Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Dinosaurs

Încărcat de

KennethDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Dinosaurs

Încărcat de

KennethDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Contents

Out of the Past . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Since the World Began . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

How We Find Out . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

The Age of Reptiles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

The Ruling Reptiles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Giant Plant Eaters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Lightweights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Giant Meat Eaters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Plated Dinosaurs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Armored Dinosaurs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Duckbills, Boneheads, and Parrot Beaks . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Horned Dinosaurs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Flying Reptiles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Marine Reptiles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Early Birds and Mammals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

The End of the Line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

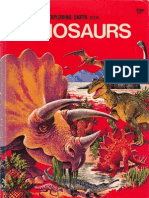

A GOLDEN EXP LORING EARTH BOOK

DINOSAURS

Dinosaurs-those "terrible lizards" of the past-

illustrated in full color; mammoth plant eaters,

terrifying meat eaters, strange duckbilled

and armored giants, flying reptiles, and

huge creatures from ancient seas;

fascinating facts about these and

many more

GOLDEN PRESS

.

By

Alice Fitch Martin and

Bertha Morris Parker

Illustrated by

Hamilton Greene,

Robert Korta,

Rudolph F. Zallinger

and others

Cover by

Rod .uth

Western Publishing Company, Inc. Racine, Wisconsin

Copyright 1973 by Western Publishing Company, Inc. Illustrations on pages 22, 36, and 46

from CREATURES OF THE PAST 1965 by Harper & Row. All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Printed in U.S.A.

GOLDEN PRESS@, GOLDEN, and A GOLDEN EXPLORING EARTH BOOK are trademarks

of Western Publishing Company, Inc.

/

When such a l i fe-size restoration i s

el ectronical l y ani mated, the creature

seems al most as real as the ani mal s

we see at the zoo.

Out of the Past

No one has ever seen a dinosaur, and

no one ever will. The dinosaurs were

long gone from the earth by the time man

appeared. Our mammal forerunners of

dinosaur days were hairy little creatures

that probably spent most of their lives

just grubbing for food and trying to keep

out from under the dinosaurs.

The name dinosaur comes from two

Greek words meaning "terrible" and

"lizard." Actually, the dinosaurs were not

lizards, although, like the lizards, they

were reptiles; and many of them were not

terrible at all. They were given the name

because some of the frst ones scientists

found out about were huge and power

ful meat eaters.

In their time, the dinosaurs were nu

merous and widespread, and there were

many diferent kinds. Some were big,

some little. There were tall ones, short

ones, long ones, and fat ones. Some walked

on two legs, some on four. There were

dinosaurs with horns, dinosaurs with

webbed feet, and dinosaurs with heavy

coats of armor. There were toothless dino

saurs and dinosaurs with so many teeth

that you could count them by the hundred.

Hooves, claws, spikes, topknots, and ruf

like collars of bone are among the great

variety of things that ftted diferent kinds

of dinosaurs for their particular ways of

life. One thing, however, all dinosaurs

had in common: They had legs that lifed

their bodies up of the ground so that

they could run or leap or stomp about.

During most of their stay on earth, the

dinosaurs were the undisputed rulers of

the land. Their reign-the longest in the

history of the earth-lasted for more than

10 million years. What ended it is a

myster.

As recently as about a hundred years

ago, no one even guessed that there had

ever been such animals as dinosaurs.

Today their name is a household word.

We have toy dinosaurs and books and

games and puzzles about dinosaurs. There

are dinosaur cartoon characters in the

movies and in comic strips. We can go to

museums and see mounted skeletons of

dinosaurs. Some parks and museums have

life-size restorations we can look at and

wonder at. The picture shows such a res

toration of Stegosaurus, one of the so

called plated dinosaurs.

3

Since the Worl d Began

Even as long ago as the days of dino

saurs, the earth was old. It had been

wheeling around and around the sun,

spinning as it went, for billions of years

before there were dinosaurs. In the be

ginning, there were no living things at all.

The chart below tells a little of the

story of the earth, from its birh some 5

billion years ago down to the present.

Most of it stands for a long stretch of

time about which we know very little.

The part of earth history we know most

about is the part included in the narrow

bands at the far right-the bands that

cover the 600 million years of the Paleo

zoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic eras.

The Mesozoic, which lasted 165 million

years, is ofen called the Age of Reptiles.

It was through much of this time that the

dinosaurs ruled the earth. Our own era,

birth of

Earth-

4. bil l ion

years ago

the Cenozoic, began only 65 million years

ago. To show, on the same scale, the time

man has existed would call for a division

at the right too fne to see without a mag

nifying glass.

Scientists cannot say just how the earth

began. One idea that seems to be bore

out by Apollo moon fndings is that the

earth was formed by the banging and

sticking together of bodies like our moon

as they whirled around .the sun. Even

tually, heat built up deep inside the young

earth, and the rocky core tured molten.

Volcanoes spewed out lava.

The early atmosphere was a mixture

of ammonia and other poisonous gases.

In it foated a dense canopy of clouds,

formed from water vapor escaping from

the rocks. Rains poured down and grad

ually formed the ocean. There life began.

oldest known

rocks-formed

. bill ion

years ago

earl y

living

things

chlorophyll

appeared in plant

cel l s Z. bil l ion

years ago

The time when that frst living thing ca

pable of producing others like itself ap

peared was over three billion years ago

probably sometime between the earth's

one-billionth and two-billionth birthdays.

The next great event in the story of the

earth was the development of the green

pigment chlorophyll. With chlorophyll,

living cells could use the energy of sun

light to make food for themselves out of

chemicals in the sea. In the process, they

added oxygen to the air.

With a better supply of food and grow

ing amounts of oxygen, life could develop

at a faster rate. By the beginning of the

Paleozoic, all the big groups of animals

now in existence-except the backboned

group, the one to which we ourselves

belong-had appeared.

simple plants and animals

Throughout the frst half of"the Paleo

zoic, the leading animals were all inver

tebrates-the animals without backbones.

Chief among them were trilobites. The

time is called the Age of Invertebrates.

During it, fshes, the frst backboned ani

mals, made their appearance. They quickly

became so numerous that the middle pe

riod of the Paleozoic is called the Age

of Fishes.

The Age of Fishes was followed by the

Coal Age. The Coal Age could just as well

be called the Age of Amphibians, for am

phibians were the leading animals. From

them the reptiles sprang. By the time the

Paleozoic ended, the reptiles had pushed

the amphibians aside. This is the time when

the dinosaurs appeared and became the

rulers of the earth.

.

_

o E

. E

(0

<

How We Fi nd Out

The last dinosaurs died more than 60

million years before there were any people

on the earth. Of course, then, no written

records have come down to us from dino

saur days to tell us about these fantastic

creatures. However, we know much about

them and other living things of long ago,

because scientists have learned to "read

stories" in rocks.

All the traces found in rocks of the

living things of past ages are called fossils.

Shells, teeth, and bones are common fos

sils. The very frst dinosaur fossils found

were teeth.

The men in the picture below are digging

out the bones of a dinosaur. The bones

are petrifed. Petrifed means "turned to

stone." The bones were petrifed in this

way: When the dinosaur died, it sank to

the bottom of a pond. In time, its body

was covered with mud. The soft parts

rotted away, leaving only the bones. Little

by little, minerals from the water flled up

every tiny space in the bones. Then the

water took away, bit by bit, the bone ma

terial itself, leaving minerals in its place.

At last the bone was all stone, and the

layer of mud around it had turned to a

layer of solid rock.

By far the greatest number of fossils are

found in regions where many layers of

water-made rock are piled one on top

of another. Each layer is likely to be a

chapter in the story of the living things

of past ages. It is easy to understand that,

if the layers of rock in a region have not

been disturbed, the oldest rocks are at the

bottom, the newest on the top.

No one could count on having much

success as a fossil hunter if he went out

to the middle of a feld and dug down to

the layers of rock below. Fossil hunting

is easiest where streams have done some

of the digging needed. On steep valley

slopes, a fossil hunter cannot depend on

looking at a rock layer and seeing what

fossils are to be had for the digging, but

ofen a shell or the end of a bone may

stick out and show that there are fossils

to be had.

Signs of fossils are easier to sight in

arid regions, where the ground is almost

bare, than in regions of grass and trees.

The badlands in the western part of the

United States and Canada, for example,

have given up great numbers of dinosaur

bones and other fossils.

Also numerous in many fossil beds are

dinosaur footprints. The boy pictured is

resting his feet i the footprint of a huge

dinosaur. The footprint is more than a

yard long. Picture a giant dinosaur lum

bering along the muddy bank of a pond

some 150 million years ago. Since the

creature weighed many tons, its feet made

deep footprints in the sof mud. By chance,

this footprint was not disturbed. As cen

tury afer century went by, the mud

changed to solid rock. How amazed the

little boy would be if the monster that

made the print should suddenly appear!

Perhaps you have made a plaster cast

by pouring wet plaster into a mold and

letting it harden. Some dinosaur fossils

are casts of dinosaur footprints. Suppose

a small dinosaur lef a footprint in a mud

dy bank. Later, while the footprint was

clear and sharp, a thick layer of sand was

washed up over the mud. It flled in the

footprint and covered the ground all

around it. In time, both the mud and the

sand were cemented into solid rock. When,

long aferward, the layer of sandstone and

the layer of mudstone were split apart, the

imprint of the dinosaur's foot still showed

in the mudstone, and, rising up from the

sandstone, there was a cast of the foot.

di nosaur l eg bone

dinosaur

skeleton

di nosaur cast

footpri nts

For years afer the frst fossils of dino

saurs were discovered, scientists could only

guess that dinosaurs, like most reptiles,

laid eggs. Then some petrifed eggs were

found alongside skeletons of the dinosaurs

that laid them. Though others have since

tured up, eggs are not common fossils.

Locating a fossil is ofen only a small

part of getting it. If a hunter has found,

for instance, the bones of a giant dino

saur, he has ahead of him the long, hard

task of digging them out of the rock they

are in. He may need shovels, hammers,

picks, or even dynamite to loosen them.

A big bone may have

y

been broken at some

time during the ages, and getting it out

8

of the rock may mean getting out many

small pieces, perhaps hundreds. The fos

sil hunter may have to use pieces of wood

and iron and even bandages to hold the

parts of a broken bone together. If the

bone is not too large, he may cover it all

with plaster.

Large fossils may be so heavy that they

are hard to handle. The petrifed skull of

one great dinosaur, when packed and

ready to be shipped to d museum work

shop, weighed over 3, 500 pounds!

Building the fossil bones of an ancient

animal into a skeleton may take months

of work. Bits of rock remaining on the

bones must be chipped away, and then

the bones must be sorted according to

where they belong and fastened in place.

A framework of metal tubing, or "plumb

ing," supports the skeleton.

If the animal is one that is new to

scientists, there is always the question of

whether all its bones are there. An artist

who drew pictures of giant dinosaurs when

only a few had been discovered always

showed the dinosaurs coming out of a

pond or group of trees, so that the end

of the tail did not show, in case some

tailbones might be missing.

From the skeleton of an ancient ani

mal a great deal can be told about the

animal-its size, how it moved about,

whether it ate plants or meat, how big

its brain was, and what animals of today

it was most like. Knowing how today's

animals are built and how and where they

live helps scientists to know about the

animals of long ago.

The stor of the living things of past

ages still has many gaps in it, but there

is always a chance a fossil will turn up

that will fll one of those gaps. Not many

years ago, a fossil hunter found the bones

of a duck-billed dinosaur in Mexico, near

the Pacifc coast. Until then, no trace of

that kind of dinosaur had ever been

found so far west in North America. You

yourself may someday add something to

the story of dinosaurs.

Oviraptor

Stegosaurus

The Age of Reptiles

It is easy to see from the chart how

the Mesozoic Era earned the name of Age

of Reptiles. From early reptilian begin

nings back in the Coal Age, there had

arisen, by. the time the curtain went up

on the Mesozoic, six major groups of

reptiles, all of them destined for stardom.

Each of the six groups is shown in a dif

ferent color on the chart. It was in the

Triassic, the frst act of the great reptile

show, that the dinosaurs made their bow.

As the chart shows, there were two

separate lines of dinosaurs. The two were

about as closely related as horses and

cows. Their common ancestor, the theco

donts, also gave rise to the pterosaurs, or

fying reptiles, and to the crocodilians.

Birds, too, descended from the theco

donts, but, through the ages, the birds be

came so diferent from their reptile rel

atives that they are put in a class by

themselves.

In the second and third acts-the Ju

rassic and Cretaceous periods-the reptiles

were at their peak. Dinosaurs ruled the

land. Other reptiles ruled the seas. In the

air, the pterosaurs were, for the most part,

without serious rivals. By the beginning

of the Cretaceous, only one group, the

mamm

a

llike reptiles, had already l eft

the stage. Before it did, however, it had

given rise to still another big class of ani

mals-the mammals.

When the curtain went down on the

Mesozoic, it went down on the dinosaurs

and most of the other reptiles that had

shared the limelight with them. Of the

reptiles that are lef alive today, most play

minor roles.

Strangely enough, it was an egg that

stared the Age of Reptiles. The eggs of

10

c

D

w

L

0

0

w

c

D

m

.

D

i O

-

l

L

O

w

=

D

O

c

a O

O

> c

Il

C

0

D

O

:

L

=

+ Living Reptiles -

olgolors ond

crocodes

Thecodonts

ancestors of

the dinosaurs

Lynognolhus

the fshes and the amphibians are laid in

water, to keep the eggs from dring out,

and the baby animals that hatch from

them are water animals. The egg of a

reptile is a land egg .. It is a private hatch

er pool for the little reptile growing in

side it. Because of such eggs, the reptiles

were free to exploit the land.

Like the fshes and amphibians, the

reptiles are cold-blooded. They cannot

regulate their body temperature the way

the warm-blooded birds and mammals

North

America ,

,

Europe

and

Asia

eq;to,------ ------------

South

America

Africa

Madagascar

0

'(

o''

o

1\"'t

Antarctica

do. Instead, their bodies are the same

temperature as the air or water around

them. Today, only small reptiles live where

the winters are ver cold. Yet fossils from

far northern lands, among them the island

of Spitsbergen, tell that large dinosaurs

once lived there. Others, from Antarctica,

reveal that good-sized reptiles used to

live on that now-frozen continent at the

bottom of the world.

Clearly the climate in these widely

separated regions of the earth was milder

North

America

Europe

and

Asia

equato;------

-

---------

North

America

South

America

Africa

Europe

and

Asia

Antarctica

South

America

Africa

/Madagascar

o

\tl

Antarctica

North

America

Europe

and

Asia

-equal----------------

South

Africa

America

Antarctica

than it is now. It is not surprising, then,

that in that balmier time the dinosaurs

were wdespread.

But how had dinosaurs, which are land

animals, managed to travel between re

gions separated by hundreds-in some

cases thousands-of miles of sea? Dino

saur fossils like some found in Europe,

for instance, tum up in rock layers of

Australia and Madagascar, both remote

from all other land.

Some geologists have said that, in such

cases, the animals must have crossed the

sea on land bridges no longer in existence

or by island hopping-going from island

to island, that is, and so covering long

stretches in short stages. Others have ar

gued that the animals might have been

able to swim long distances.

Many scientists, however, have for years

had the idea that the answer lies in the

location of the continents. They say that

the continents were not always spread out

over the globe as they are now but, in

stead, over millions of years, drifed to

their present, separated positions. At the

start of the Mesozoic, these scientists say,

all the lands of the earth were clumped to

gether in one huge supercontinent they call

Pangaea.

The maps show how they think the

continents came to be where they are now.

In the Triassic, the supercontinent began

to split apart. North America and Eurasia

formed one large northern continent :

Laurasia; and the four southern continents,

together with India, formed a southern

one: Gondwana. The Jurassic saw Ant

arctica separate from Africa and South

America, and India start drifing north

ward. By Cenozoic time, both South Amer

ica and Madagascar had broken away

from Africa, but it was not until well into

the Cenozoic that North America and

Greenland parted completely from Eu

rope, India jammed into Asia, and Austra

lia separated from Antarctica.

Studies made of the ocean foors bear

out the idea of continental drift. So does

evidence, found in the rocks, of apparent

wanderings of the earth's north magnetic

pole. So, too, do such fossil fnds as those

of the mammal-like reptile Lystrosaurus,

with its plant and animal neighbors, in

rock layers in Antarctica;_ these layers are

of the same age as those containing sim

ilar fossils in South Africa. Today most

scientists agree with the idea of conti

nental drift.

1 3

The Rul i ng Repti l es

Sal toposuchus

You have already seen, on pages 10

and 1 1, that two of the branches on the

big center limb of the tree diagram rep

resent the dinosaurs, and the other two

branches, the fying reptiles and the croco

dilians. These four groups, together wit

the thecodonts from which they came,

are known as the archosaurs, or ruling

reptiles. The name comes from archos, a

Greek word meaning "ruler. "

Saltoposuchus is one of the best known

of the thecodonts. This early ruling rep

tile is often spoken of as the grandfather

of the dinosaurs. Like many of its famous

dinosaur descendants, Saltoposuchus ran

or leaped about on two long, strong hind

legs, its muscular tail streaming out be

hind. The long, heavy tail balanced the

forward tilt of the animal's body.

Looking at Saltoposuchus as it darted

about in search of a small lizard or drag

onfy to get -its teeth into, you probably

wouldn't have dreamed that it would one

day have "grandchildren" the length of a

locomotive and the weight of more than

half a dozen elephants. Saltoposuchus

was about the size of an undernourished,

unfeathered turkey gobbler.

14

The most specialized of the thecodont

descendants-except, of course, for the

birds-were the pterosaurs. This group

developed wings-wings quite diferent

from those of birds-and took to the air.

The pterosaurs may even have been some

what warm-blooded.

The least specialized were the croco

dilians, though a few, in the course of

time, developed special adaptations for

life in the sea .. Some crocodiles of today,

too, can live in salt water. The croco

dilians are the only ruling reptiles that

survived the "time of the great dying" at

the close of the Mesozoic.

Of ruling reptiles, the superstars, of

course, are the dinosaurs. The creatures

are fascinating partly because of the enor

mous size many of them reached and

partly because they dominated the earth

for so long and then disappeared com

pletely. Why these animals lived so long

and

.

then disappeared is a question scien

tists have never been able to answer.

The "X-ray" views of the hip joints of

the dinosaurs in the pictures show the

chief distinction between the members of

the two big dinosaur groups. The lizard

hip dinosaur group (Saurischians), repre

sented here by Gorgosaurus and Cam

arasaurus, is the one to which most of the

dinosaurs we think of as typical belong

the giant plant eaters and meat eaters.

All the meat-eating, or carnivorous, dino

saurs belong here. The bird-hip dinosaurs

(Orithischians), represented in the pic

tures by Camptosaurus and Stegosaurus,

were 100 percent plant-eating, or herbiv

orous. Both groups included dinosaurs

that walked on four legs and those that

walked on two.

For nearly 1b mi l l ion years, these four groups

otrepti les ruled the earth. Of these, only the

crocodi lians survived. Shown above i s an al l igator,

a li" vi ng relative of thi s anci ent group.

Gorgosaurus

Camptosaurus

Stegosaurus

Crocodilians

Al l igator

Pterosaurs (fying reptiles)

Lizard-Hip Dinosaurs

Camarasaurus

Bird-Hip Dinosaurs

Brachiosaurus

16

Giant Pl ant Eaters

This picture introduces you to the giant

of giants, Brachiosaurus, the biggest ani

mal, so far as scientists have found, that

ever walked the earth. The only bigger

animals known-today's giant whales

live in the sea. Brachiosaurus, however,

with a weight of 50 tons and a length of

80 feet, approached half the weight of the

biggest whale-the big blue whale, or sul

phur-bottom-and measured almost as

long. In height, Brachiosaurus outranks

all other animals, past and present. With

its head held high it stood over 40 feet

tall. The big reptile could easily have

looked over the top of a three-story build-

Plateosaurus

ing-supposing there were such a building

150 million years

a

go.

The name Brachiosaurus means "arm

lizard. " The name comes from the fact

that this dinosaur did not follow the usual

dinosaur pattern of having front legs short

er than the hind legs.

Although Brachiosaurus would certainly

have been frightening to meet, it was not

one of the dinosaurs that earned for them

the name "terrible lizard. " Brachiosaurus

was a slow-moving, harmless creature that

ate nothing but plants. It was also slow

witted. In spite of it

s

enormous size, the

big plant eater had a brain smaller than

a kitten's. In proportion to its weight,

Brachiosaurus got by with fewer ounces

of brain than any other back boned animal

we know about.

The group of giant plant eaters to which

Brachiosaurus belonged are ofen called

the amphibious dinosaurs, because most

scientists think they spent much of the

time in swamps and ponds, where the

water helped to hold up their heavy bodies.

Even though their legs were like tree

trunks, the great weight of these dinosaurs

must have been a tremendous burden.

Yal eosaurus

Brachiosaurus, with its long neck and long

front legs, could stand in deep water and

still have its head out of water. Actually,

it needed only the top of its head clear

of the water, for its nostrils were located

in a bony crest at the top.

Brachiosaurus and its fellow waders had

teeth suitable for eating soft plant food.

They must have spent most of their days

cropping water plants, for their enormous

bodies needed tremendous amounts of

food. Clearly the creatures were well ft

ted for such a life, for they survived, in

one part of the world or another, for 100

million years! Fossils of Brachiosaurus

have been found in such widely separated

areas as North America, Europe, and Af

rica. Skeletal remains thought to be its

bones have been found in Asia, too.

Yaleosaurus and Plateosaurus were

forerunners of Brachiosaurus and the

other giant plant eaters. They were not

nearly as large as those later giants, but

they certainly were not small. Plateosaurus

was about 20 feet long, Yaleosaurus about

8 feet.

Both of these early dinosaurs could

walk on just their hind legs as well as on

17

Camarasaurus

all fours. Probably they stayed on all fours,

except when they were in a hurry. Their

teeth were ftted for eating plant food

rather than meat.

In the picture, Y aleosaurus is brown

and Plateosaurus green. Y aleosaurus has

stripes across its back, while Plateosaurus

has a mixture of stripes and splotches.

Actually, no one kno

w

s what color either

these or any other dinosaurs were or what

markings they had. Artists can only guess,

from the color and markings of modem

reptiles. Common reptile colors today are

brown and green. Markings, moreover,

help today's reptile to hide from meat

eating enemies. It is a good guess that

these two dinosaurs were ofen hunted by

meat eaters of the time and that they had

1 8

markings of one kind or another that

helped to conceal them among the shad

ows and plants.

Just as Brachiosaurus was the giant of

the amphibious dinosaurs, Camarasaurus

was the pygmy. It was only about a third

as long as Brachiosaurus. Even so, it

weighed many tons and followed the same

general body patter-that is, a big body,

a long neck and tail, and a small head

with a tiny brain inside. The skull of

Camarasaurus has been compared with

that of a bulldog. It was short, and the

jaws were heavy. The teeth in the big

plant eater's jaws, however, were not

much like a bulldog' s.

Diplodocus, another record holder, was

the longest of the amphibious dinosaurs.

From the tip of its jaws to the end of its

tail, Diplodocus measured nearly 100

feet-one-third the length of a football

feld or, put in another way, the length

of seven or eight elephants marching trunk

to tail. Imagine Diplodocus in such a

parade!

Diplodocus was far more slender than

big Brachiosaurus. It weighed a mere 25

tons, give or take 5 tons.

The name Diplodocus means "double

beam. " The dinosaur was given the name

because it reminded scientists of a kind

of scale for weighing-a balance with

beams. Its ver long neck just about bal

anced its very long tail.

On its feet Diplodocus had broad pads,

much like those of an elephant. Some of

the toes were clawed. Probably they kept

it from sliding around in the mud. All

Dipl odocus

the amphibious dinosaurs had feet very

much like those of Diplodocus.

Like Brachiosaurus and the other giant

plant eaters, Diplodocus had only a tiny

brain. Along the spinal cord, however,

these dinosaurs had knots of nerve cells,

called ganglia, that controlled the legs and

tail. When we wish to move any part of

our body, a message must go along nerves

to the muscles in that part of the body.

Suppose, as you are washing your hands

under the faucet, the water suddenly gets

too hot for comfort. A pain message travels

along nerves from your hands to your

brain. Then a message goes back from

your brain to the muscles of your hands,

and you pull your hands away. It all hap

pens almost as quick as a wink, because

the messages to and from your brain have

only a short distance to travel.

Suppose, however, an enemy grabbed

Diplodocus by the end of its long tail.

It would take a large part of a minute

for the danger message to go the 90 feet

or so to the dinosaur's brain and for the

return message to tell the muscles to lash

the tail at the enemy. In that time, the

end of the tail might be gone. Having a

"helper brain" (ganglion) closer to the

tail and legs was certainly an advantage.

19

Diplodocus and Camarasaurus may

ofen have come face-to-face with Brach

iosaurus, for they, too, were common in

what is now North America. Another

giant whose bones are found with theirs

is Brontosaurus, the best known of all the

big plant eaters and one of the frst to be

discovered. Brontosaurus, as you can see,

looked much like Camarasaurus, but

Brontosaurus was over twice the length

of Camarasaurus and weighed many tons

more. However, it lacked some 15 feet

of being as long as Diplodocus and some

15 or 20 tons of being as heavy as the

giant Brachiosaurus.

The name Brontosaurus means "thunder

lizard. " The scientists who frst found and

20

put together the bones of its skeleton

thought that when so big a creature walked

about, the ground shaking underfoot must

have rumbled like thunder. The big foot

print pictured on page 6 records one of

its thunderous footsteps. It is easy to see

that the great dinosaur would have crushed

any small animal it stepped on. As with

all the giant plant eaters, Brontosaurus,

aside from sheer bulk, had no weapons

other than its long tail for protection

against enemies. The whiplash from such

Brachiosaurus

Di pl odocus

I

a tail, however, would really be something

to watch out for.

Some of the reptiles of today are long

lived. The giant tortoise, in fact, holds

the record for long life among animals.

It may live to be 150 years old. Scientists

cannot tell how long dinosaurs lived. Some

say that Brontosaurus may have lived to

be 1,000 years old. Others believe that

200, or at most 300, years is a better

guess. Still others say less than 100.

It would be easier for scientists to get

an idea of how fast the big dinosaurs grew

and how old they lived to be if there were

fossils of newly hatched and young and

middle-aged

pecimens. Almost all the

skeletons of the giant plant eaters, unfor-

Brontosaurus

tunately, are of adult forms. It would seem

that these huge dinosaurs, unless a whole

community of them were wiped out and

buried in some natural catastrophe, ordi

narily were either eaten up by enemies

when young or lived to adult size.

The giant plant eaters you have just

read about were all lizard-hips. For mil

lions of years these giants had the swamps

and lakelands of the Mesozoic pretty

much to themselves. In time, however,

they were largely replaced, at least in the

northern continents, by big plant-eating

dinosaurs of the bird-hip group. But nei

ther those later dinosaurs nor any other

land animals we know about have come

close to matching them in size.

Podokesaurus

Lighteights

Afer reading about such giant dino

saurs as Brontosaurus and Diplodocus,

you may be shocked to learn that the

four small reptiles pictured on these two

pages are also dinosaurs. They were all

far from gigantic. These slim, long-legged

dinosaurs represent a group often spoken

of as "lightweights. "

Like the giant plant eaters, the light

weights were lizard-hip dinosaurs. But

these small lizard-hips walked or ran on

their hind legs. That is, they were bipedal.

Their front legs and feet served as arms

and hands. In the main, they were meat

eaters, and their long legs suggest they

could move fast, as meat eaters ofen have

to do to catch the food they need.

Podokesaurus, the "swif-footed lizard, "

was an early dinosaur. Its gigantic cous

ins would not appear for many millions

of years. However, another forerunner of

the giants, 20-foot-long Plateosaurus, and

other dinosaurs much like it, were already

present. They certainly dwarfed speedy

little Podokesaurus, which was less than

a yard long. Of course, so small a meat

22

eater was hardly a threat to creatures the

size of Plateosaurus. Probably it ate most

ly little lizardlike reptiles.

Compsognathus lived several million

years afer Podokesaurus, during the great

days of Brontosaurus and its fellows. No

Compsognathus

bigger than a rooster, it was even smaller

than Podokesaurus. It probably ate other

small reptiles, j ust as Podokesaurus did,

but it had a more varied diet; by this time

there was a good supply of small furry

animals-mammals-scurrying about.

Among still later lightweights were

those known as ostrichlike dinosaurs.

Oviraptor and Ornithomimus were two of

them. Ornithomimus means "bird mimic. "

Another name for the same dinosaur is

Struthiomimus-"ostrich mimic. " Ovi

raptor's name means "egg robber. " This

dinosaur was only about a yard long.

Ornithomimus measured about 8 feet.

With their long necks and legs and

their small heads, these dinosaurs did in

deed look much like ostriches. Like os

triches, too, they had horny bills and no

teeth. Of course, they difered greatly

from ostriches in having long tails and

not having feathers. Moreover, they had

arms and hands instead of wings.

It seems strange for meat eaters to be

toothless. The answer, scientists think, is

that these members of a meat-eating line

had probably become chiefy egg eaters.

They could handle the eggs easily with

their hands. They could peck holes in the

shells with their bills. They did not need

teeth for chewing the contents of the eggs.

There were insects they could eat, too.

Sometimes, apparently, these egg steal

ers were caught in the act. In one of the

nests of petrifed dinosaur eggs, scientists

also found the crushed skull of a supposed

egg-stealing dinosaur.

Ornithomi mus

Ovi raptor

As you may remember from the reptile

tree on page 11, the lightweights are on

the same branch of lizard-hips as the

giant meat eaters. Those big brothers of

theirs, which stalked the land through

much of the Age of Reptiles, were the

truly terrible dinosaurs.

23

Allosaurus

Giant Meat Eaters

The living things of every natural re

gion of the world can be thought of as a

pyramid. At the base of the pyramid are

green plants. Without green plants, there

could not be any animals, because the

food of all animals can be traced back

to green plants. Above the green plants

are the plant-eating animals-some big,

some small. Another name for them is

herbivor

s. Above the plant eaters are the

meat eaters-the carnivores. Again, some

are big and some are small. The biggest

and fercest of the meat eaters of a region

is known as the top carnivore.

In a large part of Mrica today, the top

carnivore is the lion. It feeds on zebras,

girafes, and antelopes, all of which eat

grass and other green plants.

In the days of the dinosaurs, the liv

ing things of the diferent regions formed

24

similar pyramids. The plants were not the

same as those of today, but they furnished

food for the plant eaters, just as modern

plants do. Among the leading plant eaters

on land were such giant dinosaurs as

Camarasaurus, Brontosaurus, Diplodocus,

and Brachiosaurus. The leading carnivores

were huge meat-eating dinosaurs. No one

would question the choice of the name

dinosaur for these reptiles. They were

truly terrible.

Allosaurus, the "leaping lizard, " pic

tured here feasting on some big reptile

it has killed, was one of those giant meat

eaters. These huge and terrible dinosaurs

belong to the same big dinosaur group,

the lizard-hips, as the giant plant-eating

dinosaurs.

Allosaurus's victim in the picture could

well have been Brontosaurus. Bones of

the thunder lizard that show the marks

of Allosaurus's teeth have been found.

Think of having 30 tons of fresh meat

from a single kill! To eat it all, Allosaurus

would have had to go back time afer time

to feed.

Allosaurus was not as big as most of

the giant plant eaters it preyed on. Even

so, it stood some 15 feet tall as it stalked

or leaped about on its strong hind legs.

The ponderous plant eaters had no chance

of escaping Allosaurus by running away.

They weren't fast enough. Perhaps only by

moving into deep water were they safe

from its claws and teeth.

The front legs of Allosaurus were much

smaller than the hind legs. They were

of no use in walking, but the three "fn

gers" on each "hand" were armed with

long, sharp claws. The hind feet, too,

were clawed. They were much like the

feet of a giant bird.

Allosaurus clearly did not follow the

small-head pattern of the giant plant eat

ers. Its skull was 2l feet long. Its mouth,

like the mouths of today's snakes, opened

very wide, so the creature could swallow

great chunks of food. As you know, the

plant eaters had teeth that could chew

only sof plants. In contrast, the teeth of

Allosaurus were long and strong and as

sharp as knives. They were a great help

in killing prey and stripping the meat

of the bones.

Besides the giant plant eaters, there

were plenty of smaller dinosaurs and other

reptiles to furnish meals for Allosaurus

and its meat-eating relatives. We can

guess that giant plant eaters were ofen

saved, for the time being, by the presence

25

Skul l and head of Tyrannosaurus

of some smaller prey that could be cap

tured without a battle. Of course, the bat

tles between Allosaurus and the big plant

eaters we can only imagine. We know

about these fghts only from such signs

found in the rocks as broken bones and

missing teeth.

If you knew about all the big animals

of the past an

d

could choose the one you

would least like to meet today, the one

you would probably choose is the dino

saur Tyrannosaurus, the "tyrant lizard. "

This dinosaur is believed to be the largest

carnivore that ever walked the earth. It

was probably the fercest, as well. Just

imagine a huge, man-eating reptile, four

times as tall

.

as you, coming toward you

on its hind legs, eyes glaring and jaws

agape and all its big, evil-looking teeth

showing clearly, and you will have some

idea of what Tyrannosaurus must have

been like.

26

The whole name of this most terrible

of terrible reptiles is Tyrannosaurus rex.

The rex in the name means "king. " The

huge meat eater was "king of beasts"

100 million years ago, just as the lion is

said to be today.

Tyrannosaurus lived at a later time

than Allosaurus. It lived in the Cretaceous

period, while Allosaurus had its heyday

in the Jurassic. The family of Cretaceous

dinosaurs to which Tyrannosaurus be

longed are ofen called deinodonts. The

word means "terrible teeth. " Gorgosaurus,

one of the dinosaurs pictured on page 15,

was a member of the family. The name

deinodont, in fact, comes from one of

the many names that Gorgosaurus has

been given by scientists.

Tyrannosaurus was much larger than

Allosaurus. Its body measured nearly 50

feet from the top of its head to the tip

of its tail. Allosaurus was only 35 feet

long. Tyrannosaurus stood nearly 20 feet

tall and therefore would have towered

over Allosaurus. Its skull was twice the

length of Allosaurus's. Incredibly, it could

open its mouth a full 4 feet.

Like Allosaurus, the tyrant reptile was

bipedal. All the big meat eaters were. Its

front legs were even smaller and weaker

than those of Allosaurus. Instead of three

strong fngers armed with stout claws,

like those of Allosaurus, Tyrannosaurus

had only two feeble fngers, with claws

that could not have been any help in

either fghting or tearng of chunks of

meat. The short front legs weren't even

long enough to reach the dinosaur's

mouth. It is hard to see how they could

have been of any use at all. But what

diference did weak front legs make to

Tyrannosaurus, when it had powerful

hind legs and feet, with toes ending in

Tyrannosaurus

long curved claws like an eagle's, and

huge j aws bristling with daggerlike, saw

edged teeth six inches long!

Even though the skull of Tyranno

saurus was huge, you can see from its

shape and the size of the j aws that there

was not much room for a brain. The king

of the reptiles could not have been much

more intelligent than its small-brained

plant-eating relatives.

By the time Tyrannosaurus appeared,

the giant plant eaters were not as numer

ous in its part of the world as in the past.

The plant eaters that Tyrannosaurus

preyed on were mostly of other kinds.

The picture shows the big killer in pur

suit of the ostrichlike Ornithomimus, one

of the swifest of the lightweights. In

spite of the speed of Ornithomimus,

Tryrannosaurus, with its longer legs and

longer stride, couldn't have had much

trouble catching and eating it.

27

Plated Dinosaurs

With big meat eaters such as Allosau

rus and Tyrannosaurus around, it is not

surprising that some of the plant-eating

reptiles developed protective armor.

Among those that did were the plated

dinosaurs. As you know from the reptile

tree, the plated dinosaurs belong to the

bird-hip branch of dinosaurs. They were

no more closely related to the giant plant

eaters of the lizard-hip group than to the

giant meat eaters.

You have already twice met the

best-known plated dinosaur, Stegosaurus.

Stegosaurus lived in the days of Allosau

rus. Many pictures have been painted of

imaginary battles between the two.

Stegosaurus was from 18 to 25 feet

long, and it weighed 7 or 8 tons-much

more than a big elephant weighs. In con-

Stegosaurus

28

trast wth its meat-eating enemies, it

walked on all fours. Its hind legs were

much longer than its front ones. The

very short front legs held the big reptile's

head close to the ground. Its neck, more

over, was so short that it could not lif its

head high to look around as the giant

plant eaters could. With so little chance

of seeing enemies until it was face-to

face with them, it really needed armor to

protect it.

As you can see, its armor consisted

mainly of two rows of bony plates ex

tending down its back. In the middle of

the dinosaur's back, the plates were

about two feet tall. They made Stegosau

rus about twice as tall as a man. On its

tail it had four great spikes. Because of

its plates and spikes, Stegosaurus looked

Scel i dosaurus

.earsome, but its armor served only as

protection. The big dinosaur had no

weapons except its spiked tail, and that

was used for defense rather than attack.

It had teeth, but they were all in the

back of its mouth and were good only

for chewing.

The head of Stegosaurus was ridicu

lously small. It was small even for a

plant-eating dinosaur. Of course, there

was not much room in it for a brain, so

what brain it had was very tiny. In

common with many other dinosaurs, it

also had knots of nerve cells on its spinal

cord. The largest was between its hips.

This ganglion, in fact, was about twenty

times as large as the creature' s brain.

Sixty years or s9 ago, a newspaper

columnist wrote a jingle about Stegosau

rus which became very well known. In it

the writer said that the dinosaur was

very fortunate in having two brains. He

goes on to say:

As he thought twice before he spoke,

He had no judgments to revoke,

For he could think without congestion

Upon both sides of every question.

Clever as the jingle is, it isn't at all true.

Stegosaurus was not an intelligent ani

mal. It didn't do any real thinking with

its brain, let alone with the big ganglion

near its hips, the chief purpose of which

was to control the back legs and tail.

No other plated dinosaurs have been

found that had as well-developed plates

as those of Stegosaurus. Those of 13-foot

Scelidosaurus, one of the earliest known

of all the bird-hip dinosaurs, for in

stance, were far less spectacular.

In their time, the plated dinosaurs

i . were common around the world. Howev

er, they were the frst big group of dino

saurs to disappear.

29

Ankylosaurus

Aoky| osooros

G|oot Torto|se

Armored Di nosaurs

The armored dinosaurs flled the same

niche in the days of Tyrannosaurus that

the plated dinosaurs flled when Allosau

rus was a top carivore. Ankylosaurus is

typical of the group.

In its picture, Ankylosaurus, because

of its fatness and its spines and spikes,

may remind you of a homed toad. A

homed toad is really a lizard and is,

therefore, a very distant relative of An

kylosaurus. If you could see both ani

mals alive, however, you certainly would

not confuse them. A homed toad is only

about 6 inches long and 2 inches high.

Ankylosaurus measured some 17 feet in

length and 4 feet in height. A homed

toad, moreover, is not a plant eater, as

Ankylosaurus was, but a meat eater. Be

sides, in spite of its small horns and

30

spines, a horned toad's armor cannot

compare with an armored dinosaur's.

The armor of Ankylosaurus was much

more like that of Boreostracon, an ex

tinct mammal that lived in North and

South America in the Ice Age. They

both had shields of bony plates that cov

ered their backs, and smaller shields that

almost covered their faces, and both had

tails like war clubs. Except for some of

the turtles, Ankylosaurus was the most

fully armored reptile of all time. It could

not pull in its head and legs to get them

undercover the way a giant tortoise can,

and its sides were not as well protected,

but it still deserved to be called, as it of

ten has been, an armored tank.

The plates of bone that formed the

shield on the back of Ankylosaurus had

.

bony bumps that made for better protec

tion. Along its edges, the shield had

bony spikes extending outward. The tail,

which was protected by rings of bone,

ended in a ball of solid bone.

Ankylosaurus needed its coat of mail,

for it was a slow-moving creature, with

legs so short and a head so close to the

ground that it had an even poorer

chance of seeing approaching enemies

than Stegosaurus had. It had no combat

weapons except its tail. Its teeth were

weak and good only for eating plants.

The teeth, moreover, like those of Stego

saurus, were all in the back of its jaws,

not in front, where teeth good for biting

need to be. Its tail, however, must ofen

have helped Ankylosaurus fght of ene

mies. One swing of it might well have

persuaded a meat eater to hunt for its

dinner somewhere else. If you have ever

seen a big lizard, such as an iguana,

fghting of an enemy with its tail, you

know what a powerful weapon a lashing

Pol acanthus

tail can be. The tail club of Ankylosau

rus must have made its tail truly lethal.

The way the bony plates in the armor

of Ankylosaurus were fused with bones

in its skeleton gave the dinosaur its

name. Ankylosaurus means "fused liz

ard, " or "stif lizard. "

Fossils of Ankylosaurus have been

found only in North America. Other

armored dinosaurs, however, were scat

tered far and wide over the earth. Fossils

of several diferent kinds, much like

Ankylosaurus, have been found in Afri

ca, Asia, Europe, and South America.

Polacanthus, the early armored dino

saur pictured below, is known from fos

sils found in England. This dinosaur,

only 14 or 15 feet in length, was not

quite as large as Ankylosaurus. It was

not as well armored as Ankylosaurus,

either. But with all those spines down

the sides of its back, it could not have

been easy prey for even the hungriest

giant meat eaters that came its way.

3 1

Parasaurol ophus

Duckbi l l s, Boneheads, and Parrot Beaks

Fortunately for Tyrannosaurus and the

other big meat-eating dinosaurs of its

time, there were plenty of plant-eating

dinosaurs that made far easier prey than

the plated and armored ones. Among

them were the duckbills, big dinosaurs of

the bird-hip group. The duckbills were

common in the days of Tyrannosaurus

as common as deer are in ours.

The duckbills were descendants of

Camptosaurus, a 7-foot bipedal dinosaur

that, in ah earlier period, had browsed

the forests alongside Stegosaurus. Except

in size, they were still very much like

their small ancestor. One picture on page

15 shows Camptosaurus.

32

All three dinosaurs pictured here are

duckbills. One of them, Trachodon, is so

famous that many people think of it as

the only duck-billed dinosaur.

Trachodon was about 30 feet long. It

could walk on all fours, but it ofen

walked on just its heavy hind legs. It

stood about 1 8 feet tall, almost tall

enough to look Tyrannosaurus straight in

the eye-if, that is, it would ever have got

that close to the king of the dinosaurs.

Trachodon spent most of its time in

marshes and sluggish streams. It ate

plants growing in the water and along its

edges. Like all the duckbills, it had a

broad, fattened bill much like a duck' s.

lambeosaurus

In the front of its jaws, it had no teeth.

However, in the back, it had rows and

rows of peglike teeth good only for

grinding up its food. Its teeth were

crowded together, like the stones in an

old-fashioned cobblestone pavement.

The dinosaur's name of Trachodon

means "rough tooth. " When we lose one

of our baby teeth, a tooth that has been

hidden in the jaw takes its place. Each of

Trachodon's teeth could be replaced sev

eral times. Altogether, Trachodon had

many hundreds of teeth.

To go with its ducklike bill, Trachodon

had webbed feet. There were three toes

on each hind foot. Strangely enough for

Trachodon

a reptile, each toe ended in a small hoof.

On each front foot, or hand, Trachodon

had three fngers with hooves and one

very small fnger without either a hoof or

a claw.

Although Trachodon must have walked

about on shore part of the time, either

on two feet or on four, its powerful hind

legs, with their webbed feet, doubtless

made for greater speed in water than on

land. Its big crocodilelike tail must have

helped, too, in pushing it through the

water faster.

Scientists have found in rocks casts of

Trachodon's skin-casts made from the

imprint of the skin in the wet mud. They

33

show that it was covered with small

scales. They indicate also that the skin

had diferent color patterns but, of

course, give no hint of what the diferent

colors were.

Except for their strange-looking skulls,

Lambeosaurus and Parasaurolophus

were very much like Trachodon. Para

saurolophus had a long horlike proj ec

tion growing from the back of its head.

Lambeosaurus had a crest on the top of

its head, with a long prong going back

from the crest. Lambeosaurus was named

afer a famous Canadian geologist, L. M.

Lambe. Parasaurolophus means "like a

crested lizard. "

Shown along with Trachodon in the

picture on this page is Corythosaurus,

Corythosaurus

another duckbill with a big crest on its

head. The name Corythosaurus means

"helmeted lizard. " The crest looks a little

like a rooster's comb, but, unlike a comb, it

was made of bone.

No one is certain about how these

crests of various shapes were helpful.

Inside them there were air tubes. Per

haps they stored air which the dinosaur

could somehow use when its head was

underwater. Perhaps they were simply

traps to keep water from getting into the

dinosaur's lungs. They may even have

had something to do with smell. No one

really knows.

There were duckbills of many other

kinds. The four you have just read about

lived in North America, but there were

Trachon

duckbills in other parts of the world as

well. Many fossils of them have been

found in Europe and Asia.

None of the duckbills had any kind of

protective armor. Since all of them were

at home either in ponds and swamps or

on land, their chief way of saving them

selves from the . truly terrible dinosaurs of

the time may well have been, as with the

giant plant eaters, to retreat into the

safety of the water.

Pachycephalosaurus was not a duck

bill. Rather, it belonged to a closely related

family of dinosaurs known as boneheads.

The name Pachycephalosaurus means

"thick-headed lizard. " It is certainly

suitable, for over the creature's tiny

brain there was a several-inches-thick

dome of solid bone. Pachycephalosaurus

had not only a great dome of bone over

its brain but also strange bumps and

spikes of bone decorating its head and

face. Certainly it would never have taken

a prize in a beauty contest.

Pachycephalosaurus spent much of its

time in the water and ate water plants,

just as the duckbills did. It was not as

large as most of the duckbills, being only

20 feet or so long. Like many of the

Pachycephal osaurus

duckbills, Pachycephalosaurus lived in

North America.

Psitticosaurus, another duckbill rela

tive, lived in e

a

stern Asia. Its beak was

much more like a parrot's than like a

duck's. The name Psitticosaurus means

"parrot lizard. "

Psitticosaurus was not very big. It

measured only 4 feet in length. Although

it was so small,

-

scientists consider it

important, for, they believe, the parrot

beaks were ancestral to - the great homed

dinosaurs.

Psitticosaurus

35

Protoceratops

Horned Dinosaurs

Protoceratops was, in a way, the be

ginning of the end for the dinosaurs. It

was one of the frst of the horned dino

saurs, the last dinosaur group to appear.

Protoceratops means "before-horn face. "

Though it was a horned dinosaur, Proto

ceratops had no hor. But it did have a

big bony frill that protected its neck, just

as other hored dinosaurs had. It had

also the stout parrotlike beak that the

horned dinosaurs inherited from their

parrot-beak ancestors.

Protoceratops was only about 6 feet

long-small for a horned dinosaur. Like

all bird-hip dinosaurs, it ate plants. In

addition to teeth in the back of its jaws,

it had four tiny ones in the front. Later

horned dinosaurs had no front teeth and

were much larger.

Protoceratops lived in eastern Asia. It

has won fame chiefy because of its eggs.

The frst dinosaur eggs ever discovered

along with the fossil bones of the dino

saur thought to have laid them were Pro

toceratops eggs. They were found in a

desert region of Mongolia. The eggs,

now petrifed and brown, had been laid

36

in a hollow in the sand, just as the eggs

of sea turtles are laid today. The mother

dinosaur had then covered them with

sand, but instead of going away and

leaving her eggs, as turtles do, she had

.

Styracosaurus

apparently stayed nearby to guard them.

Crocodiles of today are known to stay

near their nests. In one Protoceratops egg

that had in some way been broken open

sometime before it was ready to hatch,

the bones of the baby dinosaur can be

seen quite clearly.

Styracosaurus and Monoclonius were

two of the later horned dinosaurs. Styra

cosaurus means "spike lizard, " and

Monoclonius "one conqueror. " The frst

of these names comes from the spikes on

this dinosaur's big collar, the other from

the single weapon, the horn on its nose,

of Monoclonius. Both of these dinosaurs

fourished in North America.

Styracosaurus was some 15 feet long.

Its weight was about 4 tons. Its head

and collar together measured about 6

feet-over one-third the animal's length.

The horn in the middle of its nose was

Monocl oni us

nearly 2 feet long and 6 inches thick, and

some of the spines on its collar were a

yard long. The creature was clumsy,

slow-moving, and dim-witted. Except for

its horn and its fence of spikes, it would

have been easy prey for a big meat eater.

Its enormous beak, though a powerful

cutting tool, was used chiefy for nipping

of parts of plants to eat.

Monoclonius measured about 18 feet.

Its fortunes in battle hinged largely on its

single weapon, the long, sharp horn on

its nose. If the horn failed to be efective,

Monoclonius lost the battle.

The huge lizard-hip plant eaters like

Brontosaurus and Diplodocus, as you

know, are thought to have spent much of

their time in the water. So did the duck

bills, say the scientists. The horned dino

saurs, in contrast, were strictly land ani

mals, thus needing their weapons.

Easily the best known of the horned

dinosaurs is Triceratops. The name

means "three-homed face. " Where it

came from is clear: Triceratops had a

hom over each eye and one on its nose.

Like Styracosaurus and Monoclonius,

Triceratops was a North American dino

saur. Many, many fossils of it have been

found in Wyoming, Montana, and Col

orado. Scientists believe that great herds

of Triceratops roamed the western

plains, just as herds of bison did millions

of years later. In fact, the horns of Tri

ceratops were so much like those of a

bison that the frst ones discovered were

mistaken for bison horns.

Triceratops was, of course, far bigger

than a bison. A full-grown bison is about

1 1 feet long and weighs only about l 1h

Tyrannosaurus

38

tons. Triceratops was some 25 feet long

and weighed about 12 tons, nearly twice

as much as an African elephant, the larg

est land animal of today.

This big homed dinosaur looked more

like a rhinoceros than like any other

modem animal. But it was about twice

as long and weighed several times s

much as any rhinoceros. The hom on its

nose was about 3 feet long, roughly the

length of the big front hom of a white

' rhinoceros. The two horns over its eyes,

however, were much longer. They mea

sured 6 feet or more. Of course, no rhi

noceros has a faring ruf of bone like that

o

f Triceratops.

As in all the bird-hip dinosaurs, the

hind legs of Triceratops were much long

er than its front legs. The legs were all

sturdy. On its hind feet it had four

stubby toes, on which there were hooves.

The front feet had fve toes each, two of

which, the two on the outside, were

rather small. The three larger toes had

little hooves.

Triceratops and its close relatives, al

though they were plant eaters, did not

have the huge number of teeth the duck

bills had. In the back of both its jaws,

Triceratops had only a single row of

teeth at each side.

Tyrannosaurus was the great enemy of

Triceratops. But Triceratops certainly

was no easy mark for the giant meat eat

er. The big hored dinosaur was very

much a battler. Apparently secure in its

defenses, instead of retreating from the

enemy, it stood ground and fought

fercely. Its big bony collar gave Tricera

tops good protection for its neck, the

area where meat eaters often attack their

Triceratops

prey. Its sharp horns could easily rip

open the sides or belly of a big, charging

meat eater.

The weapons and protective armor of

Triceratops, however, were all in front.

So long as Triceratops could face the

tyrant meat eater, it had a good chance

of winning a battle. Even if Tyrannosau

rus started to move around Triceratops

to attack its side or rear, Triceratops

might well be able to slash with a side

wise movement of its head. If Triceratops

was alone and separated from all other

members of its herd, and if a second or

third Tyrannosaurus came to join in the

battle, the scrappy dinosaur probably

had no chance to escape being a meal.

Triceratops appeared near the end of

the Cretaceous, the third and the last act

of the great reptile show of the Mesozoic.

When it disappeared, the days of the

dinosaurs were over.

Fl yi ng Repti l es

The fying dragon of today is a lizard.

In spite of its name, this small lizard

does not really fy. Its "wings" are simply

faps of skin that act rather like the

wings of a glider. The fying reptiles, or

pterosaurs, of dinosaur days really did

fy. Pterosaur means "winged lizard. "

Although their wings were true wings,

the fying reptiles did not look much like

They had no feathers but instead

were covered with hair fbers. Their

wings were not nearly such good fying

devices as a bird's wings are. A pterosaur

could not make the many diferent

movements with its wings that most birds

can. It could not make any of the smaller

movements a bird can make just by

moving its wing feathers. A pterosaur's

wings were sheets of skin stretched from

the ver long fourth fngers of its "hands"

to its hind legs. The whole wing had to

be moved, or fapped, as one piece.

Rhamphorhynchus

But in some ways, the pterosaurs were

like their warm-blooded cousins. Scien

tists think that they, too, were probably

at least somewhat warm-blooded. Many

of their bones, as with birds, were hol

low. Also, like birds, they had good

vision and a poor sense of smell.

Rhamphorhynchus was one of the

early pterosaurs. It lived during the Ju

rassic, the time of Brontosaurus and Di

plodocus. Its name, which sounds like

something out of a fairy tale, means

"crooked beak. " From the tip of that

beak to the end of its long reptilian tail,

Rhamphorhynchus was only about IS

inches long. At the end of the tail, there

was a rudder that served much the same

purpose as the tail of a kite.

In its jaws, Rhamphorhynchus had

many sharp teeth, all pointing forward.

Their chief use, apparently, was for

spearing fsh. Probably Rhamphorhyn

chus spent most of its time gliding low

over the water, looking for fsh. Hollow

bones made it light enough for gliding.

Ordinary walking, either on two legs

or four, may have been impossible for

Rhamphorhynchus. When it was not

fying, perhaps it rested by hanging itself

up by its claws, much as bats do.

Pterodactylus was a somewhat later

pterosaur, though it, too, appeared in the

Jurassic. It was the most common fying

reptile of the period. The creature

ranged from the size of a sparrow to that

of a goose. It had only a ver short tail,

but in other ways it looked much like

Rhamphorhynchus. The fying reptile

pictured on page 15 is Pterodactylus.

/

The name Pterodactyl us means , "wing

fnger. " It is a good name for any ptero

saur. In fact, pterodactyl is ofen used

interchangeably with pterosaur.

The giant of the pterosaurs was Pter

anodon. Like Pterodactylus, it had a very

short tail, but it had an enormous an

vil-shaped head and very large wings.

The outspread wings measured about 27

feet from tip to tip. On the basis of wing

spread, it was the largest fying creature

of all time.

Pteranodon had no teeth in its long

beak. Its name means "toothless wing. "

A crest went as far backward from the

top of Pteranodon's head as its beak

went forward. Perhaps the crest balanced

the big jaws and made it easier for the

creature to hold its head up. Perhaps it

acted as a rudder.

Pteranodon

Like toothy Rhamphorhynchus, tooth

less Pteranodon, too, probably spent

most of its time soaring out over the sea,

looking for fsh. It may even have slept

in the air. Probably its eggs were laid

high up on clifs, where there were likely

to be upward-moving drafs of air.

Pteranodon fourished in the Creta

ceous, in the days of Triceratops and

Tyrannosaurus, but this big pterosaur

disappeared before Tyrannosaurus and

Triceratops did. The heyday of the fying

reptiles was in the late Jurassic and early

Cretaceous. There were birds then, but

they were not well enough developed to

rival the fying reptiles. By the time Pter

anodon appeared, the birds were real

rivals, and the fying reptiles fnally lost

out. The disappearance of Pteranodon was

the end of the pterosaurs.

41

Ichthyosaur

Mari ne Repti l es

As you know, the dinosaurs were land

animals. Not one of them lived in the

sea. In their time, though, there were

many marine reptiles, among them

ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, sea turtles, sea

crocodiles, and mosasaurs, or sea lizards.

Only the sea crocodiles were close rela

tives of the dinosaurs.

The marine reptiles of the Mesozoic

did not drive the fshes out of the seas.

Fishes still abounded, as they had for

many millions of years, and some were

very large. One measured over 30 feet.

Sharks were common. Many of the fshes

made good prey for the sea reptiles.

The name ichthyosaur means "fsh liz

ard. " The frst ichthyosaur bones that

were found were thought to be fsh

bones. In shape, the ichthyosaurs were

much more like fshes than any of the

other marine reptiles. Their bodies were

streamlined. They had fippers much the

shape of fshes' fns. Their tail was very

42

diferent from the tail of any land rep

tile. Like a fsh's tail fn, it was an excel

lent propeller. The ichthyosaurs were fast

swimmers.

An ichthyosaur's mouth was full of

sharp, strong teeth. A fsh once caught

had little chance to get away. The eyes

of ichthyosaurs were enormous. Perhaps,

some scientists think, these fshli

k

e rep

tiles did most of their hunting at night,

when the light was dim.

There were great ichthyosaurs over 35

feet long. The average length, however,

was only 10 feet or so. Fossils of ichthyo

saurs have been found in many diferent

places. They were successful inhabitants

of seas all over the world. These reptiles

were probably better ftted for living in

the sea than any others in earth history.

They were bound strictly to the water,

for their fippers could not possibly have

served as legs. The ichthyosaurs could

not even crawl up onto land to lay their

eggs, as sea turtles do today. Their young

were born alive, in the sea.

Probably these fsh-lizards swam in

schools, as dolphins do now. Since they

could not breathe underwater, they had

to come to the surface ofen for air, just

as dolphins have to.

It is easy to recognize Archelon as a

turtle. So far as anyone knows, it was the

largest one that ever lived. It grew to a

length of 12 feet. The skull alone was a

yard long. Archelon had enormous pad

dles that pushed it rapidly through the

water. The big sea turtle was well ar

mored, as it needed to be, as protection

against sharks and some of the ferce

meat-eating reptiles that shared the seas

with it.

Today's crocodiles are found in

swamps, in streams that empty into the

sea, or in shallow waters along seashores.

Ofen they climb out of the water to lie

on the banks or shores. The crocodiles of

the Age of Reptiles, too, were mostly

Archei on

shallow-water prowlers, but some took to

living in the ocean. These were the sea

crocodiles. The legs of these crocodiles

had become paddles and their crocodile

tail a fshlike one, much like the tail of

an ichthyosaur. The sea crocodiles were

abundant for a while, then disappeared.

Trinacromerum, the 10-foot-long sea

reptile pictured with Archelon, was a

plesiosaur. The name plesiosaur means

"neighbor of lizards. " A German name

for plesiosaur means "swan-necked

dragon. " Swan-necked dragon hardly

seems a good name for Trinacromerum,

with its long crocodilelike snout and

rather short, thick neck. But the name is

a good one for the kind of plesiosaur it

was meant for. This plesiosaur had a

long, slender neck which, when held up

out of the water as the plesiosaur swam

near the surface, would have looked

swanlike.

The body of even a long-necked ple

siosaur was not slender. It was much the

Trinacromerum

El asmosaurus

44

shape of a turtle's. In fact, it has been

said of the long-necked plesiosaurs that

they looked as if they had started out to

be turtles and then changed their minds

and decided to be snakes.

Elasmosaurus was the long-necked

plesiosaur giant. Here are the measure

ments of one 42-foot fossil specimen:

head, 2 feet; neck, 23 feet; body, 9 feet ;

tail, 8 feet. Like other plesiosaurs, Elas

mosaurus ofen fopped up onto land. It

had to lay its eggs on land.

Portheus-a l arge fsh

There were plesiosaurs in the seas all

during the days of the dinosaurs. Fossils

of them have been found in many

diferent places, but they are not as

numerous as fossils of ichthyosaurs.

Tylosaurus was a mosasaur. The mosa

saurs lived in the days of Tyrannosaurus.

Many fossils of them have been found

with fossils of that "neighbor of lizards,"

Elasmosaurus.

The mosasaurs swam by wriggling

from side to side, much as snakes do.

They had paddles, but these served

chiefy as rudders. The sea lizards were

fast swimmers. They and the sharks were

the chief enemies of the ichthyosaurs.

Of all the reptiles of the Mesozoic that

went to sea, the only ones with close rei- .

atives among living reptiles are the sea

turtles, the sea lizards, and the sea croco

diles. Even though they dominated the

sea for many millions of years, the ich

thyosaurs and the plesiosaurs went the