Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

A11-00227 King, Dawn V City, Court of Appeals, Whistleblower Lawsuit

Încărcat de

Ben BairdDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A11-00227 King, Dawn V City, Court of Appeals, Whistleblower Lawsuit

Încărcat de

Ben BairdDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

STATE OF MICHIGAN COURT OF APPEALS

DAWN KING, Plaintiff-Appellant, v CITY OF ANN ARBOR, Defendant-Appellee.

UNPUBLISHED April 12, 2012

No. 303073 Washtenaw Circuit Court LC No. 10-000751-CD

Before: FORT HOOD, P.J., and CAVANAGH and K. F. KELLY, JJ. PER CURIAM. Plaintiff, Dawn King, appeals as of right from a February 25, 2011, order entered by Washtenaw Circuit Court Judge Timothy P. Connors, which granted defendant, the City of Ann Arbor, summary disposition in plaintiffs action brought under the Michigan Whistleblower Protection Act (WPA), MCL 15.361 et seq. We affirm. I. BASIC FACTS On July 15, 2010, plaintiff filed her complaint alleging violation of the WPA. Plaintiff, a police officer with the city, claimed that she was retaliated against when she made a report to the Michigan Occupational Safety and Health Administration (MIOSHA) regarding a carbon monoxide alarm that sounded at City Hall on April 14 and April 15, 2010. Plaintiff alleged that defendant retaliated against her on May 14, 2010, when it refused to re-open her accident fund compensation case for an injury she suffered while on duty in March 2009. On March 12, 2009, plaintiff injured her shoulder during an arrest. The injury was deemed work-related and covered by workers compensation. Plaintiff was released to full duty on March 25, 2009. However, on March 31, 2009, plaintiff suffered an injury to her chest during a training exercise. Again, there was no question that the injury was work-related and covered by workers compensation. Plaintiff was released to return to full duty on April 13, 2009. Plaintiff complained of continued chest pain on September 8, 2009. She received additional treatment under workers compensation and was returned to full duty on September 19, 2009. On October 1, 2009, Kelly Beck, the Benefits Supervisor for the City of Ann Arbor, informed plaintiff that any treatment received after September 19, 2009, would not be covered under workers compensation and that plaintiffs claim could be reevaluated if she submitted additional medical documentation. -1-

The third-party administrator for the citys workers compensation claims was The Accident Fund. On October 14, 2009, The Accident Fund filed a Notice of Dispute with the Workers Compensation Agency, disputing any of plaintiffs medical claims until further review. On October 15, 2009, plaintiff requested that her workers compensation claim be reopened. After reviewing plaintiffs medical records, the Accident Fund filed a second Notice of Dispute on February 1, 2010. At Becks suggestion, the Accident Fund sent plaintiff for an independent medical examination (IME) on February 27, 2010, which confirmed that plaintiffs claims were not work-related. On May 14, 2010, plaintiff sent Beck an email, acknowledging that her case had been closed, but requesting that it be reopened in light of her physicians recent confirmation by bone scan that plaintiffs work-related injury persists. Her request was denied. Plaintiff claimed that defendants refusal to reopen her workers compensation claim was based on her MIOSHA complaint. She explained that she had been a police officer with the city for 23 years. She was also vice president of the officers union until she filed the instant lawsuit. Since 2008, plaintiff had informed management of her concerns regarding the safety of the building. Notably, some 20 former or current officers had cancer that may have been the result of exposure to radon or asbestos. When the building underwent renovation, the city agreed to safeguard employees as a result of a grievance filed by the officers union. However, plaintiff argued that the city broke the agreement and additional exposure occurred. Plaintiff filed her MIOSHA complaint on April 15, 2010, after the carbon monoxide alarm sounded. On April 1, 2010, plaintiff was examined by Dr. Marc Strickler who, for the first time, was able to provide concrete evidence of plaintiffs injury by utilizing a bone scan. Plaintiff sought to reopen her workers compensation claim, but was informed by Beck in May 2010 that the claim would not be reopened. Plaintiff filed her WPA claim on July 15, 2010. Defendant filed a motion for summary disposition on September 14, 2010, arguing that plaintiffs claim fell outside of the 90-day statute of limitations period provided by the WPA and that plaintiff failed to state a claim for which relief could be granted. Attached to the motion were the affidavits of Beck and Robert Cariano, Safety Manager for the City of Ann Arbor. Both averred that they were unaware that plaintiff had lodged a complaint with MIOSHA. On September 29, 2010, plaintiff filed handwritten responses to defendants requests for admission. Plaintiff admitted the following: 4. Admit that Plaintiff Dawn King was released to full duty with no restrictions on September 19, 2009, by Concentra. 5. Admit that a Notice of Dispute on Plaintiff Dawn Kings workers disability compensation claim was filed on or about October 14, 2009. 6. Admit that Plaintiff Dawn King did not file a formal application for hearing on mediation with the Workers Compensation Agency following the October 14, 2009 Notice of Dispute. 7. Admit that a Notice of Dispute on Plaintiff Dawn Kings workers disability compensation claim was filed on or about February 1, 2010. -2-

8. Admit that Plaintiff Dawn King did not file a formal application for hearing on mediation with the Workers Compensation Agency following the February 1, 2010 Notice of Dispute. *** 10. Admit that Plaintiff Dawn King did not inform the Citys Safety Director, Bob Cariano, that she had reported the April 14th or April 15th carbon monoxide incident to MIOSHA. 11. Admit that Plaintiff Dawn King did not inform the Citys Benefit Manager Kelly Beck that she had reported the April 14th or April 15th carbon monoxide incident to MIOSHA. 12. Admit that Accident Fund is the Citys third party administrator for workers disability compensation claims. 13. Admit that Plaintiff Dawn King did not inform any personnel from the Accident Fund that she had reported the April 14th or April 15th carbon monoxide incident to MIOSHA. As a result of these admissions, defendant filed an amendment to its motion for summary disposition on October 18, 2010. Defendant argued that plaintiff defeated her own claim by admitting that none of the decision-makers were informed of her MIOSHA report. The trial court agreed: [I]ts just clear on its face to me the admissions to the request for admissions number 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, and 13, those requests were very specific. The admissions . . . standing on their own, as you said, sir, would defeat the Plaintiffs Complaint; that she admits the city had disputed her workers compensation claim for months prior to the April MIOSHA report. She admits she never told Kelly Beck or the [A]ccident [F]und about her MIOSHA report. She admits she didnt even tell the safety director, Bob Cariano, about her report. She cant demonstrate a proper connection between the April report and the May reinstatement of the citys prior position on her workmans compensation claim. She has no evidence to support that the decision maker even had any knowledge of her report, and under the law that on its face indicates that she cant she cant even get to a jury on that. The trial court entered an order granting defendant summary disposition and plaintiff now appeals as of right. II. ANALYSIS Whether a plaintiff has established a prima facie case under the WPA is a question of law subject to de novo review. Manzo v Petrella, 261 Mich App 705, 711; 683 NW2d 699 (2004). We also review de novo a trial courts decision on a motion for summary disposition. Odom v Wayne Co, 482 Mich 459, 466; 760 NW2d 217 (2008). Summary disposition is appropriate -3-

under MCR 2.116(C)(10) when there is no genuine issue of material fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. MCR 2.116(C)(10); Lanigan v Huron Valley Hosp, Inc, 282 Mich App 558, 563; 766 NW2d 896 (2009). The trial court must consider all evidence submitted by the parties in a light most favorable to the non-moving party. Lanigan, 282 Mich App at 563. A trial court must deny the motion if, after reviewing the evidence, reasonable minds might differ as to any material fact. Id. MCL 15.362 provides: An employer shall not discharge, threaten, or otherwise discriminate against an employee regarding the employees compensation, terms, conditions, location, or privileges of employment because the employee, or a person acting on behalf of the employee, reports or is about to report, verbally or in writing, a violation or a suspected violation of a law or regulation or rule promulgated pursuant to law of this state, a political subdivision of this state, or the United States to a public body, unless the employee knows that the report is false, or because an employee is requested by a public body to participate in an investigation, hearing, or inquiry held by that public body, or a court action. The underlying purpose of the WPA is protection of the public. Dolan v Continental Airlines/Continental Express, 454 Mich 373, 378; 563 NW2d 23 (1997). The WPA meets this objective by protecting the whistleblowing employee and by removing barriers that may interdict employee efforts to report violations or suspected violations of the law. Id. It is a remedial statute, and must be liberally construed to favor the persons that the Legislature intended to benefit. Chandler v Dowell Schlumberger, Inc, 456 Mich 395, 406; 572 NW2d 210 (1998). The WPA is aimed at alleviating the inability to combat corruption or criminally irresponsible behavior in the conduct of government or large businesses, by encouraging employees, who are the group best positioned to report violations of the law, to report violations by reducing their fear of retribution through prohibiting future employer reprisals against whistle blowing employees. Shallal v Catholic Social Servs of Wayne Co, 455 Mich 604, 612; 566 NW2d 571 (1997), quoting Dudewicz v Norris-Schmid, Inc, 443 Mich 68, 75; 503 NW2d 645 (1993), overruled in part on other grounds Brown v Detroit Mayor, 478 Mich 589; 734 NW2d 514 (2007). Therefore, the primary motivation of an employee pursuing a whistleblower claim must be a desire to inform the public on matters of public concern. Shallal, 455 Mich at 621. As a preliminary matter, we reject defendants claim that plaintiffs complaint was not timely filed. A person who alleges a violation of this act may bring a civil action for appropriate injunctive relief, or actual damages, or both within 90 days after the occurrence of the alleged violation of this act. MCL 15.363(1). The alleged violation of the WPA occurred on May 14, 2010, when defendant (again) denied plaintiffs request to reopen plaintiffs workers compensation claim. Plaintiff argued that this was in retaliation for her April 14 and 15, 2010, MIOSHA complaint. Plaintiff filed her complaint on July 15, 2010, within the 90-day period. Defendants contention that the limitations period was triggered in October 2009 is not well-received. The WPA could not be violated until the employer took adverse action against the employee after the employee engaged in a protected activity. The protected activity did not occur in this case until April 2010 and the alleged adverse employment action (refusal to reopen plaintiffs workers compensation claim) occurred in May 2010. -4-

In order to set forth a prima facie case under the WPA, plaintiff has to show that: 1) she was engaged in a protected activity; 2) she suffered an adverse employment action; and, 3) there was a causal connection between the protected activity and the adverse employment action. West v Gen Motors Corp, 469 Mich 177, 183184; 665 NW2d 468 (2003). The trial court and defendant concede that plaintiff was engaged in a protected activity when she filed her MIOSHA report; however, the trial court stated that plaintiff failed to meet the third prong of this three-part test. We agree that there was no causal connection between plaintiffs MIOSHA report and the decision to decline to reopen plaintiffs workers compensation claim. However, we also note that plaintiff failed to demonstrate that she suffered an adverse employment action. Adverse employment action is defined as an employment decision that is materially adverse in that it is more than a mere inconvenience or an alteration of job responsibilities; rather, there must be some objective basis for demonstrating that the change is adverse because a plaintiffs subjective impressions . . . are not controlling. Pena v Ingham Co Rd Comm, 255 Mich App 299, 311, 660 NW2d 351 (2003), quoting Wilcoxon v Minnesota Mining & Mfg Co, 235 Mich App 347, 364; 597 NW2d 250 (1999). Nevertheless, there are typical adverse employment actions, including termination, a demotion evidenced by a decrease in wage or salary, a less distinguished title, a material loss of benefits, significantly diminished material responsibilities, or other indices that might be unique to a particular situation. Pena, 255 Mich App at 312, quoting White v Burlington N & SF R Co, 310 F3d 443, 450 (CA 6, 2002). In determining the existence of an adverse employment action, courts must keep in mind the fact that [w]ork places are rarely idyllic retreats, and the mere fact that an employee is displeased by an employers act or omission does not elevate that act or omission to the level of a materially adverse employment action. Pena, 255 Mich App at 312, quoting Blackie v Maine, 75 F 3d 716, 725 (CA1, 1996). Taking the evidence in a light most favorable to plaintiff, plaintiff did not suffer an adverse employment action. Defendant took no action against plaintiff. No term or condition of plaintiffs employment was affected by defendants refusal to stand by its earlier decision not to reopen plaintiffs workers compensation claim. Plaintiff could have availed herself of the appeals process, but failed to do so. She simply did not suffer any tangible adverse employment action. Even if the denial to reopen plaintiffs workers compensation claim could be considered an adverse employment action, there is no evidence that the action was motivated by plaintiffs protected activity. Summary disposition for the defendant is appropriate when a plaintiff cannot factually demonstrate a causal link between the protected activity and the adverse employment action. West, 469 Mich at 184. If there is no evidence that the decision-maker had knowledge of the protected activity at the time of the adverse employment action, dismissal is appropriate. Kaufman & Payton, PC v Nikkila, 200 Mich App 250, 257258; 503 NW2d 728 (1993). A plaintiff may establish a causal connection through either direct evidence or indirect and circumstantial evidence. Sniecinski v. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Mich, 469 Mich 124, 132; 666 NW2d 186 (2003). Direct evidence is that which, if believed, requires the conclusion that the plaintiffs protected activity was at least a motivating factor in the employers actions. To establish causation using circumstantial evidence, the circumstantial -5-

proof must facilitate reasonable inferences of causation, not mere speculation. Speculation or mere conjecture is simply an explanation consistent with known facts or conditions, but not deducible from them as a reasonable inference. In other words, the evidence presented will be sufficient to create a triable issue of fact if the jury could reasonably infer from the evidence that the employers actions were motivated by retaliation. [Shaw v City of Ecorse, 283 Mich App 1, 14-15; 770 NW2d 31 (2009), reh den 488 Mich 852 (2010) (quotations and citations omitted).] Plaintiff failed to establish a genuine issue of material fact as to whether her MIOSHA report motivated the denial to reopen her workers compensation claim. The Accident Fund filed a Notice of Dispute with the Workers Compensation Agency on October 14, 2009. On October 15, 2009, plaintiff requested that her workers compensation claim be reopened. After reviewing plaintiffs medical records, The Accident Fund filed a second Notice of Dispute on February 1, 2010. At Becks suggestion, The Accident Fund sent plaintiff for an IME on February 27, 2010, which confirmed that plaintiffs claims were not work-related. If anything, Beck appeared to support plaintiff by requesting that the Accident Fund provide an IME. Beck had no knowledge regarding plaintiffs MIOSHA complaint when she informed plaintiff in May 2010 that her workers compensation claim would not be reopened. Plaintiff complains that Cariano knew that she was the one that made the MIOSHA report. Even assuming that to be the case, plaintiff does nothing more than speculate that Cariano had some influence over the decision to not reopen her workers compensation case. Plaintiff failed to prove that she suffered an adverse employment action or that the alleged adverse employment action was causally connected to the protected activity. Therefore, the trial court properly granted defendant summary disposition. Affirmed. As the prevailing party, defendant may tax costs. MCR 7.219. /s/ Karen M. Fort Hood /s/ Mark J. Cavanagh /s/ Kirsten Frank Kelly

-6-

S-ar putea să vă placă și

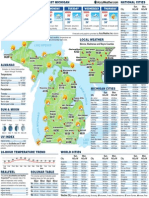

- Five-Day Weather ForecastDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ForecastBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fire Emblem Fates Hoshidan Class ChartDocument1 paginăFire Emblem Fates Hoshidan Class ChartBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five-Day Weather ForecastDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ForecastBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fire Emblem Fates Nohrian Class ChartDocument1 paginăFire Emblem Fates Nohrian Class ChartBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five-Day Weather ForecastDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ForecastBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Open Letter From Mayor John B. O'ReillyDocument1 paginăOpen Letter From Mayor John B. O'ReillyBeth DalbeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five-Day Weather ForecastDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ForecastBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five-Day Weather ForecastDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ForecastBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five-Day Weather ForecastDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ForecastBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Paul DeWolf Homicide Investigation Reward PosterDocument1 paginăPaul DeWolf Homicide Investigation Reward PosterBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five-Day Weather ForecastDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ForecastBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five-Day Weather ForecastDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ForecastErica McClainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Five-Day Weather ReportDocument1 paginăFive-Day Weather ReportBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- First Fridays Ypsilanti May 1 MapDocument1 paginăFirst Fridays Ypsilanti May 1 MapBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Washtenaw Alliance For Children and Youth 2014 Report Card Info GraphicsDocument2 paginiWashtenaw Alliance For Children and Youth 2014 Report Card Info GraphicsBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Saline 2013 Police Golf Outing BrochureDocument2 paginiSaline 2013 Police Golf Outing BrochureBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Washtenaw County Hall of Honor Biographies of Fallen DeputiesDocument4 paginiWashtenaw County Hall of Honor Biographies of Fallen DeputiesBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- HDC, LLC v. City - OpinionDocument10 paginiHDC, LLC v. City - OpinionBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Map of Percentage of Taxable Value Is From PPT by County in MichiganDocument1 paginăMap of Percentage of Taxable Value Is From PPT by County in MichiganBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Opinion and Order To Dismiss VR Entertainment vs. Ann ArborDocument13 paginiOpinion and Order To Dismiss VR Entertainment vs. Ann ArborBen BairdÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fireworks Law PDFDocument2 paginiFireworks Law PDFTyler ColinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Jurisdiction in Estafa CaseDocument1 paginăJurisdiction in Estafa CaseReymart-Vin MagulianoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hortizuela vs. Tagufa - Reversion-ReconveyanceDocument8 paginiHortizuela vs. Tagufa - Reversion-ReconveyanceNazi Jester U. ErfeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mahinay Vs Gako Case DigestDocument3 paginiMahinay Vs Gako Case DigestLou100% (1)

- People V SolarDocument2 paginiPeople V SolarMaria Dariz AlbiolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Act of State DoctrineDocument5 paginiAct of State DoctrinerethiramÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bryant v. Washington Mutual Bank ruling on motion to dismissDocument19 paginiBryant v. Washington Mutual Bank ruling on motion to dismissMarques YoungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hugo E. Ribadeneira, Cross-Appellee v. Director of Taxation, Department of Revenue, State of Kansas, 161 F.3d 18, 10th Cir. (1998)Document3 paginiHugo E. Ribadeneira, Cross-Appellee v. Director of Taxation, Department of Revenue, State of Kansas, 161 F.3d 18, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balance of ConvenienceDocument5 paginiBalance of ConvenienceZiyad Rv100% (2)

- Attorneys For Plaintiff Oracle America, IncDocument20 paginiAttorneys For Plaintiff Oracle America, Incsabatino123Încă nu există evaluări

- Jose Antonio Leviste V CADocument1 paginăJose Antonio Leviste V CAAbby PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rule 65: Certiorari, Prohibition and Mandamus: Errors of JurisdictionDocument34 paginiRule 65: Certiorari, Prohibition and Mandamus: Errors of JurisdictionRapRalph GalagalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- United States v. Lynn Duane Hewitt, 89 F.3d 830, 4th Cir. (1996)Document3 paginiUnited States v. Lynn Duane Hewitt, 89 F.3d 830, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Case No. 583) : Prepared By: Cecille Diane DJ. MangaserDocument1 pagină(Case No. 583) : Prepared By: Cecille Diane DJ. MangaserCecille MangaserÎncă nu există evaluări

- Widow and Children of Slain Employee Seek Damages from Employers in Regular CourtDocument3 paginiWidow and Children of Slain Employee Seek Damages from Employers in Regular Courtchappy_leigh118Încă nu există evaluări

- The State of Bombay Vs Purushottam Jog Naik 260519s520016COM471676Document5 paginiThe State of Bombay Vs Purushottam Jog Naik 260519s520016COM471676Utkarsh KhandelwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- People v. Gorospe: Discretion To Limit The Cross Examination and To Consider It Terminated Donated IfDocument2 paginiPeople v. Gorospe: Discretion To Limit The Cross Examination and To Consider It Terminated Donated IfTootsie GuzmaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abilene Motion To Expunge 2Document5 paginiAbilene Motion To Expunge 2MonzkyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wigberto Tanada Vs ComElecDocument10 paginiWigberto Tanada Vs ComElecJohnday MartirezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Yared Vs Tiongco 659 SCRA 545Document2 paginiYared Vs Tiongco 659 SCRA 545Achilles Neil EbronÎncă nu există evaluări

- Del Socorro vs. Van WilsemDocument3 paginiDel Socorro vs. Van WilsemMikkoy1880% (5)

- Facts 1Document2 paginiFacts 1Monalizts D.Încă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 140179 March 13, 2000 ROQUE FERMO, Petitioner, vs. Commission On Elections and Manuel D. Laxina SR., RespondentsDocument68 paginiG.R. No. 140179 March 13, 2000 ROQUE FERMO, Petitioner, vs. Commission On Elections and Manuel D. Laxina SR., RespondentsNicole Ann Delos ReyesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ladlad vs. VelascoDocument12 paginiLadlad vs. Velascod.mariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Traders Royal Bank v. IACDocument6 paginiTraders Royal Bank v. IACDexter Jonas M. LumanglasÎncă nu există evaluări

- (CPR) Gequilasao v. FortalezaDocument7 pagini(CPR) Gequilasao v. FortalezaChristian Edward CoronadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs CA G.R. No. 140285Document2 paginiPeople Vs CA G.R. No. 140285CJ FaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nicanor Gatmaytan JR., vs. Atty. Isidro Ilao (A.C. NO. 6086: January 26, 2005)Document5 paginiNicanor Gatmaytan JR., vs. Atty. Isidro Ilao (A.C. NO. 6086: January 26, 2005)KathÎncă nu există evaluări

- Crim Procedures Questions and AnswersDocument28 paginiCrim Procedures Questions and AnswersCrisostomo Lito91% (11)

- Anthony Tamilio v. Walter Fogg, Superintendent, Eastern Correctional Facility, and Robert Abrams, Attorney General of New York, 713 F.2d 18, 2d Cir. (1983)Document5 paginiAnthony Tamilio v. Walter Fogg, Superintendent, Eastern Correctional Facility, and Robert Abrams, Attorney General of New York, 713 F.2d 18, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Remedial Law - CRIM PRO (Pros. Centeno)Document61 paginiRemedial Law - CRIM PRO (Pros. Centeno)Eisley Sarzadilla-GarciaÎncă nu există evaluări