Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Journal of Cleaner Production: Muireann Mcmahon, Tracy Bhamra

Încărcat de

Nishant GuptaDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Journal of Cleaner Production: Muireann Mcmahon, Tracy Bhamra

Încărcat de

Nishant GuptaDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Journal of Cleaner Production

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro

Design Beyond Borders: international collaborative projects as a mechanism to integrate social sustainability into student design practice

Muireann McMahon a, *, Tracy Bhamra b

a b

Dept. of Design & Manufacturing Technology, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland Loughborough Design School, Loughborough, UK

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history: Received 27 January 2011 Received in revised form 14 October 2011 Accepted 15 October 2011 Available online 25 October 2011 Keywords: Social sustainability Collaboration Design education Product Design Action research

a b s t r a c t

Social sustainability in design, like the notion of social impacts in Sustainable Development, is a complex, contradictory and challenging area. Transforming the rhetoric surrounding sustainability into action is where designers often struggle. In order to do this effectively, this paper argues that designers need to be introduced to a set of skills and capacities that go beyond the traditional design competencies and implementing these skills will require a shift in how designers are taught as students and subsequently practice as professionals. Through the exploration of contemporary design practices, social sustainability and educational theory this research pinpoints these skills and capacities. Using a participatory Action Research methodology it is suggested that international collaborative projects at undergraduate level can play an important role in introducing these skills into design education. The paper describes two projects (fullling two phases of the action research process) involving collaborations between groups of undergraduate design students from different geographical locations. A brief description of the projects logistics is followed by an analysis of the outcomes and experiences of participants, looking specically at what worked and what did not and why mistakes and successes in collaborative work can inform in equal measure. The learning from these projects will highlight how future projects can be structured and delivered and how the softer skills acquired during the projects can bring about a change in designers behaviours. 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction Today there is an impetus on professional designers to practice in a responsible and sustainable manner, with equal emphasis on society, economy and the environment (Fletcher and Dewberry, 2002). This is an enormous challenge as the skills needed to develop these types of holistic solutions can be extremely complex. Yet education often fails to equip design students with the necessary skills that allow them to practice responsibly as professionals (ibid). This paper provides the rst output of a larger longitudinal project. The key premise of the overall study is to investigate how social sustainability can be integrated into design1 education to encourage more responsible professional practices. The work focuses on international collaborative projects as a mechanism to foster the necessary skills and encourage students to look more broadly and critically at their own work and that of others. Fig. 1 illustrates the overall project map from the key aims at the centre

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 353 61 213580. E-mail address: Muireann.mcmahon@ul.ie (M. McMahon). 1 Design for this paper refers to Product or Industrial Design. 0959-6526/$ e see front matter 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.10.022

of the diagram to the research methodology (left) for testing and the skills and capacities on the right. The paper begins by grounding these projects in current theory surrounding contemporary design, social sustainability and educational practices. Subsequently, a brief outline is given of two projects conducted between students from Universities in New Zealand, Ireland and Chile (who unfortunately were forced to withdraw in the initial stages of the 2nd project). The paper explains the practical logistics of planning and implementing such projects acknowledging the difculties and realities involved. It documents the conversations, conicts and compromises that occur and the contingencies (unforeseen or uncontrollable actions) that can thwart or enhance the experience. The discussion describes how the ndings from the rst phase of research informed the design and implementation of the second project. Finally the conclusion offers a reection on the experiences of both students and tutors and indicates the future phases of Action Research that will complete the study. These collaborative projects build on the premise that the broader the diversity of information, practices and cultures design students are exposed to the more open their perspectives will be

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

87

Fig. 1. Project overview.

and the more adept they will become at participating in and facilitating the creation of more innovative sustainable solutions. The results of these projects are explored to assess their impact in beginning to bring about increases in social capital, social cohesion and collaboration across geographical and educational boundaries. 2. Background The paradigm of design is changing; with the focus moving away from material led objects to more user-led experiences (Moritz, 2005). The notion of a designers role as that of merely giving shape to physical objects is no longer valid (Nelson and Stolterman, 2003). Design has evolved to become the link between human and social needs and industrial practices. This is achieved by designing tangible and intangible objects that give meaning, provide cultural contexts and also the opportunities for individual expression (Hara, 2009). Design now acts as cultural stimulus, a change agent and a tool for social engagement. The development of innovative design solutions may be greatly enhanced through a process of collaboration, collective knowledge generation and sharing, multi-disciplinarity, holistic perspectives and understanding of diverse cultural backgrounds (Designophy, 2001). Encouraging and facilitating collaboration between students in an educational environment can be particularly challenging as individuals can struggle to move past what they know and have learnt in their own cultural and professional settings (Cumming and Akar, 2005). Educating for sustainable development focuses students on gaining exposure to diversities of practice so as to develop critical thinking and analysis skills. Fortunately, as Bhamra and Dewberry note, best practice design education maps relatively easily onto the adoption of sustainable development teaching methodologies as both encourage pragmatism and participation (2007). To engage fully with sustainability, designers today must learn to engage in cross-disciplinary and cross cultural dialogue. If students are to be responsible, innovative and pragmatic designers, they must develop the ability to think critically; tie together disparate strands of information; communicate effectively (talking and listening); apply systems thinking; co-operate in co-design

projects whilst also imagining and realising new ideas (Chiu, 2002; Lozano, 2007; Manzini, 2009b). Both knowledge sharing and collaborative practice serve to open these communication channels and create a community of informed and informative professionals (Cumming and Akar, 2005). This deeper approach to design (and consequently education) poses a huge challenge as it requires a change in both behaviour and attitudes (Thackara, 2006). What will be required is a new way of learning that is creative and involves a deep awareness of alternative worldviews and ways of doing things (Sterling, 2001) and prepares students for the realities they will face as professionals. Collaborative project work not only serves to broaden students perspectives, but also facilitates them to become critical thinkers who question, analyse, reect and consequently form their own worldview (Chiu, 2002). Resultantly they may critically question their own education and behaviours, as well as learning to comment and critique on other design work by engaging in dialogue with a wide variety of designers from diverse cultural backgrounds as Lozano Garca et al. (2006) suggest within and across other disciplines. The curriculum therefore must stimulate the students into exploring alternative approaches to design, in a real and engaged way. From the tutors perspective this will help to broaden and develop the experience for their students and will emphasise the importance of making project work relevant within the global context. 2.1. Social sustainability in design As justication for the collaborative projects and to provide a background context it was necessary to rst identify what social sustainability is in relation to design and also to collate a list of relevant skills and capacities designers needed to develop in order to practice responsibly. It is generally accepted that sustainability incorporates three central tenets (social, economic and environmental) in equal measure. Addressing these in equal measure is where problems have arisen as every discipline and culture come from very different perspectives and therefore have very different needs (Cassimir and Dutilh, 2003; Moore, 2011). Each discipline interprets the desired

88

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

outcomes from their own perspective and to date this focus in design has been on environmental and economic factors. End of pipe solutions, energy and resource use, green materials and processes and more recently social innovations, systems design and design for behaviour change have dominated the sustainable and eco-design agendas (Chapman, 2005; Sherwin, 2004; Dewberry, 1996; Krull, 2010; Manzini, 2009a). Social sustainability in design, as in other areas, has been somewhat neglected, as it is difcult to dene and even more difcult to implement (Steiner and Posch, 2006, Cassimir and Dutilh, 2003). This ambiguity stems from the fact that it involves issues as diverse (and unquantiable) as ethics, values, active citizenship, harmonious behaviour, participation and co-operation, preserving social and cultural diversity, meeting basic needs, well-being and happiness, holistic perspectives and personal as well as professional responsibility (Lilley, 2007; McKenzie, 2004). Social sustainability in design, therefore calls for a deep understanding of human behaviour, fullling human needs and wants whilst being cognisant of (amongst other things) environmental limits, product responsibility, resource use and carrying capacities. As well as paying due attention to history; traditions; engaging in dialogue; having equity in expressing ideas; compromise; selffullment and altruism in design practice are fundamentals in working towards social sustainability. These have been categorised as social capital, social engagement, social cohesion and social exclusion (Bramley et al., 2006; Findeli, 2008). Sustainable design has progressed from the green design agenda into a far more considered and holistic approach that should be integrated into the education of designers (Spangenberg et al., 2010); if the philosophies are embedded early then responsible practice becomes normative (Bremer and Lpez-Franco, 2006; Lozano, 2006). The debate around social design and the meaning of social sustainability within design practice has been interpreted in numerous different ways. It is often thought of as designing for marginal sectors of society in order to even the disparities in living standards and qualities of life (design for society) (Whiteley, 1993). Similarly incorporating considerations of culture and cultural meaning in products can be classied as social design (Walker, 2006), as can design processes that employ psychology and motivational strategies to lighten human impact (Design for behaviour change) (Manzini, 2007; Mendoza, 2010). Practitioners at the DESIS network, Designmatters, Project H and The Young Foundation would equate the term social sustainability with social innovation and entrepreneurship projects that are based on employing designthinking to bring about positive social changes (Mendoza, 2010; Manzini, 2010; Murray et al., 2010; Core77, 2010). While the approach in the interpretation and understanding may vary, social sustainability in design is about harnessing human and cultural capital to bring about change and regain social cohesion. While there is no one size ts all denition for social sustainability, as social parameters differ from place to place, person to person and context to context, there is a need to overcome the complexity that surrounds it by bringing it into design practices in a real and engaging way (Steiner and Posch, 2006). The critical, creative and systemic thinking approach advocated through social sustainability offers great potential for making designers aware of the impact their products have on both local and global societies. As this awareness grows, designers can feel enabled to change their practice and as a result impact positively on consumption and behavioural patterns of end users. 2.2. Design education for sustainability Unfortunately the problems linked with sustainability and in particular social sustainability are by their very nature extremely

complex and wicked (Design Council, 2006; Steiner and Posch, 2006). As a result students nd it difcult to marry the complicated, contradictory and all too often confusing concepts that underpin it (Segalas et al., 2010). Interestingly though introducing design for sustainability into design education has proven to stimulate creativity and originality (Spangenberg et al., 2010). If we accept that the challenges are great as are the opportunities then the approach for bringing about change demands a rethink of both design practice and education. Education and Sustainability are inextricably linked as education is seen as the key to effectively implement change (McKeown, 2002). There is no denying that education is pivotal in realising the vision and translating the rhetoric into real action (UN, 2005, UNESCO, 2004). It is widely recognized that design practices must move from a parochial to a global approach where openness, transparency and collaboration (co-design & co-generation) allow for a greater freedom of ideas and solutions (Jegou and Manzini, 2008; Moritz, 2005; Burns et al., 2006). Collaboration and co-operation encourage social learning, allow designers to hear other voices, build on both collective and individual knowledge and develop softer design skills like compromise, dialogue, reection and empathy (Chiu, 2002; Steiner and Posch, 2006, Fadeeva, 2004). Creativity too is known to be heightened when culturally diverse teams work together (McDonough et al., 2001). Therefore an imperative exists to not only change what is taught to design students (curriculum content) but also how the core skills are taught (teaching methods) (Bhamra and Dewberry, 2007). Designers need to develop a holistic perspective backed by the ability to think critically and creatively, to self-direct and reect on their design outputs and the resultant impacts on society. The skills of effective communication and collaboration underpin these abilities (Lozano, 2007). Reection is an essential part of educational practice, as it allows the students to question their own assumptions and those of others in order to build a broader knowledge base for their professional practice (Loughran, 2002). As with any effective learning strategy the process should be stressed as highly as the outcomes. Many authors recommend developing in students a generic range of skills and capacities that facilitate them in understanding, managing and questioning knowledge and then implementing change and effecting action (McKeown, 2002; Sterling, 2001, Gonzlez-Gaudiano, 2005; Steiner and Posch, 2006, Chiu, 2002; Manzini, 2009b). Stage 1 of the research involved exploring and gaining an understanding of what these skills are. From a combination of brainstorming, reviewing literature2, peer discussions, observations and practical experience a list of skills, capacities and ideas have been identied as those needed for socially sustainable designing (see Fig. 2 for the complete list of skills, ideas and capacities).

3. Methods 3.1. Aim The overall aim of the larger study is to investigate the use of international collaborative design projects as a mechanism to equip students with the skills and capacities necessary to integrate social sustainability into their daily design practice. The two projects are

2 The literature review covered reading in the areas of Sustainable Development; sustainable design; social design practices; Education for Sustainable Development; design education; contemporary design practices; collaboration; problem solving and creativity.

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

89

Fig. 2. Skills and capacities for social sustainability in design.

described briey in Section 4 and the outcomes discussed in Section 5. 3.2. Research method The research is conducted using Participatory Action Research as the overarching strategy. Fig. 3 provides an overview of this process and also explains the characteristics that are key to this project. Action research (AR) is appropriate as it is a method used when an issue has been identied with existing practice and requires

intervention to solve it (Baskerville and Wood-Harper, 1996); in this case the issue is the difculty of integrating complex ideas (surrounding social sustainability) into designers daily practice. The pragmatic nature of AR allows for the design students to become active participants in their own education. It also allows for the author to adopt dual roles: as the researcher and as the educator for delivering the projects to the students thus linking theory to practice in a real way (Baskerville and Wood-Harper, 1996, McDowell et al., 2008; McNiff and Whitehead, 2006; Baskerville and Wood-Harper, 1996). There are obvious parallels between planning and structuring an action research project and the design process. The two processes are rmly based on learning by doing and are highly exible in nature. This means both are hinged on the unpredictability of human nature and multivariate real-world environments (Baskerville and Wood-Harper, 1996). The contingencies of working with people include motivations, engagement, behaviour, personal and professional drivers, experience, societal inuences and the uncontrollability of behaviours. Dealing with the opportunities and constraints that these contingencies brought to the projects is a fundamental aspect of the Action Research process (Barbour, 2008). Through a comprehensive process of iteration, continuous improvement these projects will be developed and honed in order to achieve the most appropriate, desirable and innovative solution (development and implementation) (Lawson, 2006). Action research (like design) advocates a learning-by-doing process where mistakes inform the project development just as much as the successes (Baskerville and Wood-Harper, 1996). The research approach therefore is driven by creativity; practical learning; user understanding; iterative development; innovative thinking; appropriate decision making and effective communication. Following the initial problem framing and literature reviewing stages of the AR process the next stage was to design and implement a number of projects to allow the students to develop these skills by opening them to a diversity of knowledge and perspectives. Bringing student groups located in different continents together face-to-face is not feasible or environmentally responsible! The softer skills, being more abstract and complex became the implicit focus in the projects rather than the more explicit practical design skills such as idea generation, visual communication and design development etc. Instead the processes the students undertook to complete the work required them to use softer skills in order to collaborate and communicate effectively and to generate necessary, valid and responsible design solutions.

Fig. 3. Action research project map.

90

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

3.3. Data collection and analysis The data collection methods involved a mix of qualitative information gathering tools. Two phases of information occurred during each project: the rst was during the project and the second after the project was completed. Diaries, participant observations, videos and in-class reection sessions comprised the rst stage of information gathering. Stories of participant experiences were collated through this rst stage. The second stage of data was gathered after each project ended. Semi-structured interviews (with students), analysis of the project design outputs, post-project questionnaires and anecdotal conversations (between design tutors and students) identied how the various skills and capacities developed and were implemented. This mix of methods allowed for the researcher to triangulate the data and develop thick descriptions of the situations (Barbour, 2008). Peer auditing between the tutors on the projects (of which the researcher was one) and other design tutors who were not directly involved in the projects ensured the instance of reexivity was minimised. Following the collation of the research data it was analysed and organised according to preliminary codes e using the constant comparative method (Jupp, 2006). These codes were then further subdivided and this coding system was applied across the interviews and diaries. 4. The projects Table 1 4.1. Cultural leanings: phase 1 action research Phase one of the Action Research strategy comprised a collaborative project undertaken between the year 2 undergraduate Product Design students in Unitec, Auckland, New Zealand and the University of Limerick, Ireland (from February to April 2008). The idea for the project originated from a staff exchange between two design tutors from the Institutes. The key aim was to explore the concept of connectivity and interactivity between two culturally different student groups divided by almost 18,000 kms and 12 international time-zones. It was not a problem with current practice per se that drove the project, instead it was an eagerness to encourage students to engage and collaborate with others in a similar discipline.

Table 1 Overview of collaborative projects. AR 1: Project 1 Title Theme Partners Cultural leanings Interpreting culture University of Limerick, Ireland Unitec, New Zealand AR 2: Project 2 Food for thought Food provision University of Limerick, Ireland Unitec, New Zealand Universidad de Valparaiso, Chile 32 (IRE) 17 (NZ) Designer/Client relationship between teams in each country 3 members IRE, 3 members NZ 6 Weeks Ning Twitter Teamviewer Googletalk Video Email

The primary aim of the project was to encourage effective collaboration and by this develop key competencies. These competencies have been selected from the identied list of skills and capacities necessary for designers to direct their practice towards social sustainability (as seen in Fig. 2): Development of shared skills Promotion of cultural diversity and understanding Critical analysis. Active participation Establishment of Communities of Practice; Knowledge Sharing & Networks / Interaction & engagement / Reection / Development of holistic perspectives / / / / /

4.1.1. Project brief The students, in groups of two3, were asked to identify a tradition, a cultural phenomenon or a historical practice specic to their own country. They were asked to re-imagine their chosen topic in the present day, not to rebuild the past but instead to re-interpret it in a contemporary context. The design brief never mentioned social sustainability or sustainability as these issues should not be extracted as a novelty but should be an inherent consideration in every design project. 4.1.2. Project logistics Due to the distances and time difference the students were required to make their work deliverable and communicable by available technologies. Research has shown that it is not the success of collaboration is not due to technology instead it is due to the individuals willingness and motivation to engage (Cheng and Kvan, 2000). The technology needed to be easy to use and not detract from the main aim of the project. As such each group established a blog (using Vox) and this was used as the primary communication tools for the duration of the project. The blog sites were used as virtual exhibition spaces, project management tools, reective diaries and project journals. They were also key in providing a structured platform for giving and receiving feedback from the other student participants and design tutors (Kvan, 2001). The need to share work is essential in a eld as visual as design and the blog proved essential in facilitating this. 4.1.3. Project outcomes The student work resulting from the project was both interesting and innovative. The diversity of products ranged from tattooing tools to cooking and from furniture pieces to whiskey decanters. For the rst time in their design education some groups even explored the notion of replacing the physical object with an intangible experience. 4.2. Phase 2 action research Food for thought The second phase of the action research project built on the lessons learnt from the rst phase. The project took place from the beginning of March until the end of April 2010 and initially involved three international partners: Unitec, Auckland, New Zealand;

No. of Participants Team structure

Team numbers Duration Communication tools

21 (IRE) 40 (NZ) Individual country teams partnered with team from partner country 2 members each country 6 weeks Vox Video Conferencing Email Skype

3 Two members per team was decided upon given the class sizes and the fact that the students hadnt worked on any team based design project prior to this and in order to make the management of their team and transmission of information as easy as possible (Chiu, 2002). Each team in Ireland was paired with a partner team in New Zealand to make the collaboration process more organised and manageable.

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

91

Universidad de Valparaiso, Chile and the University of Limerick, Ireland. Unfortunately due to the Chilean Earthquake disaster two weeks before the start of the project the Chilean students were unable to participate. Such unintended contingencies often form a part of Action Research as it is a continuously evolving process that is hinged on human and societal behaviour. The participant groups comprised of year 2 Product Design students from Unitec and the University of Limerick. It was a different group from that which participated in phase 1. The main modications to the second phase of the action research were in the area of the collaboration process; the depth and breadth of the collaborative experience) and the project theme. How these ndings drove subsequent changes in the second action research phase are described in Sections 4.2.2 and 5. This second project expanded the skill set for collaboration from the rst project to include the following: / / / / / Team work Compromise & negotiation Cultural and social diversity Participation Communication

larger groups. Instead of the student teams working on their own project it was decided that larger groups would be formed containing one team from each partner country. Each local team, comprising either 3/4 individuals, researched the groups sub category as it related to their country. They then handed over the research pack to another team in their group, who took the research ndings and acting as a Design team developed innovative solutions for their Client country. The designer had to refer to their clients regularly to ensure the concepts being developed were relevant and necessary. The collaboration process is mapped in Fig. 4 below. This co-generative approach allowed students to see how others approach their work (reection) and forced them to develop a common language and hone their communication skills further. It also ensured the students would not get bored of the project and the technology as easily as in the previous phase (Gross and Do, 1999). This time the student engagement with the technology would directly affect the group effort. 4.2.3. Project outcomes Once again the design outcomes from the project were interesting and diverse. Students designed a garden tool-sharing system for allotments, innovative food packaging and a tracking and monitoring system for food transportation. The design results however were not as innovative or as detailed as the previous project and the student grades reected this. This could be attributed to the fact that the students were designing for a client country and that time was required to understand the culture of this client. The interpretations of the clients research was subjective and did not necessarily reect the reality of practices within the particular client country. Conversely the design teams offered fresh eyes on the subject that the client might not have. At this stage it is worth noting that the collaboration with this project wasnt as successful as the previous one. With action research projects the failures inform the process as much as the successes so it is worthwhile noting the issues that occurred. These uneven results can be attributed to a number of factors amongst them personality differences, lack of compromise, breakdown in communication; lack of synergy and timing differences (these did not affect the rst project as much because the collaboration wasnt as deep as the 2nd project with students acting as both clients and designers). 5. Findings & discussion

4.2.1. Project brief Food was chosen as the overarching theme. Not only is it an important issue (for very different reasons) in each of the countries, but each would have a very different perspective on the subject. Again the topic is not explicitly related to sustainability; instead the students were expected to include social, environmental and economic issues in parallel with the other design considerations (e.g. human factors, functionality, aesthetics and design for manufacture). The theme was then divided into 7 sub categories including Packaging & Transport; Domestic Food Production; Community Production; Shared Dining. A longer list was initially generated by the project tutors based on trends in the areas of food and design. The list was discussed and negotiated into the list of 7 categories that the students worked with. A nding from phase 1 showed that students struggled with the open-ended theme and precious time was wasted at the start trying to come to terms with what the brief meant. It was decided to provide the students with clear direction through the more focused sub categories, while still allowing them to explore a specic area in depth. 4.2.2. Logistics A roadmap was compiled to make the collaboration as clear as possible, this signposted all the times when interaction was necessary between the groups. Twitter, Ning (this replaced the Vox platform because it offered shared forums as well as individual blogs) and Teamviewer (desktop sharing software) were introduced as communication tools to facilitate the collaboration. It was anticipated that the communication would happen outside the suggested times too so that the sharing of ideas and information could go beyond the studio and thus the broader academic environment. The ideal scenario was a move to a situation where students converse not because they have to but because they want to. The use of free and user friendly technologies facilitated more spontaneous and relaxed communication patterns to form (Cheng and Kvan, 2000). The structure of the Ning platform allowed the tutors to monitor the students use. The tutors prompted more or deeper communication on the live chat facility of the Ning when they felt the groups werent collaborating effectively, thus resolving an issue quickly that could have taken several emails previously. Another signicant change was made in the project set-up to facilitate deeper interaction between individuals, small teams and

The following section draws together both the results and discussion on the rst two phases of the action research process. This presentation better reects the iterative nature of both action research and qualitative methods (Barbour, 2008). The ndings from phase 1 drove the development of phase 2 (in continuous feedback loops) and so gathering the information and interpreting it was a parallel process. Quotes and comments from the interviews, diaries, survey responses and anecdotal conversations will provide evidence for the discussion and the conclusions drawn. Analysis of the data provided a wealth of information and observational insights. This centred on the experience of the students and the tutors which in the main was positive. The novelty of the projects really interested and engaged the students in ways that previous projects hadnt. The themes allowed them to look deeper into their own culture and society, whilst learning about the cultural inuences and traditions affecting another country. One student notes I felt it was a very good project as I learned a lot more about my culture and the elds I was researching. The project really helped my team working skills and I know that this will be really

92

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

Fig. 4. Collaboration map for phase 2.

important in the future. (Student A, survey results 5.08.08). Another stated that it was excellent to see a different culture and participate in such a project. It allows me to see beyond my own country and thoughts (Student B, survey results 5.08.08) From the design tutors perspectives the whole experience of working closely with another design school allowed them to expand their personal and professional horizons. It also provided the opportunity to explore alternative methods for preparing and implementing student projects.

5.1. Communication Blogs were used as the primary interaction tool in both projects. Despite an initial settling in period (as reected in the survey), the students not only enjoyed the novelty and convenience of this new delivery method, but they also felt that the opportunity to get feedback from others really helped and encouraged them. Being able to post work on the blog allowed for external representations of the local teams work to be available for critique, comment and

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

93

negotiation by the other members of their group (Gul and Maher, 2009).Those who did not engage fully with the blogs regretted it once the project was complete and they could review the effort exerted by their peers. In the post-project survey one student reected that I think for me the problem was being too set on designing the way I had previously, and did not interact enough with the blogging. This is something I regret as I really belief [sic] it could be used as a very useful tool (Student C, survey results 5.08.08). This atypical response from phase 1 indicated that all students would need to be encouraged and facilitated to collaborate more during the 2nd project. 5.2. Interaction The ability to view the work of all the students (via blog neighbourhoods) put pressure on the students to increase the standard of their work as now direct and immediate comparisons could be drawn between the work of the various individuals, teams and groups. A student stated that [It].made me see the standard at which my projects need to reach (Student D, survey results 5.08.08). Another observed that it was benecial in terms of getting advice from other students, because our work was going to be seen by a lot of people it forced me to strive for a high standard of work (Student E, survey results 5.08.08). These views were conrmed by the students during interview, they felt that because the comparisons were clear on the blog they tried harder to raise their work standard. In the survey one student noted that it was a good way to see what other people were up too and to look for inspiration (Student F, survey results 5.08.08). The interviews corroborated these statements. Student 1: we thought the standard of work compared to previous projects level just went way higher. Researcher: why do you think that was? Student 1: I think its competition, because you have that other group and you know they have a long history of design and we are just very new, so we just wanted to make sure we matched their standard and were better. (Student 1, group 1, interview 26.02.10) In addition because the blogs could be updated in real-time this reection tended to be more honest than if time was allowed to think on the comments. One student positively observed that the blogs provided them with a better understanding of presenting digitally and also great for gaining techniques and sharing ideas with a different design course (Student G, survey results 5.08.08). 5.2.1. Insights A very positive by-product from using blogs is that a permanent record of the work is retained that can be accessed on an on-going basis. The video conferences allowed the students to meet each other and relate a face to the virtual relationship that had previously existed. Enjoyment from the video conferences was obvious at the time and the feedback afterwards conrmed as much. There was a suggestion, however that a video conference at the start of the project would be benecial so the students could be introduced to each other and this might lead to a greater degree of interaction via the blogs throughout the remainder of the project. One student suggested a preference to maybe meet at the start like we did at the end would be good to create a bond (Student 5, group 3, interview 26.02.10). This change was introduced in the second phase where students scheduled formal and informal virtual meetings at regular stages in the project. Not all feedback was positive however. Some students felt the blogs werent a benecial component of the project and as such their engagement with their local team-mates and partner teams

did not reach a deep or mutually benecial level. Some also felt that if their interaction wasnt reciprocated they were less inclined to use the blog as the project progressed e.g. we tried but when we werent receiving anything back we just gave up (Student 3, group 2, interview 26.02.10). As with every project some students will engage more, ask for more feedback and enjoy the overall experience more. Working with another country would be very good it just turned out that there was not much communication inputs and so on (as far as I experienced it) (Student 4, group2, interview 26.02.10). This observation ensures a deeper and perhaps more forced interaction between the participating countries was necessary in the 2nd phase project. Subsequent phases of the project will endeavour to deepen the collaboration and also explore how participation in the projects will inuence the behaviour of designers once they are qualied professionals. 5.3. Reective practice The opportunity for reection was provided in two ways in the project; local reection on their work with the project and distant reection on the work and processes of the partner country. Students reected not only on their work but on their individual practice and their learning experience. The overall depth of information appearing on the blogs conrmed that students reected more and at greater length about their work I think it was more interesting to see other peoples work. There was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing between us and New Zealand and it was really interesting to see their work and see new sketches and stuff. It was nice to compare because sometimes you just get lost in here [UL design studio] your own class and how you compare with them (Student 6, group 3, interview 26.02.10). There were a few exceptions however when some students did not engage with the project theme and the software as much as other students. Reection is a key part of design work, but it tends to come at the end of the project. The real-time nature of the blogging process ensured the students reected instantly on their design work, forcing them to question and justify the decisions they were making, as they were making them. This is something often missing from conventional projects as limited time and tight delivery requirements mitigate against continuous reection on their own practice (students are encouraged to reect on their outputs but not always on their individual practice). 5.4. Engagement Students engaged with the projects more readily than with conventional projects, resulting in better outcomes and a higher quality of work, thus creating a deeper learning experience. The dimension of having the other country there pushed us to get a more professional product and professional nish. Before there wasnt that real drive but with them there we were looking at their work and saying we can do this and we can push things a little bit further (Student 2, group 1, interview 26.02.10). However some measures could be taken in future projects to ensure greater engagement with the project and the interactions from all students participating. These could include (but are not limited to) additional formal video conferencing sessions, provide facilities for more informal dialogues between student teams, better collaboration through shared project deliverables between different countries. 5.5. Developing critical thinking Students began to question their own practices and those of other cultures through the projects. This type of critical experience encourages deeper learning that can prove to be transformative in

94

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

the students education. This was evidenced through the projects as the students had begun to analyse, synthesise, and evaluate their own work (Ennis, 1993). They also felt encouraged to look closely at the work of the other teams and comment critically on it. The blogging platforms encouraged them to share their ideas It [the project] made you think more outwardly, if you have a project [you] dont just think on that particular one thing (Student 8, group 4, interview 26.02.10) they could take a completely outside look at our product and give us advice (Student 4, group 2, interview 26.02.10). From the analysis of phase 1 it was apparent that the opportunity for critical analysis needed to be developed further in phase 2. At the start of the 2nd project each group made a video introducing their group and then a video conference was held (as was suggested in phase 1). This ensured that the interaction went beyond professional and the relationship moved onto personal. In addition an attitudinal survey was completed by the students prior to the beginning of phase 2. This was to assess their level of knowledge about certain skills and aspects related to social sustainability and collaboration. The results from this survey will be explored through the next AR phase to assess whether the attitudes and behaviours have evolved after completing the phase 2 (the students from phase 2 are scheduled to be interviewed in the coming months).As well the participants from phase 1 will be interviewed again (they have since graduated), as critical thinking skills take time to learn and to manifest in project work (Ennis, 1993). 5.6. Broader perspectives By participating in this type of project the students gained an understanding of what drives design in other countries (both historical and contemporary inuences). One student clearly saw that its quite similar to Irish, they have the same humour. get a new perspective on design and how other design courses are doing it. I suppose its kind of reassuring that we are not too far off (Student 6, group 3, interview 26.02.10). Also another noted that .its very similar but they just had a different slant on things, a bit of a twist (Student 5, group 3 interview 26.02.10). This gave the students an understanding that design does not occur in a vacuum and that society is both inuenced by and inuences design practice. This can be a difcult concept to relate to students and is best learnt by engagement with a diverse group of project partners. On this premise the group of participating countries should be expanded to include designers from different socio-economic backgrounds and varied cultural models. 5.7. Confusion & conict Collaboration wasnt always successful unfortunately in spite of positive attitude and initial enthusiasm. Success was uneven between the two projects given the contingencies in running such projects. In spite of all the paths being clearly laid out the situations did not always play out as predicted. Human behaviour is such that it cannot be controlled on every level, nor indeed should it be as the spontaneous outcomes often prove the most interesting. The downside to collaboration became apparent in the AR 2 as the project broke-down and resistance increased in the latter stages. This can be attributed to cultural differences and a mismatch of goals and methods (Lozano, 2006). The differences in cultures between team members meant trust wasnt established as quickly as it needed to be for the project to work within the limited timeframe (McDonough et al., 2001). From a more practical level the incompatible time-zones and academic calendars made the physical communication difcult throughout both projects.

Although more time had been given to planning and working out logistics in phase 2 the lack of clear shared goals, distributed responsibilities, conicting agendas and equal involvement of stakeholders (Fadeeva, 2004) led to less successful project outcomes and experience. These conicts should not always be viewed as a negative thing however, as they were benecial in allowing different views to be aired and compared. Negotiating these conicts helped the students to develop key skills of compromise and effective communication and encouraged students to be innovative to nd ways of resolving them (Fadeeva, 2004). The issue of managing the conicts and the negotiation of goals will be given particular attention in the coming AR phases. The researcher intends to explore the notions of synergy (working towards an agreed common goal) and commitment (or buy-in) within subsequent phases, where the agendas are negotiated and agreed on prior to the project. 6. Conclusion Sustainable development calls for every profession to behave more responsibly and also to become more globally aware. The expectation on designers to practice more responsibly is coming from industry, government and society. Yet designers are not being equipped with the skills and competencies necessary to do this. Social sustainability by its nature difcult to implement in design practice as it deals with softer and immeasurable elements of human and societal behaviour. The aim of this research has been to clearly identify a core set of skills and competencies that designers need to be able to work effectively with others in solving the wicked problems that social sustainability presents. Collaborative projects bring greater engagement and therefore encourage the acquisition and development of these skills and competencies. These have been identied to include participation, openness, dialogue, reection, participation, engagement, understanding, cooperation and compromise. By encouraging knowledge sharing and critical thinking the participating design students have begun to reect on their behaviour and the behaviour of others. The two phases of the Action Research (AR) project described above explored how exposure to multiple perspectives in the denition and resolution of design problems can broaden the educational experience for students. Looking at effective group collaborations, sharing knowledge and the development of individual skills (such as critical analysis and reection) in phase 1 revealed that for students to engage and participate fully, communication, the building of trust and the ability to compromise and negotiate with team members needed to be developed further. Phase 2 of the AR process expanded the project to include the development and practising of these additional competencies. The ndings suggest that students have begun to develop a set of skills that will enable them to effectively collaborative in projects that can begin to address the challenges of sustainability from a global perspective. The experience of undertaking the two collaborative projects has shown that, by exposure to diversities of practice, behaviours and perspectives, designers can begin to engage with the complex theory behind social sustainability in a real and practical way. Therefore the focus in the student designers work needs to be on the development of exible tools and transferrable skills. Skills that ensure they become adaptive professionals who can collaborate effectively across distances and disciplines. The reection on and outcomes from these experimental and exploratory projects will hopefully serve students to nd empathy, common ground and a common language in solving and resolving the issues surrounding social sustainability. Care

M. McMahon, T. Bhamra / Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (2012) 86e95

95

must be taken not to generalise the results however as the Action Research approach means that the results are project specic with the samples small and focused. While the success of the projects has been varied the ndings from the two described in this paper demonstrates that participation in the projects can bring about subsequent changes in the design students practice. The design and implementation of future projects needs to be further developed and improved and this will be carried out in subsequent phases of the Action Research process. Further research into the longer term impact of these projects on design students must be done in order to understand the benets to their practice post-graduation. The projects described above have gone some way to encouraging design students to collaborate and engage across social and geographical boundaries. The very process of undertaking them has highlighted the real and apparent need for designers to develop the range of skills that ensure responsible practice becomes normative. As the realm of professional design shifts towards a future of alternative systems students must develop the ability to think pragmatically, innovatively and holistically.

References

Barbour, R., 2008. Introducing Qualitative Research: a Student Guide to the Craft of Doing Qualitative Research. SAGE, London. Baskerville, R.L., Wood-Harper, A.T., 1996. A critical perspective on action research as a method for information systems research. Journal of Information Technology 11, 235e246. Bhamra, T., Dewberry, E., 2007. Re-visioning design priorities through sustainability education. In: International Conference on Engineering Design, ICED07, 28e31 August 2007. Bramley, G., Dempsey, N., Power, S., Brown, C., 2006. What is Social Sustainability, and how do our existing urban forms perform in nurturing it?. In: Planning Research Conference. UCL, London, p. 40. Bremer, M.H., Lpez-Franco, R., 2006. Sustainable development: ten years of experiences at ITESMs graduate level. Journal of Cleaner Production 14 (9e11), 952e957. Burns, C., Cottam, H., Vanstone, C., Winhall, J., 2006. RED Paper 02: Transformation Design, Design Council. Cassimir, G., Dutilh, C., 2003. Sustainability: a gender studies perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies 27 (4), 316e325. Chapman, J., 2005. Emotionally Durable Design; Objects, Experience & Empathy. Earthscan, London. Cheng, N. Y.-w., Kvan, T., 2000. Design collaboration strategies. In: 4th SIGRADI, Rio de Janeiro. Chiu, M.-L., 2002. An organizational view of design communication in design collaboration. Design Studies 23, 187e210. Core77, 2010. The Design Matters Concentration at Art Center College of Design: Q&A with Mariana Amatullo Available: www.core77.com/ [accessed 15.12.2010]. Cumming, M., Akar, E., 2005. Coordinating the complexity of design using P2P groupware. CoDesign 1 (4), 255e265. Design Council, 2006. RED [online], Available: http://www.designcouncil.info/RED/ [accessed]. Designophy, 2001. Dening the Designer of 2015, Design Knowledge Intermediary Available: www.designophy.com/ [accessed 10.1.11]. Dewberry, E.L., 1996. Eco-Design: Present attitudes and future directions. Unpublished Thesis Open University. Ennis, R.H., 1993. Critical thinking assessment. Theory Into Practice 32 (3), 179e186. Fadeeva, Z., 2004. Promises of sustainability collaboration- potential fullled? Journal of Cleaner Production 13, 165e174. Findeli, A., 2008. Sustainable design: a critique of the current tripolar model. The Design Journal 11 (3), 301e322. Fletcher, K., Dewberry, E., 2002. Demi: a case study in design for sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 3 (1), 38e47. Gonzlez-Gaudiano, E., 2005. Education for sustainable development: conguration and meaning. Policy Futures in Education 3 (3), 243e250. Gross, M., Do, E., 1999. Integrating Digital Media in design studio: Six Paradigms. In: Proc. ACSA (American Collegiate Schools of Architecture) National Conference Minneapolis.

Gul, L.F., Maher, M.L., 2009. Co-creating external design representations: comparing face-to-face sketching to designing in virtual environments. Co Design 5 (2), 117e138. Hara, K., 2009. Designing Design. Lars Muller Publishers, Eindhoven. Jegou, F., Manzini, E., 2008. Collaborative Services: Social Innovation and Design for Sustainability Edizioni Poli. Design [online], available: [accessed]. Jupp, V. (Ed.), 2006. The SAGE Dictionary of Social Research Methods. SAGE Publications Ltd, London. Krull, P., 2010. Social Innovation Available: [accessed 11.05.10]. Kvan, T., 2001. The pedagogy of virtual design studios. Automation in Construction 10, 345e353. Lawson, B., 2006. How Designers Think: The Design Process Demystied, 4 ed. Architectural, Amsterdam London. Lilley, D., 2007. Designing for Behavioural Change: Reducing the Social Impacts of Product Use through Design. Unpublished Thesis, Loughborough University. Loughran, J.J., 2002. Effective reective practice: in search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education 53 (33). Lozano Garca, F., Kevany, K., Huisingh, D., 2006. Sustainability in higher education: what is happening? Journal of Cleaner Production 14 (9e11), 757e760. Lozano, R., 2006. Incorporation and institutionalization of SD into universities: breaking through barriers to change. Journal of Cleaner Production 14 (9e11), 787e796. Lozano, R., 2007. Collaboration as a pathway for sustainability. Sustainable Development 15, 370e381. Manzini, E., 2007. Design research for sustainable social innovation. In: Michel, R. (Ed.), Design Research Now: Essays and Selected Projects. Birhauser, Basel. Manzini, E., 2009a. Design Research for Sustainable Social Innovation Available: http://www.sustainable-everyday.net/manzini/ [accessed 11.10.09]. Manzini, E., 2009b. Viewpoint new design knowledge. Design Issues 30 (1), 4e12. Manzini, E., 2010. Small, local, open and connected: design for social innovation and sustainability. The Journal of Design Strategies 4 (1), 8e11. McDonough, E.F.I., Kahn, K.B., Barczak, 2001. An investigation of the use of global, virtual and colocated new product development teams. The Journal of Product Innovation Management 18, 110e120. McDowell, L., Smailes, J., Sambell, K., Sambell, A., Wakelin, D., 2008. Evaluating assessment strategies through collaborative evidence-based practice: can one tool t all? Innovations in Education and Teaching International 45 (2), 143e153. McKenzie, S., 2004. Social sustainability: towards some denitions. In: Hawke Research Institute Working Papers Series Available: [accessed]. McKeown, R., 2002. Education for Sustainable Development Toolkit, 2. University of Tennessee, Tennessee. McNiff, J., Whitehead, J., 2006. All You Need to Know about Action Research. SAGE Publications Ltd, , London. Mendoza, A., 2010. DESIS Newsletter 0: A Catalyzing Agent. DESIS. Moore, F.C., 2011. Toppling the tripod: sustainable development, constructive ambiguity and the environmental challenge. Consilience: The Journal of Sustainable Development 5 (1), 141e150. Moritz, S., 2005. Service Design: Practical Access to an Evolving Field. Unpublished Thesis, University of Applied Sciences Cologne. Murray, R., Mulgan, G., Caulier-Grice, J., 2010. How to Innovate: The Tolls for Social Innovation. The Young Foundation. Nelson, H.G., Stolterman, E., 2003. The Design Way: Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World. Educational Technology Publications, New Jersey. Segalas, J., Ferrer-Balas, D., Mulder, K.F., 2010. What do engineering students learn in sustainability courses? The effect of the pedagogical approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 18, 275e284. Sherwin, C., 2004. Design and sustainability: a discussion paper based on personal experience and observations. The Journal of Sustainable Product Design 4, 21e31. Spangenberg, J.H., Fuad-Luke, A., Blincoe, K., 2010. Design for Sustainability (DfS): the interface of sustainable production and consumption. Journal of Cleaner Production 18, 1485e1493. Steiner, G., Posch, A., 2006. Higher education for sustainability by means of transdisciplinary case studies: an innovative approach for solving complex, realworld problems. Journal of Cleaner Production 14 (9e11), 877e890. Sterling, S., 2001. Sustainable Education: Re-Visioning Learning and Change. Schumacher Society, Devon. Thackara, J., 2006. In the Bubble: Designing in a Complex World. MIT Press, Cambridge. UN, E. a. S. C, 2005. UNECE Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development. United Nations, Vilinius. UNESCO, 2004. United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development: Draft International Implementation Scheme (IIS). United Nations Educational, Scientic and Cultural Organisation, Paris. Walker, S., 2006. Sustainable by Design. Earthscan. Earthscan. Whiteley, N., 1993. Design for Society. Reaktion Books, London.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Problem-Oriented and Project-Based Learning (POPBL) As An Innovative Learning Strategy For Sustainable Development in Engineering EducationDocument14 paginiProblem-Oriented and Project-Based Learning (POPBL) As An Innovative Learning Strategy For Sustainable Development in Engineering EducationulisesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Education in Design For Sustainability and New Social ChangesDocument6 paginiEducation in Design For Sustainability and New Social Changestj.shirleysunÎncă nu există evaluări

- C. Stevenson (Sample - Indexed Articles On Architectural Education)Document88 paginiC. Stevenson (Sample - Indexed Articles On Architectural Education)Carolina RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Definition of Architecture From Famous Architects:: Caroline BosDocument15 paginiDefinition of Architecture From Famous Architects:: Caroline BosSaba HajizadehÎncă nu există evaluări

- Problem-Oriented and Project-Based Learning (POPBL) As An Innovative Learning Strategy For Sustainable Development...Document15 paginiProblem-Oriented and Project-Based Learning (POPBL) As An Innovative Learning Strategy For Sustainable Development...Taitusi BiciÎncă nu există evaluări

- Challenge Driven Education in The Context of Internet of ThingsDocument6 paginiChallenge Driven Education in The Context of Internet of Thingspantzos.stockholm.suÎncă nu există evaluări

- Social Sciences & Humanities Open: R. Shanthi Priya, P. Shabitha, S. RadhakrishnanDocument12 paginiSocial Sciences & Humanities Open: R. Shanthi Priya, P. Shabitha, S. RadhakrishnanDAVIE KEITH PASCUAÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2019 Yeoman Carvalho Moving Between Mayerial ACDADocument26 pagini2019 Yeoman Carvalho Moving Between Mayerial ACDApacoperez2008Încă nu există evaluări

- Cultivating The Next Generation Designers: Group Work in Urban and Regional Design EducationDocument20 paginiCultivating The Next Generation Designers: Group Work in Urban and Regional Design Educationwen zhangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 8Document12 paginiModule 8riza cabugnaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Slactions2010 - User Involvement in The Design of Educational Virtual WorldsDocument4 paginiSlactions2010 - User Involvement in The Design of Educational Virtual WorldsResearch conference on virtual worlds – Learning with simulationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Architecture at The Edge of Practice: A Pedagogical Approach To Social Architectural EducationDocument7 paginiArchitecture at The Edge of Practice: A Pedagogical Approach To Social Architectural EducationKayfi Akram MawlanÎncă nu există evaluări

- This Work Is Licensed Under A Creative CDocument8 paginiThis Work Is Licensed Under A Creative CCarlos GuerraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mind The Gap: Co-Created Learning Spaces in Higher EducationDocument15 paginiMind The Gap: Co-Created Learning Spaces in Higher Educationvpvn2008Încă nu există evaluări

- s2 Paper2Document9 paginis2 Paper2XÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inclusive Design For Immersive SpacesDocument15 paginiInclusive Design For Immersive SpacesMark Terrence EnanoriaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design Thinking As An Approach To Guide A More Humanized Learning Process in Engineering TeachingDocument13 paginiDesign Thinking As An Approach To Guide A More Humanized Learning Process in Engineering TeachingIJAERS JOURNALÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Five Resources of Critical Digital Literacy: A Framework For Curriculum IntegrationDocument16 paginiThe Five Resources of Critical Digital Literacy: A Framework For Curriculum IntegrationLouize MouraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Integrating Sustainability Into Design Education: The ToolkitDocument23 paginiIntegrating Sustainability Into Design Education: The ToolkitPablo AlarcónÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainability 12 07397 v2 PDFDocument14 paginiSustainability 12 07397 v2 PDFMelissa Ann PatanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vegahamilton ChangeagentprojectDocument10 paginiVegahamilton Changeagentprojectapi-622958425Încă nu există evaluări

- Research Statement Generic 10 2014Document4 paginiResearch Statement Generic 10 2014api-267216248Încă nu există evaluări

- Teachers As Participatory Designers: Two Case Studies With Technology-Enhanced Learning EnvironmentsDocument26 paginiTeachers As Participatory Designers: Two Case Studies With Technology-Enhanced Learning EnvironmentsFollet TortugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- James Waller - Pme 832 - Culminating Task RationaleDocument5 paginiJames Waller - Pme 832 - Culminating Task Rationaleapi-450537948Încă nu există evaluări

- Water Project: Computer-Supported Collaborative E-Learning Model For Integrating Science and Social StudiesDocument14 paginiWater Project: Computer-Supported Collaborative E-Learning Model For Integrating Science and Social StudiesAlibai Ombo TasilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Goodyear 2005 Educational Design and Networked LearningDocument20 paginiGoodyear 2005 Educational Design and Networked Learningpacoperez2008Încă nu există evaluări

- Environmental Science and Sustainable DevelopmentDocument17 paginiEnvironmental Science and Sustainable DevelopmentIEREKPRESSÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research, Development, Diffusion and Social Interaction ModelsDocument13 paginiResearch, Development, Diffusion and Social Interaction ModelsSimon FillemonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Critical Reflection in Community Work Education: A Social Work Curriculum Addressing Social Deprivation and PovertyDocument15 paginiCritical Reflection in Community Work Education: A Social Work Curriculum Addressing Social Deprivation and Povertybeck827Încă nu există evaluări

- Literacies of Design: Studies of Equity and Imagination in Engineering and MakingDe la EverandLiteracies of Design: Studies of Equity and Imagination in Engineering and MakingAmy Wilson-LopezÎncă nu există evaluări

- MultidisciplinaridadeDocument22 paginiMultidisciplinaridadeRodrigo Leme da SilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Konektivisme 1261Document6 paginiKonektivisme 1261Wahyu DiantoroÎncă nu există evaluări

- DBRC 2003 An Emerging Paradigm For Educational InquiryDocument5 paginiDBRC 2003 An Emerging Paradigm For Educational InquiryJoshua RuhlesÎncă nu există evaluări

- CSCL2023 378-379Document2 paginiCSCL2023 378-379Chris PetrieÎncă nu există evaluări

- EJ1352505Document10 paginiEJ1352505karenarb93Încă nu există evaluări

- A.Loveless Et Al. - Developing Conceptual Frameworks For Creativity, ICT and Teacher EducationDocument11 paginiA.Loveless Et Al. - Developing Conceptual Frameworks For Creativity, ICT and Teacher EducationBillekeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning Integrative ThinkingDocument9 paginiLearning Integrative ThinkingMichael AndrewsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Transformative Learning in Architectural Education - TransARK - Intetral Theory and IPMDocument10 paginiTransformative Learning in Architectural Education - TransARK - Intetral Theory and IPMMariaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 23 - Breaking BadDocument13 pagini23 - Breaking BadpsychonetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assessment For Learning in Primary Technology ClasDocument10 paginiAssessment For Learning in Primary Technology ClasYunita SafitriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Participatory Educational Design: Citation For Published Version (APA)Document13 paginiParticipatory Educational Design: Citation For Published Version (APA)Follet TortugaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student Participation in Engineering Practices and Discourse: An Exploratory Case StudyDocument22 paginiStudent Participation in Engineering Practices and Discourse: An Exploratory Case StudyAlex Samuel SilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- K Donahue Assignment Two Edam 528Document7 paginiK Donahue Assignment Two Edam 528api-262204481Încă nu există evaluări

- Sustainability 11 05247Document24 paginiSustainability 11 05247Mohola Tebello GriffithÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interdisciplinary Education A Case StudyDocument19 paginiInterdisciplinary Education A Case Studymadeline bebarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Participatory Design For Sustainable Social Change: July 2018Document29 paginiParticipatory Design For Sustainable Social Change: July 2018dpcsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Eth Noh Tec HandoutDocument13 paginiEth Noh Tec HandoutbarrackÎncă nu există evaluări

- Curriculum, Instructional Design and The Technologies Planning For Educational DeliveryDocument13 paginiCurriculum, Instructional Design and The Technologies Planning For Educational Deliveryziyad fauziÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching Competencies For The 21st CentuDocument5 paginiTeaching Competencies For The 21st CentuShikha MaheshwariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 1Document8 paginiAssignment 1mustafe xagarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ad ResearchDocument13 paginiAd ResearchBea Jemifaye AndalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abdullah Et Al. - 2011 - Architecture Design Studio Culture and Learning Spaces A Holistic Approach To The Design and Planning of LearniDocument6 paginiAbdullah Et Al. - 2011 - Architecture Design Studio Culture and Learning Spaces A Holistic Approach To The Design and Planning of LearniMarcelo PintoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aalborg Universitet: The Role of Theory of ChangeDocument14 paginiAalborg Universitet: The Role of Theory of ChangeIctus7 CreativusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Designing Opportunities Transformation Emerging TechnologiesDocument10 paginiDesigning Opportunities Transformation Emerging Technologiesapi-316863050Încă nu există evaluări

- Space To Reflect Combinatory Methods For PDFDocument18 paginiSpace To Reflect Combinatory Methods For PDFsebastian castroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainability in The Future of D - 2023 - She Ji The Journal of Design EconomDocument22 paginiSustainability in The Future of D - 2023 - She Ji The Journal of Design EconomJoão SantosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Convergence and Divergence in Engineering Education in AfricaDocument10 paginiConvergence and Divergence in Engineering Education in AfricaTJPRC PublicationsÎncă nu există evaluări

- DBR WjetDocument9 paginiDBR WjetYusrin RezaÎncă nu există evaluări

- (8-12) Developing Teaching Material For E-Learning EnvironmentDocument5 pagini(8-12) Developing Teaching Material For E-Learning EnvironmentiisteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Learning While Creating Value For Sustainability Transitions: The Case of Challenge Lab at Chalmers University of TechnologyDocument10 paginiLearning While Creating Value For Sustainability Transitions: The Case of Challenge Lab at Chalmers University of TechnologyabarroqueiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business Analysis ToolsDocument147 paginiBusiness Analysis ToolsNishant GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Green Habitat May 2011Document2 paginiGreen Habitat May 2011Nishant GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Biofuels of IndiaDocument18 paginiBiofuels of IndiaNishant GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Can We Explain Airport PerformanceDocument5 paginiCan We Explain Airport PerformanceNishant GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analytic Hierarchy Process - An Overview of ApplicationsDocument29 paginiAnalytic Hierarchy Process - An Overview of ApplicationsvirenderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sima Pro 7 Introduction To LCADocument88 paginiSima Pro 7 Introduction To LCANishant GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- File1-Unit 1 (A)Document54 paginiFile1-Unit 1 (A)Nishant GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Toyota Way20060913024959Document4 paginiThe Toyota Way20060913024959Nishant GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Write A Curriculum Vitae in FrenchDocument4 paginiHow To Write A Curriculum Vitae in FrenchRosyi ChanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research Proposal by DR J R SonwaneDocument83 paginiResearch Proposal by DR J R Sonwaneeresearch1976Încă nu există evaluări

- 4nbt1 Assessmenttask 4Document3 pagini4nbt1 Assessmenttask 4api-280863641Încă nu există evaluări

- Mathematics 1 - Q3 - W1 - DLLDocument6 paginiMathematics 1 - Q3 - W1 - DLLVince Andrew OrdenesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technology Enhanced Learning Environments - HealeyDocument6 paginiTechnology Enhanced Learning Environments - HealeyPenny100% (1)

- Iec Obg CareDocument18 paginiIec Obg Carenaga mani100% (1)

- Career Preparedness and Employability Skills of Hospitality StudentsDocument11 paginiCareer Preparedness and Employability Skills of Hospitality Studentsvinay kumar100% (1)

- Teaching Guide Catchup AP Peace Ed FormatDocument8 paginiTeaching Guide Catchup AP Peace Ed FormatJOHN LEMUEL NOCHEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classroom Instruction Delivery Alignment Map (CIDAM) : Semester-1Document4 paginiClassroom Instruction Delivery Alignment Map (CIDAM) : Semester-1Mary-Rose Casuyon100% (1)

- Prof Ed2-Module 1 Darlene MayladDocument8 paginiProf Ed2-Module 1 Darlene MayladJayson BarajasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Platt CV March13Document6 paginiPlatt CV March13Julie AlexanderÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fce Speakings Examples For ExamDocument24 paginiFce Speakings Examples For ExamPaula Clavijo MillanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management Practices QuestionnaireDocument4 paginiManagement Practices QuestionnaireEm Ty100% (4)

- [Education in the Asia-Pacific Region_ Issues, Concerns and Prospects 36] Matthew J. Schuelka, T.W. Maxwell (eds.) - Education in Bhutan_ Culture, Schooling, and Gross National Happiness (2016, Springer Singapore).pdfDocument264 pagini[Education in the Asia-Pacific Region_ Issues, Concerns and Prospects 36] Matthew J. Schuelka, T.W. Maxwell (eds.) - Education in Bhutan_ Culture, Schooling, and Gross National Happiness (2016, Springer Singapore).pdfJosé Augusto RentoÎncă nu există evaluări

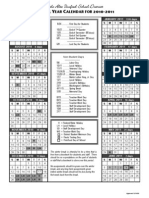

- PAUSD SchoolYearCalendar2010Document1 paginăPAUSD SchoolYearCalendar2010Justin HolmgrenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nursing Students Perceptions of Desirable Leadership Qualities in NurseDocument15 paginiNursing Students Perceptions of Desirable Leadership Qualities in NurseRereÎncă nu există evaluări

- Co Lesson Plan English 3 Quarter 3Document6 paginiCo Lesson Plan English 3 Quarter 3Nerissa HalilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Management A Practical Introduction 9E 9Th Edition Angelo Kinicki Download PDF ChapterDocument51 paginiManagement A Practical Introduction 9E 9Th Edition Angelo Kinicki Download PDF Chapterandre.trowbridge312100% (10)

- Probability of Mutually and Non Mutually Exclusive Events 1Document64 paginiProbability of Mutually and Non Mutually Exclusive Events 1syron anciadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan For Scientific MethodDocument3 paginiLesson Plan For Scientific MethodUriah BoholstÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2017 Teaching ResumeDocument2 pagini2017 Teaching Resumeapi-338727773Încă nu există evaluări

- Kertas Kerja Cadangan Kajian TindakanDocument6 paginiKertas Kerja Cadangan Kajian TindakanJay Hanafiah100% (1)

- Least Learned Grade 6Document3 paginiLeast Learned Grade 6Danilo Landicho jrÎncă nu există evaluări

- CAMBRIDGE - ENDORSED Low Res Final PDFDocument7 paginiCAMBRIDGE - ENDORSED Low Res Final PDFAnonymous fZ93HP4UYgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mfat and Ppst-Rpms Implementation: School Learning Action CellDocument27 paginiMfat and Ppst-Rpms Implementation: School Learning Action CellSonny MatiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- HTTPS: Core - Myblueprint.ca HighSchool Plan CsmPrintDocument2 paginiHTTPS: Core - Myblueprint.ca HighSchool Plan CsmPrintmustafa warsameÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 6 1 EnglishDocument142 paginiModule 6 1 EnglishChanzkie LlagunoÎncă nu există evaluări

- ALD Academic Language Development 2Document13 paginiALD Academic Language Development 2ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fullerton Problem Solving 101 Pre ReadingDocument3 paginiFullerton Problem Solving 101 Pre ReadingSowmya KartikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trainers MethodologyDocument3 paginiTrainers MethodologyPamela LogronioÎncă nu există evaluări

![[Education in the Asia-Pacific Region_ Issues, Concerns and Prospects 36] Matthew J. Schuelka, T.W. Maxwell (eds.) - Education in Bhutan_ Culture, Schooling, and Gross National Happiness (2016, Springer Singapore).pdf](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/387019616/149x198/cf714dc69d/1535201024?v=1)