Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Support Locations

Încărcat de

dasubhaiDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Support Locations

Încărcat de

dasubhaiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

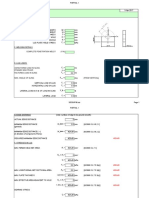

NPS

1 2 3 4 6 8 12 16 20

Water Service 2.1 3.0 3.7 4.3 5.2 5.8 7.0 8.2 9.1

Steam, Gas Air Service 2.7 4.0 4.6 5.2 6.4 7.3 9.1 10.7 11.9

GENERAL NOTES:

Suggested maximum spacing between pipe supports for horizontal straight runs of standard and heavier pipe at maximum operating temperature of 750F (400C)

Does not apply where span calculations are made or where there are concentrated loads between supports, such as flanges, valves, specialties, etc.

The spacing is based on a fixed beam support with a bending stress not exceeding 2,300 psi (15.86 MPa) and insulated pipe filled with water or the

24

9.8

12.8

equivalent weight of steel pipe for steam, gas, or air service, and the pitch of the line is such that a sag of 0.1 in. (2.5 mm) between supports is permissible.

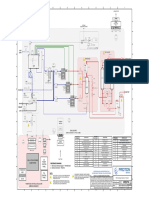

SUPPORT LOCATIONS

The locations of piping supports are dependent upon four factors: pipe size, piping configuration, locations of valves and fittings, and the structure available for support. Individual piping materials have independent considerations for span and placement of supports.

Pipe size relates to the maximum allowable span between pipe supports. Span is a function of the weight that the supports must carry. As pipe size increases, the weight of the pipe also increases. The amount of fluid which the pipe can carry increases as well, thereby increasing the weight per unit length of pipe.

The configuration of the piping system affects the location of pipe supports. Where practical, a support should be located adjacent to directional changes of piping. Otherwise, common practice is to design the length of piping between supports equal to, or less than, 75% of the maximum span length where

changes in direction occur between supports. Refer to the appropriate piping material chapters for maximum span lengths.

Valves require independent support, as well as meters and other miscellaneous fittings. These items contribute concentrated loads to the piping system. Independent supports are provided at each side of the concentrated load.

Location, as well as selection, of pipe supports is dependent upon the available structure to which the support may be attached. The mounting point shall be able to accommodate the load from the support. Supports are not located where they will interfere with other design considerations. Some piping materials require that they are not supported in areas that will expose the piping material to excessive ambient temperatures. Also, piping is not rigidly anchored to surfaces that transmit vibrations. In this case, pipe supports isolate the piping system from vibration that could compromise the structural integrity of the system.

Spacing is a function of the size of the pipe, the fluid conveyed by piping system, the temperature of the fluid and the ambient temperature of the surrounding area.

Determination of maximum allowable spacing, or span between supports, is based on the maximum amount that the pipeline may deflect due to load. Typically, a deflection of 2.5 mm is allowed, provided that the maximum pipe stress is limited to 1,500 psi or allowable design stress divided by a safety factor of 415, whichever is less. Some piping system manufacturers and support system manufacturers have information for their products that present recommended spans in tables or charts. These data are typically empirical and are based upon field experience.

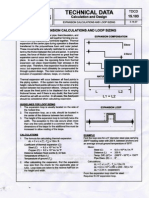

PIPE SPAN CHARTS

Pipe Span Charts are very nice, but not more than a guide. I've seen several tables and charts, all with different values. You should consider the material used, wall thickness, density of the medium, isolation, etc.. For really good assessment of working stresses and deflections, pipe stress calculations are needed. Also, the engineer must be determine what kind of support he wants to use. Should there be limits to

the movements, or even a fixed point etc. etc.. Supporting is a profession.

Allowance for expansion

All pipes will be installed at ambient temperature. Pipes carrying hot fluids such as water or steam operate at higher temperatures. It follows that they expand, especially in length, with an increase from ambient to working temperatures. This will create stress upon certain areas within the distribution system, such as pipe joints, which, in the extreme, could fracture. The amount of the expansion is readily calculated using Equation 10.4.1, or read from an appropriate chart such as Figure 10.4.1. Equation 10.4.1 Where: L = Length of pipe between anchors (m) T = Temperature difference between ambient temperature and operating temperatures (C) -3 = Expansion coefficient (mm/m C) x 10

10.4.1 Expansion coefficients (a) (mm/m C x 10 )

-3

Table

Example 10.4.1

A 30 m length of carbon steel pipe is to be used to transport steam at 4 bar g (152C). If the pipe is installed at 10C, determine the expansion using Equation 10.4.1.

Alternatively, the chart in Figure 10.4.1 can be used for finding the approximate expansion of a variety of steel pipe lengths - see Example 10.4.2 for explanation of use.

Example 10.4.2

Using Figure 10.4.1. Find the approximate expansion from 15C, of 100 metres of carbon steel pipework used to distribute steam at 265C. Temperature difference is 265 - 15C = 250C.

Where the diagonal temperature difference line of 250C cuts the horizontal pipe length line at 100 m, drop a vertical line down. For this example an approximate expansion of 330 mm is indicated.

Fig. 10.4.1 A chart showing the expansion in various steel pipe lengths at various temperature differences

Table 10.4.2 Temperature of saturated steam Top

Pipework flexibility

The pipework system must be sufficiently flexible to accommodate the movements of the components as they expand. In many cases the flexibility of the pipework system, due to the length of the pipe and number of bends and supports, means that no undue stresses are imposed. In other installations, however, it will be necessary to incorporate some means of achieving this required flexibility. An example on a typical steam system is the discharge of condensate from a steam mains drain trap into the condensate return line that runs along the steam line (Figure 10.4.2). Here, the difference between the expansions of the two pipework systems must be taken into account. The steam main will be operating at a higher temperature than that of the condensate main, and the two connection points will move relative to each other during system warm-up.

Fig. 10.4.2 Flexibility in connection to condensate return line

The amount of movement to be taken up by the piping and any device incorporated in it can be reduced by 'cold draw'. The total amount of expansion is first calculated for each section between fixed anchor points. The pipes are left short by half of this amount, and stretched cold by pulling up bolts at a flanged joint, so that at ambient temperature, the system is stressed in one direction. When warmed through half of the total temperature rise, the piping is unstressed. At working temperature and having fully expanded, the piping is stressed in the opposite direction. The effect is that instead of being stressed from 0 F to +1 F units of force, the piping is stressed from - F to + F units of force. In practical terms, the pipework is assembled cold with a spacer piece, of length equal to half the expansion, between two flanges. When the pipework is fully installed and anchored at both ends, the spacer is removed and the joint pulled up tight (see Figure 10.4.3).

Fig. 10.4.3 Use of spacer for expansion when pipework is installed The remaining part of the expansion, if not accepted by the natural flexibility of the pipework will call for the use of an expansion fitting. In practice, pipework expansion and support can be classified into three areas as shown in Figure 10.4.4.

Fig. 10.4.4 Diagram of pipeline with fixed point, variable anchor point and expansion fitting The fixed or 'anchor' points 'A' provide a datum position from which expansion takes place.

The sliding support points 'B' allow free movement for expansion of the pipework, while keeping the pipeline in alignment. The expansion device at point 'C' is to accommodate the expansion and contraction of the pipe.

Fig. 10.4.5 Chair and roller

Fig. 10.4.6 Chair roller and saddle Roller supports (Figure 10.4.5 and 10.4.6) are ideal methods for supporting pipes, at the same time allowing them to move in two directions. For steel pipework, the rollers should be manufactured from ferrous material. For copper pipework, they should be manufactured from non-ferrous material. It is good practice for pipework supported on rollers to be fitted with a pipe saddle bolted to a support bracket at not more than distances of 6 metres to keep the pipework in alignment during any expansion and contraction. Where two pipes are to be supported one below the other, it is poor practice to carry the bottom pipe from the top pipe using a pipe clip. This will cause extra stress to be added to the top pipe whose thickness has been sized to take only the stress of its working pressure. All pipe supports should be specifically designed to suit the outside diameter of the pipe concerned. Top

Expansion fittings

The expansion fitting ('C' Figure 10.4.4) is one method of accommodating expansion. These fittings are placed within a line, and are designed to accommodate the expansion, without the total length of the line changing. They are commonly called expansion bellows, due to the bellows construction of the expansion sleeve. Other expansion fittings can be made from the pipework itself. This can be a cheaper way to solve the problem, but more space is needed to accommodate the pipe.

Full loop

This is simply one complete turn of the pipe and, on steam pipework, should preferably be fitted in a horizontal rather than a vertical position to prevent condensate accumulating on the upstream side. The downstream side passes below the upstream side and great care must be taken that it is not fitted the wrong way round, as condensate can accumulate in the bottom. When full loops are to be fitted in a confined space, care must be taken to specify that wrong-handed loops are not supplied.

The full loop does not produce a force in opposition to the expanding pipework as in some other types, but with steam pressure inside the loop, there is a slight tendency to unwind, which puts an additional stress on the flanges.

Fig. 10.4.7 Full loop This design is used rarely today due to the space taken up by the pipework, and proprietary expansion bellows are now more readily available. However large steam users such as power stations or establishments with large outside distribution systems still tend to use full loop type expansion devices, as space is usually available and the cost is relatively low.

Horseshoe

or

lyre

loop

When space is available this type is sometimes used. It is best fitted horizontally so that the loop and the main are on the same plane. Pressure does not tend to blow the ends of the loop apart, but there is a very slight straightening out effect. This is due to the design but causes no misalignment of the flanges. If any of these arrangements are fitted with the loop vertically above the pipe then a drain point must be provided on the upstream side as depicted in Figure 10.4.8.

Fig. 10.4.8 Horseshoe or lyre loop

Expansion loops

Fig. 10.4.9 Expansion loop

The expansion loop can be fabricated from lengths of straight pipes and elbows welded at the joints (Figure 10.4.9). An indication of the expansion of pipe that can be accommodated by these assemblies is shown in Figure 10.4.10. It can be seen from Figure 10.4.9 that the depth of the loop should be twice the width, and the width is determined from Figure 10.4.10, knowing the total amount of expansion expected from the pipes either side of the loop.

Fig. 10.4.10 Expansion loop capacity for carbon steel pipes

Sliding joint

These are sometimes used because they take up little room, but it is essential that the pipeline is rigidly anchored and guided in strict accordance with the manufacturers' instructions; otherwise steam pressure acting on the cross sectional area of the sleeve part of the joint tends to blow the joint apart in opposition to the forces produced by the expanding pipework (see Figure 10.4.11). Misalignment will cause the sliding sleeve to bend, while regular maintenance of the gland packing may also be needed.

Fig. 10.4.11 Sliding joint

Expansion bellows

An expansion bellows, Figures 10.4.12, has the advantage that it requires no packing (as does the sliding joint type). But it does have the same disadvantages as the sliding joint in that pressure inside tends to extend the fitting, consequently, anchors and guides must be able to withstand this force.

Fig. 10.4.12 Simple expansion bellows Bellows may incorporate limit rods, which limit over-compression and over-extension of the element. These may have little function under normal operating conditions, as most simple bellows assemblies are able to withstand small lateral and angular movement. However, in the event of anchor failure, they behave as tie rods and contain the pressure thrust forces, preventing damage to the unit whilst reducing the possibility of further damage to piping, equipment and personnel (Figure 10.4.13 (b)). Where larger forces are expected, some form of additional mechanical reinforcement should be built into the device, such as hinged stay bars (Figure 10.4.13 (c)). There is invariably more than one way to accommodate the relative movement between two laterally displaced pipes depending upon the relative positions of bellows anchors and guides. In terms of preference, axial displacement is better than angular, which in turn, is better than lateral. Angular and lateral movement should be avoided wherever possible. Figure 10.4.13 (a), (b), and (c) give a rough indication of the effects of these movements, but, under all circumstances, it is highly recommended that expert advice is sought from the bellows' manufacturer regarding any installation of expansion bellows.

Fig. 10.4.13 (a) Axial movement of bellows

Fig. 10.4.13 (b) Lateral and angular movement of bellows

Fig. 10.4.13 (c) Angular and axial movement of bellows Top

Pipe support spacing

The frequency of pipe supports will vary according to the bore of the pipe; the actual pipe material (i.e. steel or copper); and whether the pipe is horizontal or vertical. Some practical points worthy of consideration are as follows:

Pipe supports should be provided at intervals not greater than shown in Table 10.4.3, and run along those parts of buildings and structures where appropriate supports may be mounted. Where two or more pipes are supported on a common bracket, the spacing between the supports should be that for the smallest pipe. When an appreciable movement will occur, i.e. where straight pipes are greater than 15 metres in length, the supports should be of the roller type as outlined previously. Vertical pipes should be adequately supported at the base, to withstand the total weight of the vertical pipe and the fluid within it. Branches from vertical pipes must not be used as a means of support for the pipe, because this will place undue strain upon the tee joint. All pipe supports should be specifically designed to suit the outside diameter of the pipe concerned. The use of oversized pipe brackets is not good practice.

Table 10.4.3 can be used as a guide when calculating the distance between pipe supports for steel and copper pipework.

Table 10.4.3 Recommended support for pipework The subject of pipe supports is covered comprehensively in the European standard EN 13480, Part3.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Expansion Calculation and Loop Sizing001Document2 paginiExpansion Calculation and Loop Sizing001Joseph R. F. DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- Heat Exchanger Piping DesignDocument24 paginiHeat Exchanger Piping DesignManan100% (2)

- Expansion Loop DesignDocument61 paginiExpansion Loop DesignTauqueerAhmadÎncă nu există evaluări

- PlotplanDocument19 paginiPlotplanmsriref9333Încă nu există evaluări

- Column Piping Study Layout NoDocument21 paginiColumn Piping Study Layout NoTAMIZHKARTHIKÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rack Piping For A Piping Stress EngineerDocument4 paginiRack Piping For A Piping Stress EngineerFaizal Khan100% (2)

- Column Piping - Study Layout, Nozzle Orientation & Platforms RequirementsDocument23 paginiColumn Piping - Study Layout, Nozzle Orientation & Platforms Requirementsarfat nadaf100% (1)

- Distillation Column Nozzle Location Guidelines PDFDocument21 paginiDistillation Column Nozzle Location Guidelines PDFShyam MurugesanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Principles of Process Plant layout-RIL PDFDocument16 paginiPrinciples of Process Plant layout-RIL PDFPedro DiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quick Check On Piping FlexibilityDocument8 paginiQuick Check On Piping Flexibilitysateesh chandÎncă nu există evaluări

- An Article For Piping Design Guide of Reactors - What Is Piping PDFDocument19 paginiAn Article For Piping Design Guide of Reactors - What Is Piping PDFsyedahmad39Încă nu există evaluări

- Piping Design Guide-Vertical DrumsDocument9 paginiPiping Design Guide-Vertical DrumsTejas PatelÎncă nu există evaluări

- PVE Piping Layout Presentation - Part 1Document68 paginiPVE Piping Layout Presentation - Part 1Nguyen Quang NghiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piping Input and OutputDocument7 paginiPiping Input and OutputpraneshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basics of Pipe For Oil & Gas EngineerDocument12 paginiBasics of Pipe For Oil & Gas EngineerMannuddin KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Overview of GRP PipesDocument14 paginiOverview of GRP PipesMD IBRARÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Brief Description of Sway Brace, Strut and Snubber (Dynamic Restraints) For Pipe Supporting For Process IndustriesDocument7 paginiA Brief Description of Sway Brace, Strut and Snubber (Dynamic Restraints) For Pipe Supporting For Process IndustriesiaftÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piping Stress QuestionDocument9 paginiPiping Stress Questionzafarbadal100% (1)

- Chapter 12 - Pipe Ra - 2018 - The Engineer S Guide To Plant Layout and Piping deDocument21 paginiChapter 12 - Pipe Ra - 2018 - The Engineer S Guide To Plant Layout and Piping deezeabrilÎncă nu există evaluări

- 436 Piping Course DescriptionDocument2 pagini436 Piping Course DescriptionAnonymous q9eCZHMuS100% (1)

- Form A-1P Manufacturer'S Data Report For Plate Heat Exchangers As Required by The Provisions of The ASME Code Rules, Section VIII, Division 2Document2 paginiForm A-1P Manufacturer'S Data Report For Plate Heat Exchangers As Required by The Provisions of The ASME Code Rules, Section VIII, Division 2Emma DÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design Practice General PipeDocument8 paginiDesign Practice General PipedevÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2-Plant Layout - Pipeway DesignDocument25 pagini2-Plant Layout - Pipeway DesignLaxmikant SawleshwarkarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basics On Piping LayoutDocument11 paginiBasics On Piping Layoutpuru55980Încă nu există evaluări

- Supporting of Piping SystemsDocument3 paginiSupporting of Piping Systemsaap150% (2)

- Rack PipingDocument6 paginiRack PipingMayank Sethi100% (1)

- Introduction To Piping Material ActivitiesDocument23 paginiIntroduction To Piping Material Activitiesvikas2510100% (1)

- Adding 3D Pipe Supports To A Specification Using The CADWorx Specification Editor PDFDocument19 paginiAdding 3D Pipe Supports To A Specification Using The CADWorx Specification Editor PDFangel gabriel perez valdez100% (1)

- Jacketed PipesDocument11 paginiJacketed PipesvuongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jacketed Ball Valves LeafletDocument2 paginiJacketed Ball Valves LeafletSherif EltoukhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11.plant Layout PumpsDocument16 pagini11.plant Layout Pumpshalder_kalyan9216Încă nu există evaluări

- PVE Piping Layout Presentation - Part 2Document117 paginiPVE Piping Layout Presentation - Part 2Nguyen Quang NghiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piping Designers Vessel OrientationDocument13 paginiPiping Designers Vessel OrientationkazishidotaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Caesar II Load CaseDocument2 paginiCaesar II Load CasevikramacbÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation On: Internal Attachments - ABSORBERDocument14 paginiPresentation On: Internal Attachments - ABSORBERmuraliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Process Plant Layout and Piping Design: Fundamentals ofDocument4 paginiProcess Plant Layout and Piping Design: Fundamentals ofSolakhudin Al Ayubi100% (1)

- Chapter 8 Steam PipingDocument14 paginiChapter 8 Steam PipingChen WsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Secondary Pipe Support Devices: Secondary Pipe Support DevicesDocument34 paginiSecondary Pipe Support Devices: Secondary Pipe Support DeviceszebmechÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipe Stress Analysis & Design Services - Openso EngineeringDocument2 paginiPipe Stress Analysis & Design Services - Openso EngineeringAmit Sharma100% (1)

- ASME Piping Code 2007 ANSI CodeDocument162 paginiASME Piping Code 2007 ANSI CodeKhyle Laurenz DuroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piping IsometricDocument19 paginiPiping IsometricdeepakÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1722 Piping Drafting Instruc GuideDocument26 pagini1722 Piping Drafting Instruc GuideRizwan Ashraf100% (2)

- Material Selection and SpecificationDocument50 paginiMaterial Selection and SpecificationbashirÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipeline Stress Analysis With Caesar IIDocument16 paginiPipeline Stress Analysis With Caesar IIPugel YeremiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Flange Pipe SupportDocument1 paginăFlange Pipe SupportindeskeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 PipelineDocument69 pagini1 PipelineEhab MohammedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design Detailed Stress Analysis of Double Walled PipingDocument12 paginiDesign Detailed Stress Analysis of Double Walled PipingpritamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Metal Valves & Pipe Fittings World Summary: Market Values & Financials by CountryDe la EverandMetal Valves & Pipe Fittings World Summary: Market Values & Financials by CountryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipe Expansion and Support - DeterminationDocument23 paginiPipe Expansion and Support - DeterminationGodwinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipe Expansion and Support - International Site For Spirax SarcoDocument8 paginiPipe Expansion and Support - International Site For Spirax SarcoSandi ApriandiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipe Expansion and Support - International Site For Spirax SarcoDocument8 paginiPipe Expansion and Support - International Site For Spirax SarcoVenkatesh NatlaÎncă nu există evaluări

- WWW Spiraxsarco Com Resources Steam Engineering Tutorials ST 3Document12 paginiWWW Spiraxsarco Com Resources Steam Engineering Tutorials ST 3Mashudi FikriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipe Expansion and SupportDocument11 paginiPipe Expansion and SupportLorenzoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Span CalculationDocument2 paginiSpan CalculationMohit BauskarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steam-Engineering-Tutorial R1Document6 paginiSteam-Engineering-Tutorial R1Teeranai ThaiteamsingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Above Ground Pipeline DesignDocument15 paginiAbove Ground Pipeline DesigndilimgeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Parte 3.-Piping Design Carrier HandBookDocument122 paginiParte 3.-Piping Design Carrier HandBookNestor Sanchez Villasmil100% (8)

- Piping DesignDocument122 paginiPiping Designfacebookshop100% (9)

- HVAC Handbook Part 3 Piping DesignDocument122 paginiHVAC Handbook Part 3 Piping DesignTanveer100% (7)

- Piping Flexibility - Thermal Expansion in PipingDocument6 paginiPiping Flexibility - Thermal Expansion in PipingMohamed Al-OdatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Norsok L-CR-003Document41 paginiNorsok L-CR-003asoka.pwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Materials - and Impact of - : Effects Economic CorrosionDocument5 paginiMaterials - and Impact of - : Effects Economic CorrosiondasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipe DesignDocument6 paginiPipe DesignmaneeshmsanjagiriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Steam Pipeline SizingDocument25 paginiSteam Pipeline SizingniteshchouhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipe Wall Thickness CalculationDocument17 paginiPipe Wall Thickness CalculationdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calculation Pressure DropDocument9 paginiCalculation Pressure DropdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instrument Installation Hook Up DrawingsDocument0 paginiInstrument Installation Hook Up DrawingsHicoolguy Riq33% (3)

- Piping InfoDocument13 paginiPiping InfodasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 190 SpagesDocument4 pagini190 SpagesIván López Pavez100% (1)

- Piping Arrangement System PDFDocument129 paginiPiping Arrangement System PDFdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Project Standards and Specifications Layout and Spacing Rev1.0Document17 paginiProject Standards and Specifications Layout and Spacing Rev1.0Mert EfeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Approval Process Handbook 2015 16Document193 paginiApproval Process Handbook 2015 16AakashParanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piping Drawing Checking ProcedureDocument2 paginiPiping Drawing Checking Proceduredasubhai100% (1)

- Types of Fluid Flow MetersDocument10 paginiTypes of Fluid Flow MetersdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plot PlanDocument5 paginiPlot PlandasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Piping Layout: Philosophy of Yard PipingDocument11 paginiPiping Layout: Philosophy of Yard PipingdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electrical Works 2003Document15 paginiElectrical Works 2003dasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Technical 694 Cable - 1Document21 paginiTechnical 694 Cable - 1santoshcutyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plot PlanDocument5 paginiPlot PlandasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Equpment LayoutDocument6 paginiEqupment LayoutdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pipe Flow CalculatorsDocument7 paginiPipe Flow CalculatorsdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Calculations For TankDocument6 paginiCalculations For TankdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Alzheimer's Disease: Unraveling The Mystery: To Get The Most Out of This BookDocument2 paginiAlzheimer's Disease: Unraveling The Mystery: To Get The Most Out of This BookdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- P&id - 1Document5 paginiP&id - 1dasubhai100% (1)

- Fundamentals of Welding TechDocument29 paginiFundamentals of Welding TechAshwani DograÎncă nu există evaluări

- RCC Thumb RuleDocument7 paginiRCC Thumb RuleRahat ullah100% (6)

- ACI - 318 - 05 Design of Slab PDFDocument24 paginiACI - 318 - 05 Design of Slab PDFtaz_taz3Încă nu există evaluări

- Nalytical Ethod Evelopment ND Ethod Alidation F PH Ndependent Torvastatin Alcium Y - Isible Pectroscopic EthodDocument8 paginiNalytical Ethod Evelopment ND Ethod Alidation F PH Ndependent Torvastatin Alcium Y - Isible Pectroscopic EthoddasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thumb Rules For Designing A Column Layout - Civil Engineering - Civil Engineering ProjectsDocument6 paginiThumb Rules For Designing A Column Layout - Civil Engineering - Civil Engineering ProjectsThulasi Raman Kowsigan0% (1)

- Arijit IndexDocument1 paginăArijit IndexdasubhaiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Significance of The Ratio of Tensile StrengthDocument6 paginiSignificance of The Ratio of Tensile StrengthPaul Pinos-anÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hardie Plank Installation GuideDocument1 paginăHardie Plank Installation GuideBrandon VieceliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Di H2O Supply: External Calibration Gas PortDocument2 paginiDi H2O Supply: External Calibration Gas Portanwar sadatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Service Cabinet and Transformer Breaker Sizing 1082004Document49 paginiService Cabinet and Transformer Breaker Sizing 1082004Hazem HassanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dumbwaiter Installation PDFDocument20 paginiDumbwaiter Installation PDFAgnelo FernandesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dws Info Sheet Braided Well Services Strands FormedDocument1 paginăDws Info Sheet Braided Well Services Strands Formederwin atmadjaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Original Material "S" Green: Technical InformationDocument1 paginăOriginal Material "S" Green: Technical InformationPedro Henriques RamosÎncă nu există evaluări

- N4000-6 FC N4000-6 FC LD: Fast-Cure, High-Tg Multifunctional EpoxyDocument2 paginiN4000-6 FC N4000-6 FC LD: Fast-Cure, High-Tg Multifunctional EpoxyRafael CastroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ac Dur Sba G PDFDocument2 paginiAc Dur Sba G PDFbhagwatpatilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Building PlanDocument1 paginăBuilding Planshaik moizÎncă nu există evaluări

- b1 Structure 1st Edition Amendment 15Document92 paginib1 Structure 1st Edition Amendment 15marceti961Încă nu există evaluări

- Deluxe Test Probe Kit Assembly Instruction by KK4HXJ - RevisedDocument6 paginiDeluxe Test Probe Kit Assembly Instruction by KK4HXJ - ReviseddonsterthemonsterÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Aluminium Based Metal Matrix Composites Reinforced With Alumina and Sic IJERTV6IS030506Document6 paginiAnalysis of Mechanical Properties of Aluminium Based Metal Matrix Composites Reinforced With Alumina and Sic IJERTV6IS030506Gona sunil kumar reddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- DVM S Technical Bulletins - DVM S System Refrigerant Pump Down Guideline PDFDocument2 paginiDVM S Technical Bulletins - DVM S System Refrigerant Pump Down Guideline PDFDavid AlmeidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Review ArticleDocument16 paginiReview ArticleAnteneh GeremewÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ball Valve TFP600ADocument1 paginăBall Valve TFP600AGustavo J. RafaelÎncă nu există evaluări

- PCM-Based Building Envelope Systems: Benjamin DurakovićDocument201 paginiPCM-Based Building Envelope Systems: Benjamin DurakovićLam DesmondÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Guide To Fall Protection in Industry R1Document51 paginiA Guide To Fall Protection in Industry R1Nitish GunessÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fibre Reinforced Post PDFDocument2 paginiFibre Reinforced Post PDFAnneÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lubricated Plug Valves: Price List #3119 - Effective: 3/1/19Document16 paginiLubricated Plug Valves: Price List #3119 - Effective: 3/1/19nurhadiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fittings & Flanges For Pipe Series 2410 and 3410 Using The TaperTaper Adhesive-Bonded Joint FP657-10 0898Document40 paginiFittings & Flanges For Pipe Series 2410 and 3410 Using The TaperTaper Adhesive-Bonded Joint FP657-10 0898nidhinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Inspection and Test Plan For Piping (PP/FRP Piping)Document2 paginiInspection and Test Plan For Piping (PP/FRP Piping)Anonymous EyK4vt6Y100% (1)

- Steel Design 7 Nov 2020Document2 paginiSteel Design 7 Nov 2020Justine Ejay MoscosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Avalon Astoria Service Manual PDFDocument106 paginiAvalon Astoria Service Manual PDFexchangenriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nippon Company Profile-Unlocked PDFDocument30 paginiNippon Company Profile-Unlocked PDFAthul T.NÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lifting Lug Design B 01Document22 paginiLifting Lug Design B 01bakellyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Home Construction Cost Calculator - UltratechDocument7 paginiHome Construction Cost Calculator - UltratechAkshayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wan Mohammad 2017 IOP Conf. Ser.3A Mater. Sci. Eng. 271 012059 PDFDocument8 paginiWan Mohammad 2017 IOP Conf. Ser.3A Mater. Sci. Eng. 271 012059 PDFCess IshaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Avtl 104 Instructions For UseDocument72 paginiAvtl 104 Instructions For Usechirayus_3Încă nu există evaluări

- DOWSIL™ 2-9034 Emulsion: Features & BenefitsDocument5 paginiDOWSIL™ 2-9034 Emulsion: Features & BenefitsLaban KantorÎncă nu există evaluări