Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Flaubert Wrting and Negativity

Încărcat de

effy27Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Flaubert Wrting and Negativity

Încărcat de

effy27Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Flaubert: Writing and Negativity Author(s): Christopher Prendergast Reviewed work(s): Source: NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, Vol. 8, No.

3 (Spring, 1975), pp. 197-213 Published by: Duke University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1345103 . Accessed: 28/04/2012 19:09

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Duke University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction.

http://www.jstor.org

and Flaubert: Writing Negativity

CHRISTOPHER PRENDERGAST In the opening pages of L'Education sentimentale we encounter the following two sentences: "La campagne etait toute vide. II y avait dans le ciel de petits nuages blancs arretes, et l'ennui, vaguement repandu, semblait alanguir la marche du bateau et rendre l'aspect des voyageurs plus insignifiant encore." The context will, of course, be recalled: Frederic Moreau is on a boat travelling up the Seine from Paris to Nogent and it is on this journey that he will make the decisive encounter of his life with Marie Arnoux. On a hasty reading the sentences appear as a relatively straightforward enumeration of descriptive elements, particularizing the landscape, indicating the movement of the boat, evoking the general aspect of the passengers on board. A more attentive reading will, however, yield further, more significant qualities; above all the evident care taken over the composition of the sentences: the attention to structure and rhythm in a conscious attempt to create through shape and sound a kind of plastic image or correlative of their semantic content. There are, for example, the "blank" quality of the first sentence, the characteristic use of the ternary period, the strategically placed "vaguement repandu," the weighty, arresting sound of "alanguir," the placing of "encore" after instead of (as is more usual) before "plus insignifiant," again for obvious rhythmic and sonorous effect. Furthermore, if we go back to the sentences after we have read the whole novel, we shall find that, through their power of suggestion, they reach beyond the immediate context to integrate symbolically with some of the major themes of the novel: thus, the motifs of void and immobility, boredom and insignificance, adumbrate many of the central realities the hero will encounter in the course of his "education." Finally, the sentences could be read in another way: they could be said to reflect, at the micro-level, the principles governing the overall form of the book. As Jean-Pierre Richard has argued, in Litterature et sensation, the creation of form in Flaubert's fictions proceeds from a tension between the principles of fluidity and solidification, dissolution and petrification; from an urge to yield to what is apprehended as the unstructured, dissolving rhythms of life and an impulse to impose order and coherence on those rhythms. Our extract, both in the content of its dominant images (flux and immobility) and in its own formal structure (at once free-flowing and yet harmoniously arranged) may be said to reflect the larger dialectic of formal elaboration in Flaubert.1

1 The highly general nature of this essay needs to be stressed; it is intended simply to open up a perspective that will be more fully developed elsewhere through a detailed analysis of L'Education sentimentale and Bouvard et Pecuchet.

198

NOVELISPRING

1975

I have begun with this brief analysis, because to read a short extract like this and to grasp its implications is to realize what a complex process a proper reading of Flaubert involves; how, even or perhaps above all, at the minimal levels of the text, he systematically mobilizes and exploits devices of the greatest technical sophistication in the service of the novel form. "Quelle chienne de chose que la prose," he writes in the Correspondance, "Can'est jamais fini, il y a toujours a refaire. Je crois pourtant qu'on peut lui donner la consistance du vers. Une bonne phrase de prose doit etre comme un bon vers, inchangeable, aussi rhythmee, aussi sonore. Voila du moins mon ambition (il y a une chose dont je suis sur, c'est que personne n'a jamais eu en tete un type de prose plus parfait que moi; mais quant a l'execution, que de faiblesses, que de faiblesses, mon Dieu!)." 2 The pursuit of this ideal and all that it involved-the famous "affres du style," the exhausting quest for "la belle phrase" 3-become the central objective of Flaubert's whole existence. In a letter to Louise Colet in 1851, when Flaubert was immersed in the writing of Madame Bovary, he declares: "Je suis un homme-plume. Je sens par elle, a cause d'elle, par rapport a elle et beaucoup plus avec elle." This is by no means a mere literary hyperbole, but a seminal remark, for it represents one of the first fully serious attempts by a writer to define himself exclusively in and through the practice of writing. In the most immediate and profound sense Flaubert is his writing: "L'Art, c'est l'Art seul qui compte" echoes like a refrain throughout the Correspondance and is the measure of Flaubert's intensity of commitment to the literary enterprise; responsible for the image that comes down to us of Flaubert the exemplary artist, totally dedicated to the literary vocation; of the writer who insisted, through both affirmation and example, that the novel is a mode of supreme artistic seriousness, demanding responses of intelligence and sensibility as discriminating as those demanded by any other high literary form.

2 "What a bitch of a thing prose is, you're never finished, there's always something to be redone. I believe nevertheless that one can give it the consistency of verse. A good prose sentence must be like a good line of verse, unalterable, as rhythmical, as sonorous. There at least is my ambition (there's one thing of which I'm certain, no-one has ever conceived of a more perfect type of prose than I; but as for the execution of the idea, my God, what failings, what failings!)" 8 As Roland Barthes has observed, the anguished struggle with the sentence constitutes the very heart of the Flaubertian aesthetic: "Pour Flaubert, la phrase est A la fois une unite de style, une unite de travail et une unite de vie, elle attire l'essentiel de ses confidences sur son travail d'ecrivain." "Flaubert et la phrase" in Nouveaux essais critiques (Paris: Points, 1972, p. 142). In developing his reflection upon the significance of the sentence in Flaubert, Barthes furthermore offers an insight that is of major importance in the context of the present article. Adapting from linguistics the model of paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations to an analysis of Flaubert's famous "corrections," Barthes points out that the majority of Flaubert's alterations to the sentence are of a syntagmatic (i.e. combinatorial) rather than paradigmatic (i.e. substitutive) order, and, more specifically, at the syntagmatic level, they tend more towards expansion than towards contraction of the sentence. In other words, for Flaubert the essential problem posed by the sentence is that of its theoretical open-endedness, and it is in this sense that Barthes can speak of Flaubert as being haunted by "le vertige d'une correction infinie." In more generalized terms, this shows that for Flaubert, the problem of "form" (what Flaubert generally refers to as the aspiration to "perfection") is fundamentally a problem of closure, of arresting the theoretically infinite processes of language. In this respect we may perhaps speak of the Flaubert text as one that hovers between "closure" (striving for the moment of "perfect" expression) and "infinity" (engaged in the infinite play of language); hence the deeply ambivalent impression generated by a reading of Flaubert's major fictions: on the one hand, they present themselves as completed, fully wrought artifacts, and, on the other hand, as ceaseless play of forms, as activity of writing that never comes to rest in some fixed set of patterns and meanings; as, precisely, in Barthes' words, "des ensembles a la fois structures et flottants."

CHRISTOPHER

PRENDERGASTIFLAUBERTIAN

NEGATIVITY

:199

Yet it is precisely that intensity of artistic commitmentwhich poses what we of might call the "problematic" Flaubert,a problematicof writing that is by no means unique to Flaubert,but which is both acutely present in his work and also historically decisive in the sense that it initiates, in the second half of the nineteenth century, a profound change or break within literature that lays the foundationsfor the emergenceof one of the most importantmoments of the modern literary consciousness. For it has often been suggested that the heroic energiesinvested by Flaubertin the quest for the perfect literaryform represents a certain fetishism of form, a displacementinto the cult of Form of a radical failure of the mind to engage with "life" itself; a reificationof the literaryobject which, although formally perfect, carries within it a certain structure of deadness, a kind of spiritual inertness or impoverishmentthat arises directly out of the abstractionof Form as an absolute value in itself from what might loosely be called the "human context" of literature.As Henry James once put it, in an essay to which we shall returnlater, there is in Flaubertwhat seems to many to be a troubling, a disabling disjunction between what James calls the "large artistic consciousness" and the "meager human consciousness." Thus, for example, if we turn to the letters written during the composition of Madame Bovary,we cannot fail to be forcibly struckby the way in which the huge artistic effort is paradoxicallyaccompaniedby a violent and prolonged aversion to the human subject matter of that effort: Croyez-vous que cette ignoble realite dont la reproductionvous d6goute ne me fasse pas tout autant qu'a vous sauter le coeur. Si vous me connaissiez

d'avantage, vous sauriez que j'ai la vie ordinaire en execration. . . . On me

croit epris du reel, tandis que je l'execre:car c'est en haine du realismeque j'ai nausees, et la difficulted'ecriretant de choses si communesencore en perspective m'epouvante.4 entrepris ce roman. . . . La vulgarite de mon sujet me donne parfois des

Fromthese comments (and there are many others like them) it can be seen there-' fore that Flaubert's insistence on the autonomy and the purity of literary "form" rests, in part at least, on an experienceof radical loss or separation-a dissolution of what had hitherto been the assumption of a more or less unproblematicalrelationship between literature and "life," art and "reality." In this perspective,Art (that is to say, Form)does not copy life, interpretlife, serve life, embellish life-to bring into play some of the traditional views on the function of art-it replaceslife. In its perfectedautonomy,it is at once a rejection and a substitution.As Flaubertputs it in the Correspondance: seul moyen de "Le n'etre pas malheureux,c'est de t'enfermer dans l'Art et de compter pour rien

4 "Do you believe that this ignoble reality, the reproduction of which disgusts you, doesn't turn my stomach as much as it does yours? If you knew me better, you would know that I execrate ordinary life .... People think I am enamored of the real, whereas I loathe it: for it is out of hatred of realism that I've embarked upon this novel .... The vulgarity of my subject sometimes fills me with nausea, and the prospect of the difficulty of writing so many more commonplace things fills me with horror."

200

NOVEL SPRING

1975

tout le reste. ... La vie est une chose tellement hideuse que le seul moyen de la supporter est de l'eviter. Et on l'evite en vivant dans l'Art." In other words, the intensity of the specifically aesthetic commitment in Flaubert inscribes itself under the sign of a huge negativity, an act of refusal that seems at bottom to be an existential refusal of the "real" itself. As early as 1846 Flaubert wrote to Maxime du Camp: "J'ai eu, tout jeune, un pressentiment complet de la vie. C'etait comme une odeur de cuisine nauseabonde qui s'echappe par un soupirail. On n'a pas besoin d'en avoir mange pour savoir qu'elle est a faire vomir." 5 And this is an attitude that, in varying forms, seems in essence never to have left him: Je n'ai plus ni convictions, ni enthousiasme, ni croyance. . . . Sous mon enveloppe de jeunesse glt une vieillesse singuliere. Qu'est-ce donc qui m'a fait si vieux au sortir du berceau, et si degoute du bonheur meme avant d'y avoir bu? Tout ce qui est de la vie me repugne: tout ce qui m'y entratne et m'y plonge m'epouvante. Je voudrais n'etre jamais ne ou mourir. ... 7'ai la vie en haine. Le mot est parti, qu'il reste. Oui, la vie, tout ce qui me rappelle qu'il faut la subir. . . . Le seul moyen de vivre en paix, c'est de se placer tout d'un bond au-dessus de l'humanite entiere et de n'avoir avec elle rien de commun qu'un rapport de l'oeil. . . . La vie n'est tolerable qu'a la condition de n'y jamais etre. ... J'aime a voir l'humanite et tout ce qu'elle respecte, ravale, bafoue, honni, siffle. 6 This conflation of remarks from the Correspondance (and there are many others that could be added) would seem therefore to represent an attitude that, within certain perspectives, is a singularly unpromising one for a novelist; it seems to speak fairly decisively of a radical paralysis of the spirit, of a sensibility totally invaded and vitiated by a peculiarly sterile form of ironic awareness, of cynical contempt for the human experience that must of necessity constitute the subject matter of the novelist's work. In the light of observations such as these, and to the extent that they are relevant to the kind of literature Flaubert produced, it may therefore be in no way surprising to witness across a whole range of otherwise quite different critical traditions, varying from, say, the Continental Marxist tradition of Lukacs and Sartre to the Anglo-American tradition of Henry James and F. R. Leavis, the emergence of a common suspicion of or active hostility to Flaubert. Indeed it may be worth briefly rehearsing here the characteristic responses of two of the main representatives of these two different traditions: Lukacs and James.

6 "I had while quite young a complete presentiment of life. It was like a nauseous kitchen-smell escaping

through a ventilator. One has no need to have eaten anything of it to know that it will make you sick." 6 "I no longer have either convictions, or enthusiasm or belief. . . . Beneath my envelope of youth there lies a peculiar oldness. What is it therefore that has made me so old right from the cradle and so disgusted with the cup of happiness even before having drunk from it? Everything of life repels me. I should like I hate life. There, the word is out and let it stand. Yes, life, never to have been born, or to die. ... everything which reminds me that it has to be undergone .... The only way to live in peace is by placing oneself at a leap above the whole of humanity and to have nothing in common with it other than a purely observer's relationship. . . . Life is tolerable only on condition of never being in it. ... I like to see humanity, and everything that it respects, debased, flouted, reviled, hissed at."

CHRISTOPHER

PRENDERGAST|FLAUBERTIAN

NEGATIVITY

201

In Studies in European Realism, Lukacs attempts, from within a particular Marxist perspective, to diagnose a "crisis of realism" in which the example of Flaubert is of central importance. Thus Lukacs writes: The really honest and gifted bourgeois writers who lived and wrote in the period following upon the upheavals of 1848 . .. remained mere spectators of the social process. . . . The change in the writer's position in relation to reality led to the putting forward of various theories, such as Flaubert's theory of The new type of realist turns into a specialist of literary impartiality. ... . . . who makes a "speciality" of describing the social life of the expression present. This alienation has for its inevitable consequence that the writer disposes of a much narrower and more restricted life-material than the old school of realism. . If we wish to summarize the principal negative traits of Western European realism after 1848 we come to the following conclusions: First, that the real, dramatic and epic movement of social happening disappears and isolated characters of purely private interest, characters sketched in only a few lines, stand still, surrounded by a dead scenery described with admirable skill. Secondly, the real relationships of human beings to each other, the social motives which, unknown even to themselves, govern their actions, thoughts and emotions, grow increasingly shallow; and the author either stresses this shallowness of life with angry or sentimental irony, or else substitutes dead, rigid, lyrically inflated symbols for the missing human and social relationships. Thirdly (and in close connection with the points already mentioned): details meticulously observed and depicted with consummate skill are substituted for the portrayal of the essential features of social reality and the description of the changes effected in the human personality by social influences.7 This analysis is far from elegant, but the essential point should be clear. What Lukacs tries to do is to link the so-called temperamental disability in Flaubert (his inveterate cynicism) to a wider crisis of literary culture seen as springing from the decisive failure of the 1848 Revolution. After 1848, there appears in literature, and in particular in the novels of Flaubert, a certain deadness, a fundamental alienation of literature from life, the literary imagination being no longer engaged, as it was in the time of Balzac and Stendhal, in living social processes, but rather approaching the world, as it were, entirely from the outside. We are confronted with a kind of inert mass of superficial, meaningless facts to be recorded with dispassionate or ironic indifference; an imagination which, as such, becomes objectively complicit with or symptomatic of the processes of trivialization and dehumanization at work within that society. If we turn now to our representative of the "liberal" critical tradition, Henry

7 Georg Lukacs, Studies in European Realism (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1964), pp. 141-44.

202

NOVELISPRING 1975

James and the essay on Flaubert written in 1902, we find an argument which, although in technical terms quite different, is in its general response to Flaubert strikingly similar to that elaborated by Lukacs. Discussing the role of "point of view" in Madame Bovary and L'Education sentimentale, James advances a number of criticisms of the quality of the consciousness at the center of each novel, in a manner that directly implicates the quality of the vision of life offered by the author: Our complaint is that Emma Bovary . .. is really too small an affair .... She associates herself with Frederic Moreau in L'Education to suggest for us a question that can be answered, I think, only to Flaubert's detriment. Why did Flaubert choose, as special conduits of the life he proposed to depict, such inferior, and in the case of Frederic, such abject human specimens? . . . If I say that in the matter of Frederic at all events the answer is inevitably detrimental, I mean that it weighs heavily on our author's general credit. He wished in each case to make a picture of experience-middling experience, it is trueand of the world close to him, but if he imagined nothing better for his purpose than such a heroine and such a hero, both such limited reflectors and registers, we are forced to believe it to have been by a defect of his mind. And that sign of weakness remains even if it be objected that the images in question were addressed to his purpose better than others would have been: the purpose itself then shows as inferior .. .8 The crucial emphasis here then is that Emma and Frederic, as the central "registers" of the novels, are simply "too abject and inferior" to sustain our interest. But this is not just a matter of a "technical" error on Flaubert's part; the matter goes much deeper. For James fully recognizes that the mediocrity of Emma and Frederic is consciously intended by Flaubert and that to criticize Frederic's and Emma's stature as fictional characters is, finally, to criticize Flaubert's own intentions ("the purpose itself then shows as inferior"). In other words, James is asserting that Flaubert's insistent concern with banality and triviality derives from a major limitation in sensibility, a fundamental impoverishment at the heart of Flaubert's outlook. As he observes later in the essay: Might he not have addressed himself to the human still otherwise than in L'Education. . . . When one thinks of the view of the life of his country, of the vast French community and its constituent creatures, offered in these productions, one declines to believe it could make up the whole vision of a man of his quality. Or when all was said and done, was he absolutely and exclusively condemned to irony? . . . His gift was of the greatest, a force in itself, in virtue of which he is a consummate writer; and yet there are whole sides to life to which it was never addressed and which it apparently quite failed to suspect as a field of exercise. (pp. 210-11) For James therefore-to

8 Henry James, "Gustave

return to a formula introduced earlier-there

in The House of Fiction (London, 1962), pp. 199-200. My emphasis.

is in

Flaubert"

CHRISTOPHER

PRENDERGASTIFLAUBERTIAN

NEGATIVITY

203

Flaubert a gulf between the "comparatively meager human consciousness" and the "absolutely large artistic consciousness" (p. 210). This last phrase calls to mind a similar opposition in Lukacs when, in connection with Flaubert, he speaks of "the contradiction between the subtly artistic presentation of the subject and the dreary tedium of the subject itself" (p. 170). We find therefore, from quite different backgrounds and intellectual orientations, a curious convergence of James and Lukacs where Flaubert is concerned; from quite different initial standpoints, they arrive at a more or less common conclusion: namely, that for all their formal "beauty," Flaubert's novels suffer from a certain spiritual emptiness; beautiful, but dead, or in Malraux's memorable phrase, "de beaux romans paralyses." On their assumptions, the arguments of both Lukacs and James are extremely powerful ones, and have to be taken seriously by anyone interested in Flaubert in terms other than those of mere belletristic chit-chat or academic fact-grubbing. Yet I think it has to be argued that such a reading of Flaubert's negativity is in fact founded on a radical misapprehension, a failure to enter into the real play of the Flaubert text, that play which, in its vertiginous dissolution of established orders of discourse and forms of knowledge, opens up the whole terrain of the modern literary adventure. To appreciate this, we need to work within a theoretical space that is situated beyond the emphases of "humanism" (whether Marxist or liberal) and from within which one can see the "negativity" of the Flaubert text as articulating one of the most authentic and liberating kinds of "criticism" -"criticism" in Nietzsche's sense of the term. That is, we need to see the text as operating a critical interrogation of the ways in which an intelligible world is both created and consolidated; an interrogation of those forms of intelligibility, of understanding and interpreting "reality," which in the culture that has form-ed them go unacknowledged as "forms," but are offered instead as the repositories of absolute truth (an interrogation that will, of course, include the discourse of humanism to the extent that this too has suffered from a large degree of petrification). One way of formulating this would be perhaps to say that Flaubert's negativity is concerned not with a refusal of the real but with a refusal of the Real. This might seem to be little more than a mystifying play on words, but in fact the difference in emphasis is crucial. It is a way of saying that what the text operates is a subversion of fixity, a negation of fixed, absolute or, better, stereotyped definitions of reality. What fascinates Flaubert, what animates and nourishes the negative impetus in his imagination, is the figure of the Stereotype, those diverse forms of attitude, behavior, language, all the activity of which is to transform provisional constructs of reality into the stereotyped certitudes of absolute Truth. In this sense, it is preferable to speak of the Flaubert text not as "destructive" (in the sense of some blind nihilistic rage), but, adopting a term from Jacques Derrida, as "de-constructive," 9 as systematically decon9 Cf. Derrida's reference to the idea of an "6criture" that will operate "la d6-construction de toutes les significations qui ont leur source dans celle de logos. En particulier la signification de verite." De la grammatologie (Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1967), p. 21. For the Malraux phrase, see A. Jenkins, "Flaubert," French Literature and its Background (Oxford University Press, 1969), p. 52.

204

NOVELJSPRING 1975

structing all those particular constructions of reality that are hypostasized, uncritically and complacently, as the Real tout court, the Real in some absolute, fixed sense. In order to focus more clearly the significance of this basic discrimination, I should like to cite three brief remarks from the Correspondance, for they seem to me to contain the very core of Flaubert's approach to the problematic relationship between writing and "reality": Je ne crois seulement qu'a l'eternite d'une chose, c'est a celle de l'Illusion, qui est la vraie verite. Toutes les autres ne sont que relatives. . . . II n'y a pas de Vrai, il n'a y a que des manieres de voir. . . . Avez-vous jamais cru a l'existence des choses? Est-ce que tout n'est pas une illusion? II n'y a de vrai que les "rapports," c'est-a-dire la faqon dont nous observons les objets.l0 The key terms in this set of remarks are Illusion,Vrai, manieres de voir, rapports. Set in both context and conjunction, what Flaubert seems to be expressing through them is this: all Reality is Illusion in that "reality" is never a given, fixed entity pre-existing and immediately transparent to the consciousness that simply "apprehends" or "registers" it, but is rather a construction of consciousness, the production of a particular "maniere de voir." What, at any given moment or in any given context, is known and offered as "reality," as the intelligible world (for, as Barthes has observed, there is no reality except that which is intelligible),1l is always a construction of reality, generated by a particular "way of seeing" and organized in the form of a created system of relationships between things. In other words, perception and understanding, or more generally, the activity of consciousness-and it is this which makes Flaubert's emphasis so strikingly modern-is not reflective, but constitutive; it does not "reflect" reality as an already given, but constitutes that reality; it constructs an intelligibility, a "truth" through the act of inaugurating and consolidating a system of "rapports" in terms of which things are made to cohere to form a comprehensible world ("il n'y a de vrai que les rapports"). It goes without saying, of course, that the status of this "vrai," because it is brought into being through a system of relations established by a constitutive act of consciousness, is relative rather than absolute, conventional rather than natural, formal rather than substantial. What is known as the "true" or the "real" is, fundamentally, a matter of forms of intelligibility,l2 of constructions which, as is witnessed by the evidence of cultural difference and historical change, are not immutable, natural entities, but are based entirely on convention, articulated through conventionalized codes of

10 "I believe in the eternity of only one thing, it is that of Illusion, which is the only true truth. All the others are but relative .... There is no Truth, there are only ways of seeing .... Have you ever believed in the existence of things. Is it not that all is an illusion? The only thing that is true is 'relations, that is to say, the manner in which we observe objects." 11 "il n'y a de reel qu'intelligible," Elements de Semiologie (Paris, 1964), p. 106. 12 That Flaubert understood that an intelligibility is always a matter of forms is clear from the remark in the Correspondance: "L'Idee n'existe qu'en vertu de sa forme. Suppose une idee qui n'ait pas de forme, c'est impossible; de meme qu'une forme qui n'exprime pas une idee."

CHRISTOPHER

PRENDERGASTIFLAUBERTIAN

NEGATIVITY

205

knowledge and understanding. To put it another way, in so far as they are based on specific regulative codes and conventions, subject to variation and transformation, all systems of intelligibility are fundamentally arbitrary. It is the recognition of the arbitrariness of any given intelligibility that is important, and it is this recognition that yields the real significance of Flaubert's remark that it is "illusion" which constitutes the "vraie verite." All systems, all forms of intelligibility are "illusory" in the sense that they are arbitrary constructs, fictional inventions, regulated by internal codes and conventions and therefore with no claim whatsoever to any privileged (that is, "natural") ontological status. Beneath and pre-existing the play of human constructions across history and culture, there is no fixed "truth" with which one of these constructions might happily coincide; since they are all arbitrary, what lies beneath them is not a plenitude of original sense, but a void, not a presence but an absence, in short, the Neant. The apprehension of the "neant," of the void which lies beneath and continually threatens the fragility of human constructions of reality, is a central Flaubertian experience and accounts for a great many of the controlling image patterns of his fictions (in particular, those of dispersal, erosion, disintegration).l3 Indeed one might speak here of the experience of a certain vertige du neant, an experience composed of both exhilaration and panic before, to use one of Barthes' phrases, the perpetual "glissement du sens," a perpetual leakage through which all possibility of stable significance slides away into nothingness. Naturally, such an experience is one that the human mind does not customarily like to confront; it will prefer the illusory assumption of stability to the troubling reality of instability. And for the more marked forms of this turning away from the "neant," Flaubert has a name: "la betise." Flaubert's life-long fascination with the various modes of human "betise" is, of course, well known, and the intensity of that fascination may be simply indicated here by quoting from the letter he wrote in Raoul-Duval in 1879 while engaged in the writing of that supreme exposure of "la betise," Bouvard et Pecuchet: Vous me parlez de la betise humaine, mon cher ami, ah! je la connais, je l'etudie. C'est la, l'ennemi, et meme il n'y a pas d'autre ennemi. Je m'acharne dessus dans la mesure de mes moyens. L'Ouvrage que je fais pourrait avoir comme sous-titre Encyclopedie de la betise humaine. L'entreprise m'accable et mon sujet me penetre.14 The definitions, descriptions, and illustrations that Flaubert gives of "la betise" are, of course, legion,l5 but unquestionably the most important is his observation,

13

Within the perspectives of "thematic" criticism, these image patterns have been analyzed in detail by Jean-Pierre Richard, Litterature et sensation (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1954). 14 "You speak to me of human stupidity, my dear friend, ah, there's the enemy and indeed there is no other enemy. I'm going at it tooth and nail to the best of my ability. The work I am writing could have as a sub-title Encyclopedia of Human Stupidity. The enterprise overwhelms me and my subject impregnates me." 15 For a compilation of Flaubert's diverse remarks on "la betise," see Genevieve Bolleme's introductory essay ("Flaubert et la betise") to her edition of Le second volume de Bouvard et Pecuchet (Paris:

Denoel, 1966).

206

NOVELISPRING

1975

"la betise consiste a vouloir conclure. .. ." It consists, that is, in the desire to arrest the infinite play of human constructions of reality, to fill the void with a plenitude of immediately available sense. And, although frequently offered as a universal condition of the human mind ("nous ne souffrons que d'une chose: la Betise. Mais elle est formidable et universelle"), it is "betise" in this sense of arrestation that Flaubert sees as the distinctive mark of his own bourgeois society ("Dans quel abtme de betise l'epoque patauge! II me semble que l'idiotisme de l'humanite arrive a son paroxysme"). In Flaubert's critical vocabulary, "bourgeois" and "bete" are virtually synonymous. What marks the bourgeois is the unshakable refusal to confront the void, the urge to draw over the void a veil fabricated from a bland and nauseous tissue of reassuring, instantly consumable meanings, to create a world with a totally smooth surface, without leaks and gaps, and of which, in his preening self-confidence, massive complacency, and opinionated fixity, the supreme representative in Flaubert's novels is Homais of Madame Bovary. Here, then, in the opposition of void and plenitude, panic and complacency, skepticism and stupidity, is the core of Flaubert's "negative" vision, the source of Flaubert's profound insight into his society and the crux of the critique of nineteenth-century civilization that his work offers. In order further to discuss the implications of this insight and this critique for the kind of fictional writing Flaubert produces, I want to return for a moment to Flaubert's remark about the "maniere de voir" and to suggest a specific link between this remark and the distinctive mode of social criticism developed in the novels. In the context of Flaubert's preoccupation with "la betise," one of the possible references of the observation "il n'y a pas de Vrai, il n'y a que des manieres de voir" is to those specifically social and cultural forms of consciousness which offer general and collective representations of reality, as distinct from purely individual ones. Typically, the operations of social and collective consciousness are the processes through which society as a whole constructs, interprets, and legitimates its own reality as, precisely, Reality. This phenomenon is, of course, well known to the sociology of knowledge. For instance, in their book The Social Construction of Reality, Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann comment extensively on the tendency inherent in all societies to "naturalize" the reality they have historically constructed, the tendency to convert a world dynamically produced by a specific socio-historical praxis into the World tout court, permanent, unalterable, natural. Thus, in the words of Berger and Luckmann, although "social order is not part of the 'nature of things' and . . . cannot be derived from the 'laws of nature,' social order exist[ing] only as a product of human activity," nevertheless the social world is habitually experienced by its inhabitants "in the sense of a comprehensive and given reality confronting the individual in a manner analogous to the reality of the natural world." 16 The processes of naturalization at work within a given society are necessarily

16 Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality (London: Penguin, 1972), p. 69.

CHRISTOPHER

PRENDERGASTIFLAUBERTIAN

NEGATIVITY

207

varied and complex, but one of the essential strategies through which a socially constructed reality is internalized and maintained in consciousness as a takenfor-granted, "natural" reality is in the creation and transmission of what Berger and Luckmann call a "stock of social knowledge." This knowledge is not primarily theoretical knowledge; rather it is a diffuse ideology, a body of opinions, attitudes, beliefs, values which, through the mediation of certain forms of language, are socially objectivated as "knowledge." In short, it is the knowledge of common-sense consciousness, what the consensus of received opinion in a given society assumes and offers as Reality. It is what Aristotle called endoxon ("current opinion"), and, following Aristotle, we may perhaps call the discourse which repeats and reinforces consensus knowledge the endoxal discourse,17 the language of common-sense, the language of the stereotype, whose function is to cover a world historically produced with the mantle of the universal and the permanent and of which the classic forms are the maxim, the proverb, the platitude, the idee revue. It is with reference to these endoxal forms of language that Berger and Luckmann can write: Language becomes the depository of a large aggregate of collective sedimentations, which can be acquired monolithically, that is, as cohesive wholes and without reconstructing their original process of formation. . . . Furthermore, since human beings are frequently stupid, institutional meanings tend to become simplified in the process of transmission, so that the given collection of institutional "formulae" can be readily learned and memorized by successive generations. The formula character of institutional meanings ensures their memorability. (my emphasis)18 The central, strategic role of the idee revue in the organization of the Flaubert text is, of course, wholly familiar, and its ironic manipulation across all levels of the text serves, precisely, to dissolve the "collective sedimentations" of "formula meanings" which his society draws upon to assure its own reality as Reality. Flaubert's "social criticism" is, hence, primarily a criticism of language, of those verbal forms which generate and enshrine a stereotyped social knowledge. One way of seeing the Flaubert text is as a huge mobile space of "citations," 19 taken from that diffuse corpus of other texts which together make up the "natural

17

. . . chaque parler (chaque fiction) combat pour l'hfgemonie; s'il a le pouvoir pour lui, il s'etend partout dans le courant et le quotidien de la vie sociale, il devient dexa, nature." R. Barthes, Le Plaisir du texte (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1973), p. 47. On the connection in Flaubert's thinking between "betise" and "endoxon," see the remark inserted into the plans and sketches drawn up in 1863: "Quel est l'imbecile qui a dit ceci: 'il y a qqun qui a plus d'esprit que Voltaire, c'est tout le monde?'-pas du tout.-il y a quelqu'un de plus bete qu'un idiot, c'est tout le monde-" cit. M-J. Durry, Flaubert et ses projets inedits (Paris: Librairie Nizet, 1950), p. 94.

Berger and Luckmann, pp. 87-88. In connection with their notion of "sedimentation," it is perhaps worth

18

recalling that one of the important terms used by Derrida in his project of shattering the assumption of a fixed relation between language and "truth" is, precisely, "la de-sedimentation." De la grammatologie, 19 Literally in the case of the projected second volume of Bouvard et Pecuchet of which Flaubert wrote in the Correspondance that "il . . . ne sera compose presque que de citations."

p. 21.

208

NOVELISPRING

1975

attitude" (to use Husserl's term) of his society, citations which, as they enter the space of the Flaubertian text, are immediately de-formed, displaced, dismantled through Flaubert's numerous strategies of irony. The adventure of Flaubert's heroes and heroines is essentially a tragi-comic adventure of language, the geography of the problematical terrain they attempt to negotiate consisting of a series of stereotyped linguistic forms. The motifs of quest and travel have been frequently commented on as major thematic and structural determinants of the Flaubert novel; whether in imagination or actuality, Emma, Frederic, Bouvard, Pkcuchet are compulsive travellers. And the journey that they make is primarily a textual one; the space they travel through is a textual space in which they encounter, problematically, all the great endoxal texts of the nineteenth century-those of Romantic Love, Art, Politics, Science, Progress, those heavily naturalized verbal articulations of reality that Religion-all collapse the moment that the myths they embody are tested against experience. The subversive energy of Flaubert's writing resides largely in the joyous outplaying and undoing of the "myths" of nineteenth-century bourgeois culture. The term "myth" is used here in the precise sense in which it is used by Roland Barthes in his book Mythologies, where myth is understood as a semiological system the function of which is to disguise the ideological as the natural, a constructed reality as a permanent order of things, made for all eternity to the specifications of bourgeois man. Indeed in Mythologies Barthes explicitly refers to Flaubert's Bouvard et Pecuchet as "une veritable restauration archeologique d'une parole mythique" and to Flaubert's ironic language as the "countermythical" demystification of that speech.20 And it is here, finally, that one can perhaps arrive at a proper description of Flaubert's negativity: it is the negativity of the demystifying mythologist who plays havoc with the nineteenth-century texts of social knowledge, exposing not only the "ideas" themselves (a fairly banal operation of satire), but, more importantly, the processes whereby this socially constructed knowledge is naturalized as absolute knowledge. In other words-and it is here that we encounter the real modernity of Flaubert-his text enters, ironically and deconstructively, not only into the content of the nineteenth-century endoxal text, but also into its forms, into the processes of its

20

Barthes, Mythologies (Paris: Collection Points, 1970), p. 223. Barthes in fact sees Flaubert's attitude to the cultural codes as marked by a certain ambiguity; thus in S/Z he speaks of Flaubert's irony as "une ironie frappee d'incertitude" (p. 146), and in an interview (Signs of the Times, Cambridge, 1971) remarked, "Flaubert . . . grappled with the cultural codes; he was truly bogged down by them and . . . he tried to free himself from them by very ambiguous attitudes at once of irony and plagiarism, simulation" (p. 46). Flaubert was fascinated by the codes of nineteenth-century "knowledge" ("la betise de mes deux bonshommes m'envahit," he wrote of Bouvard et Pecuchet). But this should in no way be taken as implying any major degree of complicity with those codes. The ambiguity is not of an ethical or ideological order, but is, rather, bound up with the evident delight Flaubert experiences in playing with the cultural codes, a ludic engagement that is in fact vital to the ironic deconstruction of the codes. There is a certain pleasure to be derived from this engagement and, in his notes for Bouvard et Pecuchet, Flaubert speaks significantly of "le plaisir qu'il y a dans l'acte materiel de recopier." We should perhaps interpret the term "plaisir" here in one of the senses developed by Barthes in Le Plaisir du texte: "plaisir" as the eudemonic experience derived from inscribing oneself within the security of known and established cultural forms, set in opposition to "jouissance," the experience of vertiginous dissolution of those very forms (Le Plaisir du texte, pp. 25-28). What is most radical in Flaubert is situated on the side of "jouissance."

CHRISTOPHER

PRENDERGASTIFLAUBERTIAN

NEGATIVITY

209

own production as knowledge; in short, into the play of its codification. What is unmasked is not simply an attitude to the world, but, by a continual pointing to the social and cultural codes through which the attitude is articulated and stabilized, the claim of that attitude to a kind of natural "innocence." I have said that the activity of demystification sustained by Flaubert's writing engages with nearly all of the great endoxal texts of the nineteenth century. Perhaps the extreme point or moment of that activity is a placing in question by Flaubert's fictions of the text of the Novel itself. For in the course of the nineteenth century, the novel becomes a strongly naturalized form, deeply complicit in the establishment and consolidation of that "mythical" discourse which seeks to repress the cultural into the natural, to disguise the constitutive activity of language as immediate, transparent reflection of an already given "truth." 21 The crux of that development within the novel form is, of course, in its long association with the notion of Realism, that body of literary doctrine which, at least in its purest, most naive forms, assumes a totally unproblematical relationship between literature and "reality." Despite the view of Flaubert habitually invoked by the conventional literary histories and manuals as the high-priest of the French school of literary Realism, Flaubert's own statements on the matter impress upon us, in characteristically virulent manner, the very reverse. Thus, in a letter to George Sand he writes: "Notez que j'execre ce qu'on est convenu d'appeler le realisme, bien qu'on m'en fasse un des pontifes." The sentiment is echoed in another letter to Maupassant: "Comment peut-on donner dans des mots vides des sens comme celui-la: 'Naturalisme'? Pourquoi a-t-on delaisse ce bon Champfleury avec le Realisme qui est une ineptie du meme calibre, ou plut6t le meme ineptie?" The reasons for this dissociation are manifold and complex, but the essential point is that Flaubert, fully aware of the constitutive nature of the novel (as of all forms of language), of its dependence on a constructing, organizing "maniere de voir," sees through the central assumption of naive Realism, the positivist assumption of reality as simply "out-there," an already constituted, intelligible Reality pre-existing the text and which, in a gesture of innocent representation, the text passively "mirrors." Flaubert in fact grasps what will be the major recognition and point of reflection of the modern novel: that the claim of the "realist" novel to being, in Duranty's phrase, "l'expression reelle de tous les faits," to being an authentic "copy" of the given world, is an illusion, the function of which (as with all mythical discourse) is to disguise its real identity, which is, fundamentally, that of a writing of repetition. Flaubert sees that the novel which offers itself and is accepted as "realistic" is, in the words of Stephen Heath, nothing other than "that which repeats the received forms of 'Reality,' it is a question of reiterating the society's system of intelligibility," 22 a system that goes unacknowledged as "system" but which is assumed as being in direct

21 22

Cf. Philippe Sollers, Logiques (Paris: tditions du Seuil, 1968): "Notre societe a besoin du mythe du 'roman'. ... Le roman est la maniere dont cette societe se parle" (p. 228). Stephen Heath, The Nouveau Roman, a study in the practice of writing (London, 1972), p. 21.

210

NOVEL SPRING 1975

conformity with some absolute truth; in brief, the Novel, in so far as it proffers and confirms naturalized modes of seeing and understanding the world, is itself one of the major forms of "la betise." The vital point to be made here, however, is that this recognition by Flaubert is articulated in and through the very play of his fictions themselves, one of the marks of their originality lying, precisely, in the way that, through their own activity, they engineer a certain break or fissure in the ostensibly solid walls of classic fictional representation. For instance, the recognition is perhaps there in the projected ending of Bouvard et Pecuchet where the two heroes were to renounce their hopeless quest for the "truth" to settle for the role of "copiste," endlessly copying out all the texts which come into their hands. Both the details and the general significance of this projected ending have been the subject of much scholarly controversy, but what is certainly clear is that a large part of the copying enterprise was to have been devoted to the task of transcribing the texts of "la betise" (of which Flaubert's own Dictionnaire des idees reques would almost certainly have been one); what they were to copy were the texts of stereotyped "knowledge," that is, those endoxal texts that are themselves offered as, precisely, a "copy" of the Real. Thus, through a complex spiral of selfconscious ironies, we arrive at the absurdity of absurdities: an activity of writing that is, quite literally, a copy of a copy. And it is in that absurdity that we can perhaps read an analogue of Flaubert's critical approach to the characteristic nineteenth-century attitude to the novel. We have seen that for Flaubert, in so far as the mirror analogy is at all relevant, it is never in the sense of a direct reflection of a "reality" immediately present to the text; what, if anything, the text "mirrors" is simply another text, namely, the text of "common opinion," that which expresses the socially established verities of endoxon. To the extent that it is structured by the endoxal, the "realist" novel is therefore a secondary rather than a primary mirror, a mirror at a double remove; it is to be read as a "reflection" of what, in everyday social life, within the terms of the natural attitude, has already been read as a "reflection" of the Real. In other words, like the transcriptions of Bouvard and Pecuchet, the "realist" novel is a copy of a copy.23 Thus, in terms of the burlesque parody of Bouvard and Pecuchet's futile compilations, the negativity of the Flaubertian novel turns finally on the Novel itself, in the degree to which it has become an institutionalized discourse. Instead of the uncritical repetition and unreflecting confirmation of the stereotype, the novel of Flaubert, at its most radical moments, initiates a critical deconstruction of the very forms of intelligibility occulted by the "realist" novel. Instead of the assumption of the novel as a fixed, stable mirror, passively expressing the Real in its fullness and immediacy, Flaubert's text sets in motion a veritable play of "mirrors," 24 a network of shifting perspectives in which the "real" or the

23

24

Cf. Barthes, S/Z (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1970), p. 61: "Ainsi, le realisme . . . consiste non a copier le reel, mais a copier une copie du reel." Cf. Barthes, L'Empire des signes (Geneva, 1970), p. 106: "le miroir ne capte que d'autres miroirs, et cette r6flexion infinie est le vide meme (qui, on le salt, est la forme)."

CHRISTOPHER

PRENDERGASTIFLAUBERTIAN

NEGATIVITY

211

"true" can never be caught because it is never "there," its attempted representation perpetually displaced from one reflection to another in an endless process of formation, deformation, reformation: Emma as seen by herself, by Charles, by Rodolphe, by Leon, by Homais; Charles as seen by Emma, by Rodolphe, by a series of interpretations constructed and deHomais; Homais as seen . . . constructed in an elaborate play of significations that never comes to rest in some definitive utterance, a kaleidoscope of different versions of "reality" thrown into an ironic, self-cancelling interplay of such ferocious intensity that in the end the reader experiences a sense of panic, a radical loss of any fixed point of meaning against which he can measure and assess the different perspectives with which he has been presented. In that play of perspectives, the text operates a suspension of what Barthes, in his analysis of Balzac's Sarrasine, has called the "hermeneutic code," that code which, across such motifs as quest, mystery, paternity, etc., triumphantly unravels and reveals what the Avant-Propos to the Comedie humaine names as the "sens cache" of reality. Take, for example, the motif of travel and quest. In Balzac, the journey is always a voyage of discovery; Rastignac's journey from the provinces to Paris, from the Pension Vauquer to the Faubourg Saint Germain, entails the gradual discovery of the "laws" (what the text names as the "ultima ratio mundi") that regulate the life of his society. In L'Education sentimentale, Frederic Moreau makes a similar journey from the provinces to Paris, but, as the internal reference by Deslauriers to the model of Balzac's Rastignac makes clear25 (for the expectations generated by that model are never realized), this represents less a repetition of the motif of classic fiction than an ironic re-writing of it. For what does Frederic "discover"? His own answer to a similar question is "Rien!" 26 His journey is a journey of dispersal and erosion, a journey through structures that ceaselessly dissolve before his gaze, leading ultimately to the encounter not with a Truth but a blank, an absence, a void. Furthermore, this loss of a sense of fixity or finality in the external world, in history and society, corresponds to a similar loss in the subjectivity of Frederic. "Who is Frederic Moreau?" is a question often asked by criticism. Can he be named in the way that one can confidently name Rastignac as, for instance, the "ambitieux," the "parvenu"? Unlike the dynamic, integrated personality of the Balzacian hero, Flaubert's hero is a nullity, a void; lacking any stable center of consciousness, Frederic's interiority is an empty space traversed throughout the course of the narrative by a plurality of fragmented, dissociated impressions and sensations that never cohere to form a fully constituted subject. That lack

25

L'Education sentimentale, (Paris: ed. Garnier, 1964), p. 17: "Mais, je te dis la des choses classiques, il me semble? Rappelle-toi Rastignac dans la Comedie humaine! Tu reussiras, j'en suis sir!" 26 "L'Education sentimentale est le roman de l'apprentissage par le vide, de l'apprentissage du neant." J-P. Duquette, Flaubert ou l'architecture du vide (Montreal, 1970), p. 77. But, despite its promising title, Duquette's book is little more than an extended version of the type of thematic criticism already practiced by Jean-Pierre Richard and Victor Brombert; despite the title, it explicitly engages in a quest for what, in the preface, Duquette calls the "sens profond" of the novel and hence fails to see that what is most radical in L'Education is, precisely, the absence of a "sens profond."

212

NOVELISPRING 1975

in the consciousness of Frederic has, of course, been often used as a basis for criticism of Flaubert (we have seen this to be the core of James' criticism). But this misses what is most crucial in the creation of Frederic, for what we are witnessing here are the beginnings of that deconstruction of the full "Cartesian" subject that will be rich in implication for the formal experiments of the modern novel. Ian Watt has rightly stressed the close relation between Cartesian epistemology and the construction of the solid "character" of classic fiction.27 In emphasizing the fragmented and ultimately vacant nature of Frederic's consciousness (in the course of his "education" Frederic learns "nothing"), Flaubert directs his novel toward a subversion of one of the most elementary formal categories and conventions of the Novel: the convention of "character," that heavily naturalized literary code which assumes both the natural "essence" of the subject and its unproblematical "mirroring" by the fiction. This dismantling of what D. H. Lawrence was to call "the old stable ego," 28 with all its consequences in terms of the undoing of the consolidated discourse of the novel-as-mirror, signals the high point of Flaubertian negativity. Indeed in one of the early drafts of Madame Bovary, mirrors were to play a decisively ironic role in the ending of the novel. Flaubert planned an ending where Homais, having received the Croix de la Legion d'Honneur, was to walk into a room full of mirrors in which, bearing his decoration, he was to strut up and down contemplating himself in a triumphant act of self-confirmation. Yet, according to the draft, suddenly the exact reverse was to happen: Homais, the supreme incarnation of the endoxal, of a naturalized bourgeois ideology, massively convinced of his own reality, of himself as Reality, is seized by a sense of total panic; in the play of multiple reflections, the tissue of idees recues that is the personality of Homais dissolves before an experience of existential doubt, as he wonders whether he exists at all or is simply the arbitrary construction of another consciousness, simply a fictional construct, an illusion beneath which there is not a presence, a fixed substantial Reality, but an absence, a "neant," immediately covered by stereotyped recourse to the famous Cartesian formula: Epilogue Le jour qu'il (I') recue n'y voulut pas croire. Mr. X depute lui avait envoye un bout de ruban-le met se regarde dans la glace eblouissement.- . Doute de lui-regarde les bocaux-doute de son existence (delire. effets fantastiques. la croix repetee dans les glaces, pluie foudre de ruban rouge)-"ne suis-je qu'un personnage de roman, le fruit d'une imagination en delire, l'invention d'un petit paltoquot que j'ai vu nattre/et qui m'a invente pour faire croire que je n'existe pas/-Oh cela n'est pas possible. voila les foetus. (voila mes enfants, voila. voila)

27 28

D. H. Lawrence,

Ian Watt, The Rise of the Novel (London: Penguin, 1963), pp. 12-22. Collected Letters, ed. Harry T. Moore (London, 1962), I, 282.

CHRISTOPHER

PRENDERGAST

FLAUBERTIAN

NEGATIVITY

213

Puis se resumant, il finit par le grand mot du rationalisme moderne, Cogito,

ergo sum.29

This ending was of course never implemented, but just the fact of its existence as a project is itself of great significance. It suggests perhaps, by way of "conclusion"(!), a particular reading of a very famous Flaubertian declaration: "Ce qui me semble beau, ce que je voudrais faire, c'est un livre sur rien, un livre sans attache exterieure, qui se tiendrait par la force interne de son style." 30 The dream of the "book about nothing" has been interpreted in many ways, but in the context of the argument I have tried to develop here, we might perhaps read this as the dream which the modern novel-the novel of Proust, Joyce, Beckett, Robbe-Grillet-will attempt to realize: the novel which refuses any complicity with the hermeneutic myth of an original truth, of a signifie transcendental (to use Derrida's phrase)31 exterior to its discourse ("ce qui definit le realisme," writes Barthes, "ce n'est pas l'origine du modele, c'est son exteriorite a la parole qui l'accomplit");32 the novel which instead offers itself as generated and sustained solely by its own internal textual activity, as play of forms and "relations" in a ceaseless movement of construction and deconstruction, movement that is never "concluded" ("la betise consiste a vouloir conclure"), but which remains forever suspended over an absence.

29

"The day he received it couldn't believe it. Mr. X deputy had sent him a piece of ribbon-puts it on looks at himself in the mirror. vertigo. "Doubt about himself-looks at the drug bottles-doubt about his existence (delirium. fantastic effects. the cross repeated in the mirrors.. torrent lightning flash of red ribbon)-'am I only a character in a novel, the fruit of a delirious imagination, the invention of a mere no-body which I have seen born and who has invented me to foster the belief that I do not exist/ Oh, that's not possible. Look, there are the foetuses (there are my children, there, there).' "Then, summing himself up, he finishes with the great dictum of modern rationalism: Cogito, ergo sum." Jean Pommier and Gabrielle Leleu, Madame Bovary, nouvelle version (Paris: J. Corti, 1949), p. 129. so "What seems to me beautiful, what I should like to do, is a book about nothing, a book without external attachment and which would hold together by the internal strength of its style." 31 Derrida, De la grammatologie, p. 33. 32 Barthes, Essais critiques (Paris, 1964), p. 199.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- MFG260 Who's Who in The DC Universe #1 (OCR)Document201 paginiMFG260 Who's Who in The DC Universe #1 (OCR)Jabbahutson88% (16)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Oliver JR. Cue SheetDocument3 paginiOliver JR. Cue SheetGillianÎncă nu există evaluări

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (73)

- Harold BLOOM Critical Editions - Milan KunderaDocument181 paginiHarold BLOOM Critical Editions - Milan Kunderalokki100% (8)

- Slavic and Greek-Roman MythologyDocument8 paginiSlavic and Greek-Roman MythologyLepaJeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kate Cain - Reading Development and Difficulties - Dyslexia Guild Summer Conference 2011Document65 paginiKate Cain - Reading Development and Difficulties - Dyslexia Guild Summer Conference 2011dyslexiaaction100% (2)

- Emma Jane AustenDocument5 paginiEmma Jane AustenShinSungYoungÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Cognitive Semiotic Approach To Sound SymbolismDocument51 paginiA Cognitive Semiotic Approach To Sound SymbolismJacek TlagaÎncă nu există evaluări

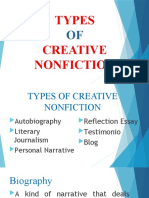

- Types of Creative Nonfiction Under 40 CharactersDocument23 paginiTypes of Creative Nonfiction Under 40 CharactersLeah Joy Dadivas100% (2)

- Evernight by Claudia Gray PDFDocument2 paginiEvernight by Claudia Gray PDFStevenÎncă nu există evaluări

- VampiresDocument13 paginiVampiresamalia9bochisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Speakout Vocabulary Extra Intermediate Unit 07Document3 paginiSpeakout Vocabulary Extra Intermediate Unit 07shasha1982Încă nu există evaluări

- The Art of AnimeDocument15 paginiThe Art of Animecv JunksÎncă nu există evaluări

- Novellanalys 20V.2Document3 paginiNovellanalys 20V.2Anonymous NubGW52Dh0% (1)

- The Book Thief Eng3u Small Group TaskDocument4 paginiThe Book Thief Eng3u Small Group Taskapi-353656564Încă nu există evaluări

- Shakespeare's 'The Winter's Tale' Explores Pastoral TraditionDocument7 paginiShakespeare's 'The Winter's Tale' Explores Pastoral TraditionTanatswa ShoniwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Book Project Percy Jackson and The Olympians The Titans Curse PDFDocument14 paginiBook Project Percy Jackson and The Olympians The Titans Curse PDFapi-447026013Încă nu există evaluări

- Court Theatre The Lady From The Sea ProgramDocument19 paginiCourt Theatre The Lady From The Sea ProgramIvan BaleticÎncă nu există evaluări

- If I Go Out TonightDocument2 paginiIf I Go Out TonightEvelynÎncă nu există evaluări

- Elements of Gothic FictionDocument1 paginăElements of Gothic Fictiondansul_codrilorÎncă nu există evaluări

- Swan LakeDocument16 paginiSwan LakeIng Jenny DavilaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The poetic meter of the given sonnet is iambic pentameter.Iambic pentameter refers to lines with five metrical feet, where each foot contains one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllableDocument15 paginiThe poetic meter of the given sonnet is iambic pentameter.Iambic pentameter refers to lines with five metrical feet, where each foot contains one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllableRon GruellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- AngeloDocument3 paginiAngeloAngelo PachecoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fantasy Fudge XDocument23 paginiFantasy Fudge XJohn ParkerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Student's Fairy Tales WorksheetDocument3 paginiStudent's Fairy Tales WorksheetKanya, 8G, 20Încă nu există evaluări

- 2016 New ReleasesDocument18 pagini2016 New ReleasesA'sHakourÎncă nu există evaluări

- How to be a good friendDocument12 paginiHow to be a good friendGrace William100% (1)

- Submission Guidelines: The Oerth JournalDocument5 paginiSubmission Guidelines: The Oerth JournalJoan FortunaÎncă nu există evaluări

- "The Poor PoetDocument2 pagini"The Poor PoetcamachocioslqbfuwÎncă nu există evaluări

- Literary Devices and Techniques ExplainedDocument2 paginiLiterary Devices and Techniques ExplainedPaul Matthew DemaineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aptis TestDocument1 paginăAptis Testmatnezkhairi0% (1)