Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Systems Checkland

Încărcat de

ScrbertoDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Systems Checkland

Încărcat de

ScrbertoDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

i -. .:.

In t c rna t ion a I En c y c I o p c d i a of

IJusincss and I\'1anagerncnt

Systems

1 The origins of systems thinking

2 The nature of systems thinking

3 The evolution of the systems movement

in the field of management

4 Varieties of systems thinking

5 The future of systems thinking

Overview

Tfie word 'system' is always taken to refer to a

\___.!t of elements joined together to make a

complex whole. The word may be used to refer

to an abstract whole (the principles constitut-

ing a system of justice, say,) or a physical whole

(a railway engine); but in both cases the

justification for using the word is the same:

the whole is seen as having properties which

make it 'more than the sum of its parts'.This is

the everyday-language expression of the idea

of so-called 'emergent properties', that is to

say properties which have no meaning in terms

of the parts_ which make up the whole. Thus, a

heap consisting of the individual parts of a

bicycle does not have vehicular potentiaL

However, when the parts are linked together

' '-../I a particular structure to make the bicycle as

a whole, which does have the potential to get

someone with the ability to ride from A to B,

that is an emergent property of the bicycle as a

whole .

. The idea of emergent properties is the single

most fundamental-systems idea and to use this

(and other) systems ideas in a conscious

organized way is to do some 'systems think-

ing'. To use systems thinking to tackle some

perceived problem is to take 'a systems ap-

proach' to it. Since the field of management

4742

deals with complex matters, and systems

thinking has been developed to cope with

complexity, it is not surprising to find systems

thinking closely associated with the field.

Indeed, many systems ideas and several ver-

sions of both systems thinking and a systems

approach have all been in work on

management problems. '

This entry will briefly review the origin and

nature of systems thinking and describe a

number of varieties of it as they have been

developed to tackle problems in the manage-

ment field.

1 The origins of systems thinking

Around the turn of the century, when biolo-

gists were considering the fundamental nature

of their science, a school of thourht arose

. -

which argued that biology's object of concern

was the living organism as a whole. It was

suggested by these 'organismic' biologists that

the science should develop by creating descrip-

tions of the basic processes which characterize

a living organism, processes of growth and

decay and so on. They developed the concept

of an organism as an 'open' entity which

exchanges materials, energy and information

with an environment to which it can adapt (a

metaphor which has been much taken up in

organization theory). Starting in the 1940s

Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1968) argued that the

ideas about organisms which he and his

colleagues had developed could in fact be

applied to wholes of any kind: to 'systems' in

general. This initiated systems thinking in a

formal sense.and in 1954 the first institution in

this new field was set up. This was the Society

for General Systems Research (SGSR), com-

mitted to the development of a General

System(s) Theory (GST) which could be

applied within any field in which phenomena

concerned with organized complexity were

studied. The pioneers hoped that communica-

tions between different scientific fields would

be helped by such theory.

These aspirations of the pioneers have not

been fulfilled; rather, systems thinking has

been developed within particular fields -

although the outcomes continue to provide,

in systems ideas, a language applicable within

many different disciplines. This means that as

.'ield, systems has the same status as Il!athe-

matics: it is a meta-discipline, a language,

which can be used to talk about the subject

matter of other areas. Thus, for example, there

are systems thinking geographers, sociologists

and management scientists, and other geogra-

phers, sociologists and management scientists

who do not use the systems language (see

ORGANIZATION BEHAVIOUR. HISTo'RY OF).

2 The nature of systems thinking

Throughout the systems literature the core

image upon which systems thinking is based is

that of the adaptive whole. The concept is of

some whole entity (which may be seen as a

whole because it has emergent properties)

-xisting in an environment which may change

.nd so deliver shocks to it. The adaptive whole

may then survive in the changing environment

if it can adapt to the changes.

Ordinary everyday experience offers many

examples of this process, which is what makes

systems thinking intuitively attractive. Thus,

when the temperature of our environment

rises, our bodies open pores and produce

sweat which evaporates and helps to cool us

down; the Boy Scouts movement survives for a

hundred years, but is not the same organiza-

. tion its founder created: it has adapted to a

changing society; manufactl,lring companies

using oil as a raw material had to change their

policies and operations very rapidly when the

price of oil increased fourfold between 1973

and 1974 and then doubled again in 1979, if

they were to survive in their changed economic

Systems

environment. All these happenings can be

expressed in systems language. They represent

the behaviour of entities which may be treated

as adaptive wholes.

In order to describe something as an adap-

tive whole, four fundamental ideas are needed.

First, the whole will be seen as ;1 system (rather

than simply as an aggregate) if an observer of it

can identify some emergent properties of it as

an entity. Second, the whole system may

contain parts which are themselves smaller

wholes (or 'sub-systems'). Thus, the human

body can be regarded as a system but also

within it sub-systems such as the respiratory

system or the blood-circulation system can be

identified. This means that systems thinking

postulates a layered or hierarchical structure

in which systems, part of wider systems, may

themselves contain sub-systems, which may

contain sub-sub-systems, and so on. Finally, if

a system is to survive in a changing environ-

ment it must have available to it processes of

communication and processes of control. It

must be able to sense the change in the

environment and adopt a suitable response

in the form of some so-called 'control action'.

In our bodies many such actions are auto-

matic, as when our core temperature is main-

tained within quite narrow limits. In designed

systems, engineers have to create mechanisms

which keep performance within chosen limits,

Watt's governor controlling the speed of a

steam engine being the paradigm example.

With the four concepts of emergent proper-

ties, a layered structure and processes of

communication and control a very wide range

of wholes may be described as systems capable

(within limits) of surviving in a changing

environment. Systems thinking applies these

ideas to a wide range of observed features of

the world, the purpose being, in general, either

to understand the world better or to intervene

to improve some part of it.

Three broad categories of work can be seen

in which the idea of an adaptive whole has

been developed and exploited. Biologists and,

especially, ecologists study the wholes that

nature creates, which are often referred to as

'natural systems', for example, frogs, forests,

the biosphere of the planet. Engineers, on the

other hand, create 'designed systems', systems

4743

Systems

planned to exhibit some desirable emergent

properties and to survive under a range of

environmental conditions. Note also that de-

signed systems may be abstract rather than

concrete, as in systems of philosophy or a set

of connected principles (as in, say, a 'design

philosophy' ).

It is the third broad area of systems think-

ing, however, which is of greatest interest to

those studying the problems of management.

For example, it was realized in the 1970s, in

action research which tackled messy real-

world problem situations, that a connected

set of human activities, joined together to

make a purposeful whole could, with the

addition of a monitoring and control sub-

system, be treated as a new kind of system

(Checkland 1981). Models of such systems

can be built and used to explore real-world

purposeful action. This yields a wide-ranging

approach to the problems within and between

organizations, since the taking of purposeful

action is a ubiquitous characteristic of human

affairs at many different levels, from the short-

term tactical to the long-term strategic and

over many time-scales.

These three broad categories of work are all

similar in that they exhibit the key--character-

istic of systems thinking, namely the conscious

use of systems concepts, especially that of the

adaptive whole, to understand some phenom-

ena in the world or to guide intervention

aimed at improvement. In more technical

language, systems ideas provide an epistemol-

ogy within which what counts as knowledge

for the systems thinker will be defined.

3 The evolution of the systems

movement in the field of

management

The systems movement has evolved steadily

since the late 1940s when GST emerged. In the

1950s much of the work done was of a

practical kind and represented the application

to civilian situations of the lessons learned

from the development of operations research

(OR) during the second world war (see OPERA-

TIONS RESEARCH).

The application of the lessons learned in

wartime OR to post-war activity in industrial

4744

and other organizations led to a number of

organized forms of.inquiry and problem sol-

ving. Bell Telephone Laboratories, for exam-

ple, formalized their approach to new-

technology projects in ' systems engineering'

(Hall 1962); the RAND Corporation devel-

oped 'systems analysis' (Optner 1973); and

when the first mainframe computers became

available the analysis needed to design and

establish a computer system drew on the same

set of ideas (see SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND DESIGN r

This was the dominant systems thinking in

management in the 1950s and 1960s. Its .

essence was to define very carefully a desirable

objective or need, to examine possible alter-

native systems which might achieve the objec-

tive or meet the need, and to select among the

alternatives, paying great attention to formu-

lating the criteria upon which selection is

based. This is what is now known as 'hard

systems thinking' , a systematic approach to

achieving defined objectives.

It was in the 1970s and 1980s that a more

systemic use of systems ideas was developed in

a programme of action research aimed at

finding better ways of tackling the kind of

ill-structured problem situations in the real

world in which objectives are multiple, ambig-

uous and conflicting (Checkland 1981). This

produced what is now known as 'soft systems

methodology' ( ~ S M ) , a much-used comple-

mentary approach to that of systems engineer-

ing/systems analysis. Many practitioners

around the world have contributed to this

development of so-called 'soft' systems think-

mg.

SSM is a learning system, a system of

inquiry. It makes use of models of purposeful

human activity, each based on a particular,

declared, world view (since purposeful activity

seen as 'freedom fighting' by one observer may

be interpreted as 'terrorism' by another) .

These models are used as devices to explore

problematical situations. Comparing models

with the perceived real world structures a

debate about change, a debate which tries to

find accommodations between conflicting in-

terests which enable 'action to improve' to be

taken.

The difference between 'hard' and 'soft'

systems thinking lies in how systems thinking

is used. In the ' hard' mode the world is

assumed to contain systems; and they can be

' engineered' to work effectively. In the ' soft'

mode the world is taken to be problematical,

but it is assumed that the process of inquiry

into it can be organized as a system. It is this

shift of systemicity from the world to the

process of inquiry into the world which marks

the hard/soft distinction. In practical terms

the 'hard' approaches are appropriate where

objectives or needs are well-defined, the 'soft'

approaches in ' messier' situations.

More recently, Ulrich's (1983) development

of the work of Churchman (1971) has drawn

at on to the need, where practical social

phwning is concerned, to open up the propo-

sals of experts to examination by lay persons

who will be affected by what the planners

design. Ulrich's ' critical heuristics' stresses

that every definition of a problem and every

choice of a system to design and implement

will contain normative assumptions which

need to be teased out and subjected to critical

scrutiny. The aim is to enable practical uses of

systems thinking to be emancipatory both for

those who are involved and those who are

affected.

4 Varieties of systems thinking

It is not possible in a short article to cover all

the r::1.ny varieties of systems thinking. But it

IS p:' .ible to define a setof categories which at

Systems

least enables us to make sense of any version of

systems thinking which we may come across,

whether in the literature of the past, in present

practice or in potential future developments.

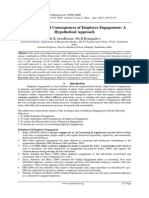

The categories which make this possible are

shown in Figure 1.

It is important to see Figure 1 not as a map

of systems work but as a way of making sense

of the wide range of examples of such work.

Any actual use of systems ideas may draw on

several categories; but it will be describable-

using these categories. It will be useful to give

some examples of this.

Thus, area 1 in Figure 1 would include the

development of cybernetics, which its pioneer

Wiener ( 1948) called ' the entire field of control

and communication theory whether in the

machine or in the animal' (see WIENER, N.) .

Many people have used cybernetics within

area 2.1 and users of organizational cyber-

netics (Beer 1979) could do so in several ways,

consciously using the cybernetic model either

as an account of the realworld(area2.11) or as

a device to explore complex reality (area 2. 12)

- or; indeed, both.

Similarly, a study in an organization, using

SSM, part of area 2.12, might well reach the

conclusion that , say, a system to control

product quality to meet certain criteria ought

to be set up. Designing and implementing such

a system might then be done using the

approach of hard systems engineering, area

2. 11. As a final example, a RAND-style study

Work in the systems movement

~

1 Development of systems

thinking as such

2 Application of systems

thinking

2.1 Applications 2.2 Applications in

other fields in management

I

2.11 Use of hard 2.12 Use of soft 2.13 Aid to

systems

thinking

systems

thinking

decision

makinQ.

Figure 1 Categories which can make sense of the wide range of work within the systems movement

4745

Systems

(Optner 1973) using, say, cost-benefit analysis

to help managers facing a major policy deci-

sion (area 2.13) would be enriched by placing

the decision in question in a systems context

such as could be provided by soft systems

thinking.

The systems literature contains more than

enough accounts of systems approaches in the

management field. This article concentrates

on methodologies which have been: used ex-

tensively, have generated secondary literature

and have been shown to be transferable from

the pioneers to other groups of users. Several

have been described above: systems engineer-

ing, RAND systems analysis, SSM, critical

heuristics. This section will end with brief

indications of six other approaches which have

had a significant impact on management

practice.

(1) Studying inventory problems in manufac-

turing companies, Forrester (1961) developed

a simple way of modelling material storage

and flows governed by policy criteria. This

'industrial dynamics', as it was first called, was

later generalized to 'system dynamics' (SD)

and extended well outside the field of inven-

tory problems. SD modellingwas the basis of

. the world models which were in vogue in the

1970s (Meadows eta!. 1972). The SD com-

munity flourishes but has remained rather

isolated within the systems community, with

its own journal and conferences.

(2) . When the technology of the UK coal-

mining industry was changed radically in the

1950s, the change affected not only the tech-

p i ~ ! aspects of winning coal from a harsh

envi\onment but the whole social structure of

the industry (Trist eta/. 1963). Studying this,

the researchers from the Tavistock Institute

proposed a 'sociotechnical system' as an ex-

planatory device. Based upon viewing an

organization as an open system in interaction

with its environment, the sociotechnical

model makes technology, social system and

environment interdependent: you cannot

change one without changing all. This has

been a very influential concept, a mainstream

of thinking in organization theory of a func-

tionalist kind, concerned to explain how the

parts of an. organization contribute to a

coherent whole (see TRIST, E.L.).

4746

(3) After forty years of experience in the

world of affairs, Sir Geoffrey Vickers sought

in retirement to make sense of what he had

experienced. He found systems thinking help-

ful and developed his theory of 'appreciative

systems' as an account of the social process

(1965). In an appreciative system we notice

certain features of our world as significant, as

a result of our previous experience. We dis-

criminate and judge such features using stan-

dards of good/bad, interesting/uninteresting

and so on, and we take action in tenns of

managing networks of relationships which are

important to us. However, the source of the

standards is the previous history of the system

itself, so that our social world continuously

reconstructs itself out of its own past. Interest

in Vickers' work is spreading as its relevance to

modern management is perceived.

(4) In his 'interactive planning' Ackoff (1974)

argues for a systems approach to societal

problems. His influential work is based on

the idea that the real world is characterized not

by 'problems' but by 'systems of problems' or

'messes' and requires a highly participative

approach based on planning. He describes five

interacting phases, planning for ends, means

to those ends, resourcing achievement of ends,

organizational arrangements necessary to

achieve them and implementation and control

- the latter being important since all outputs

call for revision in the light of experience. The

central idea is to start from an imagined ideal

future for the system being planned for, one

which ignores all constraints. The effort is then

directed to getting as close to that ideal .as

possible.

(5) Though Wiener's original cybernetics

(1948) focused on the nature of control sys-

tems, whether in machines or animals, the

best-known work on organizational or man-

agement cybernetics, that of Beer (1979),

extends that concept. Beer develops a sophis-

ticated model, the viable systems model

(VSM), having five interacting subsystems

which, he argues, are necessary and sufficient

for the survival of an autonomous whole in its

environment. In tenns of an organization,

system one is a set of operational elements

which make up an organizational entity;

system two is an anti-oscillatory mechanism;

system three the management unit responsible

for system one, internally, now; system four is

responsible for the external and future; system

five for monitoring the three-four interaction.

The sophistication of the model lies in its

never-ending, recursive nature: systems two,

three, four and five constitute the system one

of another level. Many managers have made

use of the VSM in understanding and ordering

their organizations.

(6) Finally there is currently interest in the

implications of a systems model created by

Maturana and Varela (1980) to make sense of

living systems. Their autopoietic (self-produ-

cing) model has elements whose action creates

the system itself as a stable pattern of relations.

They have reservations about applying th(!

model to a social whole, such as an organiza-

tion, but it is proving to be at least a rich

metaphor for thinkini about organizational

phenomena.

5 The future of systems thinking

In everyday language we casually speak of'the

legal system', 'the education system' , 'health

care systems' as if these were systems unequi-

vocally existing in the world. In fact, these

features of our world reveal very imperfect

versions of systemic properties as these have

been defined in the field of systems. Everyday

language uses ' system' to mean simply some

complex whole. Systems thinking has supplied

a variety of accounts of that complexity and

has created an epistemology and a language

which can be used to discuss many different

phenomena- natural or designed, concrete or

abstract. 'System', properly used, is the name

of a concept which may or may not map the

world as we experience it.

In the past, most work in the systems

movement followed everyday language in

assuming the world to consist of interacting

systems. More recently emphasis has been on

using the systems language to try to make

sense of the world as we experience it, in

particular modelling processes rather than

entities.

Helped by the ease and density of instant

communication, old boundaries dissolve and

former taken-as-given hierarchies become ir-

. Systems

relevant. Managers increasingly need to 'read'

their world as if it were a text which can be

interpreted in multiple ways. The crucial

management skill remains that of making

sense of the complexity faced. Process model-

ling based on systems thinking offers a power-

ful tool for managers in the future.

Further reading

PETER CHECKLAND

LANCASTER UNIVERSITY

(References cited in the text marked *)

* Ackoff, R.L. (1974) Redesigning the Future, New

York: Wiley. (An accessible account of ' inter-

active planning' by its major pioneer.)

*Beer, S. (1979) The Heart of Enterprise, Chiche-

ster: Wiley. (The Viable System Model dis-

cussed in detail by its creator.)

Berlinski, D. (1976) On Systems Analysis, Cam-

bridge, MA: MIT Press. (A polemical attack

on some of the pretensions of GST and

Systems Analysis.)

* BertalanfTy, L. von (1968) General System The-

ory, New York: Braziller. (Collected articles by

a founding father of GST: the authentic fla-

vour is conveyed.)

Boulding, K. (1956) ' General systems theory-

the skeleton of science' , Management Science 2

(3): 197-208. (The most famous systems pa-

per? An intuitive classification of system types

according to their complexity.)

*Checkland, P. (1981) Systems Thinking, Systems

Practice, Chichester: Wiley. (Systems thinking

1

a:Sarejection of scientific reductionism; and an

account of SSM's development.)

Checkland, P. and Casar, A. (1986) ' Vickers'

concept of an appreciative system: a systemic

account', Journal of Applied Systems Analysis

13: 3-17. (Vickers' account of the social pro-

cess presented in the form of a systemic

model.)

Checkland, P. and Scholes, J. (1990) Soft Systems

Methodology in Action, Chichester: Wiley. (An

account of mature SSM and its use in industry

and the public sector.)

Churchman, C. W (1968) The Systems Approach,

New York: Dell Publishing. (Enjoyable philo-

sophical ruminations on what it means to use

'a systems approach'.)

*Churchman, C.W (1971) The Design of Inquiring

Systems, New York: Basic Books. (Deep-ex-

amination of systems design through the ideas

of Leibniz, Locke, Kant, Hegel, Singer.)

4747

Systems

Espejo, R. and Harnden, R. (eds) (1989) The

Viable. System Model, Chichester: Wiley. (Ar-

ticles discussing the interpretation and use of

Beer's VSM.)

Flood, R. and Jackson, M.R. (1991) Critical

Systems Thinking: Directed Readings, Chiche-

ster: Wiley. (Articles concerning the need to

examine the normative implications of sys-

tems-based problem-solving methodologies.)

* Forrester,J.W (1961) Industrial Dynamics, Cam-

bridge, MA: Wright-Allen Press. (The book

that established the field which became known

as 'system dynamics'.)

*Hall, A.D. (1962) A Methodology of Systems

Engineering, Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

(The classic account of 'hard' systems engi-

neering, generalized from Bell Telephone's

experience.)

Katz, D. and Kahn, R.L. (1966) The Social

Psychology of Organizations, New York:

Wiley. (Organizations treated as open systems

with functional parts, interacting with an

external environment.) .

* Maturana, H. and Varela, F. (1980) Autopoiesis

and Cognition: The Realization of the Living,

Dortrecht: Reidel. (A seminal account of a

self-producing system as an epistemological

device for understanding living systems.)

*Meadows, D.H., Meadows, D.L., Randers, R.

and Behrens, W. (1972) The Limits to Growth,

New York: Universe Books. (System dynamics

applied on a world scale: this was controversial

but modish for a time.)

Miller, J.G. (1978) Living Systems, New York:

McGraw-Hill. (A mammoth work. describing

living systems as containing nineteen neces-

sary sub-systems; contrast this with the autop-

oietic model.)

Mingers, J. (1995) Self-Producing Systems, New

York: Plenum Press. (An excellent discussion

of autopoiesis and its implications in many

fields.)

Miser, H.J. and Quade, E.S. (eds) (1985; 1988)

Handbook of Systems Analysis, New York:

North Holland. (A two-volume compendium

4748

on all aspects of (mainly 'hard') systems

analysis in real-world problem solving.)

Open Systems Group (eds) (1984) The Vickers

Papers, London: Harper & Row. (A valuable

collection of Vickers's writing, tackling issues

at world, societal, organizational and indivi- .

duallevels.)

* Optner, S.L. (ed.) (1973) Systems Analysis, Har-

mondsworth: Penguin. (Articles on RAND- .

style systems analysis, including Charles

Hitch's 1955 account of RAND thinking.)

Rosenhead, J. (ed.) (1989) Rational Analysis for a

Problematic World: Problem Structuring

Methods for Complexity, Uncertainty and Con-

flict, Chichester: Wiley. (The book now seen as

establishing 'soft OR', though that phrase is

not used.)

Sage, A.P. (1992) Systems Engineering, New

York: Wiley. (Usefully updates Hall's 1962

book, covering systems methodology and sys- .

terns design and management.)

* Trist, E.L., Riggin, G.W, Murray, H. and Pol-

lock, A.B. (1963) Organizational Choice, Lon-

don: Tavistock Publications. (The emergence

of the 'socio-technical system' concept.)

*Ulrich, W (1983) Critical Heuristics of Social

Planning, Bern: Haupt. (A conceptual frame-

work aiming to reveal and reflect upon the

normative implications of inter alia plans and

designs.)

*Vickers, G. (1965) The Art of Judgement, Lon-

don: Chapman and Hall. (Vickers' original

account of the social process as 'an apprecia-

tive system' , republished in 1984 by Harper &

Row.)

*Wiener, N. ( 1948) Cybernetics, Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press. (The classic account of commu-

nication and control in machines and living

things.)

(

See also: ORGANIZATION BEHAVIOUR;

ORGANIZATION BEHAVIOUR, HISTORY OF;

SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND DESIGN; TRIST, E.L.;

WIENER, N.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Pito Perez 5 o 6Document3 paginiPito Perez 5 o 6ScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robbie Williams Its Only Us Guitar TabDocument2 paginiRobbie Williams Its Only Us Guitar TabScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gt100 4 Cable Method To Amp StackDocument2 paginiGt100 4 Cable Method To Amp StackScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dolemite: Scott HendersonDocument17 paginiDolemite: Scott HendersonScrberto100% (1)

- Pimping and Repairing An Epiphone Custom Ebony by Arnold Dikstaal and Thomas SchmidtDocument42 paginiPimping and Repairing An Epiphone Custom Ebony by Arnold Dikstaal and Thomas SchmidtScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Fender TBX Tone Control Mod, Part 2Document2 paginiThe Fender TBX Tone Control Mod, Part 2ScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beatles Octopus's Garden SongDocument3 paginiBeatles Octopus's Garden SongScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Foo Fighters ExahustedDocument2 paginiFoo Fighters ExahustedScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Robbie Williams Its Only Us Guitar TabDocument2 paginiRobbie Williams Its Only Us Guitar TabScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Please Read Through Instructions Completely Before Beginning Your Installation.Document4 paginiPlease Read Through Instructions Completely Before Beginning Your Installation.ScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guitar Wiring FAQsDocument3 paginiGuitar Wiring FAQsScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guitar Wiring FAQsDocument3 paginiGuitar Wiring FAQsScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Beatles Octopus's Garden SongDocument3 paginiBeatles Octopus's Garden SongScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Guitars Design Production and RepairDocument161 paginiGuitars Design Production and RepairPelon1100% (2)

- Jumbo Monotransistor GuitartabDocument2 paginiJumbo Monotransistor GuitartabScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- 7040Document89 pagini7040ScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Darwin 200 BookletDocument23 paginiDarwin 200 BookletSuhana NanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Electric Guitar Service ManualDocument44 paginiElectric Guitar Service Manualpicaaman100% (1)

- PHD ThesisDocument31 paginiPHD ThesisAkash AkuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Future Generation Passenger CompartmentDocument13 paginiFuture Generation Passenger CompartmentScrbertoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe la EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De la EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Evaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe la EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe la EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe la EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe la EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe la EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe la EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe la EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe la EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe la EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe la EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe la EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe la EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe la EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe la EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyEvaluare: 3.5 din 5 stele3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe la EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De la EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Evaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe la EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesEvaluare: 4 din 5 stele4/5 (821)

- Foundations of CurriculumDocument10 paginiFoundations of CurriculumIvaline Febriansari100% (1)

- Filosofi Dan Paradigma KeperawatanDocument20 paginiFilosofi Dan Paradigma KeperawatanFAUZIAH HAMID WADAÎncă nu există evaluări

- Instructional Planning DLP FormatDocument5 paginiInstructional Planning DLP FormatAlvin Cuandot100% (1)

- Change Management OD MBA III 378001045Document4 paginiChange Management OD MBA III 378001045Patricia MonteferranteÎncă nu există evaluări

- A Model of The Communication ProcessDocument38 paginiA Model of The Communication ProcessMOHAMMED ALI CHOWDHURY100% (3)

- Micropolitics in Schools: Teacher Leaders' Use of Political Skill and Influence TacticsDocument11 paginiMicropolitics in Schools: Teacher Leaders' Use of Political Skill and Influence TacticsArgirios DourvasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching Materials and Teaching Aids - IIDocument15 paginiTeaching Materials and Teaching Aids - IIrohityadavalldÎncă nu există evaluări

- Application of Attachment Theory To The Study of Sexual AbuseDocument11 paginiApplication of Attachment Theory To The Study of Sexual AbuseBea100% (3)

- Engineering and The Mind's EyeDocument14 paginiEngineering and The Mind's EyeDushyantha Jayawardena100% (2)

- Brain Compatiple Learning FinalDocument19 paginiBrain Compatiple Learning Finalapi-265279383Încă nu există evaluări

- Listening Is ImportanceDocument12 paginiListening Is ImportanceZhauroraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Benefits of Drum Circles for Team TrainingDocument4 paginiBenefits of Drum Circles for Team TrainingMishu UhsimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic Human Resource DevelopmentDocument231 paginiStrategic Human Resource DevelopmentIram Imran100% (2)

- Ethics of Nursing Shift ReportDocument5 paginiEthics of Nursing Shift ReportkelllyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Meta Masters PDFDocument272 paginiMeta Masters PDFGarb Poub100% (1)

- Traffic Psychology Today PDFDocument373 paginiTraffic Psychology Today PDFSergio100% (2)

- Attachement 261Document22 paginiAttachement 261Sheron LeeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Intro Abnormal PsychologyDocument30 paginiIntro Abnormal Psychology1989920198950% (2)

- Emergent Patterns in Dance Improvisation and ChoreographyDocument9 paginiEmergent Patterns in Dance Improvisation and ChoreographyFecioru TatianaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theories of Motor LearningDocument58 paginiTheories of Motor LearningIndira Naidu Boddapati60% (5)

- Comparison of Servant Leadership and StewardshipDocument10 paginiComparison of Servant Leadership and StewardshipAndy MarsigliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Getting 360 Degree Feedback RightDocument13 paginiGetting 360 Degree Feedback RightLawi Anupam100% (2)

- IntroductionDocument39 paginiIntroductionMohd FazliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Employee Engagement - Hypothetical AnalyseDocument6 paginiEmployee Engagement - Hypothetical Analyseroy royÎncă nu există evaluări

- Interview On Peer Relationships: Tahir KholaDocument4 paginiInterview On Peer Relationships: Tahir KholaÃrêêbã ÅsĦfåqÎncă nu există evaluări

- PSYC1002 Research ReportDocument7 paginiPSYC1002 Research ReportJoyce SunÎncă nu există evaluări

- HandoutsLaneCommunityCollege PDFDocument32 paginiHandoutsLaneCommunityCollege PDFImafighter4HimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Self Empowerment Workshop OutlineDocument2 paginiSelf Empowerment Workshop Outlinepedo1972Încă nu există evaluări

- Boost your creativity with these exercisesDocument4 paginiBoost your creativity with these exercisesKoni DoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Decision Making Decision Making: Dr. Manahan SiallaganDocument23 paginiDecision Making Decision Making: Dr. Manahan Siallaganheda kaleniaÎncă nu există evaluări