acquiring the remaining independent plants also or setting up joint ventures with majority stakes. There were 45 more independent bottlers and in 199798, Coca-Cola had signed up two joint ventures and acquired the management control of five other bottling units. Coca-Cola operated through two holding companies in IndiaHindustan Coca-Cola and Bharat Coca-Cola. They had financed four downstream joint ventures: Hindustan Coca-Cola Bottling North West (investment: `3450 million); Hindustan Coca-Cola Bottling South West (investment: `2500 million); Bharat CocaCola Bottling North East (investment: `2500 million); and Bharat Coca-Cola Bottling South West (investment: `3450 million).19 It was expected that when the franchising agreements would come up for renewal (mostly in late 1998 and early 1999), the balance units would be acquired by Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola had its plants spread out thanks to historical legacies. This made for shorter access to markets but poorer economies of scale in manufacture. On the whole, neither was believed to have a decisive advantage over other because of this factor. One and 1.5 litre bottles were emerging as important consumer preferences. These were non-returnable PET bottles, to be taken home by consumers and served within two to three days of opening the bottle. This was becomingpopularinthehousesegment.Onlyfirstquality (not recycled) PET bottles were used for this purpose. As in 1998, Pepsi had tied up for capacities for large bottles more than Coca-Cola. It was believed that fountain sales would pick up steeply inthecomingyears.Becauseof itsfirstmoveradvantage, Pepsi had been able to set up about 4000 fountains while Coca-Cola had about 1500. According to Vibha Rishi, Vice President, Marketing, Pepsi planned to add another 200,000 access points to the existing half a million, with around 50,000 new coolers in an year. Coca-Cola also had similar plans. But it was cautious over the issue of going into fountains in a big way, for it believed these had serious quality problems, especially with water. Coca-Cola was extremely sensitive to the issue of quality. Quality was a problem in this industry, for much depended on how much care the bottler took in his

operations and supplies, especially water. Any contamination found instant headlines in newspapers, and the concentrate manufacturers believed that it hurt them almost entirely, not the bottlers (many in the public did not even know the difference between bottlers and concentrate manufacturers). Coca-Cola believed that its quality checks were very stringent and of world class, and far superior to Pepsis. It thought that, unless the quality issues were sorted out, it would not be a good idea to get into fountains in a big way. ItwasbelievedthatPepsihadaverythinheadoffice. Much of the initiatives were left to the people at the regional levels, and they could launch campaigns without reference to even the Indian head office. Thus, it was speculated that the Chennai idli campaign was done at the initiative of the Chennai people alone.20 The New York office also left the Indian executives to plan and execute work in their own way. On the other hand, CocaCola had a fairly large head office in Delhi, with most of the decisions on campaigns, promotions, and pricing takenattheheadofficelevel.InturnitsAtlantaoffice also held the Indian company on a tight leash. Recently, however, Coca-Cola also seemed to have changed its approach,andhadstartedgivingmorefreedomtothefield personnel. Coca-Cola executives were of the opinion that over time, as in other countries in the world, their brands would dominate, with suitable and adequate promotion and advertising support. They also believed that the market would continue to grow at the rate of at least 12 to 15 per cent a year, perhaps as much as 30 per cent a year and their market share (of Coca-Cola brands, not Parle brands) would steadily inch up.

assIgnMent QuestIons

1. ConductanindustryanalysisusingPortersfiveforces model and identify action implications in each for Coca-Cola India. 2. Identify strategic questions facing Coca-Cola India (fiveatthemost). 3. Fromtheprofilesof Coca-ColaandPepsigivenin the case, assess the relative strengths and weaknesses of each. It may be useful to do this under different scenarios. 4. Develop a set of recommendations for Coca-Cola India (remember to take into account Pepsis likely offensive and defensive/retaliatory moves).

Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi in India: The Battle of the Bottle Continues

407

Notes

1. Leading the Way, Business India, January 1528, 1996, p.59. 2. Donald short, Ceo, Coca-Cola India, quoted by Business India in turning on the Heat, June 29July 12, 1998. 3. One unit case was defined as 24 bottles of 250 ml. each; recently since most of the bottles are sold with 300 ml. capacity, one unit case is referred to as 24 bottles of 300 ml. each. 4. Leading the Way, Business India, January 1528, 1996, p.59. 5. events were a recent development in India, and referred to particular shows (such as fashion shows) organized to promote a particular brand. These were quite big affairs, with celebrities gracing the occasion, of course for a suitable fee. 6. Rebecca Wayland, Coca-Cola versus Pepsi-Cola in the Soft Drink Industry, case material of Harvard Business school, 1991. Case # 9-391-179 (case prepared under the supervision of Prof. Michael E. Porter). 7. ibid. 8. Ramesh Chauhan, for example, is reported to have shared this view. Can Coca-Cola Bottle Up the Chauhans?, Business Today, August 22, 1998. 9. the brand was owned by Acqua Mineral, a wholly owned subsidiary of Parle exports. 10. Bottling Up Strategies for the War of the Waters, Business Today, september 721, 1998. 11. Material in this section and the next on Pepsi are based on documents given by Coca-Cola India and the Harvard Case, Coca-Cola versus Pepsi-Cola and the Soft Drink Industry. 12. Why Coke should Be more Like Pepsi, Business Today, August 721, 1997. 13. turning on the Heat, Business India, June 29July 12, 1998. 14. ibid. 15. Coca-Cola, for instance, coined its jingle Ala-Re-Aya which was preempting Pepsis Sachin Aya Re jingle. Both were based on the same film song, and Coca-Cola was involved in some controversy over its jingle. 16. The Cola Warriors Indian Summer, Business Today, september 7, 1998. 17. turning on the Heat, Business India, June 29July 12, 1998. 18. that Passion to Win, Business India, January 1528, 1996, pp.65. 19. Can Coca-Cola Bottle Up the Chauhans?, Business Today, August 22, 1998. 20. Why Coke Should Be More Like Pepsi, Business Today, August 721, 1997.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- BS en 00631-1-1993 (1999)Document12 paginiBS en 00631-1-1993 (1999)vewigop197Încă nu există evaluări

- OG Covid Recipes: Updated Automatically Every 5 MinutesDocument98 paginiOG Covid Recipes: Updated Automatically Every 5 MinutesMyassar AlostaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DKBMDocument66 paginiDKBMArif sprÎncă nu există evaluări

- Osteria Mozza Sample Dinner Menu - 15dec FINAL UaDocument1 paginăOsteria Mozza Sample Dinner Menu - 15dec FINAL UaJ FÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 31 Digital Issue (18 Aug) of Travel Weekly MagazineDocument45 paginiThe 31 Digital Issue (18 Aug) of Travel Weekly MagazineVietnam TravelweeklyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection of Regional Culture and Image in The Form of Culinary Tourism RajasthanDocument8 paginiReflection of Regional Culture and Image in The Form of Culinary Tourism RajasthanEditor IJTSRDÎncă nu există evaluări

- 40 Contoh Soal Tensen Pilihan GandaDocument8 pagini40 Contoh Soal Tensen Pilihan GandaAnggita SabilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Butter Chicken - Cafe DelitesDocument2 paginiButter Chicken - Cafe DelitesoeikeebaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Company ListDocument756 paginiCompany ListUpender Bhati0% (1)

- Important Days PDF Related To Agriculture and Rural Development For Nabard Grade ADocument6 paginiImportant Days PDF Related To Agriculture and Rural Development For Nabard Grade ADibyashree BishwabandyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Recipes Rice DumplingsDocument7 paginiRecipes Rice DumplingsLowÎncă nu există evaluări

- India's PopulationDocument36 paginiIndia's PopulationsachinvrushaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course 6 - American Think 2nd EdtDocument26 paginiCourse 6 - American Think 2nd EdtAdrian GalanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Data Base StockDocument75 paginiData Base StockSefhiantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- English With Gopal Verma: PrepositionDocument4 paginiEnglish With Gopal Verma: PrepositionHarish Yadav100% (1)

- Crown Perth Restaurants 88 Noodle Bar Main MenuDocument1 paginăCrown Perth Restaurants 88 Noodle Bar Main MenuBenoit NouguierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Industry Validation Quality Assurance ManagerDocument8 paginiIndustry Validation Quality Assurance ManagerNikhil ChaudharyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chap14 VietnamDocument3 paginiChap14 VietnamVincent Kyle BernabeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Additional ShellsDocument124 paginiAdditional ShellsVishnu PrasannaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Franchisee Price List: Siomai KingDocument2 paginiFranchisee Price List: Siomai KingMIGNONETTE ERIM DULAYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mumbai Company DataDocument8 paginiMumbai Company DataS4HolidaysÎncă nu există evaluări

- San Juan Con IvaDocument34 paginiSan Juan Con IvaLa 60 MarketingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bordeaux Wine Information Bordeaux Is Probably The Most Well-KnowDocument25 paginiBordeaux Wine Information Bordeaux Is Probably The Most Well-KnowOwm Close CorporationÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 4 IHRM CIA 1Document19 paginiGroup 4 IHRM CIA 1VAIBHAV JAIN 1923671Încă nu există evaluări

- Lecciones 6-10 Principiantes A1Document10 paginiLecciones 6-10 Principiantes A1Yhyleer Yhourdy Principe JaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Food Fest MainDocument8 paginiInternational Food Fest MainMarufa BegumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism Management Final AssignmentDocument7 paginiFaculty of Hospitality and Tourism Management Final AssignmentManisha RegmiÎncă nu există evaluări

- All Linear Equation Questions From CAT Previous PapersDocument26 paginiAll Linear Equation Questions From CAT Previous PapersSima DuttaÎncă nu există evaluări

- RCMAR Retreat 2021 Agenda DetailsDocument2 paginiRCMAR Retreat 2021 Agenda DetailsDinesh MendheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Y5 HL Summer Block 4 Converting Units 2020Document8 paginiY5 HL Summer Block 4 Converting Units 2020طائر مهاجرÎncă nu există evaluări