Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cholecystectomy

Încărcat de

Rachelle Maderazo CartinDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cholecystectomy

Încărcat de

Rachelle Maderazo CartinDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cartin, Rachelle M.

BSN IV A2 Group Ca5

Mrs. Sarmiento Ospital ng Sampaloc

Cholecystectomy

Cholecystectomy is the surgical removal of the gallbladder, which is located in the abdomen beneath the right side of the liver. Gallbladder problems are usually the result of gallstones. These stones may block the flow of bile from your gallbladder, causing the organ to swell. Other causes include cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder) and cholangitis (inflammation of the bile duct). Anatomy and Physiology The gall bladder is a small pear shaped organ located beneath the liver in the right side of the upper abdomen.

The cystic duct carries bile from the gallbladder and joins the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct. The common bile duct then empties into the beginning of the small intestine. The main purpose of the gallbladder is to concentrate and store bile. It releases bile by ejecting it through the common bile duct into the small intestine when fatty foods are eaten. The bile aids in the digestion of fatty foods. However, one can live without the gallbladder without suffering symptoms. Pathology Stones may form in the gall bladder, which block the flow of bile resulting in pain in the right upper abdomen. Gallstones can lodge in the terminal part of the common bile duct that opens into the small intestine. Here the stones can also block the flow of pancreatic juice from the pancreatic duct that joins the common bile duct. This may result in a severe inflammation of the pancreas called pancreatitis. The exact cause of gall bladder disease is unknown. Some studies suggest that gallstones may be related to how the body handles cholesterol

and bile acids that are synthesized in the liver and stored in the gall bladder. While some people may have no symptoms even in the presence of gallstones, others may have gallbladder problems even in the absence of stones. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

y y

y y y y y

Today, the standard of care is usually a laparoscopic cholecystectomy The laparoscope is a long tube with lenses at one end that are connected by fiber optics to a small television camera at the other. The fiber optics also carries light into the abdomen from a special light source. This system allows the surgeon to see and operate within the abdomen The procedure is usually performed under general anesthesia Antibiotics are given intravenously prior to the surgery to reduce the rate of infection After anesthesia is begun, the skin is prepared with antiseptic solution and 3-4 small incisions (called port sites) are made on the abdominal wall A special needle (Veress needle) is inserted into the abdomen to inflate the abdomen with carbon dioxide gas. This distends the abdomen and creates space to insert the instruments The laparoscope and laparoscopic instruments with long handles are inserted through the incisions into the abdomen. The entire operation is then performed while viewing the organs magnified on a television screen The gallbladder is dissected off the surrounding structures. The cystic duct that attaches the gallbladder to the common bile duct is dissected and divided between metal clips In some cases, a tiny catheter may be inserted into the cystic duct to inject dye and take X-rays to visualize any stones that may be blocking the common bile duct. If common bile duct stones are present, they may be removed with laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, by opening up the abdomen and exploring the duct or by ERCP (see below) After the cystic duct is divided, the gallbladder is further dissected off the liver bed and a tiny artery that supplies blood to the gallbladder called the cystic artery is divided between metal clips. The gallbladder is then further dissected off the liver avoiding spillage of bile into the abdominal cavity In some cases, the gallbladder is shrunk by suctioning out bile. The gallbladder is then removed through one of the ports in the abdominal wall and the tiny incisions in the abdominal wall are closed after removing any gas left in the abdominal cavity. When there is spillage of bile, the local abdominal cavity is thoroughly cleansed with saline solution and a small drain may be left in place. This may be removed the same evening or the next day, when drainage ceases

y y

ERCP

y y y

y y

ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-Pancreatography) is a procedure usually performed by an endoscopist. This procedure is useful when a stone obstructs the common bile duct The common bile duct is approached using a special endoscope inserted through the stomach and small intestine to the entrance of the common bile duct An X-ray study of the common bile duct is performed using a dye. A papillotomy (cutting the muscle of the lowest portion of the common bile duct) is performed to enlarge the duct opening and facilitate stone removal A small catheter and instruments may be passed into the duct to remove the stones A small catheter will occasionally be left in the duct for temporary drainage

Complications The incidence of complications after cholecystectomy is relatively low.

y y y y y y y y y

Complications of a general anesthetic, Postoperative bleeding Injury to the bile ducts or right hepatic artery Biliary leak Wound infection Injury to other abdominal organs Pulmonary embolism Deep vein thrombosis Respiratory or urinary infections

After Surgery The patient usually has minimal pain that is well controlled with medication. Frequently, patients are discharged home on the same evening after laparoscopic cholecystectomy or the next day morning with a prescription for pain medication. Patients eat a normal light diet on the day after surgery and may be able to return to light work in 3-4 days. It is preferable to avoid exertion and heavy work for a several weeks though one can take regular walks.

Cartin, Rachelle M. BSN IV A2 Group CA5

Study Documents Wrong-Site, Wrong-Patient Procedure Errors ScienceDaily (Oct. 18, 2010) Data from one liability insurance database in Colorado indicate that wrong-site and wrong-patient surgical and procedure errors continued to occur despite nationwide steps to help prevent them, according to a report in the October issue of Archives of Surgery, one of the JAMA/Archives journals. "Any intervention involving a wrong site, wrong patient or wrong procedure represents an unacceptable surgical complication, classified as a 'never event' by the National Quality Forum," the authors write as background information in the article. In 2004, the Joint Commission introduced a Universal Protocol for all accredited hospitals, ambulatory care facilities and office-based surgical facilities. "The Universal Protocol consists of three distinct parts: a preprocedure verification, a surgical site marking and a 'time-out' performed immediately before the surgical procedure. Despite the widespread implementation of the Universal Protocol in recent years, wrong-site surgery continues to pose a significant challenge to patient safety in the United States." Philip F. Stahel, M.D., of Denver Health Medical Center and University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, and colleagues analyzed data from one company that provides professional liability coverage to 6,000 practicing physicians in Colorado. Clinicians receive incentives for early reporting of adverse events and assistance for disclosure and resolution with patients and their families. In the database of 27,370 clinician-reported adverse events occurring between January 2002 and June 2008, 25 wrong-patient and 107 wrong-site procedures were identified. Five wrong-patient procedures (20 percent) and 38 wrong-site procedures (35.5 percent) resulted in significant harm to patients. One patient (0.9 percent) died after a wrong-site procedure. The researchers assessed patient narratives associated with each event and determined the root cause. For wrong-patient procedures, errors in diagnosis contributed to 56 percent of cases and errors in communication to 100 percent. Eighty-five percent of wrong-site procedures were related to errors in judgment and 72 percent to a lack of performing a "time-out." Internal medicine specialists were associated with 24 percent of wrong-patient procedures, whereas 8 percent each involved clinicians in family or general practice, pathology, urology, obstetrics-gynecology and pediatrics. Wrong-site occurrences involved specialists in orthopedic surgery (22.4 percent), general surgery (16.8 percent) and anesthesiology (12.1 percent). "The findings from the present study emphasize a continuing and concerning occurrence of wrong-site and wrong-patient procedures in the current era of the Universal Protocol, leading to frequent patient harm and rarely, patient death," the authors write. "Shockingly, non-surgical disciplines equally contribute to patient injuries related to wrong-site procedures."

"Inadequate planning of procedures and the lack of adherence to the time-out concept are the major determinants of adverse outcome. On the basis of these findings, a strict adherence to the Universal Protocol must be expanded to non-surgical specialties to achieve a zero-tolerance philosophy for these preventable incidents." Reaction:

All health care professionals involved in performing invasive proceduresas well as the patient must be actively involved in ensuring correct surgical and intervention procedures. Team training with its explicit knowledge, skills, and attitudes required of the full surgical team, including the clerical scheduling personnel,nurses, surgeons, and anesthesiologistsshould be required in health care facilities. The "time out should occur when the patient arrives in the operating room and before they are moved from their bed to the operating table. All members of the operating room team must cease all activity and focus their attention on the patient. The first member of the team presents their pertinent information relating to the ensuing surgical procedure. The anesthesiologist or the surgeon usually begins by identifying the patient employing at least two identifiers. Usually, these are the patient's name and medical record number confirmed by the patients themselves, if possible, and by identifying the medical record numbers on the patient's wrist band with that on their chart and identification card. If the surgeon starts, he or she states the type of surgery to be performed and the site of the surgery which has already been marked prior to entering the O.R. Next, he or she announces that all the equipment necessary for the procedure is present and that the patient is in the correct position so that the surgery may be performed without difficulty. The anesthesiologist then announces the type of anesthetic, confirms the position in which the patient will be placed, the padding of the patient to prevent injury while under the effects of anesthesia, medications administered to the patient prior to entering the operating room, and the monitors to be employed to measure the patient's vital signs with emphasis on maintaining the patient's temperature as close to normal as possible. The cascade reporting continues until all involved in the surgery have voiced their respective obligations or concerns. After this, the patient is moved to the operating room table and the anesthetic begins. This very simple process, which takes minutes, has already reduced errors and inefficiencies such as operating on the wrong patient, the wrong type of surgery being performed, the wrong surgical site, medication allergies, and leaving surgical instruments in a patient. Although the above mistakes do not commonly occur, when they do, the results can be catastrophic.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- CholecystectomyDocument5 paginiCholecystectomydkbjÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study CLD 1Document12 paginiCase Study CLD 1MoonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cholecystitis (Case Presentation)Document50 paginiCholecystitis (Case Presentation)Gregory Litang60% (10)

- CHOLEDOCHOLITHIASISDocument38 paginiCHOLEDOCHOLITHIASISPrecious Cofreros100% (3)

- Case Study - Gallbladder Hydrops Calculus CholecystitisDocument22 paginiCase Study - Gallbladder Hydrops Calculus CholecystitisAice Ken0% (2)

- Case StudyDocument21 paginiCase StudyLuige AvilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electrolyte ImbalanceDocument76 paginiElectrolyte ImbalanceSarah Racheal Akello100% (2)

- Digital Rectal ExaminationDocument17 paginiDigital Rectal Examinationyulianpatriawan100% (2)

- Final EditDocument43 paginiFinal EditMary Rose LinatocÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study Presented by Group 22 BSN 206: In-Depth View On CholecystectomyDocument46 paginiCase Study Presented by Group 22 BSN 206: In-Depth View On CholecystectomyAjiMary M. DomingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsDe la EverandGastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsÎncă nu există evaluări

- CholecystectomyDocument6 paginiCholecystectomyTom Bayubs-tucsÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Happens in The Operating RoomDocument137 paginiWhat Happens in The Operating RoomMelchor Felipe Salvosa100% (1)

- Acute Renal FailureDocument17 paginiAcute Renal FailureDina Rasmita100% (1)

- Fistula in AnoDocument3 paginiFistula in Anokhadzx80% (5)

- Common Surgical Procedures TerminologyDocument10 paginiCommon Surgical Procedures TerminologySara Tongcua TacsagonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intestinal ObstructionDocument35 paginiIntestinal Obstructionwht89100% (1)

- CholelithiasisDocument37 paginiCholelithiasisbaby padzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Esophageal ObstructionDocument18 paginiEsophageal ObstructionArun Murali50% (2)

- Appendicitis Case StudyDocument10 paginiAppendicitis Case StudyMarie JoannÎncă nu există evaluări

- AppendectomyDocument5 paginiAppendectomyCris EstoniloÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diverticular DiseaseDocument15 paginiDiverticular DiseaseRogie SaludoÎncă nu există evaluări

- CholelithiasisDocument3 paginiCholelithiasisMIlanSagittarius0% (1)

- Enterocutaneous FistulaDocument52 paginiEnterocutaneous FistulawabalyÎncă nu există evaluări

- GOUT Case StudyDocument3 paginiGOUT Case StudySunshine_Bacla_42750% (1)

- FINAL CHOLE,,,Sa Wakas TpozDocument64 paginiFINAL CHOLE,,,Sa Wakas TpozakatzkiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Laparoscopic CholecystectomyDocument41 paginiLaparoscopic CholecystectomyLim MelaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment and Management of Patients With Biliary DisordersDocument26 paginiAssessment and Management of Patients With Biliary DisordersBav VAansoqnuaetz100% (1)

- EpistaxisDocument22 paginiEpistaxisDood100% (1)

- Final CholelithiasisDocument36 paginiFinal CholelithiasisRalph Pelegrino100% (2)

- Cholelithiasis 0232Document118 paginiCholelithiasis 0232Kz LonerÎncă nu există evaluări

- AppendectomyDocument35 paginiAppendectomyleighjagÎncă nu există evaluări

- RBS and FBSDocument5 paginiRBS and FBSAllenne Rose Labja Vale100% (1)

- Acute AppendicitisDocument63 paginiAcute AppendicitisIsis Elektra100% (1)

- DEFINITION: Abortion Is The Expulsion or Extraction From Its MotherDocument10 paginiDEFINITION: Abortion Is The Expulsion or Extraction From Its MothermOHAN.SÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case Study CholecystitisDocument27 paginiCase Study CholecystitisBandana RajpootÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Surgical ProceduresDocument6 paginiList of Surgical ProceduresMatin Ahmad KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open CholecystectomyDocument15 paginiOpen CholecystectomyjimdioÎncă nu există evaluări

- EpisiotomyDocument18 paginiEpisiotomyAnnapurna DangetiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classification of Instruments and It's RecDocument48 paginiClassification of Instruments and It's RecLeni CarununganÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is TAHbsoDocument2 paginiWhat Is TAHbsomiskidd100% (2)

- Peptic Ulcer Disease FDocument51 paginiPeptic Ulcer Disease FSharmila Laxman Dake100% (2)

- Case Presentation TetanusDocument15 paginiCase Presentation TetanusukhtianitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute and Chronic GastritisDocument17 paginiAcute and Chronic GastritisIndah Nur PratiwiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brain TumorDocument7 paginiBrain TumorPintu Kumar100% (1)

- PancreatitisDocument7 paginiPancreatitisavigenÎncă nu există evaluări

- CellulitisDocument37 paginiCellulitisRobin HaliliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Acute Renal Failure Case Presentation GRP 3Document60 paginiAcute Renal Failure Case Presentation GRP 3varish100% (1)

- Acute Gastroenteritis For PediatricsDocument12 paginiAcute Gastroenteritis For PediatricsJamila B. MohammadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Care Plan of Colorectal PatientDocument16 paginiNursing Care Plan of Colorectal PatientIkenna Okpala100% (2)

- Acute PancreatitisDocument7 paginiAcute PancreatitisVytheeshwaran Vedagiri100% (9)

- A Case Presentation On AppendecitisDocument30 paginiA Case Presentation On AppendecitisrodericpalanasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Exstrophy of BladderDocument34 paginiExstrophy of BladdersudhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intestinal Obstruction 4Document25 paginiIntestinal Obstruction 4Muvenn KannanÎncă nu există evaluări

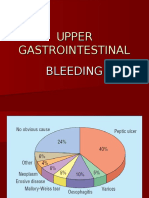

- Upper Gi BleedingDocument35 paginiUpper Gi Bleedingnawriirwan100% (1)

- Acute Cholecystitis: Pableo, Rachel MDocument47 paginiAcute Cholecystitis: Pableo, Rachel MLd Rachel PableoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oesophageal Atresia by GabriellaDocument7 paginiOesophageal Atresia by GabriellaGabrielleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Extrahepatic Biliary Tract Pathology - Cholidolithiasis, Cholidocholithiasis, Cholecystitis and CholangitisDocument60 paginiExtrahepatic Biliary Tract Pathology - Cholidolithiasis, Cholidocholithiasis, Cholecystitis and CholangitisDarien LiewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management of Tuberculosis: A guide for clinicians (eBook edition)De la EverandManagement of Tuberculosis: A guide for clinicians (eBook edition)Încă nu există evaluări

- Nurses' Notes: Patient Cherry Dr. MDocument4 paginiNurses' Notes: Patient Cherry Dr. MNicxx GamingÎncă nu există evaluări

- History TakingDocument5 paginiHistory Takingolwethu.mpepandukuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drug Overdose: Dr. Diah Ari Safitri, SPPDDocument9 paginiDrug Overdose: Dr. Diah Ari Safitri, SPPDmkafabillahÎncă nu există evaluări

- PTSD PaperDocument7 paginiPTSD PaperBeccaShanksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Appendix 7 Infection ContrDocument3 paginiAppendix 7 Infection ContrAninditaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Surgical Technologist Job DescriptionDocument2 paginiSurgical Technologist Job DescriptionMeha FatimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Haploidentical Stem Cell Transplant: Zeina Al-Mansour, MDDocument22 paginiHaploidentical Stem Cell Transplant: Zeina Al-Mansour, MDAymen OmerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Efektifitas Pelatihan High Alert Medication Terhadap Pengetahuan Dan Sikap Petugas Di RS KIA PKU Muhammadiyah KotagedeDocument4 paginiEfektifitas Pelatihan High Alert Medication Terhadap Pengetahuan Dan Sikap Petugas Di RS KIA PKU Muhammadiyah KotagedeNindy C AbriantyÎncă nu există evaluări

- WHO Guidelines On Drawing BloodDocument125 paginiWHO Guidelines On Drawing BloodAnonymous brvvLxoIlu100% (1)

- Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument12 paginiChronic Kidney DiseaseRoseben SomidoÎncă nu există evaluări

- FE ImbalanceDocument6 paginiFE ImbalanceDonna CortezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secondary Endolymphatic HydropsDocument6 paginiSecondary Endolymphatic HydropsjwilnerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Narrative Report-Mam Monsanto2Document3 paginiNarrative Report-Mam Monsanto2Annie Lucrecia Mallari AguinaldoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurnal Code Blue PDFDocument4 paginiJurnal Code Blue PDFAfi Adi KiranaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Triage PrinciplesDocument2 paginiTriage PrinciplesMabesÎncă nu există evaluări

- DKA, HONKS, HHS (Theory)Document26 paginiDKA, HONKS, HHS (Theory)EleanorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stroke (Brain Attack)Document16 paginiStroke (Brain Attack)Nhayr Aidol100% (1)

- A Healthier Tomorrow: Norfolk General Hospital's New Strategic PlanDocument19 paginiA Healthier Tomorrow: Norfolk General Hospital's New Strategic Planggrrk7Încă nu există evaluări

- Nursing DiagnosisDocument3 paginiNursing DiagnosislesternÎncă nu există evaluări

- DjdlkjsaljdljlDocument18 paginiDjdlkjsaljdljlEricÎncă nu există evaluări

- Physiological Rationale and Current Evidence For Therapeutic Positioning of Critically Ill Patients PDFDocument15 paginiPhysiological Rationale and Current Evidence For Therapeutic Positioning of Critically Ill Patients PDFnurulanisa0703Încă nu există evaluări

- RamiprilDocument3 paginiRamiprilapi-3797941Încă nu există evaluări

- Middle Third Fracture MCQDocument6 paginiMiddle Third Fracture MCQhaneefmdf83% (6)

- Model Paper ADocument7 paginiModel Paper AAndrewwwCheahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentasi Pit Perbani 2000Document16 paginiPresentasi Pit Perbani 2000Meta ParamitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alzehimer GuiaDocument9 paginiAlzehimer GuiaAlejandro PiscitelliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Implant SurgeryDocument7 paginiBasic Implant SurgeryDr.Ankur Gupta100% (1)

- Cifras de Refer en CIA de Laboratorio - Harriet LaneDocument18 paginiCifras de Refer en CIA de Laboratorio - Harriet LaneLicea Bco JoseÎncă nu există evaluări

- tmpB433 TMPDocument9 paginitmpB433 TMPFrontiersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comp Predictor Quizlet Study GuideDocument20 paginiComp Predictor Quizlet Study GuideJennifer Vicioso100% (9)