Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Index 2

Încărcat de

stark2006Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Index 2

Încărcat de

stark2006Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The Practical Lawyer

Freedom of press in India : Constitutional Perspectives

Freedom of press in India : Constitutional Perspectives by Dr. Mahendra Tiwari* Cite as: (2006) PL December 7 The Freedom of press includes more than merely serving as a “neutral conduit of information between the people and their elected leader or as a neutral form of debate”. In India before Independence, there was no constitutional or statutory guarantee of freedom of an individual or media/press. At most, some common law freedom could be claimed by the press, as observed by the Privy Council in Channing Arnold v. King Emperor1: “The freedom of the journalist is an ordinary part of the freedom of the subject and to whatever length, the subject in general may go, so also may the journalist, but apart from statute law his privilege is no other and no higher. The range of his assertions, his criticisms or his comments is as wide as, and no wider than that of any other subject.” With object and views, the Preamble of the Indian Constitution ensures to all citizens inter alia, liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship. The constitutional significance of the freedom of speech consists in the Preamble of Constitution and is transformed as fundamental and human right in Article 19(1)(a) as “freedom of speech and expression”. The present study is intended to present the provisions of the Indian Constitution and other national instruments which recognise the freedom of press as an integral part of the freedom of speech and expression, the basic fundamental rights of human being. It is also to be examined how far freedom of press has constitutional significance in achieving the free, fair and real democracy. The study also covers the view taken by the Hon’ble Supreme Court on the subject. The main object of providing guaranteed freedom of press is for creating a fourth institution beyond the control of State authorities, as an additional check on the three official branches—the executive, the legislature and the judiciary.2 It is the primary function of the press to provide comprehensive and objective information on all aspects of the country’s social, economic and political life. For achieving the main objects, freedom of the press has been included as part of freedom of speech and expression which is a universally recognised right adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations Organization on 10th December, 1948. The heart of the declaration contained in Article 19 says as follows: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression, this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” The same view of freedom of holding opinions without interference has been taken by the Supreme Court in Union of India v. Assn. for Democratic Reforms3 in which the Court has observed as follows: (SCC p. 317, para 38) “[O]ne-sided information, disinformation, misinformation and non information, all equally create an uninformed citizenry which makes democracy a farce. … Freedom of speech and expression includes right to impart and receive information which includes freedom to hold opinions.” In India, freedom of press is implied from the freedom of speech and expression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India. Article 19(1)(a) says that all citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression. But this right is subject to reasonable restrictions imposed on the expression of this right for certain purposes under Article 19(2). Article 19(1)(a) corresponds to the First Amendment of the United States Constitution which says, “congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech or of the press”4. The provisions in the US Constitution has two notable features i.e.:

- freedom of press is specifically mentioned therein, - no restrictions are mentioned on the freedom of speech. But the Supreme Court of India has held that there is no specific provision ensuring freedom of the press separately. The freedom of the press is regarded as a “species of which freedom of expression is a genus”. Therefore, press cannot be subjected to any special restrictions which could not be imposed on any private citizen,5 and cannot claim any privilege (unless conferred specifically by law), as such, as distinct from those of any other citizen. Freedom of the press has three essential elements. They are:

- freedom of access to all sources of information either of one’s own views or borrowed from someone else or printed under the direction of the person,6 - freedom of publication, and - freedom of circulation.7 Freedom of speech is the bulwark of democratic Government. In a democracy, freedom of

http://www.supremecourtcases.com Eastern Book Company Generated: Tuesday, February 28, 2012

The Practical Lawyer

speech and expression opens up channels of free discussion of issues. It implies that there should be a close link between the Government and the people. Freedom of speech plays a crucial role in the formation of public opinion on social, political and economic matters. Similarly, the persons in power should be able to keep the people informed about their policies and projects, therefore, it can be said that freedom of speech is the mother of all other liberties.8 Keeping this view in mind Venkataramiah, J. of the Supreme Court of India in Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) (P) Ltd. v. Union of India9 has stated: “In today’s free world freedom of press is the heart of social and political intercourse. The press has now assumed the role of the public educator making formal and non-formal education possible in a large scale particularly in the developing world, where television and other kinds of modern communication are not still available for all sections of society. The purpose of the press is to advance the public interest by publishing facts and opinions without which a democratic electorate [Government] cannot make responsible judgments. Newspapers being purveyors of news and views having a bearing on public administration very often carry material which would not be palatable to Governments and other authorities.” The above statement of the Supreme Court illustrates that the freedom of press is essential for the proper functioning of the democratic process. Democracy means Government of the people, by the people and for the people; it is obvious that every citizen must be entitled to participate in the democratic process and in order to enable him to intelligently exercise his right of making a choice, free and general discussion of public matters is absolutely essential.10 This explains the constitutional viewpoint of the freedom of press in India. In Printers (Mysore) Ltd. v. CTO11 the Supreme Court has reiterated that though freedom of the press is not expressly guaranteed as a fundamental right, it is implicit in the freedom of speech and expression. Freedom of the press has always been a cherished right in all democratic countries and the press has rightly been described as the fourth chamber of democracy. The fundamental principle which was involved in freedom of press is the “people’s right to know”. It therefore received a generous support from all those who believe in the free flow of the information and participation of the people in the administration; it is the primary duty of all national courts to uphold this freedom and invalidate all laws or administrative actions which interfere with this freedom, are contrary to the constitutional mandate.12 In R. Rajagopal v. State of T.N.13 the Supreme Court of India has held that freedom of the press extends to engaging in uninhabited debate about the involvement of public figures in public issues and events. But, as regards their private life, a proper balancing of freedom of the press as well as the right of privacy and maintained defamation has to be performed in terms of the democratic way of life laid down in the Constitution. Therefore, in view of the observations made by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in various judgments and the views expressed by various jurists, it is crystal clear that the freedom of the press flows from the freedom of expression which is guaranteed to “all citizens” by Article 19(1)(a). Press stands on no higher footing than any other citizen and cannot claim any privilege (unless conferred specifically by law), as such, as distinct from those of any other citizen. The press cannot be subjected to any special restrictions which could not be imposed on any citizen of the country. Freedom of press — areas of reasonable restrictions Lord Denning in his book Road to Justice observed that press is the watchdog to see that every trial is conducted fairly, openly and above board, but the watchdog may sometimes break loose and has to be punished for misbehaviour. The dangers of the uncanalised discretion given to Lok Adalats have been recognised by some States and pursuant to Section 28 of the Legal Services Authorities Act, Regulations have been framed in relation to the conduct of Lok Adalats. The Kerala Regulations, 1998, framed by the Kerala Legal Services Authority (KELSA), provide a model of good practice. Regulation 28 makes it mandatory for notice to be issued to the parties in a dispute in order to enable them to prepare their case. This embodies the right to a fair hearing. Regulation 31 explicitly lays down that the Bench is to restrain itself to a conciliatory role and make efforts to bring about a settlement “without bringing about any kind of coercion, threat or undue influence, allurement or misrepresentation”. Under Regulation 33, the Bench is required to obtain the signatures of the parties to the dispute, in addition to the signatures of the Members of the Bench. This Regulation ensures that the parties are given adequate notice and are present during the proceedings. It is necessary to maintain and preserve freedom of speech and expression in a democracy, so also it is necessary to place some restrictions on this freedom for the maintenance of social order, because no freedom can be absolute or completely unrestricted. Accordingly, under Article 19(2) of the Constitution of India, the State may make a law imposing “reasonable restrictions” on the exercise of the right to freedom of speech and expression “in the interest of” the public on the following grounds:

http://www.supremecourtcases.com

Eastern Book Company

Generated: Tuesday, February 28, 2012

The Practical Lawyer

- security of the State, - friendly relations with foreign States, - public order, - decency and morality, - contempt of court, - defamation, - incitement to an offence, and - sovereignty and integrity of India. Grounds contained in Article 19(2) show that they are all concerned with the national interest or in the interest of the society. The first set of grounds i.e. the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States and public order are all grounds referable to national interest, whereas, the second set of grounds i.e. decency, morality, contempt of court, defamation and incitement to an offence are all concerned with the interest of the society. As we concern with the restrictions imposed upon the media, it is clear from the above that a court evaluating the reasonableness of a restriction imposed on a fundamental right guaranteed by Article 19 enjoys a lot of discretion in the matter. It is the constitutional obligation of all courts to ensure that the restrictions imposed by a law on the media are reasonable and relate to the purposes specified in Article 19(2). In Papnasam Labour Union v. Madura Coats Ltd.14 the Hon’ble Supreme Court has laid down some principles and guidelines to be kept in view while considering the constitutionality of a statutory provision imposing restriction on fundamental rights guaranteed by Articles 19(1)(a) to (g) when challenged on the grounds of unreasonableness of the restriction imposed by it. In Arundhati Roy, In re15 the Hon’ble Supreme Court has considered the view taken by Frankfurter, J. in Pennekamp v. Florida16 in which Judge of the United States observed: (US p. 366) “If men, including judges and journalists, were angels, there would be no problem of contempt of court. Angelic judges would be undisturbed by extraneous influences and angelic journalists would not seek to influence them. The power to punish for contempt, as a means of safeguarding judges in deciding on behalf of the community as impartially as is given to the lot of men to decide, is not a privilege accorded to judges. The power to punish for contempt of court is a safeguard not for judges as persons but for the function which they exercise.” In Rajendra Sail v. M.P. High Court Bar Assn.17 the editor, printer and publisher and a reporter of a newspaper, along with the petitioner who was a labour union activist, were summarily punished and sent to suffer a six months’ imprisonment by the High Court. Their fault was that on the basis of a report filed by a trainee correspondent, they published disparaging remarks against the judges of a High Court made by a union activist at a rally of workers. The remarks were to the effect that the decision given by the High Court was “rubbish” and “fit to be thrown into a dustbin”. In appeal the Supreme Court upheld the contempt against them, but modified and reduced the sentence. In D.C. Saxena (Dr.) v. Chief Justice of India18 the Hon’ble Supreme Court has held that no one else has the power to accuse a judge of his misbehaviour, partiality or incapacity. The purpose of such a protection is to ensure independence of judiciary so that the judges could decide cases without fear or favour as the courts are created constitutionally for the dispensation of justice. By these above observations and the judgment we can say that restrictions imposed by Article 19(2) upon the freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by Article 19(1)(a) including the freedom of press serve a two-fold purpose viz. on the one hand, they specify that this freedom is not absolute but are subject to regulation and on the other hand, they put a limitation on the power of a legislature to restrict this freedom of press/media. But the legislature cannot restrict this freedom beyond the requirements of Article 19(2) and each of the restrictions must be reasonable and can be imposed only by or under the authority of a law, not by executive action alone. Conclusion and suggestions In democracy, the Government cannot function unless the people are well informed and free to participate in public issues by having the widest choice of alternative solutions of the problems that arise. Articles and news are published in the press from time to time to expose the weaknesses of the governments. The daily newspaper and the daily news on electronic media are practically the only material which most people read and watch. The people can, therefore, be given the full scope for thought and discussion on public matter, if only the newspapers and electronic media are freely allowed to represent different points of views, including those of the opposition, without any control from the Government. The following suggestions are offered in this connection:

- Freedom of press may be inserted as a specific fundamental right under Article 19 of the Constitution of India. - Parameters of freedom of press should be clearly earmarked. - Information must be available at an affordable cost within specified, definite and reasonable time-limits. - Free press should not violate right to privacy of an individual.

http://www.supremecourtcases.com Eastern Book Company Generated: Tuesday, February 28, 2012

The Practical Lawyer

- Free press must be law enforcing and preventive of crime. - Rule of law must be followed by the free press. - Influence through free press upon the judiciary should not be exercised.* LLM PhD, Vice Principal, Rajputana Vidhi Mahavidyalaya, JPR.

- AIR 1914 PC 116, 117 - New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 US 255 (1964). New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 US 713 (1971) (known as the Pentagon Papers case) - (2002) 5 SCC 294 - See M.P. Jain, Indian Constitutional Law, (5th Edn.). - Sakal Papers (P) Ltd. v. Union of India, AIR 1962 SC 305 - M.S.M. Sharma v. Sri Krishna Sinha, AIR 1959 SC 395, 402 - Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras, 1950 SCR 594, 607 - Report of the Second Press Commission, Vol. I, 34-35 - (1985) 1 SCC 641 at p. 664, para 32. - Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, (1978) 1 SCC 248 - (1994) 2 SCC 434 - Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) (P) Ltd. v. Union of India, (1985) 1 SCC 641 - (1994) 6 SCC 632 - (1995) 1 SCC 501 - (2002) 3 SCC 343 - 328 US 331 : 90 L Ed 1295 (1946) - (2005) 6 SCC 109 per Y.K. Sabharwal, J. (for himself and Tarun Chatterjee, J.) - (1996) 5 SCC 216

http://www.supremecourtcases.com

Eastern Book Company

Generated: Tuesday, February 28, 2012

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (895)

- Prot Testing SchedulesDocument3 paginiProt Testing Schedulesstark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- SyrotechDocument6 paginiSyrotechstark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- Prot Testing SchedulesDocument3 paginiProt Testing Schedulesstark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (588)

- SCI Response To Pre Bid Queries Raised by Bidders On 06 July 2012Document4 paginiSCI Response To Pre Bid Queries Raised by Bidders On 06 July 2012stark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- LLRO Version G Marked 29-06-2012Document84 paginiLLRO Version G Marked 29-06-2012stark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- GTP Scope Tech Specs115Document5 paginiGTP Scope Tech Specs115stark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- Proposal For Dedicated Internet BandwidthDocument3 paginiProposal For Dedicated Internet Bandwidthjsri100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (400)

- Slyt480 PDFDocument6 paginiSlyt480 PDFstark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Premie 300 User Manual (Secure), BGX501-747-R04Document41 paginiPremie 300 User Manual (Secure), BGX501-747-R04stark200671% (24)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- Cloud Hosting SlaDocument7 paginiCloud Hosting Slastark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- AQ - HTML: This Document Does Not Represent The Agreed Views of The IEEE 802.16 Working Group or Any of Its Subgroups. ItDocument5 paginiAQ - HTML: This Document Does Not Represent The Agreed Views of The IEEE 802.16 Working Group or Any of Its Subgroups. Itstark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- ControllerProtocolV2 3Document17 paginiControllerProtocolV2 3stark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Deltapage Server PriceDocument1 paginăDeltapage Server Pricestark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- Sertel T PAN 300 CatalogueDocument2 paginiSertel T PAN 300 Cataloguestark200650% (2)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (266)

- Documents - MX Smo-DataDocument2.291 paginiDocuments - MX Smo-Datastark20060% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (345)

- Federal Court Re-Affirms E-Discovery Requests Must Be Specific About Format and MetadataDocument3 paginiFederal Court Re-Affirms E-Discovery Requests Must Be Specific About Format and Metadatastark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (74)

- Processing Error: Use Another MethodDocument1 paginăProcessing Error: Use Another Methodstark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2259)

- RSM Asm Telephone ListDocument2 paginiRSM Asm Telephone Liststark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Chilli Paneer ReceipeDocument8 paginiChilli Paneer Receipestark2006Încă nu există evaluări

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Intersectionality 101 PDFDocument17 paginiIntersectionality 101 PDFAlex BurkeÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- Antonio Negri - TerrorismDocument5 paginiAntonio Negri - TerrorismJoanManuelCabezasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consti Full TextDocument196 paginiConsti Full Textclaire beltranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Private Military CompaniesDocument23 paginiPrivate Military CompaniesAaron BundaÎncă nu există evaluări

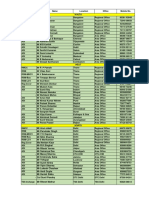

- S.N. Sapid# Location Next Assessment Date. Last Assessed On Approval Scope Saudi Aramco Approved StockistDocument1 paginăS.N. Sapid# Location Next Assessment Date. Last Assessed On Approval Scope Saudi Aramco Approved StockistShalom LivingstonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Human Rights, Refugee Law, and International Humanitarian Law - 2 TOPIC: - "Protection of Human Rights in India"Document6 paginiHuman Rights, Refugee Law, and International Humanitarian Law - 2 TOPIC: - "Protection of Human Rights in India"Sanyam MishraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rearranging Ireland's Public Dance Halls Act of 1935Document12 paginiRearranging Ireland's Public Dance Halls Act of 1935Elaine ClaytonÎncă nu există evaluări

- LP 1f-g30 Assess The Effects of The Colonial ExperienceDocument3 paginiLP 1f-g30 Assess The Effects of The Colonial ExperienceSharon Abang TropicoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Colonel Alan Brooke Pemberton & Diversified Corporate Services Limited - MI6 Front Companies in GermanyDocument26 paginiColonel Alan Brooke Pemberton & Diversified Corporate Services Limited - MI6 Front Companies in GermanyAlan Pemberton - DCSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Washington D.C. Afro-American Newspaper, January 23, 2010Document24 paginiWashington D.C. Afro-American Newspaper, January 23, 2010The AFRO-American NewspapersÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (121)

- Sababiyyah - CausalityDocument24 paginiSababiyyah - CausalityNoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Faiz Ahmad-2003Document2 paginiFaiz Ahmad-2003faizÎncă nu există evaluări

- KFHG Gender Pay Gap Whitepaper PDFDocument28 paginiKFHG Gender Pay Gap Whitepaper PDFWinner#1Încă nu există evaluări

- David Altman - Direct Democracy in Comparative Perspective. Origins, Performance, and Reform-Cambridge University Press (2019) PDFDocument271 paginiDavid Altman - Direct Democracy in Comparative Perspective. Origins, Performance, and Reform-Cambridge University Press (2019) PDFfelixjacomeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thus Speaks Qadosh ErectusDocument349 paginiThus Speaks Qadosh Erectuscaseyzan90% (10)

- Bodenhausen & Peery (2009) - Social Categorization and StereotypeingDocument22 paginiBodenhausen & Peery (2009) - Social Categorization and StereotypeingartaudbasilioÎncă nu există evaluări

- 794-Article Text-3327-2-10-20200630Document16 pagini794-Article Text-3327-2-10-20200630Koreo DrafÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technological Revolution and Its Moral and Political ConsequencesDocument6 paginiTechnological Revolution and Its Moral and Political ConsequencesstirnerzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Claremont Courier 5.10.13Document36 paginiClaremont Courier 5.10.13Claremont CourierÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1984Document119 pagini1984Ravneet Singh100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Civil Military RelationsDocument13 paginiCivil Military RelationsKhadijaSaleemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lee Ward-The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America (2004)Document469 paginiLee Ward-The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America (2004)VagabundeoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mg350 All PagesDocument24 paginiMg350 All PagessyedsrahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Stages of Public PolicyDocument1 paginăStages of Public PolicySuniel ChhetriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Times Leader 05-16-2012Document42 paginiTimes Leader 05-16-2012The Times LeaderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transport Infrastructure and The Road To Statehood in SomalilandDocument10 paginiTransport Infrastructure and The Road To Statehood in SomalilandOmar AwaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Last Grade 3607-11-2012-mpmDocument24 paginiLast Grade 3607-11-2012-mpmSudheendranadhan KVÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Study of Cities: Historical and Structural Approaches: Pieter SaeyDocument30 paginiThe Study of Cities: Historical and Structural Approaches: Pieter Saeyirving_washington1Încă nu există evaluări

- Communists Take Power in China PDFDocument2 paginiCommunists Take Power in China PDFDianeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Toxic Charity: How Churches and Charities Hurt Those They Help (And How To Reverse IT)Document14 paginiToxic Charity: How Churches and Charities Hurt Those They Help (And How To Reverse IT)CCUSA_PSMÎncă nu există evaluări