Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cases

Încărcat de

Lacerna KojDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cases

Încărcat de

Lacerna KojDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

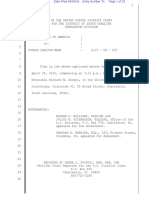

THIRD DIVISION

[G.R. No. 155555. August 16, 2005]

ISABEL P. PORTUGAL and JOSE DOUGLAS PORTUGAL JR., petitioners, vs. LEONILA PORTUGAL-BELTRAN, respondent.

DECISION

CARPIO MORALES, J.:

Petitioners Isabel P. Portugal and her son, Jose Douglas Portugal Jr., assail the September 24, 2002[1] Decision of the Court of Appeals affirming that of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Caloocan City, Branch 124[2] which dismissed, after trial, their complaint for annulment of title for failure to state a cause of action and lack of jurisdiction.

From the records of the case are gathered the following material allegations claims of the parties which they sought to prove by testimonial and documentary evidence during the trial of the case:

On November 25, 1942, Jose Q. Portugal (Portugal) married Paz Lazo.[3]

On May 22, 1948, Portugal married petitioner Isabel de la Puerta.[4]

On September 13, 1949, petitioner Isabel gave birth to a boy whom she named Jose Douglas Portugal Jr., her herein co-petitioner.[5]

On April 11, 1950, Paz gave birth to a girl, Aleli,[6] later baptized as Leonila Perpetua Aleli Portugal, herein respondent.[7]

On May 16, 1968, Portugal and his four (4) siblings executed a Deed of ExtraJudicial Partition and Waiver of Rights[8] over the estate of their father, Mariano Portugal, who died intestate on November 2, 1964.[9] In the deed, Portugals siblings waived their rights, interests, and participation over a 155 sq. m. parcel of land located in Caloocan in his favor.[10]

On January 2, 1970, the Registry of Deeds for Caloocan City issued Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT) No. 34292 covering the Caloocan parcel of land in the name of Jose Q. Portugal, married to Paz C. Lazo.[11]

On February 18, 1984, Paz died.

On April 21, 1985, Portugal died intestate.

On February 15, 1988, respondent executed an Affidavit of Adjudication by Sole Heir of Estate of Deceased Person[12] adjudicating to herself the Caloocan parcel of land. TCT No. 34292/T-172[13] in Portugals name was subsequently cancelled and in its stead TCT No. 159813[14] was issued by the Registry of Deeds for Caloocan City on March 9, 1988 in the name of respondent, Leonila Portugal-Beltran, married to Merardo M. Beltran, Jr.

Later getting wind of the death in 1985 of Portugal and still later of the 1988 transfer by respondent of the title to the Caloocan property in her name, petitioners filed before the RTC of Caloocan City on July 23, 1996 a complaint[15] against respondent for annulment of the Affidavit of Adjudication executed by her and the transfer certificate of title issued in her name.

In their complaint, petitioners alleged that respondent is not related whatsoever to the deceased Portugal, hence, not entitled to inherit the Caloocan parcel of land and that she perjured herself when she made false representations in her Affidavit of Adjudication.

Petitioners accordingly prayed that respondents Affidavit of Adjudication and the TCT in her name be declared void and that the Registry of Deeds for Caloocan be ordered to cancel the TCT in respondents name and to issue in its stead a new one in their (petitioners) name, and that actual, moral and exemplary damages and attorneys fees and litigation expenses be awarded to them.

Following respondents filing of her answer, the trial court issued a Pre-Trial Order chronicling, among other things, the issues as follows:

a. Which of the two (2) marriages contracted by the deceased Jose Q. Portugal Sr., is valid?

b. Which of the plaintiff . . . Jose Portugal Jr. and defendant Leonila P. Beltran is the legal heir of the deceased Jose Q. Portugal Sr.?

c. Whether or not TCT No. 159813 was issued in due course and can still be contested by plaintiffs.

d. Whether or not plaintiffs are entitled to their claims under the complaint.[16] (Underscoring supplied)

After trial, the trial court, by Decision of January 18, 2001,[17] after giving an account of the testimonies of the parties and their witnesses and of their documentary evidence, without resolving the issues defined during pre-trial, dismissed the case for lack of cause of action on the ground that petitioners status and right as putative heirs had not been established before a probate (sic) court, and lack of jurisdiction over the case, citing Heirs of Guido and Isabel Yaptinchay v. Del Rosario.[18]

In relying on Heirs of Guido and Isabel Yaptinchay, the trial court held:

The Heirs of Yaptinchay case arose from facts not dissimilar to the case at

bar.

xxx

In the instant case, plaintiffs presented a Marriage Contract, a Certificate of Live Birth, pictures (sic) and testimonial evidence to establish their right as heirs of the decedent. Thus, the preliminary act of having a status and right to the estate of the decedent, was sought to be determined herein. However, the establishment of a status, a right, or a particular fact is remedied through a special proceeding (Sec. 3(c), Rule 1, 1997 Rules of Court), not an ordinary civil action whereby a party sues another for the enforcement or protection of a right, or the protection or redress of a wrong (ibid, a). The operative term in the former is to establish, while in the latter, it is to enforce, a right. Their status and right as putative heirs of the decedent not having been established, as yet, the Complaint failed to state a cause of action.

The court, not being a probate (sic) court, is without jurisdiction to rule on plaintiffs cause to establish their status and right herein. Plaintiffs do not have the personality to sue (Secs. 1 and 2, Rule 3, in relation to Secs. 1 and 2, Rule 2, supra).[19] (Italics in the original; emphasis and underscoring supplied).

Petitioners thereupon appealed to the Court of Appeals, questioning the trial courts ratio decedendi in dismissing the case as diametrically opposed to this Courts following ruling in Cario v. Cario,[20] viz:

Under Article 40 of the Family Code, the absolute nullity of a previous marriage may be invoked for purposes of remarriage on the basis solely of a final judgment declaring such previous marriage void. Meaning, where the absolute nullity of a previous marriage is sought to be invoked for purposes of contracting a second marriage, the sole basis acceptable in law, for said projected marriage to be free from legal infirmity, is a final judgment declaring the previous void. (Domingo v. Court of Appeals, 226 SCRA 572, 579 [1993]) However, for purposes other than remarriage, no judicial action is necessary to declare a marriage an absolute nullity. For other purposes, such as but not limited to the determination of heirship, legitimacy or illegitimacy of a child, settlement of estate, dissolution of property regime, or

a criminal case for that matter, the court may pass upon the validity of marriage even after the death of the parties thereto, and even in a suit not directly instituted to question the validity of said marriage, so long as it is essential to the determination of the case. (Nial, et al. v. Bayadog, GR No. 13378, March 14, 2000). In such cases, evidence must be adduced, testimonial or documentary, to prove the existence of grounds rendering such a previous marriage an absolute nullity. These need not be limited solely to an earlier final judgment of a court declaring such previous marriage void. (Domingo v. Court of Appeals, supra) (Emphasis and underscoring supplied).

Conceding that the ruling in Cario was promulgated (in 2001) subsequent to that of Heirs of Guido and Isabel Yaptinchay (in 1999), the appellate court found Cario to be inapplicable, however, to the case in this wise:

To be borne in mind is the fact that the main issue in the Cario case was the validity of the two marriages contracted by the deceased SPO4 Santiago Cario, whose death benefits was the bone of contention between the two women both named Susan (viz., Susan Nicdao Cario and Susan Yee Cario) both of whom he married. It is not disputed in said case that SPO4 S. Cario contracted two marriages with said two women during his lifetime, and the only question was: which of these two marriages was validly celebrated? The award of the death benefits of the deceased Cario was thus, merely an incident to the question of which of the two marriages was valid. Upon the other hand, the case at bench is of a different milieu. The main issue here is the annulment of title to property. The only undisputed fact in this case is that the deceased Jose Portugal, during his lifetime, owned a parcel of land covered by Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT) No. T-34292. However, here come two contending parties, herein plaintiffs-appellants and defendantappellee, both now insisting to be the legal heir(s) of the decedent. x x x. The status and rights of the parties herein have not, therefore, been definitively established, as yet. x x x. Necessarily and naturally, such questions as to such status or right must be properly ventilated in an appropriate special proceeding, not in an ordinary civil action, whereunder a party sues another for the enforcement or protection of a right, or the protection or redress of a wrong. The institution of an ordinary civil suit for that purpose in the present case is thus impermissible. For it is axiomatic that what the law prohibits or forbids directly, it cannot permit or allow indirectly. To permit, or allow, a declaration of heirship, or the establishment of the legitimacy or illegitimacy of a child to be determined in an ordinary civil action, not in an appropriate special proceeding brought for that

purpose, is thus to impinge upon this axiom. x x x[21] (Emphasis in the original, underscoring supplied).

The appellate court, by Decision of September 24, 2002,[22] thus affirmed the trial courts dismissal of the case.

Hence, the present Petition for Review on Certiorari,[23] faulting the appellate court to have erred when

I.

. . . it affirmed the RTC decision dismissing the initiatory complaint as it failed to state a cause of action.

II.

. . . (i) it applied the ruling in Heirs of Guido [and Isabel] Yaptingchay despite the existence of a later and contrary ruling in Cario, and (ii) when the Honorable CA and the lower court failed to render judgment based on the evidence presented relative to the issues raised during pre-trial, . . .[24] (Emphasis and underscoring supplied).

Petitioners thus prayed as follows:

WHEREFORE, it is respectfully prayed of this Honorable Supreme Court that the questioned CA decision be reversed, and a new one entered in accordance with the prayers set forth in the instant complaint based on the above disquisition and evidence adduced by petitioners in the court a quo.

IN THE ALTERNATIVE, should the Honorable Supreme Court find that the pronouncements in Cario apply, a decision be entered remanding to the

court a quo the determination of the issues of which of the two marriages is valid, and the determination of heirship and legitimacy of Jose Jr. and Leonila preparatory to the determination of the annulment of title issued in the name of Leonila.

Other relief and remedy just and equitable in the premises are likewise prayed for.[25] (Underscoring supplied).

Petitioners, in the main, argue that the appellate court misapplied Heirs of Guido and Isabel Yaptinchay and in effect encouraged multiplicity of suits which is discouraged by this Court as a reading of Cario shows; that Cario allows courts to pass on the determination of heirship and the legitimacy or illegitimacy of a child so long as it is necessary to the determination of the case; and that contrary to the appellate courts ruling, they had established their status as compulsory heirs.

In the main, the issue in the present petition is whether petitioners have to institute a special proceeding to determine their status as heirs before they can pursue the case for annulment of respondents Affidavit of Adjudication and of the TCT issued in her name.

In the above-cited case of Heirs of Guido and Isabel Yaptinchay,[26] the therein petitioners executed on March 17, 1994 an extrajudicial settlement of the estate of the deceased Guido and Isabel Yaptinchay, owners-claimants of the two lots mentioned therein. They later discovered on August 26, 1994 that a portion, if not all, of the two lots had been titled in the name of the therein respondent Golden Bay Realty and Development Corporation which in turn sold portions thereof to the therein individual respondents. The therein petitioners Heirs thus filed a complaint for annulment of titles. The therein respondents moved to dismiss the case for failure of the therein petitioners to, inter alia, state a cause of action and prove their status as heirs. The trial court granted the motion to dismiss in this wise:

But the plaintiffs who claimed to be the legal heirs of the said Guido and Isabel Yaptinchay have not shown any proof or even a semblance of it except the allegations that they are the legal heirs of the aforementioned Yaptinchaysthat they have been declared the legal heirs of the deceased

couple. Now, the determination of who are the legal heirs of the deceased couple must be made in the proper special proceedings in court, and not in an ordinary suit for reconveyance of property. This must take precedence over the action for reconveyance . . .[27] (Italics in the original; underscoring supplied).

On petition for certiorari by the Heirs, this Court, albeit holding that the petition was an improper recourse, found that the trial court did not commit grave abuse of discretion in dismissing the case. Citing Litam et al. v. Rivera[28] and Solivio v. Court of Appeals,[29] this Court held that the declaration of heirship can be made only in a special proceeding inasmuch as the petitioners here are seeking the establishment of a status or right.

In the above-cited case of Litam,[30] Gregorio Dy Tam instituted a special proceeding for issuance of letters of administration before the then Court of First Instance (CFI) of Rizal, alleging in his petition that he is the son of Rafael Litam who died in Manila on January 10, 1951 and is survived by him and his therein named seven (7) siblings who are children of the decedent by his marriage to Sia Khin celebrated in China in 1911; that the decedent contracted in 1922 in the Philippines another marriage with Marcosa Rivera; and that the decedent left neither a will nor debt. Dy Tam thus prayed for the issuance of letters of administration to Marcosa Rivera, the surviving spouse of the decedent. The CFI granted the petition and issued letters of administration to, on Marcosas request, her nephew Arminio Rivera.

While the special proceeding was pending, Dy Tam and his purported siblings filed a civil case before the same court, against the estate of Rafael Litam administrator Arminio Rivera and Remedios R. Espiritu, duly appointed guardian of Marcosa. In their complaint, Dy Tam and his purported siblings substantially reproduced the allegations made in his petition in the special proceeding, with the addition of a list of properties allegedly acquired during the marriage of the decedent and Marcosa.

Finding the issue raised in the civil case to be identical to some unresolved incidents in the special proceeding, both were jointly heard by the trial court, following which it rendered a decision in the civil case dismissing it, declaring, inter alia, that the plaintiffs Dy Tam et al. are not the children of the decedent whose only surviving heir is Marcosa.

On appeal to this Court by Dy Tam et al., one of the two issues raised for determination was whether they are the legitimate children of Rafael Litam.

This Court, holding that the issue hinged on whether Rafael Litam and Sia Khin were married in 1911, and whether Rafael Litam is the father of appellants Dy Tam et al., found substantially correct the trial courts findings of fact and its conclusion that, among other things, the birth certificates of Dy Tam et al. do not establish the identity of the deceased Rafael Litam and the persons named therein as father [and] it does not appear in the said certificates of birth that Rafael Litam had in any manner intervened in the preparation and filing thereof; and that [t]he other documentary evidence presented by [them] [is] entirely immaterial and highly insufficient to prove the alleged marriage between the deceased Rafael Litam and Sia Khin and [their] alleged status . . . as children of said decedent.

This Court went on to opine in Litam, however, that the lower court should not have declared, in the decision appealed from, that Marcosa is the only heir of the decedent, for such declaration is improper in the [civil case], it being within the exclusive competence of the court in [the] [s]pecial [p]roceeding.

In Solivio,[31] also cited in Heirs of Guido and Isabel Yaptinchay, there was a special proceeding for the settlement of the estate of the deceased, who was a soltero, filed before the RTC of Iloilo. In the special proceeding, Branch 23 of said court declared as sole heir Celedonia Solivio, the decedents maternal aunt-half sister of his mother. Concordia Javellana-Villanueva, the decedents paternal aunt-sister of his father, moved to reconsider the courts order declaring Celedonia Solivio as sole heir of the decedent, she claiming that she too was an heir. The court denied the motion on the ground of tardiness. Instead of appealing the denial of her motion, Concordia filed a civil case against Celedonia before the same RTC, for partition, recovery of possession, ownership and damages. The civil case was raffled to Branch 26 of the RTC, which rendered judgment in favor of Concordia. On appeal by Celedonia, the appellate court affirmed the said judgment.

On petition for review filed before this Court by Celedonia who posed, among

other issues, whether Branch 26 of the RTC of Iloilo had jurisdiction to entertain [the civil action] for partition and recovery of Concordia Villanuevas share of the estate of [the deceased] while the [estate] proceedings . . . were still pending . . . in Branch 23 of the same court, this Court held that [i]n the interest of orderly procedure and to avoid confusing and conflicting dispositions of a decedents estate, a court should not interfere with [estate] proceedings pending in a co-equal court, citing Guilas v. CFI Judge of Pampanga.[32]

This Court, however, in Solivio, upon [c]onsidering that the estate proceedings are still pending, but nonetheless [therein private respondentConcordia Villanueva] had lost her right to have herself declared as co-heir in said proceedings, opted to proceed to discuss the merits of her claim in the interest of justice, and declared her an heir of the decedent.

In Guilas[33] cited in Solivio, a project of partition between an adopted daughter, the therein petitioner Juanita Lopez Guilas (Juanita), and her adoptive father was approved in the proceedings for the settlement of the testate estate of the decedent-adoptive mother, following which the probate court directed that the records of the case be archived.

Juanita subsequently filed a civil action against her adoptive father to annul the project of partition on the ground of lesion, preterition and fraud, and prayed that her adoptive father immediately deliver to her the two lots allocated to her in the project of partition. She subsequently filed a motion in the testate estate proceedings for her adoptive father to deliver to her, among other things, the same two lots allotted to her.

After conducting pre-trial in the civil case, the trial court, noting the parties agreement to suspend action or resolution on Juanitas motion in the testate estate proceedings for the delivery to her of the two lots alloted to her until after her complaint in the civil case had been decided, set said case for trial.

Juanita later filed in the civil case a motion to set aside the order setting it for trial on the ground that in the amended complaint she, in the meantime, filed, she acknowledged the partial legality and validity of the project of partition insofar as she was allotted the two lots, the delivery of which she

was seeking. She thus posited in her motion to set aside the April 27, 1966 order setting the civil case for hearing that there was no longer a prejudicial question to her motion in the testate estate proceedings for the delivery to her of the actual possession of the two lots. The trial court, by order of April 27, 1966, denied the motion.

Juanita thereupon assailed the April 27, 1966 order before this Court.

The probate courts approval of the project of partition and directive that the records of the case be sent to the archives notwithstanding, this Court held that the testate estate proceedings had not been legally terminated as Juanitas share under the project of partition had not been delivered to her. Explained this Court:

As long as the order of the distribution of the estate has not been complied with, the probate proceedings cannot be deemed closed and terminated (Siguiong vs. Tecson, supra.); because a judicial partition is not final and conclusive and does not prevent the heir from bringing an action to obtain his share, provided the prescriptive period therefor has not elapse (Mari vs. Bonilla, 83 Phil., 137). The better practice, however, for the heir who has not received his share, is to demand his share through a proper motion in the same probate or administration proceedings, or for re-opening of the probate or administrative proceedings if it had already been closed, and not through an independent action, which would be tried by another court or Judge which may thus reverse a decision or order of the probate o[r] intestate court already final and executed and re-shuffle properties long ago distributed and disposed of (Ramos vs. Ortuzar, 89 Phil. 730, 741-742; Timbol vs. Cano, supra,; Jingco vs. Daluz, L-5107, April 24, 1953, 92 Phil. 1082; Roman Catholic vs. Agustines, L-14710, March 29, 1960, 107 Phil., 455, 460-461).[34] (Emphasis and underscoring supplied).

This Court thus set aside the assailed April 27, 1966 order of the trial court setting the civil case for hearing, but allowed the civil case to continue because it involves no longer the two lots adjudicated to Juanita.

The common doctrine in Litam, Solivio and Guilas in which the adverse parties are putative heirs to the estate of a decedent or parties to the special

proceedings for its settlement is that if the special proceedings are pending, or if there are no special proceedings filed but there is, under the circumstances of the case, a need to file one, then the determination of, among other issues, heirship should be raised and settled in said special proceedings. Where special proceedings had been instituted but had been finally closed and terminated, however, or if a putative heir has lost the right to have himself declared in the special proceedings as co-heir and he can no longer ask for its re-opening, then an ordinary civil action can be filed for his declaration as heir in order to bring about the annulment of the partition or distribution or adjudication of a property or properties belonging to the estate of the deceased.

In the case at bar, respondent, believing rightly or wrongly that she was the sole heir to Portugals estate, executed on February 15, 1988[35] the questioned Affidavit of Adjudication under the second sentence of Rule 74, Section 1 of the Revised Rules of Court.[36] Said rule is an exception to the general rule that when a person dies leaving a property, it should be judicially administered and the competent court should appoint a qualified administrator, in the order established in Sec. 6, Rule 78 in case the deceased left no will, or in case he did, he failed to name an executor therein. [37]

Petitioners claim, however, to be the exclusive heirs of Portugal. A probate or intestate court, no doubt, has jurisdiction to declare who are the heirs of a deceased.

It appearing, however, that in the present case the only property of the intestate estate of Portugal is the Caloocan parcel of land,[38] to still subject it, under the circumstances of the case, to a special proceeding which could be long, hence, not expeditious, just to establish the status of petitioners as heirs is not only impractical; it is burdensome to the estate with the costs and expenses of an administration proceeding. And it is superfluous in light of the fact that the parties to the civil case subject of the present case, could and had already in fact presented evidence before the trial court which assumed jurisdiction over the case upon the issues it defined during pre-trial.

In fine, under the circumstances of the present case, there being no compelling reason to still subject Portugals estate to administration

proceedings since a determination of petitioners status as heirs could be achieved in the civil case filed by petitioners,[39] the trial court should proceed to evaluate the evidence presented by the parties during the trial and render a decision thereon upon the issues it defined during pre-trial, which bear repeating, to wit:

1. Which of the two (2) marriages contracted by the deceased Jose Q. Portugal, is valid;

2. Which of the plaintiff, Jose Portugal Jr. and defendant Leonila P. Beltran is the legal heir of the deceased Jose Q. Portugal (Sr.);

3. Whether or not TCT No. 159813 was issued in due course and can still be contested by plaintiffs;

4. Whether or not plaintiffs are entitled to their claim under the complaint. [40]

WHEREFORE, the petition is hereby GRANTED. The assailed September 24, 2002 Decision of the Court of Appeals is hereby SET ASIDE.

Let the records of the case be REMANDED to the trial court, Branch 124 of the Regional Trial Court of Caloocan City, for it to evaluate the evidence presented by the parties and render a decision on the above-enumerated issues defined during the pre-trial.

No costs.

SO ORDERED.

Panganiban, (Chairman), Sandoval-Gutierrez, Corona, and Garcia, JJ., concur.

[1] Rollo at 49-56.

[2] Records at 212-230.

[3] Exh. 3, Folder of Exhibits.

[4] Exh. A, Folder of Exhibits.

[5] Exh. B, Folder of Exhibits.

[6] Exh. 4, Folder of Exhibits.

[7] Exh. 5, Folder of Exhibits.

[8] Exh. G, Folder of Exhibits.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Exh. C, Folder of Exhibits.

[12] Exh. E, Folder of Exhibits.

[13] Exh. C, Folder of Exhibits

[14] Exh. D, Folder of Exhibits.

[15] Records at 1-5.

[16] Id. at 78-80.

[17] Id. at 212-230.

[18] 304 SCRA 18 (1999).

[19] Records at 228-230.

[20] 351 SCRA 127 (2001).

[21] CA Decision, Rollo at 49, 52-54.

[22] Id. at 49-56.

[23] Id. at 3-46.

[24] Id. at 14.

[25] Id. at 43-44.

[26] Supra, note 18.

[27] Id. at 22.

[28] 100 Phil. 364 (1956).

[29] 182 SCRA 119 (1990).

[30] Supra, note 28.

[31] Supra, note 29.

[32] 43 SCRA 111 (1972).

[33] Ibid.

[34] Guilas v. Judge of the Court of First Instance of Pampanga, supra at 117 (1972).

[35] Exh. E, Folder of Exhibits.

[36] SEC. 1 Extrajudicial settlement by agreement between heirs. If the decedent left no will and no debts and the heirs are all of age, or the minors are represented by their judicial or legal representatives duly authorized for the purpose, the parties may, without securing letters of administration, divide the estate among themselves as they see fit by means of a public instrument filed in the office of the register of deeds, and should they disagree, they may do so in an ordinary action of partition. If there is only one heir, he may adjudicate to himself the entire estate by means of an affidavit filed in the office of the register of deeds. The parties to an extrajudicial settlement, whether by public instrument or by stipulation in a pending action for partition, or the sole heir who adjudicates the entire estate

to himself by means of an affidavit shall file, simultaneously with and as a condition precedent to the filing of the public instrument, or stipulation in the action for partition, or of the affidavit in the office of the register of deeds, a bond with the said register of deeds, in an amount equivalent to the value of the personal property involved as certified to under oath by the parties concerned and conditioned upon the payment of any just claim that may be filed under section 4 of this rule. It shall be presumed that the decedent left no debts if no creditor files a petition for letters of administration within two (2) years after the death of the decedent.

The fact of the extrajudicial settlement or administration shall be published in a newspaper of general circulation in the manner provided in the next succeeding section; but no extrajudicial settlement shall be binding upon any person who has not participated therein or had no notice thereof. (Underscoring supplied).

[37] Herrera, Remedial Law III-A, p. 31 (2005), citing Utulo v. Leona Pasion Vda. de Garcia, 66 Phil. 302 (1938).

[38] Vide Affidavit of Adjudication by Sole Heir of Estate of [Portugal], supra, note 12.

[39] Vide Pereira v. Court of Appeals, 174 SCRA 154 (1989); Intestate Estate of Mercado v. Magtibay, 96 Phil. 383 (1955).

[40] Supra, note 16. ============================================== ============================== THIRD DIVISION

[G.R. No. 168799, June 27, 2008]

EUHILDA C. TABUADA, PETITIONER, VS. HON. J. CEDRICK O. RUIZ, AS

PRESIDING JUDGE OF THE REGIONAL TRIAL COURT, BRANCH 39, ILOILOCITY ERLINDA CALALIMAN-LEDESMA AND YOLANDA CALALIMAN- TAGRIZA, RESPONDENT.

DECISION

NACHURA, J.:

In this petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, petitioner assails the March 2, 2005 Order[1] of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Iloilo City, Branch 39 in Special Proceedings (Sp. Proc.) No. 5198 and the May 20, 2005 Resolution[2] of the trial court denying the motion for the reconsideration of the challenged order.

The very simple issue raised for our resolution in this case surfaced when the parties in Sp. Proc. No. 5198 (the proceedings for the settlement of the intestate estate of the late Jose and Paciencia Calaliman) manifested to the RTC their desire to amicably settle the case. In light of the said manifestation, the trial court issued the following Order[3] on December 6, 2004:

In view of the strong manifestation of the parties herein and their respective counsel that they will be able to raise (sic) an amicable settlement, finally, on or before 25 December 2004, the Court will no longer be setting the pending incidents for hearing as the parties and their counsel have assured this Court that they are going to submit a "Motion for Judgment Based On An Amicable Settlement" on or before 25 December 2004.

Atty. Honorato Sayno Jr., Atty. Gregorio Rubias and Atty. Raul Retiro are notified in open court.

Serve a copy of this Order to Atty. Rean Sy.

SO ORDERED.[4]

The RTC, however, on March 2, 2005, invoking Section 3,[5] Rule 17, of the Rules of Court, terminated the proceedings on account of the parties' failure to submit the amicable settlement and to comply with the afore-quoted December 6, 2004 Order. The trial court, in the challenged order of even date, likewise denied all the motions filed by the parties.[6]

Petitioner, the administratrix of the estate, and private respondents separately moved for the reconsideration of the March 2, 2005 Order arguing, among others, that the termination of the case was premature, there being yet no payment of the debts and distribution of the estate, and that they had already prepared all the necessary papers for the amicable settlement.[7] Despite the said pleas for reconsideration, the trial court remained firm in its position to terminate the proceedings; hence, in the assailed May 20, 2005 Resolution,[8] it affirmed its earlier order. Dissatisfied, petitioner scuttles to this Court via Rule 45.[9]

The petition is granted.

While a compromise agreement or an amicable settlement is very strongly encouraged, the failure to consummate one does not warrant any procedural sanction, much less provide an authority for the court to jettison the case. [10] Sp. Proc. No. 5198 should not have been terminated or dismissed by the trial court on account of the mere failure of the parties to submit the promised amicable settlement and/or the Motion for Judgment Based On An Amicable Settlement. Given the non-contentious nature of special proceedings [11] (which do not depend on the will of an actor, but on a state or condition of things or persons not entirely within the control of the parties interested), its dismissal should be ordered only in the extreme case where the termination of the proceeding is the sole remedy consistent with equity and justice, but not as a penalty for neglect of the parties therein.[12]

The third clause of Section 3, Rule 17, which authorizes the motu propio dismissal of a case if the plaintiff fails to comply with the rules or any order of the court, [13] cannot even be used to justify the convenient, though erroneous, termination of the proceedings herein. An examination of the December 6, 2004 Order[14] readily reveals that the trial court neither required the submission of the amicable settlement or the aforesaid Motion

for Judgment, nor warned the parties that should they fail to submit the compromise within the given period, their case would be dismissed.[15] Hence, it cannot be categorized as an order requiring compliance to the extent that its defiance becomes an affront to the court and the rules. And even if it were worded in coercive language, the parties cannot be forced to comply, for, as aforesaid, they are only strongly encouraged, but are not obligated, to consummate a compromise. An order requiring submission of an amicable settlement does not find support in our jurisprudence and is premised on an erroneous interpretation and application of the law and rules.

Lastly, the Court notes that inconsiderate dismissals neither constitute a panacea nor a solution to the congestion of court dockets. While they lend a deceptive aura of efficiency to records of individual judges, they merely postpone the ultimate reckoning between the parties. In the absence of clear lack of merit or intention to delay, justice is better served by a brief continuance, trial on the merits, and final disposition of the cases before the court.[16]

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the petition for review on certiorari is GRANTED. The March 2, 2005 Order and the May 20, 2005 Resolution of the Regional Trial Court of Iloilo City, Branch 39 in Sp. Proc. No. 5198 are REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The case is REMANDED to the court of origin for further proceedings.

SO ORDERED.

Ynares-Santiago, (Chairperson), Austria-Martinez, Chico-Nazario, and Reyes., JJ., concur.

[1] Rollo, pp. 57-58.

[2] Id. at 70.

[3] Id. at 56.

[4] Id.

[5] Sec. 3. Dismissal due to fault of plaintiff.- If, for no justifiable cause, the plaintiff fails to appear on the date of the presentation of his evidence in chief on the complaint, or to prosecute his action for an unreasonable length of time, or to comply with these Rules or any order of the court, the complaint may be dismissed upon motion of the defendant or upon the court's own motion, without prejudice to the right of the defendant to prosecute his counterclaim in the same or in a separate action. This dismissal shall have the effect of an adjudication upon the merits, unless otherwise declared by the court.

[6] The pertinent portions of the March 2, 2005 Order reads:

xxxx

To date, however, the herein parties and/or their counsel have egregiously failed to abide by the aforequoted (sic) Order of the Court to the monumental detriment of the Court's avowed goal of rendering justice with dispatch. Ineluctably, with this actuation of the parties and/or their counsel, the Court is of the gnawing impression that they have completely lost interest in the prosecution of the motions extant and/or may have already settled their differences extrajudicially which is, of course, salutary.

In view of this, and in line with the provisions of Section 3, Rule 17 of the Revised Rules of Court, the pendant motions should now be disposed of by the Court with finality.

WHEREFORE, premises duly considered, the instant motions and all their corollary and concomitant ramifications are all hereby DENIED WITH FINALITY and the proceedings in re TERMINATED.

SO ORDERED. (Supra note 1).

[7] Rollo, pp. 59-69.

[8] Id. at 70.

[9] Id. at 4-15.

[10] Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation v. Magwin Marketing Corporation, 450 Phil. 720, 738 (2003), citing Goldloop Properties, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, 212 SCRA 498, 506 (1992).

[11] Section 3(c), Rule 1 of the Rules of Court defines special proceeding as "a remedy by which a party seeks to establish a status, a right, or a particular fact;" see Vda. de Manalo v. Court of Appeals, 402 Phil. 152, 165 (2001).

[12] Dayo v. Dayo , 95 Phil. 703, 707 (1954).

[13] Supra note 5.

[14] Rollo, p. 56.

[15] Goldloop Properties, Inc. v. Court of Appeals, supra note 10. ============================================== ==============================

SECOND DIVISION

ALFREDO HILADO, LOPEZ

G.R. No. 164108

SUGAR CORPORATION, FIRST

FARMERS HOLDING

Present:

CORPORATION,

Petitioners,

CARPIO MORALES, J.,*

Acting Chairperson,

TINGA,

VELASCO, JR.,

- versus -

LEONARDO-DE CASTRO,** and

BRION, JJ.

THE HONORABLE COURT OF

APPEALS, THE HONORABLE

Promulgated:

AMOR A. REYES, Presiding Judge,

Regional Trial Court of Manila,

May 8, 2009

Branch 21 and ADMINISTRATRIX

JULITA CAMPOS BENEDICTO,

Respondents.

x----------------------------------------------------------------------------x

DECISION

Tinga, J.:

The well-known sugar magnate Roberto S. Benedicto died intestate on 15 May 2000. He was survived by his wife, private respondent Julita Campos Benedicto (administratrix Benedicto), and his only daughter, Francisca Benedicto-Paulino.[1] At the time of his death, there were two pending civil cases against Benedicto involving the petitioners. The first, Civil Case No. 959137, was then pending with the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Bacolod City, Branch 44, with petitioner Alfredo Hilado as one of the plaintiffs therein. The second, Civil Case No. 11178, was then pending with the RTC of Bacolod City, Branch 44, with petitioners Lopez Sugar Corporation and First Farmers Holding Corporation as one of the plaintiffs therein.[2]

On 25 May 2000, private respondent Julita Campos Benedicto filed with the RTC of Manila a petition for the issuance of letters of administration in her favor, pursuant to Section 6, Rule 78 of the Revised Rules of Court. The petition was raffled to Branch 21, presided by respondent Judge Amor A. Reyes. Said petition acknowledged the value of the assets of the decedent to be P5 Million, net of liabilities.[3] On 2 August 2000, the Manila RTC issued an order appointing private respondent as administrator of the estate of her deceased husband, and issuing letters of administration in her favor.[4] In January 2001, private respondent submitted an Inventory of the Estate, Lists of Personal and Real Properties, and Liabilities of the Estate of her deceased husband.[5] In the List of Liabilities attached to the inventory, private respondent included as among the liabilities, the above-mentioned two pending claims then being litigated before the Bacolod City courts.[6] Private respondent stated that the amounts of liability corresponding to the two cases as P136,045,772.50 for Civil Case No. 95-9137 and P35,198,697.40 for Civil Case No. 11178.[7] Thereafter, the Manila RTC required private respondent to submit a complete and updated inventory and appraisal report pertaining to the estate.[8]

On 24 September 2001, petitioners filed with the Manila RTC a Manifestation/Motion Ex Abundanti Cautela,[9] praying that they be furnished with copies of all processes and orders pertaining to the intestate proceedings. Private respondent opposed the manifestation/motion, disputing the personality of petitioners to intervene in the intestate proceedings of her husband. Even before the Manila RTC acted on the manifestation/motion, petitioners filed an omnibus motion praying that the Manila RTC set a deadline for the submission by private respondent of the required inventory of the decedents estate.[10] Petitioners also filed other pleadings or motions with the Manila RTC, alleging lapses on the part of private respondent in her administration of the estate, and assailing the inventory that had been submitted thus far as unverified, incomplete and inaccurate.

On 2 January 2002, the Manila RTC issued an order denying the manifestation/motion, on the ground that petitioners are not interested parties within the contemplation of the Rules of Court to intervene in the intestate proceedings.[11] After the Manila RTC had denied petitioners motion for reconsideration, a petition for certiorari was filed with the Court of Appeals. The petition argued in general that petitioners had the right to intervene in the intestate proceedings of Roberto Benedicto, the latter being the defendant in the civil cases they lodged with the Bacolod RTC.

On 27 February 2004, the Court of Appeals promulgated a decision[12] dismissing the petition and declaring that the Manila RTC did not abuse its discretion in refusing to allow petitioners to intervene in the intestate proceedings. The allowance or disallowance of a motion to intervene, according to the appellate court, is addressed to the sound discretion of the court. The Court of Appeals cited the fact that the claims of petitioners against the decedent were in fact contingent or expectant, as these were still pending litigation in separate proceedings before other courts.

Hence, the present petition. In essence, petitioners argue that the lower courts erred in denying them the right to intervene in the intestate proceedings of the estate of Roberto Benedicto. Interestingly, the rules of procedure they cite in support of their argument is not the rule on intervention, but rather various other provisions of the Rules on Special Proceedings.[13]

To recall, petitioners had sought three specific reliefs that were denied by the courts a quo. First, they prayed that they be henceforth furnished copies of all processes and orders issued by the intestate court as well as the pleadings filed by administratrix Benedicto with the said court.[14] Second, they prayed that the intestate court set a deadline for the submission by administratrix Benedicto to submit a verified and complete inventory of the estate, and upon submission thereof, order the inheritance tax appraisers of the Bureau of Internal Revenue to assist in the appraisal of the fair market value of the same.[15] Third, petitioners moved that the intestate court set a deadline for the submission by the administrator of her verified annual account, and, upon submission thereof, set the date for her examination under oath with respect thereto, with due notice to them and other parties interested in the collation, preservation and disposition of the estate.[16]

The Court of Appeals chose to view the matter from a perspective solely informed by the rule on intervention. We can readily agree with the Court of Appeals on that point. Section 1 of Rule 19 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure requires that an intervenor has a legal interest in the matter in litigation, or in the success of either of the parties, or an interest against both, or is so situated as to be adversely affected by a distribution or other disposition of property in the custody of the court x x x While the language of Section 1, Rule 19 does not literally preclude petitioners from intervening in the intestate proceedings, case law has consistently held that the legal interest required of an intervenor must be actual and material, direct and immediate, and not simply contingent and expectant.[17]

Nonetheless, it is not immediately evident that intervention under the Rules of Civil Procedure necessarily comes into operation in special proceedings. The settlement of estates of deceased persons fall within the rules of special proceedings under the Rules of Court,[18] not the Rules on Civil Procedure. Section 2, Rule 72 further provides that [i]n the absence of special provisions, the rules provided for in ordinary actions shall be, as far as practicable, applicable to special proceedings.

We can readily conclude that notwithstanding Section 2 of Rule 72, intervention as set forth under Rule 19 does not extend to creditors of a decedent whose credit is based on a contingent claim. The definition of intervention under Rule 19 simply does not accommodate contingent claims.

Yet, even as petitioners now contend before us that they have the right to intervene in the intestate proceedings of Roberto Benedicto, the reliefs they had sought then before the RTC, and also now before us, do not square with their recognition as intervenors. In short, even if it were declared that petitioners have no right to intervene in accordance with Rule 19, it would not necessarily mean the disallowance of the reliefs they had sought before the RTC since the right to intervene is not one of those reliefs.

To better put across what the ultimate disposition of this petition should be, let us now turn our focus to the Rules on Special Proceedings.

In several instances, the Rules on Special Proceedings entitle any interested persons or any persons interested in the estate to participate in varying capacities in the testate or intestate proceedings. Petitioners cite these provisions before us, namely: (1) Section 1, Rule 79, which recognizes the right of any person interested to oppose the issuance of letters testamentary and to file a petition for administration; (2) Section 3, Rule 79, which mandates the giving of notice of hearing on the petition for letters of administration to the known heirs, creditors, and to any other persons believed to have interest in the estate; (3) Section 1, Rule 76, which allows a person interested in the estate to petition for the allowance of a will; (4) Section 6 of Rule 87, which allows an individual interested in the estate of the deceased to complain to the court of the concealment, embezzlement, or conveyance of any asset of the decedent, or of evidence of the decedents title or interest therein; (5) Section 10 of Rule 85, which requires notice of the time and place of the examination and allowance of the Administrators

account to persons interested; (6) Section 7(b) of Rule 89, which requires the court to give notice to the persons interested before it may hear and grant a petition seeking the disposition or encumbrance of the properties of the estate; and (7) Section 1, Rule 90, which allows any person interested in the estate to petition for an order for the distribution of the residue of the estate of the decedent, after all obligations are either satisfied or provided for.

Had the claims of petitioners against Benedicto been based on contract, whether express or implied, then they should have filed their claim, even if contingent, under the aegis of the notice to creditors to be issued by the court immediately after granting letters of administration and published by the administrator immediately after the issuance of such notice.[19] However, it appears that the claims against Benedicto were based on tort, as they arose from his actions in connection with Philsucom, Nasutra and Traders Royal Bank. Civil actions for tort or quasi-delict do not fall within the class of claims to be filed under the notice to creditors required under Rule 86.[20] These actions, being as they are civil, survive the death of the decedent and may be commenced against the administrator pursuant to Section 1, Rule 87. Indeed, the records indicate that the intestate estate of Benedicto, as represented by its administrator, was successfully impleaded in Civil Case No. 11178, whereas the other civil case[21] was already pending review before this Court at the time of Benedictos death.

Evidently, the merits of petitioners claims against Benedicto are to be settled in the civil cases where they were raised, and not in the intestate proceedings. In the event the claims for damages of petitioners are granted, they would have the right to enforce the judgment against the estate. Yet until such time, to what extent may they be allowed to participate in the intestate proceedings?

Petitioners place heavy reliance on our ruling in Dinglasan v. Ang Chia, [22] and it does provide us with guidance on how to proceed. A brief narration of the facts therein is in order. Dinglasan had filed an action for reconveyance and damages against respondents, and during a hearing of the case, learned that the same trial court was hearing the intestate proceedings of Lee Liong to whom Dinglasan had sold the property years earlier. Dinglasan thus amended his complaint to implead Ang Chia, administrator of the estate of her late husband. He likewise filed a verified claim-inintervention, manifesting the pendency of the civil case, praying that a coadministrator be appointed, the bond of the administrator be increased, and that the intestate proceedings not be closed until the civil case had been terminated. When the trial court ordered the increase of the bond and took cognizance of the pending civil case, the administrator moved to close the intestate proceedings, on the ground that the heirs had already entered into an extrajudicial partition of the estate. The trial court refused to close the intestate proceedings pending the termination of the civil case, and the Court affirmed such action.

If the appellants filed a claim in intervention in the intestate proceedings it was only pursuant to their desire to protect their interests it appearing that the property in litigation is involved in said proceedings and in fact is the only property of the estate left subject of administration and distribution; and the court is justified in taking cognizance of said civil case because of the unavoidable fact that whatever is determined in said civil case will necessarily reflect and have a far reaching consequence in the determination and distribution of the estate. In so taking cognizance of civil case No. V-331 the court does not assume general jurisdiction over the case but merely makes of record its existence because of the close interrelation of the two cases and cannot therefore be branded as having acted in excess of its jurisdiction.

Appellants' claim that the lower court erred in holding in abeyance the closing of the intestate proceedings pending determination of the separate

civil action for the reason that there is no rule or authority justifying the extension of administration proceedings until after the separate action pertaining to its general jurisdiction has been terminated, cannot be entertained. Section 1, Rule 88, of the Rules of Court, expressly provides that "action to recover real or personal property from the estate or to enforce a lien thereon, and actions to recover damages for an injury to person or property, real or personal, may be commenced against the executor or administrator." What practical value would this provision have if the action against the administrator cannot be prosecuted to its termination simply because the heirs desire to close the intestate proceedings without first taking any step to settle the ordinary civil case? This rule is but a corollary to the ruling which declares that questions concerning ownership of property alleged to be part of the estate but claimed by another person should be determined in a separate action and should be submitted to the court in the exercise of its general jurisdiction. These rules would be rendered nugatory if we are to hold that an intestate proceedings can be closed by any time at the whim and caprice of the heirs x x x[23] (Emphasis supplied) [Citations omitted]

It is not clear whether the claim-in-intervention filed by Dinglasan conformed to an action-in-intervention under the Rules of Civil Procedure, but we can partake of the spirit behind such pronouncement. Indeed, a few years later, the Court, citing Dinglasan, stated: [t]he rulings of this court have always been to the effect that in the special proceeding for the settlement of the estate of a deceased person, persons not heirs, intervening therein to protect their interests are allowed to do so to protect the same, but not for a decision on their action.[24]

Petitioners interests in the estate of Benedicto may be inchoate interests, but they are viable interests nonetheless. We are mindful that the Rules of Special Proceedings allows not just creditors, but also any person interested or persons interested in the estate various specified capacities to protect their respective interests in the estate. Anybody with a contingent claim based on a pending action for quasi-delict against a decedent may be reasonably concerned that by the time judgment is rendered in their favor, the estate of the decedent would have already been distributed, or diminished to the extent that the judgment could no longer be enforced against it.

In the same manner that the Rules on Special Proceedings do not provide a creditor or any person interested in the estate, the right to participate in every aspect of the testate or intestate proceedings, but instead provides for specific instances when such persons may accordingly act in those proceedings, we deem that while there is no general right to intervene on the part of the petitioners, they may be allowed to seek certain prayers or reliefs from the intestate court not explicitly provided for under the Rules, if the prayer or relief sought is necessary to protect their interest in the estate, and there is no other modality under the Rules by which such interests can be protected. It is under this standard that we assess the three prayers sought by petitioners.

The first is that petitioners be furnished with copies of all processes and orders issued in connection with the intestate proceedings, as well as the pleadings filed by the administrator of the estate. There is no questioning as to the utility of such relief for the petitioners. They would be duly alerted of the developments in the intestate proceedings, including the status of the assets of the estate. Such a running account would allow them to pursue the appropriate remedies should their interests be compromised, such as the right, under Section 6, Rule 87, to complain to the intestate court if property

of the estate concealed, embezzled, or fraudulently conveyed.

At the same time, the fact that petitioners interests remain inchoate and contingent counterbalances their ability to participate in the intestate proceedings. We are mindful of respondents submission that if the Court were to entitle petitioners with service of all processes and pleadings of the intestate court, then anybody claiming to be a creditor, whether contingent or otherwise, would have the right to be furnished such pleadings, no matter how wanting of merit the claim may be. Indeed, to impose a precedent that would mandate the service of all court processes and pleadings to anybody posing a claim to the estate, much less contingent claims, would unduly complicate and burden the intestate proceedings, and would ultimately offend the guiding principle of speedy and orderly disposition of cases.

Fortunately, there is a median that not only exists, but also has been recognized by this Court, with respect to the petitioners herein, that addresses the core concern of petitioners to be apprised of developments in the intestate proceedings. In Hilado v. Judge Reyes,[25] the Court heard a petition for mandamus filed by the same petitioners herein against the RTC judge, praying that they be allowed access to the records of the intestate proceedings, which the respondent judge had denied from them. Section 2 of Rule 135 came to fore, the provision stating that the records of every court of justice shall be public records and shall be available for the inspection of any interested person x x x. The Court ruled that petitioners were interested persons entitled to access the court records in the intestate proceedings. We said:

Petitioners' stated main purpose for accessing the records tomonitor prompt compliance with the Rules governing the preservation and proper disposition of the assets of the estate, e.g., the completion and appraisal of the Inventory and the submission by the Administratrix of an annual accountingappears legitimate, for, as the plaintiffs in the complaints for sum of money against Roberto Benedicto, et al., they have an interest over

the outcome of the settlement of his estate. They are in fact "interested persons" under Rule 135, Sec. 2 of the Rules of Court x x x[26]

Allowing creditors, contingent or otherwise, access to the records of the intestate proceedings is an eminently preferable precedent than mandating the service of court processes and pleadings upon them. In either case, the interest of the creditor in seeing to it that the assets are being preserved and disposed of in accordance with the rules will be duly satisfied. Acknowledging their right to access the records, rather than entitling them to the service of every court order or pleading no matter how relevant to their individual claim, will be less cumbersome on the intestate court, the administrator and the heirs of the decedent, while providing a viable means by which the interests of the creditors in the estate are preserved.

Nonetheless, in the instances that the Rules on Special Proceedings do require notice to any or all interested parties the petitioners as interested parties will be entitled to such notice. The instances when notice has to be given to interested parties are provided in: (1) Sec. 10, Rule 85 in reference to the time and place of examining and allowing the account of the executor or administrator; (2) Sec. 7(b) of Rule 89 concerning the petition to authorize the executor or administrator to sell personal estate, or to sell, mortgage or otherwise encumber real estates; and; (3) Sec. 1, Rule 90 regarding the hearing for the application for an order for distribution of the estate residue. After all, even the administratrix has acknowledged in her submitted inventory, the existence of the pending cases filed by the petitioners.

We now turn to the remaining reliefs sought by petitioners; that a deadline be set for the submission by administratrix Benedicto to submit a verified and complete inventory of the estate, and upon submission thereof: the inheritance tax appraisers of the Bureau of Internal Revenue be required to assist in the appraisal of the fair market value of the same; and that the intestate court set a deadline for the submission by the administratrix of her ve= ============================================== ==============

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 144915

February 23, 2004

CAROLINA CAMAYA, FERDINAND CAMAYA, EDGARDO CAMAYA and ANSELMO MANGULABNAN, petitioners vs. BERNARDO PATULANDONG, respondent.

DECISION

CARPIO-MORALES, J.:

Before this Court is a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the 1997 Revised Rules of Court seeking the reversal of the Court of Appeals Decision dated June 19, 2000 in CA-G.R. CV No. 53757, "In re: Petition for the Probate of the Codicil (Will) of Rufina Reyes; Bernardo Patulandong v. Anselmo Mangulabnan v. Carolina G. Camaya, Ferdinand Camaya and Edgardo Camaya."

On November 17, 1972, Rufina Reyes (testatrix) executed a notarized will wherein she devised, among others, Lot No. 288-A to her grandson Anselmo Mangulabnan (Mangulabnan). The pertinent portion of her will reads:

IKALIMA. - Aking inihahayag at ginagawa na tagapagmana, sa aking kusang loob, ang pinalaki kong APO na si ANSELMO P. MANGULABNAN, may sapat na gulang, kasal kay Flora Umagap, at naninirahan sa San Lorenzo, Gapan, Nueva Ecija, at anak ng aking anak na si SIMPLICIA, at sa aking APO na si ANSELMO ay aking ipinagkakaloob at ipinamamana, sa aking pagkamatay, ang mga sumusunod kong pagaari: LOT NO. TITLE NO. KINALALAGYAN NABANGGIT SA

288-A NT-47089 3348-A 3349-B

Sta. Cruz (1) p. 2 Poblacion (2) p. 2 Poblacion (3) p. 2

100629 100630

xxx1 (Underscoring in the original; emphasis supplied)

The testatrixs son Bernardo Patulandong (Patulandong), respondent herein, was in the will appointed as the executor.

During her lifetime, the testatrix herself filed a petition for the probate of her will before the then Court of First Instance (CFI) of Nueva Ecija where it was docketed as Sp. Pro. No. 128.

By Order2 of January 11, 1973, the CFI admitted the will to probate.

On June 27, 1973, the testatrix executed a codicil modifying above-quoted paragraph five of her will in this wise:

UNA. - Ang Lote No. 288-A na nakalagay sa barrio ng Sta. Cruz, Gapan, Nueva Ecija, magsukat 36,384 metro cuadrados, at nagtataglay ng TCT No. NT47089, na aking ipinamana sa aking apong si ANSELMO P. MANGULABNAN, sangayon sa Pangkat IKA-LIMA, pp. 5-6, ng aking HULING HABILIN (Testamento), ay ipinasiya kong ipagkaloob at ipamana sa aking mga anak na sina BERNARDO, SIMPLICIA, GUILLERMA at JUAN nagaapellidong PATULANDONG, at sa aking apong si ANSELMO P. MANGULABNAN, sa magkakaparehong bahagi na tig-ikalimang bahagi bawat isa sa kanila.

IKALAWA. - Na maliban sa pagbabagong ito, ang lahat ng mga tadhana ng aking HULING HABILIN ay aking pinagtitibay na muli.

x x x3 (Underscoring in the original; emphasis supplied) On May 14, 1988, the testatrix died.

Mangulabnan later sought the delivery to him by executor Patulandong of the title to Lot 288-A. Patulandong refused to heed the request, however, in view of the codicil which modified the testators will.

Mangulabnan thus filed an "action for partition" against Patulandong with the Regional Trial Court of Gapan, Nueva Ecija, docketed as Civil Case No. 552 (the partition case).

On June 8, 1989, the trial court rendered a decision in the partition case,4 the dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, the court orders the partitioning of the properties and the defendant to deliver the copy of the Transfer Certificate of Title No. NT47089.

However, in view of the case cited by the plaintiff himself, the court holds that the partition is without prejudice [to]... the probate of the codicil in accordance with the Rules of Court, [P]alacios vs. Catimbang Palacios cited by the plaintiff:

"After a will has been probated during the lifetime of the testator, it does not necessarily mean that he cannot alter or revoke the same before his death. Should he make a new will, it would also be allowable of his petition and if he should die before he had a chance to present such petition, the ordinary probate proceedings after the testators death would be in order."

The Court also orders that the right of the tenants of the agricultural land in question should be protected meaning to say that the tenants should not be ejected. (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

On July 17, 1989 Patulandong filed before the Regional Trial Court of Nueva Ecija a petition5 for probate of the codicil of the testatrix, docketed as Sp. Proc. No. 218.

On December 28, 1989, the probate court issued an Order6 setting the petition for hearing and ordering the publication of said order.

On February 7, 1991, by virtue of the decision in the partition case, Mangulabnan caused the cancellation of the title of the testatrix over Lot No. 288-A and TCT No. NT-2157507 was issued in his name.

Mangulabnan later sold to herein petitioners Camayas Lot No. 288-A by a Deed of Sale dated February 19, 1991.8 TCT No. NT-215750 was thus cancelled and TCT No. NT-2164469 was issued in the name of the Camayas.

On January 16, 1996, the trial rendered a decision10 in Sp. Proc. No. 218 admitting the codicil to probate and disposing as follows:

WHEREFORE, in view of all the foregoing, judgment is hereby rendered in the following manner:

1. Declaring Transfer Certificate of Title No. NT-215750 issued by the Register of Deeds of Nueva Ecija in the name of Anselmo Mangulabnan dated February 7, 1991 and the Deed of Absolute Sale executed by him in favor of the intervenors Carolina, Ferdinand and Edgardo, all surnamed Camaya on February 19, 1991 and Transfer Certificate of Title No. NT-216446 under date March 18, 1991 issued in the names of the above-named intervenors as NULL and VOID and of no force and effect; and,

2. Ordering the Register of Deeds of Nueva Ecija to cancel Transfer of Certificate of Title Nos. NT-215750 and NT-216446 and reissue the corresponding Certificate of Titles to Bernardo R. Patulandong, Filipino, married to Gorgonia Mariano residing at San Vicente, Gapan, Nueva Ecija, Juan R. Patulandong, Filipino, widower and residing at San Lorenzo, Gapan, Nueva Ecija; Guillerma R. Patulandong Linsangan of legal age, Filipino, widow and residing at San Vicente, Gapan, Nueva Ecija, Simplicia R. Patulandong Mangulabnan, of legal age, widow, and residing at San Lorenzo, Gapan, Nueva Ecija and her grandson, Anselmo Mangulabnan with full personal circumstances stated herein to the extent of one fifth (1/5) each pursuant to the approved codicil (will) of Rufina Reyes dated June 27, 1973.11

The Camayas who had been allowed to intervene in Sp. Proc. No. 218, and Mangulabnan, filed a Motion for Reconsideration of the above-said decision but it was denied by Order12 of February 28,1996.

On appeal to the Court of Appeals, the Camayas and Mangulabnan (hereinafter referred to as petitioners) raised the following errors:

1. THERE WERE SERIOUS SUBSTANTIAL DEPARTURES FROM THE FORMALITIES REQUIRED BY THE RULES, THE LAW, AND THE AUTHORITY OF THE REGIONAL TRIAL COURT SETTING AS A PROBATE COURT.

2. THE OPPOSITOR DID NOT ONLY ACQUIRE LOT NO. 288-A BY WILL BUT HE ALSO ACQUIRED THE SAME BY PARTITION IN A CIVIL CASE WHERE THE DECISION HAS ALREADY REACHED ITS FINALITY AND THEREFORE CAN NO LONGER BE NEGATED BY A QUESTIONABLE CODICIL.

3. THAT THE SUBJECT LOT 288-A IS NO LONGER WITHIN THE REACHED (sic) OF THE PETITIONER CONSIDERING THAT THE OPPOSITOR VENDOR HAD A CLEAN TITLE AND THAT THE INTERVENORS-VENDEED HAD ACQUIRED THE SAME BY WAY OF SALE AS INNOCENT PURCHASER IN GOOD FAITH AND FOR VALUE.13

By Decision14 of June 19, 2000, the Court of Appeals affirmed that of the trial court.

Hence, the present petition for Review on Certiorari proffering the following issues:

1. Whether the probate court exceeded its jurisdiction when it declared null and void and ordered the cancellation of the TCTs of petitioners and the deed of sale; and

2. Whether the final judgment in Civil Case No. 552 bars the allowance of the codicil.

As to the first issue, petitioners contend that the under the law, the probate court has no power, authority, and jurisdiction to declare null and void the sale and titles of petitioners;15 and that the probate court can only resolve the following issues:

1. Whether or not the instrument which is offered for probate is the last will and testament of the decedent; in other words, the question is one of identity[;]

2. Whether or not the will has been executed in accordance with the formalities prescribed by law; in other words, the question is one of due execution[; and]

3. Whether the testator had testamentary capacity at the time of the execution of the will; in other words, the question is one of capacity.16

In Cuizon v. Ramolete, 17 this Court elucidated on the limited jurisdiction of a probate court, to wit:

It is well-settled rule that a probate court or one in charge of proceedings whether testate or intestate cannot adjudicate or determine title to properties claimed to be a part of the estate and which are equally claimed to belong to outside parties. All that said court could do as regards said properties is to determine whether they should or should not be included in the inventory or list of properties to be administered by the administrator. If there is no dispute, well and good; but if there is, then the parties, the administrator, and the opposing parties have to resort to an ordinary action for a final determination of the conflicting claims of title because the probate court cannot do so.

xxx

Having been apprised of the fact that the property in question was in the possession of third parties and more important, covered by a transfer certificate of title issued in the name of such third parties, the respondent court should have denied the motion of the respondent administrator and excluded the property in question from the inventory of the property of the estate. It had no authority to deprive such third persons of their possession and ownership of the property. x x x (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Following Cuizon, the probate court exceeded its jurisdiction when it further declared the deed of sale and the titles of petitioners null and void, it having had the effect of depriving them possession and ownership of the property.

Moreover, following Section 48 of the Property Registry Decree which reads:

SECTION 48. Certificate not subject to collateral attack. - A certificate of title shall not be subject to collateral attack. It cannot be altered, modified, or cancelled except in a direct proceeding in accordance with law,

petitioners titles cannot, under probate proceedings, be declared null and void.

As to the second issue, petitioners argue that by allowing the codicil to probate, it in effect amended the final judgment in the partition case which is not allowed by law;18 and that petitioner Camayas are innocent purchasers for value and enjoy the legal presumption that the transfer was lawful.19

Petitioners first argument does not persuade.

Though the judgment in the partition case had become final and executory as it was not appealed, it specifically provided in its dispositive portion that the decision was "without prejudice [to] ... the probate of the codicil." The rights of the prevailing parties in said case were thus subject to the outcome of the probate of the codicil.

The probate court being bereft of authority to rule upon the validity of petitioners titles, there is no longer any necessity to dwell on the merits of petitioners Camayas claim that they are innocent purchasers for value and enjoy the legal presumption that the transfer was lawful.

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED IN PART.

The Decision of the Court of Appeals dated June 19, 2000 in CA-G.R. CV No. 53757 affirming the January 16, 1996 Decision of Regional Trial Court, Branch

35, of Gapan, Nueva Ecija, is hereby AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION.

The decision allowing the codicil is AFFIRMED, but the 1) declaration as null and void of Transfer Certificate of Title No. NT-215750 issued on February 7, 1991 by the Register of Deeds of Nueva Ecija in the name of Anselmo Mangulabnan, the February 19, 1991 Deed of Absolute Sale executed by him in favor of the intervenors - herein petitioners Carolina, Ferdinand and Edgardo Camaya, and Transfer Certificate of Title No. NT-216446 issued on March 18, 1991 in favor of the petitioners Camayas, and 2) the order for the Register of Deeds of Nueva Ecija to cancel Transfer of Certificate of Title Nos. NT-215750 and NT-216446 and reissue the corresponding Certificate of Titles to Bernardo R. Patulandong, Juan R. Patulandong, Guillerma R. Patulandong Linsangan, Simplicia R. Patulandong Mangulabnan, and Anselmo Mangulabnan to the extent of one-fifth (1/5) each pursuant to the approved codicil are SET ASIDE, without prejudice to respondent and his co-heirs ventilation of their right in an appropriate action.

SO ORDERED.

Vitug, (Chairman), Sandoval-Gutierrez, and Corona, JJ., concur.

Footnotes

1 Records at 9-10.

2 Id. at 13-14. ============================================== ======================= THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 127920. August 9, 2005

EMILIO B. PACIOLES, JR., IN HIS CAPACITY AS ADMINISTRATOR AND HEIR OF THE INTESTATE ESTATE OF MIGUELITA CHING-PACIOLES, Petitioner, vs. MIGUELA CHUATOCO-CHING, Respondent.

DECISION

SANDOVAL-GUTIERREZ, J.:

Oftentimes death brings peace only to the person who dies but not to the people he leaves behind. For in death, a person's estate remains, providing a fertile ground for discords that break the familial bonds. Before us is another case that illustrates such reality. Here, a husband and a mother of the deceased are locked in an acrimonious dispute over the estate of their loved one.

This is a petition for review on certiorari filed by Emilio B. Pacioles, Jr., herein petitioner, against Miguela Chuatoco-Ching, herein respondent, assailing the Court of Appeals Decision[1] dated September 25, 1996 and Resolution[2] dated January 27, 1997 in CA-G.R. SP No. 41571.[3] The Appellate Court affirmed the Order dated January 17, 1996 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC), Branch 99, Quezon City denying petitioner's motion for partition and distribution of the estate of his wife, Miguelita Ching-Pacioles; and his motion for reconsideration.

The facts are undisputed.

On March 13, 1992, Miguelita died intestate, leaving real properties with an estimated value of P10.5 million, stock investments worth P518,783.00, bank deposits amounting to P6.54 million, and interests in certain businesses. She was survived by her husband, petitioner herein, and their two minor children.

Consequently, on August 20, 1992, petitioner filed with the RTC a verified petition[4] for the settlement of Miguelita's estate. He prayed that (a) letters of administration be issued in his name, and (b) that the net residue of the

estate be divided among the compulsory heirs.

Miguelita's mother, Miguela Chuatoco-Ching, herein respondent, filed an opposition, specifically to petitioner's prayer for the issuance of letters of administration on the grounds that (a) petitioner is incompetent and unfit to exercise the duties of an administrator; and (b) the bulk of Miguelita's estate is composed of 'paraphernal properties. Respondent prayed that the letters of administration be issued to her instead.[5] Afterwards, she also filed a motion for her appointment as special administratrix.[6]

Petitioner moved to strike out respondent's opposition, alleging that the latter has no direct and material interest in the estate, she not being a compulsory heir, and that he, being the surviving spouse, has the preferential right to be appointed as administrator under the law.[7]

Respondent countered that she has direct and material interest in the estate because she gave half of her inherited properties to Miguelita on condition that both of them 'would undertake whatever business endeavor they decided to, in the capacity of business partners.[8]

In her omnibus motion[9] dated April 23, 1993, respondent nominated her son Emmanuel Ching to act as special administrator.

On April 20, 1994, the intestate court issued an order appointing petitioner and Emmanuel as joint regular administrators of the estate.[10] Both were issued letters of administration after taking their oath and posting the requisite bond.

Consequently, Notice to Creditors was published in the issues of the Standard on September 12, 19, and 26, 1994. However, no claims were filed against the estate within the period set by the Revised Rules of Court.

Thereafter, petitioner submitted to the intestate court an inventory of Miguelita's estate.[11] Emmanuel did not submit an inventory.

On May 17, 1995, the intestate court declared petitioner and his two minor children as the only compulsory heirs of Miguelita.[12]

On July 21, 1995, petitioner filed with the intestate court an omnibus motion[13] praying, among others, that an Order be issued directing the: 1) payment of estate taxes; 2) partition and distribution of the estate among the declared heirs; and 3) payment of attorney's fees.

Respondent opposed petitioner's motion on the ground that the partition and distribution of the estate is 'premature and precipitate, considering that there is yet no determination 'whether the properties specified in the inventory are conjugal, paraphernal or owned in a joint venture.[14] Respondent claimed that she owns the bulk of Miguelita's estate as an 'heir and co-owner. Thus, she prayed that a hearing be scheduled.

On January 17, 1996, the intestate court allowed the payment of the estate taxes and attorney's fees but denied petitioner's prayer for partition and distribution of the estate, holding that it is indeed 'premature. The intestate court ratiocinated as follows:

On the partition and distribution of the deceased's properties, among the declared heirs, the Court finds the prayer of petitioner in this regard to be premature. Thus, a hearing on oppositor's claim as indicated in her opposition to the instant petition is necessary to determine 'whether the properties listed in the amended complaint filed by petitioner are entirely conjugal or the paraphernal properties of the deceased, or a co-ownership between the oppositor and the petitioner in their partnership venture.

Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration but it was denied in the Resolution dated May 7, 1996.

Forthwith, petitioner filed with the Court of Appeals a petition for certiorari seeking to annul and set aside the intestate court's Order dated January 17, 1996 and Resolution dated May 7, 1996 which denied petitioner's prayer for

partition and distribution of the estate for being premature, indicating that it (intestate court) will first resolve respondent's claim of ownership.