Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Contemporary Adaptation: Costume Comparisons

Încărcat de

Mary LangridgeTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Contemporary Adaptation: Costume Comparisons

Încărcat de

Mary LangridgeDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

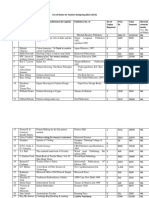

Mary Langridge Professor Avila DES 143 23 January 2012 Contemporary Adaptation #1: The Ancient Middle East

(fig. 1) Faience Bead-net dress from Giza Egyptian, Old Kingdom, 2551-2528 B.C. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

(fig. 2) Marios Schwab Swarovski Crystal Net overlay dress, Spring 2012 RTW Elle Magazine

Ancient Egyptian Bead-net Dress The bead-net dress in fig. 1 is from the Old Kingdom dating from 25512528 B.C. It features a pectoral neckpiece that functions as a collar and a triangle top that is banded under the breasts to connect a form-fitting fringed skirt. Bead-nets were made of faience, a brightly colored glazed powdered quartz (Lucas 155). The beads construct a pattern with diamond shaped spaces. The main purpose of the bead-net dress is unknown so it must be inferred. There is debate to whether the bead-net dress was ornamental or erotic. The garment rattled with movement. Prostitutes and dancers depicted in the Turin Erotic Papyrus wore hip slung shell girdles that also rattled with movement (Hall 64). In contrast, bead-net dresses represented in statuary and relief images are worn over linen sheath dresses to simulate patterned fabric. The bead-net dress would not have been an everyday garment. Only wealthy people who did not work would be able to wear such a heavy and fragile garment. Marios Schwabs Swarovski crystal net overlay dress pictured in fig. 2 is a modern take on the ancient Egyptian bead-net dress. The triangle lines on the breasts, the belted waist, rounded neck opening, and form-fitting silhouette mimic the lines in the bead-net dress. Instead of colorful faience beads, black and clear Swarovski crystals adorn this edgy dress. The same diamond pattern is used throughout both. Instead of fringe the bottom is severely chopped to reveal a raw edge. In our society this garment would be considered risqu if worn as is. There is a sheer layer of flesh-toned mesh fabric that exposes the chest and under garments. Most people do not have any use for a delicate see-through garment so Schwabs dress would be considered a status symbol in the same way that the expertly detailed Egyptian bead-net dress would have been.

Contemporary Adaptation #2: Greek/Roman

(fig.1) Statue of a Muse, Roman copy of Greek original, 130 CE Glyptothek Museum (Munich, Germany)

(fig. 2) Marchesha one-shouldered silk gown with beaded trim, Resort 2012 Elle Magazine

Greek Himation/Roman Palla The Romans borrowed many clothing styles from the Greeks. For example, the Roman Palla is an adaptation of the Greek Himation. This multi-use mantle style shawl was usually draped over a tunica style garment. It could be worn pulled over oneshoulder or worn over the head like a veil. Fig. 1 is a Roman copy of a Greek muse statue. In this statue the palla is worn over one shoulder, similar in style to the toga. The Roman palla was a very common, versatile, and simple garment. Wool was the most universal textile used for pallas but the quality of wool varied. Women of status would be able to afford finer and softer wool. Other than wool they could be made out of linen, cotton, or silk (fashion encyclopedia). It is impossible to determine what fabric the artist was trying to convey in the statue but one can only assume that it was a fine luxurious fabric reserved for a mythical muse. The Marchesa silk gown pictured in fig. 2 is very reminiscent of the Roman palla. It is worn over one shoulder in a similar way to the draped palla. One of the main differences in modern interpretations of the palla would be that there is no tunica or stola underneath. Both the palla in fig. 1 and the gown in fig. 2 are draped with the same semicircular, high-low hem towards the bottom. Fig. 2 is more tailored than fig. 1 because it is meant to be worn as a gown instead of just a shawl. Although not evident in fig 1, the beaded stripes that outline the dress seem to be borrowed from Roman clavi trim that adorned some mens garments. In contrast, to the everyday palla that was worn by all classes this Marchesa gown would not be available to many people. The Marchesa dress would be impractical for everyday wear and would be considered a status symbol.

Contemporary Adaptation #3: Middle Ages

(fig. 1) Purple Kirtle with Green Cotehardie Romance of Alexander, 14th Century Bodleian Library

(fig. 2) Valentino Haute Couture, Long-sleeved Black Velvet Inlay Gown, Fall 2011 Elle Magazine

Middle Ages Cote-hardie and Kirtle Gown Womens kirtle gowns would have been worn close to the body . . . through the torso and flaring out to a full skirt below (Tortora 155). The purple gown in fig. 1 features tight-fitting long sleeves with a button detail. The Gown is the least visible while the cote-hardie is the most noticeable of the two. The green cote-hardie pictured is shortsleeved so you can see the purple gown peeking out at the sleeves and near the hemline. Fabric was expensive so one of the reasons for having visible under layers would be to show off wealth. Another indicator of wealth would be a very long dress to show that you did not need to work. The woman depicted in this illustration seems to have a long gown so I would assume that she is moderately wealthy but not royal because her garment is not highly adorned. The Valentino Haute Couture gown pictured in fig. 2 is similar in line and style to the 14th century cote-hardie and gown. The silhouette of the Valentino dress is long sleeved fitted trough the top half and full skirted towards the bottom. The fabric is a rich black velvet with and inset design detail. There is braiding on the neckline, sleeves, and at the waist. Although, the modern adaptation is one piece instead of two, the button detail on the sleeve mimics the button detail on the sleeve of fig.1 (as one can see in the detail image below the main picture). The higher neckline, color, and fabric detail are the only differences in style to the 14th century dress. Because of the rich fabric, attention to detail and well-known designer I would assume that this dress is very expensive and exclusive. There are not many places a woman could wear this type of haute couture gown so the average woman would not be able to wear it.

Contemporary Adaptation #4: 16th Century

(fig. 1) Queen Elizabeth I, 1580-1585, Marcus Gheeraerts Younger Private Collection

(fig. 2) Sarah Angold Laser Cut Necklace, Winter 2011 Collection F1235.com

Elizabethan Ruff Collar In fig. 1 Queen Elizabeth I in wearing a stiff ruff collar with pleated rows of fabric. The ruff was a large pleated collar that was stiffened with starch and worn around the neck to make the wearer appear as if they were holding their head up high. It originated as small ruffled collar worn by men but as popularity for them grew they increased in size. Queen Elizabeth I is wearing a closed ruff so it must have been uncomfortable and restricted movement. Ruffs varied in size over their popularity and sometimes grew to ridiculous scales. Queen Elizabeth probably liked to wear ruffs to give off the a more regal posture and powerful look. She even went so far as to pass sumptuary laws limiting the size of ruffs for people outside her court to keep their exclusivity (fashion encyclopedia). The neckpiece in fig. 2 by Sarah Angold is the modern equivalent to a ruff. It is made from laser cut acrylic and held together with magnetic fastenings. The rows of translucent acrylic can be manipulated into several configurations. These rows are much like the pleated rows in the ruff worn by Queen Elizabeth I. The size and shape are also similar. It would be impractical to wear a neckpiece like this on a daily basis but it would definitely make a statement and get the wearer noticed. It gives the wearer the same regal quality as the 16th century ruff collar. The process to make one of these neckpieces seems very labor intensive so they are expensive. I dont see collars like this Sarah Angold neckpiece becoming all the rage in modern times because it would be uncomfortable, costly and frivolous. There are differences in material between the ruff and modern acrylic neckpiece but overall they give off the same effect of power and money.

Contempary Adaptation #5: 17th Century

(fig. 1) Falling Band, Captaine Smart of the London Traynde Bandes, 1639

(fig. 2) Asos Beaded Capelet, Winter 2012

17th Century Falling Band The popularity of the ruff dwindled and people started wearing more relaxed fashions. Neck bands were a more realistic alternative to neck adornment. There were standing neck bands and falling neck bands like the one pictured in fig. 1. These bands were worn primarily by men. They could be attached at the collar with a tie fastening. Falling bands were made of silk or linen. In fig. 1 the lace edged falling band is shown resting on the shoulders. Falling bands were meant to lay flat and were highly ornamented with lace or cutouts. The lace falling band that Captaine Smart is wearing shows his status because the lace and craftsmanship that went into making the collar were expensive. The Asos beaded capelet in fig. 2 is made of sheer fabric and is beaded with a decorative edge. It appears to be ornamental in purpose similar to the falling band worn by Captaine Smart. The scalloped edges are also reminiscent of the lace edges in fig. 1. Falling bands were not normally beaded but this unique detail adds a feminine element. A capelet is made to sit flat on the shoulders in the same way as the falling band. The construction of the Asos capelet is not as complex as the falling band in fig. 1 so most people could afford this accessory. The fabric is not precious like the laces used for 17th century falling bands. This is a good example of a mass produced item of clothing with a historic influence.

Works Cited Asos Beaded Capelet Photograph. Asos. Web. 5 Feb. 2012 < http://us.asos.com/ASOS/ASOS-Beaded-Caplet/Prod/pgeproduct.> Bead-net Dress. Photograph. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Web. 21 Jan. 2012. <http://mfa.org/collections/object/beadnet-dress-146531> Hall, Rosalind M. Egyptian Textiles. Aylesbury, Bucks, UK: Shire Publications, 2008. Print. Falling Band Photograph. Web. 5 Feb. 2012 < http://the1642goodwyfe.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/captain-smart-va.jpg Fashion Encyclopedia. Website. 11 Feb. 2012. <http://www.fashionencyclopedia.com/fashion_costume_culture/The-AncientWorld-Rome/Palla.html> Lucas, A., and J. R. Harris. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries. London: E. Arnold, 1962. Print. Queen Elizabeth I Photograph. 10 Feb. 2012. <http://www.scholarsresource.com/browse/work/2144608044> Romance of Alexander Photograph. 11 Feb 2012. <http://thefashionhistorian.blogspot.com/2011/03/head-to-toe-14th-centurywoman.html> Sarah Angold photograph. 12 Feb. 2012.< http://f1235.com/products/165-sarahangold-jewellery-laser-cut-necklace-f1235-stylebox.aspx> The Fashion Historian. Website. 7 Feb. 2012 <http://thefashionhistorian.blogspot.com>

Tortora, Phyllis G., and Keith Eubank. "The Ancient Middle East." A Survey of Historic Costume. New York: Fairchild Publications, 2010. Print. Valentino Gown Photograph. Elle Magazine. Web. 6 Feb. 2012. < http://www.elle.com/Runway/Haute-Couture/Fall-2011 Couture/VALENTINO/VALENTINO > Volta, Matteo. Marios Schwab Swarovski Crystal Net Overlay Dress. Photograph. Elle Magazine. Web. 21 Jan. 2012. <http://www.elle.com/Runway/Ready-toWear/Spring-2012-RTW/MARIOS-SCHWAB/MARIOS-SCHWAB>.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Dress Design: An Account of Costume for Artists & DressmakersDe la EverandDress Design: An Account of Costume for Artists & DressmakersÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation 1Document10 paginiPresentation 1estiakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sustainability in FashionDocument79 paginiSustainability in FashionAnitha AnithaÎncă nu există evaluări

- How Clothing Represents Culture, Social Identities and StatusDocument15 paginiHow Clothing Represents Culture, Social Identities and StatusRosy KaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment On: Submitted To: Submitted byDocument6 paginiAssignment On: Submitted To: Submitted bypromitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fashion Designers DetailsDocument2 paginiFashion Designers Detailsinduj22damodarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Newsletter Vol.1Issue 3Document26 paginiNewsletter Vol.1Issue 3FashionSocietyCPP100% (1)

- Ancient Greek CostumeDocument2 paginiAncient Greek Costumelisamarie_evansÎncă nu există evaluări

- NVC in Fashion DesignDocument131 paginiNVC in Fashion DesignVera Wosu - ObiechefuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fashion Types, Trends and Current StylesDocument37 paginiFashion Types, Trends and Current Styleseroku100% (1)

- 02 - Flat SketchingDocument17 pagini02 - Flat Sketchingmaya_muth100% (2)

- Jackets in 21st Century MenswearDocument6 paginiJackets in 21st Century MenswearTarveen KaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Costume Planning Guide for Theatre ProductionsDocument5 paginiCostume Planning Guide for Theatre ProductionsAllan Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fashion in Motion Kansai YamamotoDocument2 paginiFashion in Motion Kansai Yamamotostipsa592Încă nu există evaluări

- Fashion Technology: Technical DescriptionDocument25 paginiFashion Technology: Technical DescriptionBrajbhan ShankarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clothes and Costumes of Europe in 14th and 15th CenturyDocument4 paginiClothes and Costumes of Europe in 14th and 15th Centuryanon_546047152Încă nu există evaluări

- Plastic Dreams 10 Englsih Version PDFDocument48 paginiPlastic Dreams 10 Englsih Version PDFJoaoDSilvaÎncă nu există evaluări

- B - SC - Fashion Design Batch 2018 SYLLABUSDocument101 paginiB - SC - Fashion Design Batch 2018 SYLLABUSManpreet kaur gill100% (2)

- 9 - Fashion Design & Garment Technology PDFDocument23 pagini9 - Fashion Design & Garment Technology PDFgoel0% (1)

- Fashion Cycle StepsDocument2 paginiFashion Cycle Stepssaranya narenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Art of Fashion Draping Techniques & Tools ExplainedDocument3 paginiArt of Fashion Draping Techniques & Tools ExplainednovertaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The House of Worth Part 2, The NationalDocument1 paginăThe House of Worth Part 2, The NationalLottie JohanssonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aesthetics Comparison Indian and Japanese SensibilitiesDocument20 paginiAesthetics Comparison Indian and Japanese SensibilitiesTarveen KaurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Color in Fashion: Christine Ho Mr. Schurtz English AP 12 Period 3 10 May 2010Document71 paginiColor in Fashion: Christine Ho Mr. Schurtz English AP 12 Period 3 10 May 2010christinequeho0% (1)

- History of FashionDocument23 paginiHistory of FashionRohit SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fashion Design Drawing 12Document9 paginiFashion Design Drawing 12Ioan-ovidiu CordisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Creativity in Fashion & Digital CultureDocument33 paginiCreativity in Fashion & Digital CultureAnthony100% (2)

- Chapter 4 Fashion CentersDocument48 paginiChapter 4 Fashion CentersJaswant Singh100% (1)

- Ancient Greek Clothes, Jewelry, Cosmetics and HairstylesDocument19 paginiAncient Greek Clothes, Jewelry, Cosmetics and Hairstylestoza vitaminozaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fashion Bird 2Document24 paginiFashion Bird 2Fashion BirdÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Be A Fashion RevolutionaryDocument23 paginiHow To Be A Fashion RevolutionaryTudor RadacineanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leading Lines Optical IllusionsDocument8 paginiLeading Lines Optical IllusionsJustin MagnanaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- S1o3fashionhistory 1960topresent 1Document59 paginiS1o3fashionhistory 1960topresent 1api-354317566Încă nu există evaluări

- Revised Syllabus Pattern CuttingDocument10 paginiRevised Syllabus Pattern Cuttingselwyn999100% (1)

- Egyptian Clothing: From Pharaohs to CommonersDocument6 paginiEgyptian Clothing: From Pharaohs to CommonersVivék Gaharwar OdétÎncă nu există evaluări

- History of Indian FashionDocument1 paginăHistory of Indian FashionMallikarjun RaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- List of Books Fashion DesigningDocument6 paginiList of Books Fashion DesigningShravan Kemtur100% (1)

- Market LevelsDocument14 paginiMarket LevelsvijaydhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Barathiar Univ Fashion SyllabusDocument12 paginiBarathiar Univ Fashion SyllabusShruti PanditÎncă nu există evaluări

- CCCCCCCCC CCCCCCCCCCCC C C C CDocument22 paginiCCCCCCCCC CCCCCCCCCCCC C C C CUsman ZulfiqarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fashion Design Technology CTSDocument13 paginiFashion Design Technology CTSiqbal1439988Încă nu există evaluări

- Etymology, Terminology & StyleDocument57 paginiEtymology, Terminology & StyleSushant BarnwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Trends Trade Fairs ForcastingDocument20 paginiTrends Trade Fairs ForcastingMunu SagolsemÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imagination is your passport to a whole new worldDocument20 paginiImagination is your passport to a whole new worldpriyankaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fashion Forecast WomenDocument22 paginiThe Fashion Forecast WomenAnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draping TheoryDocument20 paginiDraping TheorymohuajishnuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fashion terminology and designers explainedDocument20 paginiFashion terminology and designers explainedSanthosh KumarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Design & Fashion - June2018Document13 paginiDesign & Fashion - June2018ArtdataÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sonali PortfolioDocument31 paginiSonali PortfolioSonali RankaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assembly Guide Form I ToDocument10 paginiAssembly Guide Form I ToChivalrous SpringÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fabric For Fashion - The Complete Guide - Natural and Man-Made - Laurence King Publishing. Baum, Myka Hallett, - 2014 - Laurence King Publishing - 9781780673349 - ADocument574 paginiFabric For Fashion - The Complete Guide - Natural and Man-Made - Laurence King Publishing. Baum, Myka Hallett, - 2014 - Laurence King Publishing - 9781780673349 - AE A100% (1)

- Skirt Product ChooseDocument355 paginiSkirt Product ChooseasadnilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Salvage & Selvage: A Redesign Challenge Spotlights Fabric EdgesDocument8 paginiSalvage & Selvage: A Redesign Challenge Spotlights Fabric EdgesamelieÎncă nu există evaluări

- London - Fashion CapitalDocument34 paginiLondon - Fashion CapitalAbhishek RajÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jeans: Product Project Report OnDocument76 paginiJeans: Product Project Report Onhiren9090Încă nu există evaluări

- Garments Design and StylesDocument16 paginiGarments Design and StylesjoyceÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fashion Draping: Fashion Draping Kavitha Rajan Lecturer in Textile Technology, Ethiopian Technical University Addis AbabaDocument15 paginiFashion Draping: Fashion Draping Kavitha Rajan Lecturer in Textile Technology, Ethiopian Technical University Addis AbabakavineshpraneetaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Master Garment Production TechniquesDocument10 paginiMaster Garment Production TechniquesrichardkwofieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rolex Data Sheet PDFDocument2 paginiRolex Data Sheet PDFfahmi1987Încă nu există evaluări

- Max Fajardo Simplified Construction Estimate PDFDocument5 paginiMax Fajardo Simplified Construction Estimate PDFkanji yamashitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Santos Travel Master 2.6: Bike TestDocument3 paginiSantos Travel Master 2.6: Bike TestCiprian SorinÎncă nu există evaluări

- The 13 Best French Textbooks For French Learners of Any LevelDocument8 paginiThe 13 Best French Textbooks For French Learners of Any LeveltomsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Most Influential Living Artists of 2016Document23 paginiThe Most Influential Living Artists of 2016Gabriela RobeciÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patito AmigurumiDocument7 paginiPatito AmigurumiElisa Camargo100% (3)

- Lean On Me (ESPAÑOL) ORIGINAL by LA TOC RES-QDocument19 paginiLean On Me (ESPAÑOL) ORIGINAL by LA TOC RES-QCristianperezfÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 Microphone 2020Document15 pagini2 Microphone 2020yap yi anÎncă nu există evaluări

- Block Diagram and Effect Presets of EURORACK UB1204FX-PRODocument2 paginiBlock Diagram and Effect Presets of EURORACK UB1204FX-PROAndreea IonescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Smartstep 2 Servo Motors: @, R88M-Gp@Document6 paginiSmartstep 2 Servo Motors: @, R88M-Gp@HammadMehmoodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Local Train Ticketing Android Project Overview:: Andorid Software Development Kit (SDK)Document2 paginiLocal Train Ticketing Android Project Overview:: Andorid Software Development Kit (SDK)faizaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Valid Documents ListDocument1 paginăValid Documents ListAvijit MukherjeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Newspaper Project Websites 23Document4 paginiNewspaper Project Websites 23rini hinkleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ba400 Series: Maintenance ManualDocument101 paginiBa400 Series: Maintenance ManualDanijel DelicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pre Intermediate Test 1Document2 paginiPre Intermediate Test 1МаринаÎncă nu există evaluări

- ESL Brains Fancy A Game TV 2475Document6 paginiESL Brains Fancy A Game TV 2475Yamila FranicevichÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5013POP Module Handbook Updated Sep 11Document39 pagini5013POP Module Handbook Updated Sep 11Jasmina MilojevicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Statement For Ufone # 03335127990: Account DetailsDocument8 paginiStatement For Ufone # 03335127990: Account DetailsIrfan ZafarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Music Forms of The Baroque PeriodDocument6 paginiMusic Forms of The Baroque PeriodLinkoriginal100% (2)

- 20 Pirate Characters in One Piece Anime and Their AbilitiesDocument3 pagini20 Pirate Characters in One Piece Anime and Their AbilitiesCheene Dela RosaÎncă nu există evaluări

- TOEFL Junior: Sample QuestionsDocument7 paginiTOEFL Junior: Sample QuestionsNgat HongÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sams ComputerFacts - Apple IIeDocument73 paginiSams ComputerFacts - Apple IIeOscar Arthur KoepkeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mushoku Tensei - Volume 21 - Young Man Period - Cliff Chapter (Baka-Tsuki) (Autogenerated)Document764 paginiMushoku Tensei - Volume 21 - Young Man Period - Cliff Chapter (Baka-Tsuki) (Autogenerated)glen biazonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Europass CV - English Cosmin Ion MunteanuDocument9 paginiEuropass CV - English Cosmin Ion MunteanuMihaela MtnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seat Leon 2020 SSP177 - ENDocument76 paginiSeat Leon 2020 SSP177 - ENPaulo Marcelo100% (3)

- Blood Type AbDocument5 paginiBlood Type Absol43412Încă nu există evaluări

- Cooking Frozen and Canned VegetablesDocument7 paginiCooking Frozen and Canned VegetablesLeonor Miras Lagunias67% (3)

- Contemporary Philippine Arts from the Regions: Materials and TechniquesDocument11 paginiContemporary Philippine Arts from the Regions: Materials and Techniquesgroup 6Încă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4: Emotion ExpressionsDocument48 paginiChapter 4: Emotion ExpressionsMichael Z. Newman100% (12)

- Harman Kardon DVD 39 230 Service Manual PDFDocument113 paginiHarman Kardon DVD 39 230 Service Manual PDFtantung phamÎncă nu există evaluări