Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

A Practical Foundation For I Rab and Tarkib

Încărcat de

lucianocomDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A Practical Foundation For I Rab and Tarkib

Încărcat de

lucianocomDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

A practical foundation for I'raab and Tarki

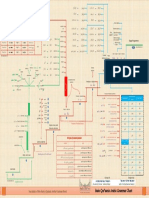

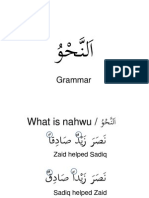

What I'm putting forth here is a method to first and foremost understand the i'rab/tarkib process. Thereafter it should help you to actually do it in practice. It goes without saying that large parts of the i'rab/tarkib process involves memorization, but I have too often seen students being able to rattle off i'rab/tarkib from memory in a sort of mechanical way without often understanding what it is that they are doing and saying. The following as you will see attempts to give you the big picture within which i'rab/trakib occurs and has to be made sense of, insha Allah. The i'rab/tarkib method that I propose basically follows the logic of the attached table entitled "Fann al-I'rab (The Art of I'rab). If you look at the table then you'll see that the expression to be analysed as per i'rab/tarkib () comprises two broad categories: the word ( )and the sentence/clause (.) These two categories can be said to form the units of i'rab/takib. The Word Moreover, the word can either be (a) mu'rab (declinable) and applies to nouns and verbs or (b) mabniyy (indeclinable) which applies to nouns, verbs and particles. Particles, thus, can only be mabniyy. (A) The Mu'rab Mu'rab nouns comprise 6 categories: (1) fully-declinable singular and broken plural [declension: dammah for raf', fathah for nasb & kasrah for jarr] (2) semi-declinable singular and broken plural [declension: dammah for raf', fathah for nasb & fathah also for jarr] (3) feminine sound plural [declension: dammah for raf', kasrah for nasb & kasrah for jarr] (4) dual [declension: alif for raf', ya' for nasb and ya' also for jarr] (5) sound masculine plural [waw for raf', ya' for nasb & ya' also for jarr] (6) five/six nouns [declension: waw for raf', alif for nasb & ya' for jarr] Mu'rab verbs comprise 3 categories: (1) sound ending mudari' stripped of the nun of tawkid and the nun of niswah [declension: dammah for raf', fathah for nasb & sukun for jazm] (2) weak ending mudari' stripped of the nun of tawkid and the nun of niswah [declension: (implied) dammah for raf', (explicit or implied) fathah for nasb & dropping of weak letter for jazm] (3) five verb forms [declension: nun for raf', dropping of nun for nasb & also for jazm]

Thus the total number of mu'rab categories (i.e. for nouns and verbs) is 9. From an i'rab/tarkib perspective, it is only these 9 categories that will be marfu', mansub, majrur (in the case of the mu'rab noun categories) and majzum (in the case of the mu'rab verb categories). To show that is marfu', mansub, majrur or majzum, the mu'rab word (which will be a real example from one of the 9 categories) will have to display a sign at its ending that shows that it referred to as 'alamat al-raf', 'alamah al-nasb, 'alamah al-jarr, and 'alamah al-jazm. These 'alamaat (signs) are either (a) asliyyah (primary/original): dammah for raf', fathah for nasb, kasrah for jarr and sukun for jazm, or (b) far'iyyah (secondary/derivative) i.e. substitute signs whenever the primary signs are not applicable. These secondary signs you should be able to infer from the 9 declensions provided in square brackets above. Furthermore, a sign of declension can either be explicit which is its normal state or implicit/implied due to something that prevents it from becoming explicit such that when that something is removed or lifted the sign will become explicit. In the case where the dammah as a sign of declension for example is explicit we say dammah thahirah and in the case where it is implied we say dammah muqaddarah. Moreover, a word can only be said to be marfu', mansub, majrur, or majzum if it occurs in a place of raf', nasb, jarr or jazm i.e. a place that causes the word to be in such a state. The places of raf' are: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) The places of nasb are: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10)

(11) (12) (13) The places of jarr are: (1) (2) (3) The places of jazm are: (1) (2) (B) The Mabniyy Mabniyy nouns comprise several categories (I've listed 16 categories on the chart some of which occur more commonly and frequently than others) but they are almost all closed classes, that is to say, classes that are composed of limited and fixed sets of items. For example, there only so many personal pronouns (dama'ir) or so many indicative pronouns (asma' isharah) in Arabic. In other words, these classes cannot be extended and expanded beyond the number of items normally listed for them. This is contrary to open classes where the number of items belonging to each class is not fixed and can therefore be increased indefinitely. With respect to the mu'rab categories they all constitute open classes with the exception of the five/six nouns. Moreover, mabniyy nouns (as is the case with all mabniyy words) considered mabniyy because of their (fairly) fixed and unchanging endings, and therefore do not have declensions as is the case with mu'rab words. Their endings could either be fixed in the form of a constant sukun, fathah, kasrah or dammah. Even though mabniyy nouns lack any sort of declension, it does not not prevent them from being able to occupy places and positions of declension. In fact, they always do and have to occupy such places (with the possible exception of one or two insignificant categories). In other words, there is generally speaking no noun (mu'rab or mabniyy) when used in a sentence except that it will have to occupy one of the places of declension listed for mu'rab nouns listed above. Whilst their endings do not change when occupying these places, and hence cannot be said to be marfu', mansub or majrur, we say instead that they are mabniyy (fixed) on such and such a sign in the mahall (place) of raf', nasb, or jarr as the fa'il, maf'ul bihi or masbuq biharf jarr, for example (we would, for example, analyse the taa' of as follows: ) Mabniyy verbs comprise three categories: (a) past verb ()

(b) imperative/verb of command () (c) present/future verb with one of the two nuns suffixed to it: the nun of tawkid and the nun of niswah () : Furthermore, these categories are all open classes as there is (potentially) no end to the number of items that can belong to each of these classes. In other words, you do not have a fixed set of madi, mudari' or amr verbs, like what you have for dama'ir, asma' isharah, asma' mawsulah, etc. In fact, new verbs are continuously being coined and added to these classes resulting in their continuous expansion. While it is true that these categories are open classes, their patterns and structural forms are fairly fixed with respect to number such that one cannot create new patterns and structural forms and add them to the existing ones. Some patterns, though, occur in Arabic usage more commonly and frequently than others, and these are the ones that get popularised in many an Arabic instructor teaching Arabic to non-native speakers, unless a particular course aims at comprehensiveness. These latter courses are often grammar heavy, and the focus is on explicit grammar teaching rather than communication and language skills development or a combination of the two. Once the verbal patterns and forms have been learnt and their usage in relation to the various pronominal suffixes has been mastered, it becomes easy to know how and with what vowel-markings (or other signs) their endings are fixed. So would be fixed with a fathah at its ending, and with a sukun, and so also and . Other parsers and analysts might give a slightly different analysis for based on different considerations and criteria but an analysis which is nevertheless valid once one understands the reasoning and logic involved. Of the mabniyy verbal categories, the past verb and verb of command do not occupy places of declension such that it can be said of them that they occur in a mahall (place) of raf', nasb or jazm for whatever reason with the exception of the past verb when it occurs in the position of the condition (shart) of a jazm-producing shart instrument, its complement (jawab shart), the position of that which is governed by the nasb-producing particle , and the position of whatever is a tabi' to one of the aforementioned. As for the present/future verb with one of the two nuns suffixed to it, it must of necessity occupy a place of declension (that is specific to verbs, and specific to the present/future verb to be more exact since it is only the latter verb type that is subject to declension which is at this stage common knowledge). Finally in the section of the mabniyy, particles as should be clear by now are all mabniyy (whether on a sukun, fathah, kasrah or dammah), and as such we do not have to qualified the term particles with mabniyy as we've done in the sections dealing with mabniyy nouns and mabniyy verbs. In addition, particles are never said to occupy places of declension at all. In their case, as well as the past verb and verb of command above, we say ( there exists no place for it in terms of declension). It is generally held that the number of particles in Arabic is

80. Of these 80 particles, 19 particles are said to share their form with nouns, and 3 with verbs an aspect that makes their analysis quite tricky. While some particles possess one and only one function, others have quite diverse usages and functions which only adds to their already existing elusiveness and trickiness. A case in point is the particle/noun word which, both as a particle and as a noun, has diverse usages and functions. This state of affairs has caused some scholars to write works entirely devoted to particles. As a side note, there is also a class of nouns (and verbs) that displays the same elusive nature and tricky character of particles, and are often discussed and treated as a whole under the generic term of adat (instrument) or adawat (instruments). It is precisely this topic of adawat to which the first section of Ibn Hisham's famous Mughni al-Labib 'an Kutub al-A'arib is dedicate which he calls al-mufradat under which he treats the particles and those nouns which have a similar meaning and function. I'm purposely elaborating this point here because of the importance that it holds for i'rab/tarkib. In fact, Ibn Hisham's above-mentioned magnum opus is an entire book devoted to the topic of i'rab/tarkib as is clear from the title. If the first section of the al-Mughni is devoted to particles and other words that possess particle-like traits, then the section is devoted to sentences and pseudo-sentences/sentence-like expressions (i.e. prepositional phrases), and it is to this topic that we now turn. The Sentence/Clause The minimum composition of a sentence/clause is a verb and its agent/deputy agent or a subject and its predicate. These are also your two major sentence-types: verbal and nominal. Other sentences/clauses are basically variations upon these two. It is your analysis of individual words that enables you to arrive at and identify sentences and clauses. Whenever you have a verb there is always going to be a verbal sentence/clause involved once you have identified its agent or deputy agent, etc. Likewise, whenever you identify a noun as the subject it is always going to result into a nominal sentence/clause once you find its predicate. Of course, and and their sisters yield an ism and a khabar which in origin are a subject and predicate, except that in the first instance it has been operated on by an incomplete verb ( ) and in the second instance by a particle. Once you have identified a sentence/clause, its analysis follows. Its analysis as is clear from the chart is based on whether or not it has a place with respect to declension. What this means is that a sentence/clause either occupies the position of declension of an individual word (noun or verb), in which case it is said to have a place with respect to declension, or it does not occupy the position of declension of an individual word (noun or verb), in which it is said not to have a place with respect to declension. The primary state of the sentence/clause is not to have a place with respect to declension , but only gains such a place by virtue of it occupying the place of declension of an individual word, and there are 7 such places of declension which give rise to seven types of sentence/clause as listed in

the table. The following are the 7 places of declension which a sentence/clause can occupy giving it the status of a sentence that has a place of declension. From these 7 places of declension you can infer the 7 sentence/clause types as per the table: (1) the khabar (2) the hal (3) the maf'ul (bihi) (4) the mudaf ilayh (5) the place after the fa' or itha al-fuja'iyyah as the jawab of a shart jazim (6) the tabi'ah (follower) of a individual word that itself has a place in declension (7) the tabi'ah (follower) of a sentence/clause that has a place in declension As is obvious, all of these places belong originally to individual words but by virtue of sentences/clauses occupying these places they acquire the declension value that these places hold. In this regard, they are almost like mabniyy words which merely occupy these places without undergoing the requisite changes that these places are meant to produce at the endings of words. Even though the primary state of the sentence/clause is not to occupy places of declension, scholars have nevertheless gone on to categorise the various types of sentence/clause that do not hold places of declension, and have come up with a list of 7, as indicated in the table: It is important during i'rab/tarkib to mention the sentence-type which occupies or does not occupy (1) the initial sentence/clause or the sentence/clause that ensues after the resumption of speech (2) the parenthetic sentence/clause (i.e. the sentence/clause that occurs between parentheses) (3) the elaborative/elucidative sentence/clause (4) the complement to an oath sentence/clause (5) the sentence/clause occurring as a complement to a non-jazim shart or to a jazim shart but is not accompanied by the the the fa' or itha al-fuja'iyyah (6) the relative sentence/clause (7) the sentence/clause that is a tabi'ah (follower) of that which itself has no place in declension.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Nahw The Grammatical States PlaygroundDocument7 paginiNahw The Grammatical States Playgroundapi-3709915Încă nu există evaluări

- Arabic Grammar: An IntroductionDocument45 paginiArabic Grammar: An IntroductionabuhajiraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zero Arabic Grammar 2, Lower Arabic Beginner Course: Arabic Linguistic Course, #2De la EverandZero Arabic Grammar 2, Lower Arabic Beginner Course: Arabic Linguistic Course, #2Încă nu există evaluări

- Arabic Grammar For Beginners: Language of Quran with Transliteration: Arabic Grammar, #1De la EverandArabic Grammar For Beginners: Language of Quran with Transliteration: Arabic Grammar, #1Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (2)

- A Brief Summary of Qur'anic Grammar: Sarf and Nahw: Arabic Grammar, #1De la EverandA Brief Summary of Qur'anic Grammar: Sarf and Nahw: Arabic Grammar, #1Încă nu există evaluări

- Ten Lessons of Arabic Ver 2 1Document84 paginiTen Lessons of Arabic Ver 2 1asd12312350% (2)

- Understand Speak Arabic in 12 Coloured TablesDocument50 paginiUnderstand Speak Arabic in 12 Coloured Tablesabdussamad65Încă nu există evaluări

- 49 Verbs - WeakDocument3 pagini49 Verbs - WeakAl HudaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arabic Grammar Self StudyDocument13 paginiArabic Grammar Self StudyrhasnieÎncă nu există evaluări

- From Start-Up Phase Into Initial Growth: WelcomeDocument23 paginiFrom Start-Up Phase Into Initial Growth: Welcomepathanabjal12Încă nu există evaluări

- 1st Three Thulathee Mazeed by One HarfDocument5 pagini1st Three Thulathee Mazeed by One HarfAshraf ValappilÎncă nu există evaluări

- Noun cases and verb forms in Arabic grammarDocument1 paginăNoun cases and verb forms in Arabic grammarlalukhan0% (1)

- Ism Ishara: Near Plural Pair Singular Status Raf' Ma Scul Ine Nasb / Jarr Raf' Fe Mini Ne Nasb / Jarr MeaningDocument1 paginăIsm Ishara: Near Plural Pair Singular Status Raf' Ma Scul Ine Nasb / Jarr Raf' Fe Mini Ne Nasb / Jarr Meaningmasudur rahman100% (2)

- AS1722 - An Nahw Al Wadih (AMNH)Document3 paginiAS1722 - An Nahw Al Wadih (AMNH)Abdul Ghaffar50% (2)

- TaleelaatDocument7 paginiTaleelaathabiba_il786Încă nu există evaluări

- The Story of Musa Victory and Ashura FinalDocument29 paginiThe Story of Musa Victory and Ashura FinalImtiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Declinable and Indeclinable Arabic NounsDocument36 paginiDeclinable and Indeclinable Arabic Nounskoczos81Încă nu există evaluări

- Airaab Chart (اعراب)Document1 paginăAiraab Chart (اعراب)rz_bhattiÎncă nu există evaluări

- UntitledDocument15 paginiUntitledapi-56609113Încă nu există evaluări

- 001 Nahwu 19th Jan Noun BasicsDocument10 pagini001 Nahwu 19th Jan Noun Basicsdrmuhsin100% (1)

- Daftar Madinah Al-KitabDocument90 paginiDaftar Madinah Al-KitabKim Ben NajibÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arabic BasicDocument15 paginiArabic BasicAbdur RahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Khaled PDFDocument18 paginiKhaled PDFAnonymous gqriiLPÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Haaiyya Ibn Abi DawudDocument3 paginiThe Haaiyya Ibn Abi Dawudm s100% (1)

- Treasures of Arabic Morphology PDFDocument358 paginiTreasures of Arabic Morphology PDFriyaz100% (1)

- Tajweed Rules: Noon Sakin and Tanween Task Sheet Name:Amna Year: - Section: - DateDocument4 paginiTajweed Rules: Noon Sakin and Tanween Task Sheet Name:Amna Year: - Section: - Datetrickster jonasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Khulasa Tu TajweedDocument74 paginiKhulasa Tu TajweedNadeem Mahir100% (1)

- MT Arabic Vocabulary PDFDocument25 paginiMT Arabic Vocabulary PDFLeanderson SimasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Microsoft Word - The Importance of Knowing The Arabic LanguageDocument4 paginiMicrosoft Word - The Importance of Knowing The Arabic Languageapi-3800861Încă nu există evaluări

- Six Baabs TableDocument3 paginiSix Baabs TableElfaholic100% (1)

- Understand Arabic in 12 Coloured Tables (Summary)Document6 paginiUnderstand Arabic in 12 Coloured Tables (Summary)TommyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presentation On TaqleedDocument18 paginiPresentation On TaqleedAbdul Rauf ShaikhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tasheel Alnahw Ver 2.1 UpdatedDocument169 paginiTasheel Alnahw Ver 2.1 UpdatedJesús GalveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ibn Farooq's Umdatul Fiqh Lesson 1Document6 paginiIbn Farooq's Umdatul Fiqh Lesson 1Ibn Abdul KhaaliqÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Arabic Grammar A Preview PDFDocument16 paginiBasic Arabic Grammar A Preview PDFshareefgs5560Încă nu există evaluări

- Usool Ul HadithDocument73 paginiUsool Ul HadithMehjabeen Sultana100% (1)

- Arabic Ism PropertiesDocument21 paginiArabic Ism PropertiesMazin MominÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arabic 5Document2 paginiArabic 5鄺豪傑 Dr. Jacky Kwong Ho-KitÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imlaa RulesDocument15 paginiImlaa RulesHalimaalitaliyyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Major ChecklistDocument2 paginiMajor ChecklistKhateeb Ul Islam QadriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arabic NotesDocument4 paginiArabic NotesMubasher GillaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Numbers 11-20Document1 paginăNumbers 11-20api-19715112Încă nu există evaluări

- Tajweed LessonsDocument29 paginiTajweed LessonsHassiba Ghalem100% (1)

- 50 When Does The Jawab Take FADocument1 pagină50 When Does The Jawab Take FAAl HudaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arabic Grammar BookDocument80 paginiArabic Grammar BookyazadnÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lisaan Ul Quran Vol.1 - VocabularyDocument26 paginiLisaan Ul Quran Vol.1 - VocabularyNazya TajÎncă nu există evaluări

- All ArabicDocument38 paginiAll ArabicSebuta HuzaimaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mudaaf (Possessed) and Mudaaf Ilaihi (Possessor)Document6 paginiMudaaf (Possessed) and Mudaaf Ilaihi (Possessor)Bechah Kak MaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sarf The Irregular Verb AjwafDocument6 paginiSarf The Irregular Verb Ajwafapi-3709915Încă nu există evaluări

- Implications of Ibadah Akhlaq & Manner in ShariahDe la EverandImplications of Ibadah Akhlaq & Manner in ShariahÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Hidayatul-'Ibaad ila makarim aklaq dawah wal-irshad هِدايةُ العبادِ إلى مكارمِ أخْلاقِ الدَّعوةِ والإرشادِDe la Everand(Hidayatul-'Ibaad ila makarim aklaq dawah wal-irshad هِدايةُ العبادِ إلى مكارمِ أخْلاقِ الدَّعوةِ والإرشادِÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drawings and Pharmacy in Al-Zahrawi's 10th-Century Surgical TreatiseDe la EverandDrawings and Pharmacy in Al-Zahrawi's 10th-Century Surgical TreatiseÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sata TX Series QSG v1.5Document108 paginiSata TX Series QSG v1.5lucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hidayat Al Nahw ChartsDocument15 paginiHidayat Al Nahw ChartsNadia Zaheer100% (1)

- Ajrumiyya TestDocument3 paginiAjrumiyya Testapi-19708996Încă nu există evaluări

- Three Attachments On The Huruf AlDocument1 paginăThree Attachments On The Huruf AllucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Icosa Arabic Literacy ProgrammeDocument2 paginiIcosa Arabic Literacy ProgrammelucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- AjroumiyaDocument10 paginiAjroumiyaNasrin AktherÎncă nu există evaluări

- Al Ajurumiyyah EnglishDocument64 paginiAl Ajurumiyyah EnglishTanveer HussainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Three Attachments On The Huruf AlDocument1 paginăThree Attachments On The Huruf AllucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Translation in Progress Sharh Shuhur AldhahabDocument10 paginiA Translation in Progress Sharh Shuhur AldhahablucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Three Attachments On The Huruf AlDocument1 paginăThree Attachments On The Huruf AllucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Icosa Arabic Literacy ProgrammeDocument2 paginiIcosa Arabic Literacy ProgrammelucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Three Attachments On The Huruf AlDocument1 paginăThree Attachments On The Huruf AllucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Is Michael G CarterDocument2 paginiThere Is Michael G CarterlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- إعراب جدول مُحَمDocument3 paginiإعراب جدول مُحَمlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Huroofu L-Jar QuestionDocument3 paginiHuroofu L-Jar QuestionlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Huroofu L-Jar QuestionDocument3 paginiHuroofu L-Jar QuestionlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- إعراب جدول مُحَمDocument3 paginiإعراب جدول مُحَمlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Huroofu L-Jar QuestionDocument3 paginiHuroofu L-Jar QuestionlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nazm of Mughni Al LabeebDocument2 paginiNazm of Mughni Al LabeeblucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Is Michael G CarterDocument2 paginiThere Is Michael G CarterlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Is Michael G CarterDocument2 paginiThere Is Michael G CarterlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Is Michael G CarterDocument2 paginiThere Is Michael G CarterlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Is Michael G CarterDocument2 paginiThere Is Michael G CarterlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Madari Mudari Amr Declinability IndeclinabilityDocument2 paginiMadari Mudari Amr Declinability IndeclinabilitylucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- There Is Michael G CarterDocument2 paginiThere Is Michael G CarterlucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hi AllDocument1 paginăHi AlllucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading and Writing in Arabic On Windows PCsDocument5 paginiReading and Writing in Arabic On Windows PCslucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- Three Attachments On The Huruf AlDocument1 paginăThree Attachments On The Huruf AllucianocomÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Practical Foundation For I Rab and TarkibDocument6 paginiA Practical Foundation For I Rab and Tarkiblucianocom100% (1)

- TKT Module 2 Selection and Use of Coursebook Materials PDFDocument7 paginiTKT Module 2 Selection and Use of Coursebook Materials PDFRachel Maria RibeiroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jim CumminsDocument2 paginiJim CumminsErica Mae VistaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan English Sekolah Amanah 2Document3 paginiLesson Plan English Sekolah Amanah 2Yunus RazaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grammar NotesDocument5 paginiGrammar NotesNana ZainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lec - PragmaticaDocument27 paginiLec - PragmaticaAdrian Savastita100% (1)

- Turkish LanguageDocument23 paginiTurkish LanguageThe Overlord GirlÎncă nu există evaluări

- Present Perfect Tense PoemDocument5 paginiPresent Perfect Tense PoemJ JÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan LanguagesDocument4 paginiLesson Plan Languagesapi-253749086100% (1)

- Test PaperDocument3 paginiTest PaperGanesh KaleÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2-Process of CommunicationDocument15 pagini2-Process of CommunicationCARRIE ANN BANALÎncă nu există evaluări

- COMPREHENSION PASSAGES Class 7Document4 paginiCOMPREHENSION PASSAGES Class 7ayan5913Încă nu există evaluări

- ĐỀ WRITING NĂM 2 - HKI I 2021 2022 1Document4 paginiĐỀ WRITING NĂM 2 - HKI I 2021 2022 1Hà Nguyễn Thị ThuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Answers Key-Eng7 Q2Document1 paginăAnswers Key-Eng7 Q2guia bullecerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Philippine EGRA - As of Sept 11 Imus VersionDocument13 paginiPhilippine EGRA - As of Sept 11 Imus VersionJee RafaelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Present Progressive RulesDocument2 paginiPresent Progressive RulesJuan RoaÎncă nu există evaluări

- English: Whole Brain Learning System Outcome-Based EducationDocument20 paginiEnglish: Whole Brain Learning System Outcome-Based EducationTrinidad, Gwen StefaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- OMANI ARABIC RESOURCESDocument2 paginiOMANI ARABIC RESOURCESdln2510Încă nu există evaluări

- Grade 2 Worksheets PDFDocument3 paginiGrade 2 Worksheets PDFMarios25% (4)

- Grammar Mastery Matrix TrackingDocument2 paginiGrammar Mastery Matrix TrackingSamori CamaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- CEP Lesson Plan: Review or Preview (If Applicable)Document3 paginiCEP Lesson Plan: Review or Preview (If Applicable)api-278743989Încă nu există evaluări

- Volune-6 - Issue-1-2012Document256 paginiVolune-6 - Issue-1-2012Trung NguyenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparative vs. SuperlativeDocument14 paginiComparative vs. SuperlativeJHONJIMMY CASTANEDARENDONÎncă nu există evaluări

- Grammar Exercises Book 5Document134 paginiGrammar Exercises Book 5DAVID LEONARDO ROJAS OROZCOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ujian Akhir Semester Genap Tahun Akademik: 2016/2017: 4. He Was Sleeping When You.... Him Last NightDocument9 paginiUjian Akhir Semester Genap Tahun Akademik: 2016/2017: 4. He Was Sleeping When You.... Him Last NightAndi Auliyah WarsyidahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Detailed Lesson Plan in MTB MLEDocument6 paginiDetailed Lesson Plan in MTB MLECristina LaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adverb Phrases - English Grammar Today - Cambridge DictionaryDocument3 paginiAdverb Phrases - English Grammar Today - Cambridge DictionaryKoniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Common Speech Recognition CommandsDocument9 paginiCommon Speech Recognition Commands2023.copabhavanapawarÎncă nu există evaluări

- PT-2 English Class VIIDocument3 paginiPT-2 English Class VIIMyth White WolfÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enhanced English 4: Quarter 1 - LAS WEEK 3Document6 paginiEnhanced English 4: Quarter 1 - LAS WEEK 3JUN RILL GURREAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Semiosis and Intersemiotic Translation - Mouton-LibreDocument10 paginiSemiosis and Intersemiotic Translation - Mouton-LibreIsadora RodriguesÎncă nu există evaluări