Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Cortese Et Al 2008-Critical Reviews in Food Science

Încărcat de

eduardobar2000Descriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cortese Et Al 2008-Critical Reviews in Food Science

Încărcat de

eduardobar2000Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

This article was downloaded by: [Columbia University] On: 18 May 2012, At: 14:43 Publisher: Taylor &

Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/bfsn20

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Obesity: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Samuele Cortese M.D.

a a b

, Marco Angriman M.D. , Claudio Maffeis M.D. , Pascale Isnard

a a b b

M.D. , Eric Konofal M.D., Ph.D. , Michel Lecendreux M.D. , Diane Purper-Ouakil M.D., Ph.D.

a a d

, Brenda Vincenzi M.D. , Bernardo Dalla Bernardina M.D. & Marie-Christine

a

Mouren M.D.

AP-HP, Child and Adolescent Psychopathology Unit, Robert Debr Hospital, Paris VII University, Paris, France

b

Child Neuropsychiatry Unit, G.B. Rossi Hospital, Department of Mother-Child and BiologyGenetics, Verona University, Verona, Italy

c

Pediatric Unit, G.B. Rossi Hospital, Department of Mother-Child and Biology-Genetics, Verona University, Verona, Italy

d

INSERM U 675 Analyse Phnotypique, Dveloppementale et Gntique des Comportements Addictifs, Facult Xavier Bichat, 75018, Paris, France Available online: 05 Jun 2008

To cite this article: Samuele Cortese M.D., Marco Angriman M.D., Claudio Maffeis M.D., Pascale Isnard M.D., Eric Konofal M.D., Ph.D., Michel Lecendreux M.D., Diane Purper-Ouakil M.D., Ph.D., Brenda Vincenzi M.D., Bernardo Dalla Bernardina M.D. & Marie-Christine Mouren M.D. (2008): Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Obesity: A Systematic Review of the Literature, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 48:6, 524-537 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10408390701540124

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 48:524537 (2008) Copyright C Taylor and Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1040-8398 DOI: 10.1080/10408390701540124

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Obesity: A Systematic Review of the Literature

SAMUELE CORTESE, M.D.,1,2 MARCO ANGRIMAN, M.D.,2 CLAUDIO MAFFEIS, M.D.,3 PASCALE ISNARD, M.D.,1 ERIC KONOFAL, M.D., PH.D.,1 MICHEL LECENDREUX, M.D.,1 DIANE PURPER-OUAKIL, M.D., PH.D.,1,4 BRENDA VINCENZI, M.D.,2 BERNARDO DALLA BERNARDINA, M.D.,2 and MARIE-CHRISTINE MOUREN, M.D.1

AP-HP, Child and Adolescent Psychopathology Unit, Robert Debr Hospital, Paris VII University, Paris, France e Child Neuropsychiatry Unit, G.B. Rossi Hospital, Department of Mother-Child and Biology-Genetics, Verona University, Verona, Italy 3 Pediatric Unit, G.B. Rossi Hospital, Department of Mother-Child and Biology-Genetics, Verona University, Verona, Italy 4 INSERM U 675 Analyse Ph notypique, D veloppementale et G n tique des Comportements Addictifs, e e e e Facult Xavier Bichat, 75018 Paris, France e

2 1

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

Recent studies suggest a possible comorbidity between Attention-Decit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and obesity. To gain insight into this potential association, we performed a systematic review of the literature excluding case reports, nonempirical studies, and studies not using ADHD diagnostic criteria. Empirically based evidence suggests that obese patients referred to obesity clinics may present with higher than expected prevalence of ADHD. Moreover, all reviewed studies indicate that subjects with ADHD are heavier than expected. However, data on the prevalence of obesity in subjects with ADHD are still limited. As for the mechanisms underlying the potential association between ADHD and obesity, ADHD might lead to obesity via abnormal eating behaviors, impulsivity associated with binge eating might contribute to ADHD in obese patients, or, alternatively, both obesity and ADHD might be the expression of common underlying neurobiological dysfunctions, at least in a subset of subjects. In patients with obesity and ADHD, both conditions might benet from common therapeutic strategies. Further empirically based studies are needed to understand the potential comorbidity between obesity and ADHD, as well as the possible mechanisms underlying this association. This might allow a more appropriate clinical management and, ultimately, a better quality of life for patients with both obesity and ADHD. Keywords obesity, overweight, ADHD, inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, pharmacological treatment

INTRODUCTION Attention-Decit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common childhood psychiatric disorders, estimated to affect 510% of school-aged children worldwide (Biederman, 2005). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th edition (DSM-IV) (APA, 1994) and its updated version (Text Revision, TR) (APA, 2000), ADHD is dened by a persistent and age-inappropriate pattern of inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity, or both. Onset before the age of seven and impaired functioning in two or more settings are reAddress correspondence to: Samuele Cortese, M.D., Service de Psychopathologie, de lEnfant et de lAdolescent, H pital Robert Debr , 48 Bouleo e vard S rurier, 75019 Paris, France. Tel : +33140032263, Fax: +33140032297. e E-mail: samuele.cortese@gmail.com

quired for the diagnosis. The DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and IV-TR (APA, 2000) dene four types of ADHD: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, combined, and not otherwise specied. Decits in executive functions, including inhibition, working memory, planning, and sustained attention, are common, although far from universal, in ADHD (Biederman and Faraone, 2005). Impairing symptoms of ADHD may persist into adulthood in up to 60% of cases (Kessler et al., 2005). Stimulants (methylphenidate and amphetamines) are the rst-line FDA-approved pharmacological treatment, followed by the non-stimulant atomoxetine (Pliszka et al., 2006). It is well known that ADHD is frequently associated with psychiatric and developmental disorders such as Oppositional Deant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, Anxiety Disorders, Depressive Disorders, Speech and Learning Disorders (Dulcan,

524

ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD) AND OBESITY

525

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

1997).7 Although overlooked in the past, a possible new comorbidity between ADHD and obesity has been suggested by recent studies (Agranat-Meged et al., 2005; Altfas, 2002; Curtin et al., 2005; Fleming et al., 2005; Holtkamp et al., 2004; Lam and Yang, 2007). A better insight into this potential comorbidity is of relevance for two reasons. First, it may contribute to the understanding of possible pathological mechanisms underlying both ADHD and obesity, at least in a subset of patients. Second, from a clinical standpoint, it might have important implications for the management of patients with both obesity and ADHD, suggesting common and potentially effective therapeutic strategies for these two conditions when they coexist. This seems particularly noteworthy because of the high prevalence and the enormous personal, familiar, and social burden associated with both obesity (Dietz and Robinson, 2005; Malecka-Tendera and Mazur, 2006; Speiser et al., 2005) and ADHD (Biederman, 2005). In light of these considerations, the aims of this paper were: 1) to systematically review empirically based evidence on the relationship between ADHD and obesity; 2) to examine the mechanisms which have been proposed to underlie the potential comorbidity between obesity and ADHD; 3) to discuss the implications of this possible comorbidity on the clinical management of patients who present with both ADHD and obesity.

cluded any papers published before 1980 (when the American Psychiatric Association rst published the DSM-III). Reference lists from each relevant paper were examined to determine if any relevant studies had been missed during the database searches. Studies of both children and adults were considered. Case reports and descriptive studies with no statistical analyses of data were excluded, as well as unpublished data (e.g., unpublished doctoral dissertations). Finally, since drugs used for the treatment of ADHD may have anorexigenic effects, studies examining weight status in treated subjects with ADHD or studies which did not control for the effect of treatment were not considered.

Results The database searches (1980-January 2007) yielded the following results: ADHD and obes*: 40 references; attentiondecit/hyperactivity disorder and obes*: 40 references; inattenti* and obes*: 4 references; hyperactiv* and obes*: 217 references; impulsiv* and obes*: 49 references; ADHD and overweight: 24 references; attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder and overweight: 21 references; inattenti* and overweight: 4 references; hyperactiv* and overweight: 125 references; impulsiv* and overweight: 38 references; ADHD and weight: 505 references; attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder and weight: 326 references; inattenti* and weight: 90 references; hyperactiv* and weight: 1554 references; impulsiv* and weight: 291 references; obes* and psychiatr*: 1810 references; obes* and psycholog*: 6497 references; obes* and psychopatholog*: 249 references; overweight and psychiatr*: 6 references; overweight and psycholog*: 5746 references; overweight and psychopatholog*: 221 references. Eight studies (Carey et al., 1988; Hellgren et al., 1993; Hwang et al., 2006; Lumeng et al., 2003; Rojo et al., 2006; Strauss et al., 1985; Tersha Kovec et al., 1994; Zeller et al., 2004; McGee et al., 1985) examining symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivityimpulsivity in obese subjects were not included in our review since they did not use formal diagnostic criteria for ADHD. Results of the study by Vila et al. (2004) were not considered because the authors did not perform statistical analyses on the prevalence of ADHD in their sample. The study by Sarwer et al. (2006) was also excluded given the lack of a control group. After excluding any other non-pertinent studies, we retained ten studies (Curtin et al., 2005; Holtkamp et al., 2004; Lam and Yang, 2007; Anderson et al., 2006; Biederman et al., 2003; Faraone et al., 2005; Spencer et al., 1996, 2006; Swanson et al., 2006; Hubel et al., 2006) evaluating the weight status of subjects with ADHD and ve studies (Agranat-Meged et al., 2005; Altfas, 2002; Fleming et al., 2005; Erermis et al., 2004; Mustillo et al., 2003) assessing the prevalence of ADHD in obese vs. control subjects. Among the studies examining the prevalence of ADHD in obese subjects, we included the report by Fleming et al. (2005). Although these authors did not perform a formal

Systematic Review of the Literature In order to gain insight into the relationship between ADHD and obesity, we searched for studies: 1) assessing the prevalence of ADHD in obese subjects; 2) evaluating the weight status of subjects with ADHD. To this purpose, a PubMed search was performed using the following keywords in various combinations: ADHD, attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder, inattenti,* hyperactiv,* impulsiv,* obes,* overweight, weight. Moreover, the terms obes* and overweight were cross-referenced separately with psychiatr,* psychopatholog,* and psycholog* to look for any additional studies on the relationship between obesity and psychopathology, including ADHD. Since the diagnosis of ADHD is based on standardized criteria, studies that analyzed the relationship between obesity and ADHD traits (i.e. symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity or impulsivity), without using formal diagnostic criteria, were not considered. ADHD was differently dened in the previous editions of the DSM. The DSM-III (APA, 1980) included the denition of Attention Decit Hyperactivity Disorder, similar to the combined type of the DSM-IV (APA, 1994). The DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) included Attention Decit either With or Without Hyperactivity, similar, respectively, to the combined and inattentive type of the DSM-IV (APA, 1994). Given these similarities, studies based on DSM-III (APA, 1980) or III-R (APA, 1987) criteria were retained in our systematic review. On the other hand, the DSM-I (APA, 1952) and II (APA, 1968) were not based on empirical data and explicit diagnostic criteria. Therefore, we ex-

526

S. CORTESE ET AL.

diagnosis of ADHD, they used a questionnaire with high sensitivity to detect ADHD. Moreover, they combined data from different questionnaires to classify the subjects as likely cases of ADHD. Therefore, although recognizing that this is not the standardized procedure to diagnose ADHD, the methodology used by Fleming et al. (2005) allowed a valid approximation of ADHD formal diagnosis. The studies retained in our systematic review will be discussed in the following sections.

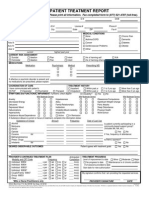

Studies Examining the Prevalence of ADHD in Obese Subjects (Table 1) The rst report on the prevalence of ADHD in obese subjects was provided by Altfas (Altfas, 2002). In a retrospective review of a clinical sample of 215 obese adults receiving obesity treatment in a bariatric clinic, the author found that 27.4% of all patients presented with ADHD according to DSM-IV criteria (AD), well above the prevalence of ADHD in the general adult population (about 4%) (Biederman and Faraone, 2005). Moreover, 33.5% had ADHD symptoms not meeting full DSM-IV criteria (ADSx), while 39.1% did not report ADHD symptoms (NAD). After dividing the patients into four obesity classes according to the NIH classication (NIH, 1998) (class III: extreme obesity, BMI 40; class I and II: obesity, BMI: 30 to 39.9; and overweight, BMI: 25 to 29.9), the proportion of patients having ADHD in obesity class III (42.6%) was signicantly higher than those in obesity class I-II and overweight class (22.8% and 18.9 %, respectively) (p = 0.002). Moreover, analysis of variance of patients BMI at the start of treatment showed a signicant difference among the group means (p = 0.003), with AD having a higher BMI (39.2) than ADSx (35.5) and NAD (34.6). Fisher multiple comparison test found AD differed from ADSx and NAD (AD-ADSx: p = 0.001, AD-NAD: p = 0.01). In another study, Erermis et al. (2004) assessed the frequency of mental disorders in a sample of 30 obese adolescents (aged 1216 years) seeking treatment from a pediatric endocrinology outpatient clinic, in a non-clinical obese group of 30 obese adolescents matched for age and sex, and in an age and sex-matched control group of 30 normal weight adolescents. Subjects with mental retardation, chronic physical illness and bipolar disorder, or other psychotic disorders were excluded. The authors used a non-structured psychiatric interview based on DSMIV criteria to diagnose several psychiatric disorders, including ADHD. They found that the prevalence of ADHD was signicantly higher in the clinical obese group (13.3%) in comparison to the non-clinical obese group (3.3%) and the control group (3.3%). One major limitation of the study is the relatively small sample size. Moreover, the mean BMI was signicantly lower in non-clinical obese subjects vs. clinical obese adolescents, limiting the validity of the comparison of psychopathology rates between clinical and non-clinical obese subjects. The potential comorbidity between ADHD and obesity was conrmed by Agranat-Meged et al. (2005) in a sample of

26 children (13 male, age range: 817 years) hospitalized in an eating disorder unit for the treatment of their refractory morbid obesity (BMI > 95th percentile). A very high portion of the participants (57.7%) presented with ADHD according to DSMIV criteria (conrmed by the semi-structured interview Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version, K-SADS-PL (Kaufman et al., 1997)). This proportion was signicantly higher than that (10%) found in the general population in the same age group (p < 0.0001). The prevalence of ADHD was particularly elevated in boys (76.9%) but was also signicant in girls (38.5%). Interestingly, 60% of the participants had the combined type of ADHD, while 40% were diagnosed with the predominantly inattentive type. The exclusion criteria (IQ < 80, developmental or neurological disorders, obesity related to known medical causes) were intended to reduce the sample bias that might have interfered with the assessment of ADHD. However, the results of this study should be considered with caution given that they refer to a small clinical sample of hospitalized morbidly obese children. The authors pointed out that the selection bias may not have been relevant, since the prevalence ratio of the subtypes of ADHD and the sex ratio of ADHD participants resembled more that of community than clinical populations. Although the lack of a clinical control group is the major limitation of the study, Agranat-Meged et al. (2005) reported that a retrospective chart review of their patients with anorexia nervosa revealed a prevalence of ADHD similar to the rate prevalence in the general population (4.8%), and, therefore, lower than that found in their obese patients. As previously stated, although the study by Fleming et al. (2005) did not use a formal diagnosis of ADHD, it was included in our review since the authors used a highly sensitive instrument to detect ADHD and combined data from different questionnaires to obtain a likely diagnosis of ADHD. In a sample of 75 obese women (mean age: 40.4 years; BMI 35) consecutively referred to a medical obesity clinic, these authors evaluated ADHD symptoms using the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) (Ward et al., 1993). This is a 61-item retrospective survey of behaviors characteristic of childhood ADHD. It has been found that a cut-off score of 36 on a subset of 25 core items from the WURS (WURS-25) could correctly classify 96% of individuals identied as meeting adult criteria for ADHD (Wender, 1995). Moreover, Fleming et al. (2005) used the Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) (Conners et al., 1999) (a measure of current symptoms of ADHD made up of 7 subscales), and the Brown ADD Scale for Adults (Brown, 1996), that measures ve functions, including attention, but not hyperactivity or impulsivity. It was found that 38.6% of the participants scored at or above the cut-off of 36 on the WURS, signicantly higher than the 4% prevalence previously reported in a normal sample ( p < 0.001) (Ward et al., 1993). The inattention-memory, the impulsivity-emotionality, the DSM-IV-inattentive, and the ADHD-index subscales scores of the CAARS were signicantly higher than the expected frequency (p < 0.001). On the contrary, the hyperactive-restless and the DSM-IV-hyper-impulse

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD) AND OBESITY

527

Table 1 Studies examining the prevalence of ADHD in obese subjects. Case reports, non empirical studies and studies not using standardized ADHD diagnostic criteria were excluded First author (year) Altfas (2002) Subjects 215 obese adults treated in a bariatric clinic Mean age (SD)/age range (years) 43.4 (10.9) Key results 27.4% of all patients presented with ADHD. The proportion of patients having ADHD in obesity class III (42.6%) was signicantly higher than those in obesity class I-II and overweight class (22.8% and 18.9 %, respectively) (p = 0.002). Patients with ADHD had a signicantly higher BMI (39.2) than patients without ADHD (34.6) (p = 0.01) The prevalence of ADHD was signicantly higher in the clinical obese group (13.3%) in comparison to the non-clinical obese group (3.3%) and the control group (3.3%) Comments Strength: the rst report on the prevalence of ADHD in obese subjects Limitations: lack of control group (rates of ADHD in obese subjects were compared with those in the general population); comorbid conditions (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea, depression, and anxiety disorders) were not controlled for Strengths: subjects with mental retardation, any chronic physical illness or a diagnosis of bipolar disorder/ psychotic disorders were excluded Limitations: small sample size; a non structured interview was used to diagnose ADHD; BMI was signicantly lower in non-clinical obese subjects vs. clinical obese adolescents Strength: subjects with mental retardation, medical causes of obesity or developmental/neurological disorders were excluded Limitations: lack of control group; small sample size Strength: symptoms of both childhood and adult ADHD were assessed Limitations: no formal diagnosis of ADHD; psychiatric comorbid disorders were not controlled for; lack of control group

Erermis et al. (2004)

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

30 obese adolescents (clinical), 30 obese adolescents (non clinical), 30 normal weight adolescents

Clinical group: boys : 13.8 (1.2) girls : 13.8 (1.3)

Agranat-Meged et al. (2005)

26 obese children in a pediatric eating disorder unit

13.04 (2.78)

57.7% of children presented with ADHD vs. estimates of 10% in the general population in the same age group (p < 0.0001).

Fleming et al. (2005)

75 obese women consecutively referred to a medical obesity clinic

40.4 (10.8)

Mustillo et al. (2003)

991 youth in the general pediatric population

Age range: 9-16

38.6% of the participants scored at or above the cut-off of 36 on the WURS, signicantly higher than the 4% prevalence previously reported in a normal sample (p < 0.001); the inattention-memory, the impulsivity-emotionality, the DSM-IV-inattentive, and the ADHD-index subscales scores of the CAARS were signicantly higher than the expected frequency; 61% of the patients had scores at the Brown ADD Scale for Adults, suggestive of probable ADHD; 26.6% of the patients were classied as likely cases of ADHD (vs. DSM-IV adult prevalence estimates of 3-5%) The diagnosis of ADHD was not associated with any of the obesity trajectories (no obesity, childhood obesity, adolescent obesity, and chronic obesity).

Strengths: psychiatric comorbidities were controlled for Limitation: diagnosis of ADHD was not based on information obtained by multiple sources

Although a formal diagnosis of ADHD was not performed in this study, the authors used a questionnaire with high sensitivity to detect ADHD and combined data

from different questionnaires to classify the subjects as likely cases of ADHD. WURS: Wender Utah Rating Scale; CAARS: Adult ADHD Rating Scale.

528

S. CORTESE ET AL.

subscales scores did not signicantly differ from the reference norms. Sixty-one percent of the patients had scores higher than the 93rd percentile at the Brown ADD Scale for Adults, suggestive of probable ADHD. Finally, 26.6% of the patients were classied as likely cases of ADHD on the basis of the combination of a childhood history of ADHD, as indicated by an elevated WURS subscore (36), and two elevated CAARS symptom scales (T 65). This prevalence was well above the DSM-IV adult prevalence estimates of 35% (APA, 1994). Clearly, since these data were collected using the patients as the exclusive source of information and no formal diagnosis was obtained, the authors could not rule out the possibility that these symptoms may have been the expression of other psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, or sleep disorders. Moreover, all the patients in this study were women, preventing the generalizability of these ndings to men. All the above reviewed studies were conducted in clinical settings, and, therefore, their results may not reect the prevalence of ADHD in obese persons in the general population. It is of interest, therefore, to look at the prevalence of ADHD (diagnosed according to standardized criteria) in obese persons in the general population as reported in epidemiological surveys. In the only non-clinical study assessing the prevalence of ADHD in obese persons that we found, Mustillo et al. (2003) evaluated annually, over an 8-year period, the weight status and psychiatric disorders in a sample of 991 youths aged 916 years. On the basis of their weight status during the study period, participants were divided into four obesity trajectories: no obesity, childhood obesity, adolescent obesity, and chronic obesity (obesity was dened as BMI age- and sex- specic percentiles >95th according to the growth charts of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Kuczmarski et al., 2000)). The psychiatric assessment was performed using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) (Angold et al., 1999), which is an interviewer based interview with both the child and the parents and combines the advantages of clinical interviews with those of highly structured epidemiologic interview methods, providing a psychiatric diagnosis according to the DSM-IV criteria. While oppositional disorder was more common in chronically obese boys and girls than non obese group, the diagnosis of ADHD was not associated with any of the obesity trajectories. A major strength of this study is the measurement of a wide range of risk factors and correlates, including state-of-the-art assessment for psychiatric disorder. Moreover, the authors were able to control for the effect of psychiatric comorbidities. Given the high psychiatric comorbidity associated with ADHD, this seems of relevance in order to understand if the potential association between ADHD and obesity is true or is mediated by comorbid disorders (such as depressive disorders). However, the study also had some limitations. The diagnosis of ADHD in clinical settings is based on information obtained by multiple sources, such as teachers or other third persons, besides children and parents, and this is obviously difcult in a large survey such as this study. Moreover, as stated by the authors, their statistical model did not allow them to determine whether an association between

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

obesity and psychiatric disorders was more likely to occur at a particular age or if the association existed over time. In summary, we located four studies (Agranat-Meged et al., 2005; Altfas, 2002; Fleming et al., 2005; Erermis et al., 2004) conducted in clinical settings and one survey (Mustillo et al., 2003) in the general population. All the four studies provide empirically based evidence suggesting a higher than expected prevalence of ADHD in clinical obese subjects. On the other hand, the survey by Mustillo et al. (2003) in the general pediatric population found no association between ADHD and obesity. However, as correctly pointed out by Altfas (2002), clinical settings may favor a higher case-nding rate because the opportunity to observe and assess behavior is greater than the methods of epidemiological surveys. Therefore, the gold standard of careful clinical assessment is expected to nd more cases of a particular psychiatric disorder in comparison to the assessment used in surveys in the general population. This may explain, at least in part, the discordance in the results between the clinical studies (Agranat-Meged et al., 2005; Altfas, 2002; Fleming et al., 2005; Erermis et al., 2004) and the survey (Mustillo et al., 2003) reviewed here.

Studies Assessing the Weight Status of Subjects with ADHD (Table 2) Spencer et al. (1996) evaluated height and weight in a sample of 124 males with ADHD (diagnosed according to the DSMIII-R criteria) and 109 normal controls aged 617 years. Exclusion criteria were IQ less than 80, adopted and stepchildren, major sensorimotor handicaps (paralysis, deafness, blindness), psychosis, autism, suicidality, and mental retardation. Children from the lowest socioeconomic class were excluded to avoid the confounds of extreme social adversity. Eighty-nine per cent of subjects had received pharmacological treatment at some time in their lives, including stimulants. Fifty-three subjects had received stimulants (which may have anorexigenic effects) while 66 subjects did not receive any stimulant treatment in the past two years. The authors derived an age- and height-corrected weight index from standard growth tables (an index of 100 indicates that a subjects weight is the average expected weight for height and age; an index greater than 100 indicates greater than the average expected weight). ADHD probands were found to have greater than average body mass (age- and height-corrected weight index: 109 15), although no signicant difference was found between the age- and height-corrected weight index of ADHD and control subjects. Interestingly, age- and height-corrected weight index of untreated ADHD was 115, indicative of overweight. However, this result should be considered with caution given the limited number of untreated subjects (N = 13). This was a 4-year follow-up study and growth measures were obtained only at the follow-up assessment. Therefore, height and weight at baseline (before treatment) were not available. Given that some psychotropics may have anorexigenic effects, one cannot exclude that age- and height-corrected weight indices of

ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD) AND OBESITY

529

Table 2 Studies on the weight status of subjects with ADHD. Case reports, non empirical studies and studies not using standardized ADHD diagnostic criteria were excluded First author (year) Spencer et al. (1996) Subjects 124 males with ADHD and 109 normal controls Mean age (SD)/age range (years) Age range: 6-17 Key results ADHD subjects had greater than average body mass (age- and height-corrected weight index: 109 15), although no signicant difference was found between the age- and height-corrected weight index of ADHD and control subjects. Age- and height-corrected weight index of untreated ADHD was 115, indicative of overweight The age-and height-corrected weight index was greater than average (1.1), although not indicative of overweight or obesity. No signicant differences were found between ADHD girls and controls, as well as between treated and untreated subjects. ADHD girls with comorbid major depression (MD) had a signicantly greater average height- and age-corrected weight index relative to ADHD girls without MD ( p = .011) The mean BMI-SDS of ADHD patients were signicantly higher than the age-adapted reference values (p = 0.038). The proportion of obese (7.2%) and overweight (19.6%) participants was signicantly higher than estimated prevalence (p = 0.0008 and p = 0.0075, respectively). Comments

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

Biederman et al. (2003)

140 ADHD girls and 122 female controls

Age range: 617

Holtkamp et al. (2004)

97 inpatient and outpatient boys with ADHD in a Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Department

10 (2)

Curtin et al. (2005)

98 children with ADHD in a tertiary care clinic for developmental, behavioral and cognitive disorders

Age range: 318

Faraone et al. (2005)

568 children with ADHD enrolled in a study of the safety of mixed amphetamine salts

Age range: 612

Strength: children from the lowest socioeconomic class and children with major sensorimotor handicaps (paralysis, deafness, blindness), psychosis, autism, or suicidality were excluded Limitation: the impact of psychiatric co-morbid disorders and pharmacotherapy was not assessed Strengths: the authors controlled for the effect of co-morbid major depression and pharmacotherapy; children from the lowest socioeconomic class and children with major sensorimotor handicaps (paralysis, deafness, blindness), psychosis, autism, or suicidality were excluded Limitation: no information on duration, dose, or interruptions of stimulant treatment Strength: children with additional psychiatric (e.g. pervasive developmental disorder, psychosis, tics anxiety or mood disorder), somatic, or neurological disorders were excluded by medical history, physical examination, and EEG Limitations: lack of control group; socioeconomic status and BMI of parents were not controlled for 29% of children with ADHD were at Strength: children underwent a risk for overweight and 17.3% thorough physical, were overweight. No signicant neurological, and difference in comparison to an developmental examination age-matched reference population. Limitation: the effect of However, the prevalence of at risk psychiatric comorbidities and for overweight and overweight in medication other than children not treated with ADHD methylphenidate was not drugs (36% and 23%, respectively) controlled for was signicantly higher than that found in treated participants (16% and 6.3%, respectively) (p < 0.05) At baseline, subjects were heavier Strength: BMI z-scores were than average (mean BMI z-score calculated = 0.41) Limitations: the effect of comorbid psychiatric disorders was not controlled for; no data on the prevalence of obesity or overweight (Countinued on next page)

530

S. CORTESE ET AL.

Table 2 Studies on the weight status of subjects with ADHD. Case reports, non empirical studies and studies not using standardized ADHD diagnostic criteria were excluded. (Countinued) First author (year) Hubel et al. (2006) Subjects 39 boys with ADHD and 30 healthy controls Mean age (SD)/age range (years) Age range: 814 Key results BMI-SDS were higher in ADHD than in controls. No signicant association between group membership (control vs. ADHD) and obesity or overweight Subjects with ADHD had higher mean BMI z-scores at all ages compared with individuals who were not observed with a disruptive disorder Comments Strengths: BMI-SDS was calculated; exclusion criteria: stimulant treatment, endocrine, metabolic, physical, or other psychiatric disorders (except conduct disorders) Strength: BMI z-scores were calculated Limitations: diagnosis of ADHD was not based on information from third sources; the effect of comorbid psychiatric disorders (depression or anxiety) was not controlled for Strength: BMI z-scores were calculated Limitations: the effect of comorbid psychiatric disorders was not controlled for; no data on the prevalence of obesity or overweight Limitations: the effect of co-morbid psychiatric disorders was not controlled for; no data on the prevalence of obesity or overweight Strength: large sample size Limitations: no formal diagnosis of ADHD; the effect of comorbid psychiatric disorders was not controlled for

Anderson et al. (2006)

655 subjects (general population)

Younger than 16.6

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

Spencer et al. (2006)

178 children with ADHD receiving OROS methylphenidate

Age range: 613

Subjects were slightly overweight compared with that expected for their age (mean BMI z-score = 0.230)

Swanson et al. (2006)

140 children with ADHD

Age range: 35.5

The average BMI was 16.9, which corresponds to the 86th percentile at the baseline assessment Subjects with high ADHD tendency had an increased risk for obesity of 1.4 times as compared to subjects with low ADHD tendency

Lam and Yang (2007)

1429 students (general population)

Age range: 1317

untreated ADHD subjects might have been signicantly higher than controls at baseline. The authors did not report the impact of psychiatric comorbid disorders (such as depressive disorders) on the age- and height-corrected weight index. Using similar methodology, the same group (Biederman et al., 2003) compared weight and height in a sample of 140 ADHD girls and 122 female controls aged between 6 and 17 years. The age- and height-corrected weight index of ADHD subjects was greater than average (although not indicative of overweight or obesity) but no signicant differences were found between ADHD girls and controls, as well as between treated and untreated subjects. Interestingly, ADHD girls with comorbid major depression (MD) had a signicantly greater average height- and age-corrected weight index relative to ADHD girls without MD (with MD, N : 21: 126 31.3; without MD, N : 103: 109 25.7; p = .011). Of note, the average weight index of the ADHD children with comorbid MD was greater than the recommended cut-off for obesity (i.e. 120). In a study conducted in a Child Psychiatry Department, Holtkamp et al. (Holtkamp et al., 2004) found that the mean BMI-SDS of 97 inpatient and outpatient boys (aged 5.514.7 years), diagnosed with the combined DSM-IV type of ADHD,

was signicantly higher than the age-adapted reference values of the German population (Kromeyer-Hauschild et al., 2001) (p = 0.038). Moreover, the proportion of obese (7.2%) and overweight (19.6%) participants (dened as those with a BMI 97th and 90th percentile, respectively), was signicantly higher than the prevalence of obesity and overweight in the German population of the same age (p = 0.0008 and p = 0.0075, respectively). Of note, exclusion criteria were the use of orexigenic medications (other than methylphenidate) as well as somatic, neurologic, and psychiatric disorders (such as depression) which may have contributed to increase in the prevalence of overweight or obesity. The only psychiatric comorbid disorder was conduct disorder (57.7% of the participants); however, the authors found no signicant differences in the relative number of overweight and obese participants, as well as in the mean BMI standard deviation scores (SDS), between participants with and without conduct disorder. Moreover, although 14.4% of the patients were treated with methylphenidate (which may have anorexigenic effects) for a mean of ve months, there were no signicant differences between medicated and medication-free participants. As stated by the authors, the use of a clinical sample of boys only and the lack of control for factors such as socioeconomic status and BMI of parents represent limitations of the study. Moreover,

ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD) AND OBESITY

531

the protocol study did not include a control group: the mean BMI-SDS of the participants was compared to a reference population assessed several years earlier, raising the possibility that the results may have been due to an isolated trend in increasing obesity. However, Holtkamp et al. (2004) concluded that, after comparing recent BMI of the children from the area of the study to the reference population national norms, this isolated trend was unlikely. Curtin et al. (2005) performed a chart review of 98 children (aged 219 years) with ADHD (diagnosed according to DSMIV criteria) in a Child Psychopathology Unit. They found that 29% were at risk for overweight (BMI z-scores >85th percentile) and 17.3% were overweight (BMI z-scores >95th percentile); in the 25 year old group, prevalence of at risk for overweight was 42.9%. These estimates did not signicantly differ in comparison to an age-matched reference population (NHANES 1999 2002 (Flegal et al., 2002)). However, when the authors analyzed only the children not treated with stimulants (in order to control for the potential anorexigenic effects of these drugs), the prevalence of at risk for overweight and overweight was, respectively, 36% and 23%, differing signicantly from that found in treated participants (16% and 6.3%, respectively) (p < 0.05). Interestingly, none of the children taking stimulant medications were underweight (i.e., below the 15th percentile), although 16% of the children not receiving stimulant medications were underweight. Only small numbers of children with ADHD received other types of medications (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) n = 2; anticonvulsants n = 1; antihypertensives n = 7; other antidepressants n = 1; and other medications n = 5). Unfortunately, because of the small sample size, the authors were not able to examine these medications in relation to weight status. Moreover, they could not control for the effect of potential comorbid psychiatric disorders. More recently, Hubel et al. 2006) compared the mean BMISDS of 39 boys with ADHD and 30 healthy controls aged 814 years. All subjects were recruited in the local community. ADHD diagnoses were made according to the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria. Twenty-four ADHD children presented with the combined type and 15 with the predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type. None of the participants was taking medications or had taken stimulants in the previous two years. Moreover, none of the subjects had any endocrine, metabolic, physical, or other psychiatric disorders except conduct disorders. It was found that the BMI-SDS were higher in ADHD than in controls (0.29 1.01 and 0.05 0.94, respectively). Group differences were more pronounced in older children. No difference was found between the two ADHD groups. Interestingly, the results remained valid even when anxiety/depression symptoms and general psychic impairments were controlled for. Moreover, the proportions of obese and overweight subjects in the ADHD group (17.95% and 7.69%, respectively) were well comparable to those reported by Holtkamp et al. 2004). However, using chi (APA, 1994) analyses, the authors found no signicant association between group membership (control vs. ADHD) and obesity or overweight. Since differences in weight status between ADHD and control

subjects were more pronounced in adolescence and age effects were not accounted for in the chi (APA, 1994) analyses, the authors could not exclude an actually existing association between group membership and weight status in older subjects. Anderson et al. (2006) analyzed data from a prospective study on the determinants and correlates of psychiatric disorders in a sample of 655 subjects younger than 16.6 years. Psychiatric disorders were assessed with a structured diagnostic interview consistent with DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) criteria, administered separately, by trained lay interviewers, to the parents and the participants. BMI was calculated from reported weight and height. BMI z-scores were derived using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention BMI for-age reference (Ogden et al., 2002). Subjects with a disruptive disorder (including ADHD, ODD, and CD) before age 16.6 years had higher mean BMI z-scores at all ages compared with individuals who were not observed with a disruptive disorder. Mean BMI z-scores were 0.21 (95% CI, 0.070.35) units higher than individuals without a disruptive disorder. When ADHD, ODD, and CD were modeled separately, the pattern of results did not differ substantially. After excluding subjects using medications, the results did not change. One limitation of the study is that the authors did not control for the effect of potential comorbid disorders such as depressive or anxiety disorders. Moreover, as discussed for the study by Mustillo et al. (2003), given that this was a population survey, diagnoses could not be based on information from third sources (i.e. teachers or other relevant persons). In another larger population survey, Lam and Yang (2007) investigated the potential association between ADHD and overweight/obesity in a sample of 1429 students aged between 13 and 17 years. Structured interviews according to DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria were performed for the assessment of ADHD symptoms. However, given the intrinsic limitations of the study design and the number of the participants, structured interviews were administered to students only and no information was obtained from parents or teachers. Therefore, the authors were able to obtain an ADHD tendency more than a clinical diagnosis of ADHD. After adjusting for potential confounding factors including snoring, it was found that subjects with high ADHD tendency had an increased risk for obesity of 1.4 times as compared to subjects with low ADHD tendency. As in other above discussed studies, the authors did not control for the effect of potential comorbid psychiatric disorders. Three studies (Faraone et al., 2005; Spencer et al., 2006; Swanson et al., 2006) investigating the growth effects of stimulants in ADHD children found, at baseline, a mean BMI z-score >0, indicating that ADHD subjects were heavier than expected. However, these studies did not provide data on the prevalence of obesity in children with ADHD, as well as of psychiatric comorbid disorders (such as depressive disorders) which may impact body mass. In summary, data from literature indicate that children with ADHD have a higher than expected BMI. However, evidence suggesting an increased prevalence of obesity in subjects with ADHD is still limited and inconsistent. Moreover, the impact of

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

532

S. CORTESE ET AL.

psychiatric comorbidity on body mass has not been systematically addressed in the above reviewed studies.

Systematic Review: Conclusion After excluding case reports, descriptive studies with no statistical analyses of data and studies which measured simple symptoms of ADHD without using diagnostic criteria, empirically based evidence suggests that obese patients referred to obesity clinics may present with higher than expected prevalence of ADHD. Moreover, all reviewed studies indicated that subjects with ADHD are heavier than expected. However, data on the prevalence of obesity in subjects with ADHD are still limited. Anyway, even if the comorbidity between ADHD and obesity held true in clinical samples only, it would still have relevant implications for the clinical presentation and the management of these patients, and so we believe that it is noteworthy. In the next section, we will examine the potential mechanisms that have been proposed for this possible comorbidity, in order to better understand the potential implications on the management of patients with both ADHD and obesity, which will be the subject of the third section of this review. POTENTIAL MECHANISMS UNDERLYING THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN ADHD AND OBESITY Since the above-reviewed studies, pointing to an association between obesity and ADHD, are cross-sectional, they do not allow an understanding of the causality between ADHD and obesity. From a theoretical point of view, we think that the results of our systematic review allow for the consideration of the following hypotheses: 1) obesity or factors associated with obesity lead to or manifest as ADHD symptoms; 2) ADHD and obesity are the expression of a common biological dysfunction that manifests itself as obesity and ADHD in a subset of patients who present with both of these conditions; 3) ADHD contributes to obesity. 1) The rst hypothesis is that obesity or factors associated with obesity lead to or manifest as ADHD. Recently, Rosval et al. (2006) reported higher rates of motoric impulsiveness in patients with bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa binge/purge subtype in comparison to anorexia nervosa, restricting subtype and normal eater control group, conrming the previous ndings linking binge eating behaviors with behavioral impulsivity (Engel et al., 2005; Nasser et al., 2004). Since binge eating behaviors may be present in obese patients (especially in those with severe obesity) (Hudson et al., 2006), it is possible that impulsivity associated with these abnormal eating behaviors contributes to or manifests as impulsivity of ADHD in these patients. It is also possible that impulsivity associated with abnormal eating behaviors fosters symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity. Clinicians report that patients with

bulimic or abnormal eating behaviors may present with repeated and impulsive interruptions of their activities in order to get food, resulting in ADHD symptoms such as disorganization, inattention, and restlessness (Cortese et al., 2007). Other unexplored hypotheses deserve further investigation. For example, there is some evidence that sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) may lead to ADHD or to ADHD symptoms (Chervin et al., 2005). It has been hypothesized that hypoxia or sleep fragmentation arousals associated with apnea and hypopneas contribute to ADHD. Since obesity is associated with SDB (Gami et al., 2003), it is possible that obesity leads to ADHD/ADHD symptoms via SDB, at least in a subset of patients. 2) Another possibility is that obesity and ADHD are different expressions of common underlying biological mechanisms. Therefore, ADHD and obesity might share common biological underpinnings at least in a subset of patients with both these conditions. Bazar et al. (2006) speculated on some possible common mechanisms, including the reward deciency syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by an insufcient dopamine-related natural reward that leads to the use of unnatural immediate rewards, such as substance use, gambling, risk taking, and inappropriate eating. Several lines of evidence suggest that patients with ADHD may present with behaviors consistent with the reward deciency syndrome (Gami et al., 2003; Blum et al., 1995, 2000; Heiligenstein and Keeling, 1995). This syndrome has been reported also in obese patients with abnormal eating behaviors (Comings and Blum, 2000). Alterations in the dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) (Bazar et al., 2006) and, to a lesser extent, DRD4 (Mitsuyasu et al., 2001; Tsai et al., 2004) have been associated with the above-mentioned reward deciency syndrome. Dysfunctions of DRD2 and DRD4 have been found in obese patients (Noble, 2003; Poston et al., 1998). Several studies suggest a role of altered DRD4 and DRD2 in ADHD as well (although the alteration in DRD2 has not been replicated in other studies) (Noble, 2003; Bobb et al., 2005). Therefore, obese patients with abnormal eating behaviors and ADHD may present with common genetically determined dysfunctions in the dopaminergic system. Interestingly, in a study by Levitan et al. (2004) on a sample of women with seasonal affective disorder (SAD), the 7R allele of DRD4 was associated with signicantly higher scores of childhood inattention on the WURS-25 and with significantly higher maximal lifetime BMI. SAD is characterized by marked craving for high-carbohydrate/high-fat foods, resulting in signicant weight gain during winter depressive episodes. A potential implication of the reward system in the pathophysiology of the disorder has been suggested. Therefore, Levitan et al. (2004) hypothesized that childhood attention decit and adult obesity may be the expression of a common biological dysfunction of the 7R allele of DRD4 associated with a dopamine dysfunction in prefrontal attentional areas and brain circuits involved in the reward pathways.

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD) AND OBESITY

533

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

However, these authors did not consider a formal diagnosis of ADHD according to standardized criteria. Another potential common biological mechanism involves alterations in the Brain Derived Neurotropic Factor (BDNF). Preliminary evidence from animal model studies points to a potential dysfunction of BDNF underlying both ADHD and obesity (Lyons et al., 1999; Kernie et al., 2000; Rios et al., 2001). However, a recent study by Friedel et al. (2005) in humans does not suggest a large role of genetic variation of BDNF in ADHD and obesity. On the other hand, recently Gray et al. (2006) found a functional loss of one copy of the BDNF gene in an 8-year old with hyperphagia, severe obesity, impaired cognitive function, and hyperactivity. Therefore, given the limited and inconsistent ndings, the role of common genetic mutations underlying shared neurobiological dysfunctions in ADHD and obesity deserves further investigation. Clearly, a bidirectional rather than unidirectional relationship between obesity and ADHD would suggest stronger evidence for common mechanisms between the two. 3) Our systematic review indicates that subjects with ADHD present with higher than expected body mass. This may support the hypothesis that ADHD actually contributes to obesity. Abnormal eating behaviors associated with ADHD may play a signicant role. Altfas (2002) reported that, in his experience, impulsive eating behaviors are common in adult and adolescent patients with both ADHD and obesity. According to clinical observations of Curtin et al. (2005), children with ADHD may be at increased risk for overweight due to their unusual dietary patterns. In a study (Mattos et al., 2004) of a clinical sample of 86 Brazilian adult patients with ADHD (DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria), the prevalence of Binge Eating Disorder was 8.13%, which is higher than the estimate in the general population (2.6%). The authors correctly point out that, since only two DSM-IV criteria for BED involve impulsivity or its correlates, ADHD impulsivity per se would not be enough for a BED diagnosis, suggesting a true comorbidity. However, only two participants with BED were overweight and none were obese. This, according to the authors, is atypical, since, as they stated, although weight is not part of BED criteria, this is a very common feature. In a study on 110 adult healthy women (age range: 2546 years), Davis et al. (2006), using structural equation modelling, found that ADHD symptoms and impulsivity were signicantly correlated with abnormal eating behaviors, including binge eating and emotionally-induced eating, which, in turn, were positively associated with BMI. In a recent analysis of 4 case-controls studies, Surman et al. (2006) found signicantly greater rates of bulimia nervosa in women with versus without ADHD, but not in men or children; however, the mean BMI of the patients with bulimia was not reported in this paper. In another recent study of a clinical sample of 99 severely obese adolescents (aged 1217 years), Cortese et al. (2007) found that, after controlling for potentially con-

founding depressive and anxiety symptoms, ADHD symptoms, measured by the ADHD-index score of the Conners Parents Rating Scale (CPRS) (Conners, 1969), were signicantly associated with bulimic behaviors. At the present time, it is not clear which dimension of ADHD (inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity) may specically be associated with abnormal eating behaviors. The results of Cortese et al. (2007), i.e. signicant association between bulimic behaviors and ADHD-index score (which measures symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity) and lack of signicant association between bulimic behaviors and CPRShyperactivity-impulsivity index (which contains only one item of impulsivity) led the authors to speculate that both a) impulsivity and b) inattention might lead or contribute to abnormal eating behaviors, whereas hyperactivity would not play a significant role. a) As for impulsivity, Davis et al. (2006) suggested that both decient inhibitory control and delay aversion, which are expression of the impulsivity component of ADHD, may foster abnormal eating behaviors, which, interestingly, correlated to patients BMI in their study. Decient inhibitory control, which manifests itself as poor planning and a difculty to monitor ones behavior effectively, could lead to overconsumption when not hungry associated with the relative absence of concern for daily caloric intake. A strong delay aversion could favor the tendency to eat high caloric content fast food in preference to less caloric content home-cooked meals (which take longer to prepare). This may contribute to maintain a chronic positive energy balance, associated with obesity. Interestingly, several studies showed that obese subjects employ less effective strategies than non obese subjects on delay gratication tasks (especially with edible incentive) (Bonato and Boland, 1983; Bourget and White, 1984; Johnson et al., 1978; Sigal and Adler, 1976). This might contribute to overweight. b) It is also possible that inattention and decits in executive functions (which, as stated in the introduction, are frequently associated with ADHD), cause difculties in adhering to a regular eating pattern, favoring abnormal eating behaviors. Davis et al. (2006) pointed out that patients with ADHD may be relatively inattentive to internal signs of hunger and satiety. Therefore, they may forget about eating when they are engaged in interesting activities and they may be more likely to eat when less stimulated, at which point they may be very hungry. In the study of Altfas (2002), all obese participants with ADHD were diagnosed with the predominantly inattentive type of ADHD and they had more difculty losing weight, despite a signicantly higher number of visits, and a trend toward a longer duration of treatment than non ADHD patients. This kind of inefciency (taking more time to accomplish less) may be linked to attentional and organizational difculties. In line with this hypothesis, two recent studies (Beutel et al., 2006; Gunstad et al., 2007) reported

534

S. CORTESE ET AL.

poorer executive function test performance in obese vs. normal weight subjects. Another explication on the association between inattention and obesity was provided by Schweickert et al. (1997). According to these authors, compulsive eating may be a compensatory mechanism to help the person control the frustration associated with attentional and organizational difculties. Finally, Levitan et al. (2004) hypothesized that difculties initiating activities linked to attentional and organizational difculties contribute to decreased caloric expenditure, leading to weight gain over time. One can not exclude that all of the three above hypotheses may hold true and may co-exist, at least in certain subjects.

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH ADHD AND OBESITY From a clinical standpoint, the results of our systematic review suggest that it may be useful 1) to screen for ADHD in patients with obesity and 2) to look for abnormal eating behaviors in patients with ADHD. 1) As pointed out by Agranat-Meged et al. (2005), obesity may mask hyperactivity since obese individuals are less mobile. Therefore, clinicians may overlook the need of looking at ADHD in obese patients. However, screening for ADHD in patients with obesity may be of relevance for two reasons. First, as Altfas (2002) rst noted, obese patients with ADHD may have difculties in weight loss. Therefore, the management of ADHD might improve the management of obesity itself. Second, screening for and treating ADHD in obese patients, independently from associated abnormal eating behaviors, is relevant in light of the personal and social burden that ADHD adds to the already impairing condition of obesity. 2) Well known comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety or conduct disorders, are frequently investigated in clinical practice with ADHD patients. Recent works (Mattos et al., 2004; Surman et al., 2006) suggest that abnormal eating behaviors such as BED and bulimia, which are generally poorly investigated in patients with ADHD, should be screened as well. These abnormal eating behaviors may further impact the quality of life of these patients and might contribute to obesity. Therefore, the subset of obese patients with abnormal eating behaviors and ADHD should be considered a group particularly at risk and meritorious of appropriate management. With regard to the therapeutic strategies, if the hypothesis that ADHD actually contributes to obesity is true, then the treatment of ADHD might improve obesity. Several reports (Schweickert et al., 1997; Sokol et al., 1999) have suggested that stimulants improve ADHD and abnormal eating behaviors in patients

with both conditions. Surman et al. (2006) explained the ndings of these reports suggesting that the treatment of ADHDrelated impulsivity could improve abnormal eating behaviors. Improvement in attention, leading to more regular eating patterns, may also play a signicant role. However, none of these reports specically analyzed obese participants, so evidence that improvements in eating behaviors due to ADHD treatment lead to a weight loss in obese patients with ADHD is still missing. Indeed, these reports also support the hypothesis that ADHD and abnormal eating behaviors share common underlying biological mechanisms, which may be the target of ADHD medications, or that ADHD medications act both on the brain pathways involved in ADHD and on those that mediate abnormal eating behaviors. Meredith et al. (2002) found that repeated injections of amphetamine were accompanied by an elevated BDNF mRNA and BDNF immunoreactivity in the basolateral amygdala, rostral piriform cortex, and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Since there is some evidence that reduction of BDNF in the hypothalamus causes increased locomotor activity and eating behaviors (Kernie et al., 2000), the nding of Merendith et al. (2002) supports the hypothesis that ADHD medications may also act on brain pathways involved in eating behaviors. Moreover, Gadde et al. (2006) published a trial on the efcacy of atomoxetine, the second-line medication of ADHD, in weight reduction in obese women. The positive results of the trial suggested that this ADHD drug may act on the noradrenergic synapses in the medial and paraventricular hypothalamus that are thought to play a major role in modulating satiety and feeding behavior. These preliminary observations suggests that in patients with ADHD and abnormal eating behaviors (associated with obesity), both conditions might improve using the same class of agents. This is particular important considering that other agents (SSRIs, which are not highly effective in patients with ADHD) represent the usual pharmacological treatment for abnormal eating disorders. To our knowledge, at the present time, there are no controlled studies on the impact of non- pharmacological treatment of ADHD on weight reduction. Since it is possible that an improvement in the attentional and organizational strategies leads to a decrease in abnormal eating behaviors resulting in a weight loss, research in this eld should be particularly encouraged, as well as studies assessing the effectiveness of the combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of ADHD on weight loss in obese patients. On the other hand, we are not aware of any studies assessing the impact of the treatment of binge eating on ADHD symptoms in patients with ADHD and abnormal eating behaviors. We think that such studies should be encouraged. CONCLUSION Clinicians have generally overlooked the potential association between ADHD and obesity, possibly because hyperactivity (the most evident but not necessarily the most signicant

ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD) AND OBESITY

535

symptom of ADHD) may be masked by obesity. However, empirically based evidence from recent literature points to a possible comorbidity between ADHD and obesity, at least in clinical samples of obese patients. Data on the prevalence of obesity in ADHD patients are still limited. More methodologically sound studies, using standardized diagnoses of ADHD and homogeneous denitions of obesity/overweight, as well as controlling for potential confounding factors (such as socioeconomic status) and psychiatric comorbid disorders (such as depressive and anxiety disorders) are greatly needed. However, even if the association between ADHD and obesity held true only in obese patients treated in specialized clinics, it would still be noteworthy since this is the class having the highest mortality and morbidity risk and the greatest need for effective treatment. Given that the management of ADHD might improve eating behaviors, screening for ADHD in these patients may be of clinical relevance. Since it has been shown that reduction of body weight as small as 5% substantially reduces the morbidity and mortality risks of obesity (Altfas, 2002), even if ADHD only modestly impacted weight status, such screening may be relevant. On the other hand, screening for overlooked abnormal eating behaviors may improve the symptoms and the quality of life of patients with ADHD and may potentially prevent weight gain which would add a further burden to these patients. Prospective studies, at present still lacking, could lead to a better understanding of the causality in the relationship between ADHD and obesity, shading light into the psychopathological pathways linking the two conditions. Family studies examining the occurrence of ADHD and obesity and further animal model studies are necessary to gain insight into the potential common genetic underpinnings. Finally, pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment studies are greatly needed to nd more appropriate and effective therapeutic strategies for patients with both obesity and ADHD. Therefore, clinical empirically based studies, epidemiological surveys (both cross-sectional and prospective), genetic studies, animal model studies, non-pharmacological treatment studies, and pharmacological trials should be highly encouraged since they may advance the knowledge in the eld, allowing for better management, and ultimately, a better quality of life for patients with both obesity and ADHD.

REFERENCES

Agranat-Meged, A. N. et al. (2005). Childhood obesity and attention decit/hyperactivity disorder: a newly described comorbidity in obese hospitalized children. Int. J. Eat. Disord, 37:357359. Altfas, J. R. (2002). Prevalence of attention decit/hyperactivity disorder among adults in obesity treatment. BMC. Psychiatry, 2:9. American Psychiatric Association (1952). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-I. Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Association (1968). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-II. Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Association (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC.

American Psychiatric Association (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. revised. Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text Revision. Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Association ed. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC. Anderson, S. E. et al. (2006). Relationship of childhood behavior disorders to weight gain from childhood into adulthood. Ambul. Pediatr, 6:297301. Angold, A. et al. (1999). Interviewer-based interviews. In: Diagnostic Assessment in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. (Shaffer D, L. C. R. J., ed), 3464. Bazar, K. A. et al. (2006). Obesity and ADHD may represent different manifestations of a common environmental oversampling syndrome: a model for revealing mechanistic overlap among cognitive, metabolic, and inammatory disorders. Med. Hypotheses, 66:263269. Beutel, M. E. et al. (2006). Attention and executive functions in patients with severe obesity : A controlled study using the Attention Network Test. Nervenarzt, 77:13231331. Biederman, J. (2005). Attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder: a selective overview. Biol. Psychiatry, 57:12151220. Biederman, J. and Faraone, S. V. (2005). Attention-decit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet, 366:237248. Biederman, J. et al. (2003). Growth decits and attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder revisited: impact of gender, development, and treatment. Pediatrics, 111:10101016. Blum, K. et al. (1995). Dopamine D2 receptor gene variants: association and linkage studies in impulsive-addictive-compulsive behaviour. Pharmacogenetics, 5:121141. Blum, K. et al. (2000). Reward deciency syndrome: a biogenetic model for the diagnosis and treatment of impulsive, addictive, and compulsive behaviors. J. Psychoactive Drugs, 32 Suppl, 1112. Bobb, A. J. et al. (2005). Molecular genetic studies of ADHD: 1991 to 2004. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet, 132:109125. Bonato, D. P. and Boland, F. J. (1983). Delay of gratication in obese children. Addict. Behav. 8:7174. Bourget, V. and White, D. R. (1984). Performance of overweight and normalweight girls on delay of gratication tasks. Int. J. Eat Disord. 3:6371. Brown T. E. (1996). Brown Attention-Decit Disorder Scales. Harcourt Brace & Company, New York. Carey, W. B. et al. (1988). Temperamental factors associated with rapid weight gain and obesity in middle childhood. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 9:194 198. Chervin, R. D. et al. (2005). Snoring predicts hyperactivity four years later. Sleep, 28:885890. Comings, D. E. and Blum, K. (2000). Reward deciency syndrome: genetic aspects of behavioral disorders. Prog. Brain Res. 126:325341. Conners C. K. et al.(1999). Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS)., Canada, Multi-Health Systems Inc. Conners, C. K. (1969). A teacher rating scale for use in drug studies with children. Am. J. Psychiatry, 126:884888. Cortese, S. et al. (2007). Association between symptoms of attentiondecit/hyperactivity disorder and bulimic behaviors in a clinical sample of severely obese adolescents. Int. J Obes. (Lond), 31:340346. Curtin, C. et al. (2005). Prevalence of overweight in children and adolescents with attention decit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorders: a chart review. BMC. Pediatr. 5:48. Davis, C. et al. (2006). Associations among overeating, overweight, and attention decit/hyperactivity disorder: A structural equation modelling approach. Eat Behav. 7:266274. Dietz, W. H. and Robinson, T. N. (2005). Clinical practice. Overweight children and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:21002109. Drimmer, E. J. (2003). Stimulant treatment of bulimia nervosa with and without attention-decit disorder: three case reports. Nutrition, 19:7677. Dukarm C. P. (2005). Bulimia nervosa and attention decit hyperactivity disorder: a possible role for stimulant medication. J. Womens Health (Larchmt), 14:345350.

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012

536

S. CORTESE ET AL.

Dulcan, M. (1997). Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 36:85S121S. Engel, S. G. et al. (2005). Impulsivity and compulsivity in bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 38:244251. Erermis, S. et al. (2004). Is obesity a risk factor for psychopathology among adolescents? Pediatr. Int. 46:296301. Faraone, S. V. et al. (2005). Long-term effects of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts treatment of attention- decit/hyperactivity disorder on growth. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 15:191202. Flegal, K. M. et al. (2002). Weight-for-stature compared with body mass indexfor-age growth charts for the United States from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 75:761766. Fleming, J. P. et al. (2005). Symptoms of attention decit hyperactivity disorder in severely obese women. Eat Weight. Disord. 10:e10e13. Friedel, S. et al. (2005). Mutation screen of the brain derived neurotrophic factor gene (BDNF): identication of several genetic variants and association studies in patients with obesity, eating disorders, and attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 132:9699. Gadde, K. M. et al. (2006). Atomoxetine for weight reduction in obese women: a preliminary randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 30:11381142. Gami, A. S. et al. (2003). Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 32:869894. Gray, J. et al. (2006). Hyperphagia, severe obesity, impaired cognitive function, and hyperactivity associated with functional loss of one copy of the brainderived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene. Diabetes, 55:33663371. Gunstad, J. et al. (2007). Elevated body mass index is associated with executive dysfunction in otherwise healthy adults. Compr. Psychiatry, 48:5761. Heiligenstein, E. and Keeling, R. P. (1995). Presentation of unrecognized attention decit hyperactivity disorder in college students.J. Am. Coll. Health, 43:226228. Hellgren, L. et al. (1993). Children with decits in attention, motor control and perception (DAMP) almost grown up: general health at 16 years. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 35:881892. Holtkamp, K. et al. (2004). Overweight and obesity in children with AttentionDecit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 28:685 689. Hubel, R et al. (2006). Overweight and basal metabolic rate in boys with attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder. Eat. Weight. Disord. 11:139146. Hudson, J. I. et al. (2006). Binge-eating disorder as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 63:313319. Hwang, J. W. et al. (2006). The relationship between temperament and character and psychopathology in community children with overweight. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 27:1824. Johnson, W. G. et al. (1978). The performance of obese and normal size children on a delay of gratication task. Addict. Behav. 3:205208. Kaufman, J. et al. (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 36:980 988. Kernie, S. G. et al. (2000). BDNF regulates eating behavior and locomotor activity in mice. EMBO J. 19:12901300. Kessler, R. C. et al. (2005). Patterns and predictors of attentiondecit/hyperactivity disorder persistence into adulthood: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol. Psychiatry, 57:14421451. Kromeyer-Hauschild, K. et al. (2001). Percentiles of body mass index in children and adolescents evaluated from different regional German studies. Monatsschr. Kinderheilk, 149:807818. Kuczmarski, R. J. et al. (2000). CDC Growth Charts. United States. Adv. Data, 127. Lam, L. T. and Yang, L. (2007). Overweight/obesity and attention decit and hyperactivity disorder tendency among adolescents in China. Int. J. Obes. (Lond), in press. Levitan, R. D. et al. (2004). Childhood inattention and dysphoria and adult obesity associated with the dopamine D4 receptor gene in overeating

women with seasonal affective disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 29:179 186. Lumeng, J. C. et al. (2003). Association between clinically meaningful behavior problems and overweight in children. Pediatrics, 112:11381145. Lyons, W. E. et al. (1999). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-decient mice develop aggressiveness and hyperphagia in conjunction with brain serotonergic abnormalities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:1523915244. Malecka-Tendera, E. and Mazur, A. (2006). Childhood obesity: a pandemic of the twenty-rst century. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 30 Suppl 2:S1S3. Mattos, P. et al. (2004). Comorbid eating disorders in a Brazilian attentiondecit/hyperactivity disorder adult clinical sample. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 26:248250. McGee, R. et al. (1985). Physical development of hyperactive boys. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 27:364368. Meredith, G. E. et al. (2002). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression is increased in the rat amygdala, piriform cortex and hypothalamus following repeated amphetamine administration. Brain Res. 949:218227. Mitsuyasu, H. et al. (2001). Association analysis of polymorphisms in the upstream region of the human dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4) with schizophrenia and personality traits. J. Hum. Genet. 46:2631. Mustillo, S. et al. (2003). Obesity and psychiatric disorder: developmental trajectories. Pediatrics. 111:851859. Nasser, J. A. et al. (2004). Impulsivity and test meal intake in obese binge eating women. Appetite, 43:303307. Noble, E. P. (2003). D2 dopamine receptor gene in psychiatric and neurologic disorders and its phenotypes. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 116:103125. Ogden, C. L. et al. (2002). Kuczmarski, R. L., Flegal, K. M. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 109:60. Pliszka, S. R. et al. (2006). The Texas Childrens Medication Algorithm Project: revision of the algorithm for pharmacotherapy of attentiondecit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 45:642657. Poston, W. S. et al. (1998). D4 dopamine receptor gene exon III polymorphism and obesity risk. Eat Weight. Disord. 3:7177. Rios, M. et al. (2001). Conditional deletion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the postnatal brain leads to obesity and hyperactivity. Mol. Endocrinol. 15:17481757. Rojo, L. et al. (2006). Comorbidity between obesity and attention decit/hyperactivity disorder: Population study with 1315-year-olds. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 3:519522. Rosval, L. et al. (2006). Impulsivity in women with eating disorders: Problem of response inhibition, planning, or attention? Int. J Eat Disord. 39:590593. Sawyer, M. G. et al. (2006). Is there a relationship between overweight and obesity and mental health problems in 4- to 5-year-old Australian children? Ambul. Pediatr. 6:306311. Schweickert, L. A. et al. (1997). Efcacy of methylphenidate in bulimia nervosa comorbid with attention-decit hyperactivity disorder: a case report. Int. J. Eat Disord. 21:299301. Sigal, J. J. and Adler, L. (1976). Motivational effects of hunger on time estimation and delay of gratication in obese and nonobese boys. J. Genet. Psychol. 128:716. Sokol, M. S. et al. (1999). Methylphenidate treatment for bulimia nervosa associated with a cluster B personality disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 25:233237. Speiser, P. W. et al. (2005). Childhood obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90:18711887. Spencer, T. J. et al. (1996). Growth decits in ADHD children revisited: evidence for disorder-associated growth delays? J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry, 35:14601469. Spencer, T. J. et al. (2006). Does prolonged therapy with a long-acting stimulant suppress growth in children with ADHD? J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry, 45:527537. Strauss, C. C. et al. (1985). Personal and interpersonal characteristics associated with childhood obesity. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 10:337343.

Downloaded by [Columbia University] at 14:43 18 May 2012