Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Glenda Gloria Media in The Philippines

Încărcat de

Happy Jayson MondragonDescriere originală:

Titlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Glenda Gloria Media in The Philippines

Încărcat de

Happy Jayson MondragonDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Media and Democracy in the Philippines

The Philippines has been on the news for five long months now due to a noisy, media savvy group of kidnappers that had abducted foreign hostages in April. During that period, we witnessed the spokesperson of the Abu Sayyafjoin the league of world leaders and experts in gaining precious airtime on CNN live. Local reporters as well were free to visit the kidnappers' lair by foot and air their interviews with them day after day. This would have been unthinkable in Malaysia or Singapore or even maybe Indonesia. However, the Philippine military later imposed a news blackout on its operations on Jolo Island where the kidnappers had encamped. Journalists who had been allowed to deliver soundbites on kidnappers were now banned from delivering the civilians'stories about the devastation of their province by the military. How exactly should media act in such a tough situation? What judgments should it make that would serve public interest and adhere to the fundamentals of a functioning democracy? This paper seeks to answer these questions.

GLENDA M GLORIA

ecause of its critical role in the dying years of the Marcos dictatorship that eventually culminated in a mass uprising in 1986, the Philippine media takes pride in its role in bringing democracy back to the country. Because of its long tradition as the freest press in Southeast Asia, the Philippine media is often expected to take the lead in debating, shaping and crafting media's role in a democracy. But we sometimes could not meet such expectations for a number of reasons. The Philippines is a nation in perennial transition trapped in many contradictions. It is a nation that made world history when it oustedthrough a relatively peaceful mass uprisingthe late dictator Ferdinand Marcos in 1986. But it is also a country that continues to be wracked by the same insurgencies and rebellions that many thought it had already succeeded in defeating just a few years ago. As its population balloons to about 70 million diverse people, the Philippines enters the 21 st century with unsettled problems that are rooted in the complex historical circumstances that had shaped its state-formation. There are 80 languages spoken in the Philippines, excluding English. And its geography of 7,100 islands makes its regions fragmented and divided by seas and mountain ranges. Most residents of Metro Manila, for example, are so far removed from rural life. The young educated elite probably know more about the United States than about the Philippines' troubled region, Mindanao. In Southeast Asia, the Philippines stands out as what the West would generally describe as the 'freest democracy' in

Glenda M Gloria is Editor, Philippines Center for Investigative Journalism, Manila.

the region. It is a kind of democracy inherited from and even patterned after America: a presidential form of government, a bicameral congress, a noisy press. The United States seized the Philippines from Spain in 1898, after the latter's 350-year occupancy of the country. Under Spain, Filipinos staged Asia's first war of national liberation. Under the United States, Filipinos were perennially torn between collaborating with this colonial power or fighting it. (Table 1). Yet the most compelling political experience that Filipinos had to undergo since gaining independence in 1946 is the dictatorial rule of Ferdinand Marcos, who had served longest as president, from 1965 to 1986. Faced with twin problems posed by communist insurgency and Moro separatist rebellion, Marcos declared martial law in 1972. Hejailedhis opponents, shut down critical newspapers and broadcast stations, and launched massive attacks on villages known to be rebel enclaves. But the EDS A people power revolt came in 1986, and with it a newfound hope for Asia's bastion of democracy. Marcos was forced to flee to Hawaii where he died four years later. A strongman had bowed down to the sheer strength of a mass of people demanding his ouster. Still, the post-Marcos era rebuilding process has not been easy. While the previous Aquino government laid down the foundation for a transition from authoritarianism to democracy, it had to put down six coup attempts against it by the rebel military officers that had played a critical role in ousting Marcos. The first free local elections in the postMarcos era were held in 1987. By 1992, then former President Corazon Aquino supervised a smooth leadership turnover that witnessed the first free presidential race in two decades.

191

MEDIA ASIA, VOL 27 NO 4, 2000

Table 1 The Philippine Media A Numbers Game

Newspapers 11 English and 2 Filipino broadsheets circulated nationwide. Biggest circulation is Inquirer (about 240,000) e 18 Manila-based tabloids and five Chinese-language daily newspapers 408 Community Newspapers (daily, weekly, bimonthly, etc). About 22 are published daily (circulation a low of 500 and high of 45,000). Radio 539 stations nationwide (273 of them AM). Of these, there are 11 religious stations and 5 educational stations.

TV 6 63 principal TV stations (6 of which are Manila-based & 2 run by government) 150 smaller TV stations in provinces. 24 UHF stations. Cable TV: 300 cable operators nationwide

Traumatic past

This is partly due to institutional factors. The trauma of the Marcos years has made some media entities naturally adversarial to government. The gain from this kind of approach is it puts the power elite on their toes as they perform their public functions. The downside to this is a self-conscious effort on Philippine media's part to go for the 'big' stories, fight the 'big' powers at the expense of many other important stories on policy and other 'little people.' The 1986 'people power' revolution that ended 14 years of state control of the press brought about vast changes in the entire industry. Overnight, a dozen newspapers were published, many other radio and TV stations opened up, and the formerly Marcos-controlled news agencies either closed down or were seized by the new government. Newspapers Today there are 11 English and two Filipino (the main Philippine language) broadsheets circulated nationwide, compared to only three broadsheets during the Marcos era. At present, there are also 17 Manila-based tabloids and five Chinese-language daily newspapers serving the huge Chinese community in the Philippines. (Table 2) The big number of newspapers in circulation does not mean a wide reach for them. Estimates made in 1990 showed that only a little over three per cent of the population buy newspapers. Yet, according to a 1994 survey of the Asia Research Organization (ARO), 63 per cent of the population read newspapers, many of them only sharing copies of those with the means to buy (Coronel, 1998). Readers are concentrated in the urban areas, mostly Metro Manila. The tabloids also enjoy tremendous edge over the newspapers. In 1990, although tabloids were about a third of the total number of dailies, they accounted for half the total circulation figures. The Philippine Daily Inquirer, for instance, has a claimed circulation of 240,000. The former leader of the pack, the Manila Bulletin, is down to less than 200,000, according to various industry sources. The informal consensus in the newspaper industry, however, is that the total circulation of the Manila-based broadsheets and tabloids is about 1.5 million. The Philippines has a population of 70 million. Thus, it can be said that the increasing number of newspapers nationwide despite stagnant readership is in itself a phenomenon. Radio and TV The performance of radio and TV stations is a different story altogether. There are 539 radio stations nationwide. The bulk of the radio stations are commercial, although the government has retained ownership of 32 AM and one FM station. There are 11 religious stations and only five educational stations, most of them on FM. AM radio is still the dominant format nationwide, except in Metro Manila where FM radio controls 68 per cent of the audience. There are six Manila-based TV stations that have a national reach. Two of these are ran by government

(as of 1998/Sources: PCU, KBP)

The current president, Joseph Estrada, is the third president in the post-Marcos era of democratic rebuilding. Fresh into his term as president in 1998, Estrada did not get the traditional honeymoon with the press. Newspapers immediately went to town with critical stories about him. As he entered his second year in office, he filed a libel suit against one newspaper that forced the latter's temporary closure. Almost simultaneously, his friends from the business community pulled out their advertisements from the country's largest newspaper, Philippine Daily Inquirer, causing revenue losses estimated at P10 million. But that is going ahead of the story.

Media profile

Many would say that the Philippine media, while probably the freest in Asia, has abused its freedom. It is, critics say, noisy but vulnerable, powerful but irresponsible. Without doubt, however, Philippine media enjoys an advantage not present among its counterparts in the Asean region. It not only operates in a democratic environment; it appreciates the democratic freedom afforded them. It is this that allows Philippine media to recognize the link between empowerment and information. The rowdy and mighty media agencies play a big influence over Philippine society. They expose the abuses or incompetence (or both) of politicians and bureaucrats. As such, media have played a role in the democratization processby holding public officials and institutions accountable to their oaths of office. But the excesses of media are well known. As such, media has sometimes been blamed for the absence of sober and intelligent debate that is also crucial in a democracy. Indeed, like most Philippine institutions, the Philippine media is weak, hobbled by the same systemic and contextual problems that threaten democracy today.

192

MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY IN THE PHILIPPINES

Table 2 The Philippine Media Historical Context

1890-1900 1901-1946 (Spanish period) Rise of the revolutionary press (American period) A Filipino bought The Manila Times from an Englishman. Began a chain of newspapers Radio introduced in RP by an American (Post-Independence) US-inspired press Declaration of Martial Law. Newspapers/ broadcast stations shut down Rise of Alternative Press ("We Forum') Formal 'lifting' of Martial Law New wave of arrests of journalists Assassination of Ninoy Aquino; rebirth of alternative press Boycott campaign vs 'crony' press Birth of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, etc. EDSA revolt; Marcos is ousted Cory opens doors for more media agencies Coup-prone years of Cory government Presidential race; Ramos elected president Inquirer catches Ramos' ire Estrada elected president Critical press catches Estrada' ire

1922 1946-1972 1972 1977 1980 1982 1983 1983-1984 1985 1986 1987 1987-1989 1992 1992 1998 1998-1999

Source: Maslog, Crispin, The Metro Manila Press, 1994; Own inputs

RPN-9 and IBC-13, pending their eventual privatization. In addition, over 150 smaller TV stations operate in the provinces. There are 24 UHF channels. Cable television has grown in the 1990s, with some 300 cable operators currently operating nationwide. Records showed that in the 1980s, only a third of all Filipino households owned TV sets. In the last decade, however, broadcasting executives estimated that Filipinos bought some 500,000 new TV sets every year. In 1992,82 per cent of families owned radios, while 54 per cent owned a TV set. By 1997, the ARO found that nationwide, 84 per cent watched TV compared to 81 per cent who preferred radio. Indeed, in the last decade, the real growth in terms of audience reach has been in radio and television. The ABS-CBN TV station is the acknowledged leader of the TVpack. In 1995, ABS-CBN contributed55 percent of the PI.6 billion net income of Benpres, the Lopez conglomerate's parent company. ABS has cornered 45 per cent of the billions in advertising money poured into TV stations.

in the 19th century had been preceded by the growth of a revolutionary press. After the US' takeover of the Philippines from Spain, the Philippine press drew heavy influence from US style of reportage and private ownership. The repressive martial law years from 1972 to 1981, however, killed critical media and out of it grew a crony press. A controlled press for 14 years concealed problems of corruption in government and mismanagement of the bureaucracy. When freedom was restored after the 1986 ouster of Marcos, the nation was witness to a freewheeling, market-oriented press that had come to take its watchdog role seriously. The history of the Philippine media reflects the contradictions of how the Philippines was shaped as a nation. The American legacy is a freewheeling, enterprisebased press system. The situation turned for the worse in 1972, when then President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. Nonetheless, a fearless bunch of young and old journalists did not take this repressive rule lightly. In 1977, veteran journalist Jose Burgos Jr put up a fiercely independence weekly magazine for the youth called We Forum. Five years later, the magazine was padlocked and Burgos was put to jail. Military censors continued to padlock critical press agencies. They reported directly to then defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and Public Information chief Francisco Tatad, who both headed the so-called Committee on Mass Media (Maslog, 1994). The lifting of martial law in 1980a mere faceliftdid not help improve the situation. In 1982, in fact, the military staged a second wave of mass arrests of journalists. After his release from jail in 1983, journalist Burgos decided to publish a daily newspaper called Malaya. That year, Ninoy Aquino was assassinated, and the media was never the same again. Press freedom in this case is not only a product of street struggles. It is stipulated in Philippine laws. The Philippine Constitution of 1935, 1973 and 1986 guaranteed that "no law shall be passed abridging freedom of speech and of the press."

Development of democracy

The 1986 EDSA people power revolt strengthened the bias for accountability and respect for human rights. Out of it emerged a vibrant civil society with a strong developmental orientation (Magadia, 2000). The post-Marcos era unleashed the Filipinos' energy and stamina for democratic reform. The 1987 Constitution crafted by the Aquino government, for instance, spells out clearly the role of NGOs in nation building. With press freedom restored, the media went beyond its traditional sources of news and gave NGOs and mass movements a bigger voice in and access to the news process. The NGOs and protest movements had found new and reliable partners in media. Media, for instance, took part in the healing process for victims of military abuses under the Marcos regime. Newspapers and TV stations uncovered and exposed various

193

State of affairs

The media had come to this not by accident. For Philippine media today is a product of context and history. Four milestones in Philippine history have shaped the structure and values of the media. The revolt against Spain

MEDIA ASIA, VOL 27 NO 4, 2000

stories on past killings, massacres and kidnappings of political activists by abusive soldiers. In this case, media highlighted human rights stories as well as advocacy issues on land reform and workers' rights by sectors. In 1990, the issue of US bases took center stage. Media played up the highly charged debate on whether or not to allow the continued presence of American troops on two bases in the Philippines. In 1991, the Senate, despite pressures from various sectors, voted against the US bases.

Challenges

What causes these obstacles to a free but responsible and proactive press? There are key reasons for these: Ownership The media are owned by big business (The only exception to this is the Businessworld, a respected business newspaper that is 70per cent owned by its staff). Business people buy newspapers even if they seem to be a losing venture. The explanation to this is simple: business people buy newspapers because their aim is not profit but influence and power. Some owners have been using their newspapers either to put down their rivals or even merely to seek political legitimacy by cozying up to the powers that be. To be sure, the nature of media ownership over the last two decades has been influenced by the fortunes of big business, too. Immediately after 1945, Spanish-mestizo business people like the Roceses owned the presses. The 1980s (after the dictatorship) witnessed the emergence of a new media clique in business: the Chinese-Filipino community. Thus, Emilio Yap purchased the Bulletin', the late Betty Go-Belmonte produced the Philippine Star, the Yuchengco family came up with the Manila Standard; and the Gokongweis bought the Manila Times. The Yuchengcos had sold out to a Filipino owner, however, and so have the Gokongweis. It is a known fact that except for the top three newspapers (Inquirer, Bulletin and Star), nearly all the rest are being subsidized by their owners' other businesses. It is the same business interests that make them vulnerable to government pressure, as what the Manila Times case has proven. (The Gokongweis, who were pressured to sell their newspaper in July 1999 to a friend of President Estrada, had been publishing the Times for 10 years and had kept a comfortable distance from editorial matters. However, Estrada filed a libel suit against the newspaper in March 1999, over a story that called him an 'unwitting ninong (godfather)' to abad government contract. The Gokongweis eventually sold the newspaper to presidential friend Mark Jimenez. It is widely believed that prior to the sale, the Gokongweis' had encountered problems in their other bigger businesses that were subject to government regulation. The Gokongweis are also into food, airline, telecommunications, banking and finance, real estate, hotel and recreation, power generation, and mining and oil exploration.) Families with interlocking business interests own two of the country's biggest newspapers: 1. Philippine Daily Inquirerthe Prieto/Rufino families are into food, real estate, paper production, and other services. 2. Manila BulletinEmilio Yap's interests include the Bataan Shipyard and Engineering Corp.; Manila Prince Hotel; US Automative Co. Inc.; and Manila International Port Terminal, among others. The third largest newspaper, the Philippine Star, is run by

Post-transition

In short, the Philippine media took its task seriously in the post-Marcos transition regime of Mrs Aquino. But sadly, Filipino journalists' defence of democracy has not gone beyond protesting bad government and denouncing perceived threats to press freedom. Thus at every turn, when it smelled threat to press freedom, media was the first to raise howl. In 1995, the Ramos government flirted with thought of amending the Constitution to extend the President's term. Major media players protested this no end. In 1995, The Manila Times exposed a draft constitution of the National Security Council, and the campaign to tamper with the Constitution began to die. But a nation in political transition had to confront other challenges. These include the demands of a changing and growing economy, the problems of a mismanaged bureaucracy, the long-festering feudal character of its politics, badly needed electoral reforms, poverty, etc. The democratic institutionsjudiciary, legislative, executive were hobbled by structural problems brought about by long years of neglect. Media, to fulfill a role in a democracy, was expected to go beyond the expose-and-oppose type of reportage that it had been used to under Marcos and Aquino. Critics have accused media of focusing too much on the horse race in election periods. In key policy issues, media would often report more on the personalities entangled in the policy mess and seldom get to the bottom of the issues being debated. This is where the media have largely failed to meet the demands of a growing democracy. But it could be argued that media is a mere reflection of a democratic society that has not fully matured and which continues to be confronted with many challenges to this day. Manila-based journalists remained so centered on the goings-on in the capital, far removed as they are with the real stories in the countryside. The Local Government Code, which was implemented in 1992, gives local government units better access to financial resources. This is in the form of automatic appropriation of 40 per cent of internal revenue collections to LGUs, greater taxing powers for them, as well as authority to incur debt and to solicit official development assistance. Decentralization is generating profound changes in local politics, but that has not been fully documented in general by Philippine media. Mindanao remains to be the source of war stories as far as many Manila-based media are concerned. The many success stories of development efforts in select areas in Mindanao are underreported or in most cases ignored.

194

MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY IN THE PHILIPPINES

the family of Feliciano Belmonte Jr., member of the House of Representatives and currently minority leader representing the Larkas-NUCD party. The top radio station is DZRH, owned by the Elizalde family. The business clout of this Spanish-mestizo family has diminished over the years. Meanwhile, ABS-CBN TV station was given back to its former owners, the Lopez family, who returned from exile in the United States after Marcos' ouster in 1986. The Lopezes' other business interests include telecommunications, power, water and infrastructure. They also own DZMM, the country' s second largest radio station. Government is also into media. It runs three TV stations, RPN-9, IBC-13 and PTV-4. Privatization, however, is being finalized for RPN-9 and IBC-13, because both had suffered huge losses over the last decade. Government also continues to own the Journal group of publications, which now runs two tabloids (one in English and the other in Filipino). The main publication of the government-run Journal group was the Times Journal, but this closed shop early this year due to heavy losses. Corruption This problem is pervasive in Philippine media and it is by no means a new phenomenon. Early written accounts about it go back to the 1950s, when journalists were bought off with cash by politicians and businessmen, according to a study conducted by Chay Florentino-Hofilena in 1998. She said a more systematic type of corruption emerged in the 1960s and early 1970s, when payoffs became an integral part of the regular news beats. Post-Marcos corruption of the Philippine press is more pervasive and even more systemic. The study said: 'It is also disturbingly creative and difficult to detect. Transactions have become more sophisticated, and in some cases, even institutionalized.' The organized way in which corruption takes place, the study explained is through a network of journalists reporting to other journalists or to professional public relations or PR people. This 'makes it more like the operation of a criminal syndicate, a mafia of corrupt practitioners,' the study concluded. In a survey conducted among 100 reporters by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism from September 1997 to March 1998, many of them acknowledged that reporters are offered money by their sources. Two of every five said they had received offers of money in the course of their coverage a number of times while close to one of every four replied rarely. The same survey showed that in some news beats, a number of reporters appeared to have taken a different role: that of brokers. Of the 71 reporters who said they had been offered money by their sources, nearly half identified another reporter as having made the overture. One third of the reporters who were offered money admitted to taking it. Of these, a third said they turned over the money to theneditors, although twice as many said they pocketed it. Skills and 'tabloidization' of news The freedom enjoyed by the media after the ouster of the

dictatorship has given journalists virtually blanket licence to hit anybody. Several exposes in the media had led to the resignation of public officials, the rescinding of bad government contracts, and the investigation of politicians and government executives as well. The environment has been conducive to investigative reporting and stories that raise public awareness on such issues as generic drugs, AIDS prevention, women's rights, etc. But in the race to get a big share of a limited market, Philippine media have also resorted to coming up with news that 'sell.' Stiff competition has distorted the conduct of journalism in this country, as well as the content of newspapers and the programming of radio and TV programmes. The result is the so-called tabloidization of news. TV stations have been forced to be more commercial, an abdication of their educational role. A bigger problem, however, is the level of skills of both reporters and editors. The media explosion in the postdictatorship era has flooded the industry with inexperienced journalists. Reporters were young and fresh from college, while the editors were mostly plucked from the Marcos era yet. The generation gap had a disastrous effect: on one hand, a bunch of young, idealistic but neophyte reporters who needed guidance; on the other hand, a bunch of aging editors many of whom had lost the stamina to direct, inspire and coach reporters. There is not enough on-the-j ob training and the turnover is fast, with young journalists eventually opting out of the profession in search of better-paying jobs. Starting pay for newspaper reporters ranges from P7,000 to PI0,000 a month. The same is true with photographers. Salaries in TV stations are higher, while contractualization is rampant in radio stations. Of the broadsheets, only the Inquirer, Bulletin, Malaya and Standard are unionized. The rest discourage their reporters from forming labor unions. Harassment/Government pressure There remains a high casualty rate among Filipino j ournalists based in the provisions. The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists puts the number of Filipino journalists killed since 1986 at 33. It is difficult to say how many of these were killed because of their work. But communitybased journalists face real danger in the provinces, where there is less tolerance for critical reporting. Philippine libel laws, which are patterned after that of the US, are less restrictive than those elsewhere. Libel in the Philippines is both a civil and a criminal offense. Officials and other parties who feel offended by critical reporting have been filing harassment suits against journalists. Fortunately, Philippine courts have tended to rule in favour of the freedom of journalists to report and to comment. The threat of advertisement withdrawals in retaliation for adverse reporting is common knowledge. Former Economic Planning Secretary Solita Monsod quit writing a column for the Star when a column she wrote critical of Lucion Tan, an Estrada crony, never saw print. In mid-1999, the Inquirer experienced a rush of ad pullouts by firms owned by business people close to

195

MEDIA ASIA, VOL 27 NO 4, 2000

President Estrada. These include Tan's firms, the PLDT owned by Manuel Pangilinan, all car companies owned by Chinese-Filipino business people, etc. Estrada also got the cooperation of movie producers who withdrew advertising from the paper. The Inquirer is the newspaper that has been most critical of the president. When its editors held a noholds-barred meeting with the President end of November this year, the ads began returning to the newspaper, one by one. What the Manila Times and Inquirer cases have shown is the sophisticated manner by which the present government deals with its 'media problems.' While state control a la Marcos days is not evident, the governmenthas nonetheless come up with more subtle and creative ways in muzzling the press. What has emerged is this: those who wish to control or silence the press do so through market mechanisms rather than the strong-arm tactic of the state. These are in the form of organized pressure from advertisers; more intense attempt to bribe journalists with perks and cash; and putting pressure on media owners who are vulnerable to government pressure because they own businesses that are subject to official regulation. Thus, while there exist open lines between government and media at this time, this is subject to constant test due to the latest incidents cited above.

Conclusion

'The media, even in the freest countries, are therefore squandering their potential to be an agent of positive change, to preserve a diversity of views, to give a voice to minorities, and to serve as feedback mechanism for policymaking in a democracy,' says journalist Kunda Dixit. That is the real challenge. The present situation calls on media to make a difficult balancing act between what a democracy like the Philippines needs and what it wants. Between this lies the role of media in fostering participatory governance. The Philippine media has served as forum for sectors and marginalized groups to air their grievances against government and present their views about specific government policies and decisions. But because of its weaknesses cited above, media's performance of that role leaves much to be desired. Beyond advocacy, after all, is the public's need for issues to be clarified, for events to be contextualized, and for complex issues to be given a broader perspective. The problem of the Philippines is not lack of information, but lack of proper information. It is not lack of opinion but a dearth of informed opinion.

Notes New landscape

The landscape is also changing for Philippine media. Patricia Arches, president of McCann Erickson Phils, cites studies showing declining newspaper readership. In many markets newspaper circulation is flat or declining while paper costs and other resources continue to drives advertising rates up. Today's youth, or those under 35, have stopped reading newspapers which they consider as their parents' medium. Says Arches: 'Newspapers worldwide are coming to the realization that the era of product-led internal decision-making in publishing is over, and marketing-led decision making is taking hold. Media owners are not steering the boat anymore, consumers are.' But one welcome development in this new global landscape is the Internet. With a very sensitive president currently at the helm, some critical stories that had been ignored by the major media have found its way on the Internet. The first story on Estrada's unexplained wealth by the PCIJ was circulated largely on the email. The website of the PCIJ also had a high record of visits in the aftermath of the stories. The new media is largely unexplored, but has potential for keeping alive the flow of information needed by a public hungry for more independent news from independent sources.

Almonte, Jose T. (2000), Philippine Politics in Transition, Politik, Ateneo Centre for Social Policy and Public Affairs. Asian Intelligence (1997), a quarterly report on Asian business and politics by the Political and Economic Risk Consultancy Ltd., Hong Kong. Coronel, Sheila, The State of the Philippine Press, A paper presented in various form in 1998. Press Freedom Endangered: Real, A speech before the Makati Business Club, 5 August 1999. De Jesus, Melinda (1996), Asian Values: Do They Exist? Media Asia, Asian Mass Communication Research and Information Centre. Philippines: The Problem with Freedom, News in Distress (The Southeast Asian Media in a Time of Crisis), Philippine Centre for Investigative Journalism and Dag Hammarskjold Foundation. Dixit, Kunda (1999), News in Distress (The Southeast Asian Media in Time of Crisis), Philippine Centre for Investigative Journalism and the Dag Hammarskjold Foundation. Hofilena, Rosario-Florentino, The Powers That Be, Politik, Ateneo Centre for Social Policy and Public Affairs. Magadia, Jose (2000), Introduction, Politik, Ateneo Centre for S ocial Policy and Public Affairs. Maslog, Crispin (1994), The Metro Manila Press, Philippine Press Institute, Manila. This paper was presented at the Amic Conference on 'Media and Democracy in Asia', held in Singapore from 27-29 September 2000.

196

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- The Effective Use of VolunteersDocument28 paginiThe Effective Use of VolunteersInactiveAccountÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Philippine Economy Development Policies and Challenges by Arsenio M. Balisacan Hal HillDocument493 paginiThe Philippine Economy Development Policies and Challenges by Arsenio M. Balisacan Hal HillHersie BundaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ethics Assignment 1Document3 paginiEthics Assignment 1Seslaine Marie S. PeletinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Comparative Public PolicyDocument20 paginiComparative Public PolicyWelly Putra JayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Week 7: Policy Models and Approaches 1: PA 241 Rbcruz, Up NcpagDocument24 paginiWeek 7: Policy Models and Approaches 1: PA 241 Rbcruz, Up NcpagMitzi SamsonÎncă nu există evaluări

- My Way of LeadingDocument4 paginiMy Way of LeadingLyn bacatan100% (1)

- Pa 214 Classmate HandoutsDocument4 paginiPa 214 Classmate Handoutsmeldgyrie mae andalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rodrigo Duterte: fire and fury in the PhilippinesDe la EverandRodrigo Duterte: fire and fury in the PhilippinesEvaluare: 2 din 5 stele2/5 (5)

- Can The BangsaMoro Basic Law (BBL) Succeed Where The Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) Failed?Document5 paginiCan The BangsaMoro Basic Law (BBL) Succeed Where The Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) Failed?mingming2013Încă nu există evaluări

- Is There Such Thing As Filipino Political Thought?Document7 paginiIs There Such Thing As Filipino Political Thought?Michael Cafirma0% (1)

- The Philippines Country Knowledge Strategy and Plan, 2012–2017: A Knowledge CompendiumDe la EverandThe Philippines Country Knowledge Strategy and Plan, 2012–2017: A Knowledge CompendiumÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fact Sheet On Villar ControversyDocument4 paginiFact Sheet On Villar ControversyManuel L. Quezon III50% (4)

- Presentation 3Document26 paginiPresentation 3Levi PogiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Industrial Policy in PhilippinesDocument6 paginiIndustrial Policy in PhilippinesSharon Rose GalopeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business and Its EnvironmentDocument78 paginiBusiness and Its Environmentjadey herveÎncă nu există evaluări

- Apreliminaryreportofpainthephilippines 111203183948 Phpapp02Document49 paginiApreliminaryreportofpainthephilippines 111203183948 Phpapp02Ed Villa100% (1)

- Rizal Report FinalDocument5 paginiRizal Report FinalJencelle MirabuenoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Modernization Theories of Development AnDocument6 paginiModernization Theories of Development AnAulineu BangtanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment 04 - Reflective Public Administration, Public Administration and Public AdministrationDocument6 paginiAssignment 04 - Reflective Public Administration, Public Administration and Public AdministrationLindi Van See Merwe100% (1)

- History of The Philippine Civil Service1Document17 paginiHistory of The Philippine Civil Service1Affirahs NurRaijean100% (1)

- PattonDocument3 paginiPattonDyane Garcia-AbayaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 - Romancing The Co-WorkerDocument1 pagină1 - Romancing The Co-Workerjan_abuzo0% (1)

- Political Violence in Mindanao: The State of Play in 2016Document20 paginiPolitical Violence in Mindanao: The State of Play in 2016Stratbase ADR InstituteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 9Document27 paginiChapter 9Hoài Sơn VũÎncă nu există evaluări

- Information Society An Information Is A Society Where The CreationDocument3 paginiInformation Society An Information Is A Society Where The CreationmisshumakhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evolotion of Public AdministrationDocument3 paginiEvolotion of Public AdministrationrishabhÎncă nu există evaluări

- Golden Spoon: The Never-Ending Food Price Hike in The Philippines Amidst The 21ST CenturyDocument12 paginiGolden Spoon: The Never-Ending Food Price Hike in The Philippines Amidst The 21ST CenturyJake Zuniga100% (1)

- b12926863 Simbulan Dante C PDFDocument482 paginib12926863 Simbulan Dante C PDFAngela Beatrice100% (1)

- Reaction PaperDocument2 paginiReaction PaperMariella AngobÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is The Relevance of Philippine Elections - NSTPDocument2 paginiWhat Is The Relevance of Philippine Elections - NSTPIsabel Jost SouribioÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Philippines A Global Model On Labor MigrationDocument218 paginiThe Philippines A Global Model On Labor MigrationMarlyn AmanteÎncă nu există evaluări

- National Security Perceptions of The PhilippinesDocument4 paginiNational Security Perceptions of The PhilippinesjealousmistressÎncă nu există evaluări

- The real Keynesian Theory, explained brief and simpleDe la EverandThe real Keynesian Theory, explained brief and simpleÎncă nu există evaluări

- Innovation of Gawad Kalinga - Managing Partnerships of MeaningDocument5 paginiInnovation of Gawad Kalinga - Managing Partnerships of MeaningNisco NegrosÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filipino Images of The NationDocument26 paginiFilipino Images of The NationLuisa ElagoÎncă nu există evaluări

- The COVID-19 Impact on Philippine Business: Key Findings from the Enterprise SurveyDe la EverandThe COVID-19 Impact on Philippine Business: Key Findings from the Enterprise SurveyEvaluare: 5 din 5 stele5/5 (1)

- Mindanao / Bangsamoro Autonomous Region (Barmm)Document30 paginiMindanao / Bangsamoro Autonomous Region (Barmm)Janna Grace Dela CruzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Online and Offline Political Engagement of College Students in Naga CityDocument35 paginiOnline and Offline Political Engagement of College Students in Naga CityJan Aguilar EstefaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Insight PaperDocument1 paginăInsight Paperjihye niveaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Zero HungerDocument2 paginiZero HungerfintastellaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Role of The Police in Disasters Caused by Pandemic Infectious DiseasesDocument8 paginiThe Role of The Police in Disasters Caused by Pandemic Infectious DiseasesProf. dr Vladimir M. Cvetković, Fakultet bezbednosti, Univerzitet u BeograduÎncă nu există evaluări

- Presidents and the Politics of Agency Design: Political Insulation in the United States Government Bureaucracy, 1946-1997De la EverandPresidents and the Politics of Agency Design: Political Insulation in the United States Government Bureaucracy, 1946-1997Încă nu există evaluări

- Globalization Favors Westernization: Case StudyDocument3 paginiGlobalization Favors Westernization: Case StudyMikaela GaytaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Public Finance and Resource Management (MPA) : Submitted byDocument5 paginiPublic Finance and Resource Management (MPA) : Submitted byJnana YumnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Globalization and Nation-Building in The PhilsDocument10 paginiGlobalization and Nation-Building in The Philscm pacopiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ARTICLE REVIEW: Sustaining Filipino Unity: Harnessing Indigenous Values For Moral Recovery (Proserpina Domingo Tapales & Ma. Concepcion P. Alfiler)Document4 paginiARTICLE REVIEW: Sustaining Filipino Unity: Harnessing Indigenous Values For Moral Recovery (Proserpina Domingo Tapales & Ma. Concepcion P. Alfiler)ShebaSarsosaAdlawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gawad KalingaDocument7 paginiGawad Kalingaeya_iÎncă nu există evaluări

- Policy Making ProcessesDocument22 paginiPolicy Making ProcessesBegna AbeÎncă nu există evaluări

- Niel Ronalph AbesamisDocument2 paginiNiel Ronalph AbesamisNiel Ronalph AbesamisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dynamics of Philippine PoliticsDocument40 paginiDynamics of Philippine PoliticsHarry Punzalan0% (1)

- Philippine Foreign Service Act of 1991Document56 paginiPhilippine Foreign Service Act of 1991Enuh IglesiasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Briones - Globalization, Nationalism and Public AdministrationDocument32 paginiBriones - Globalization, Nationalism and Public AdministrationMarvin Jay MusngiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1 - History: Definition, Nature, Methodology and ImportanceDocument69 paginiModule 1 - History: Definition, Nature, Methodology and ImportanceJAMIE DUAYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Wealth of Nation SummaryDocument4 paginiWealth of Nation SummaryIda Nur IzatyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Economic Development or Environmental Protection? The Dilemmas of The Developing Countries Through The Case of The PhilippinesDocument9 paginiEconomic Development or Environmental Protection? The Dilemmas of The Developing Countries Through The Case of The PhilippinesXynaÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Good Governance?Document5 paginiWhat Is Good Governance?SEDA InstituteÎncă nu există evaluări

- Strategic Management Regis 0 PDFDocument34 paginiStrategic Management Regis 0 PDFKhristine PerezÎncă nu există evaluări

- April11.2014 Dspeaker Feliciano Belmonte, Jr.'s Statement On The Divorce Bill and Possible Abortion BillDocument1 paginăApril11.2014 Dspeaker Feliciano Belmonte, Jr.'s Statement On The Divorce Bill and Possible Abortion Billpribhor2Încă nu există evaluări

- Quiz 3 AMGT-11: Name: Raven Louise Dahlen Test IDocument2 paginiQuiz 3 AMGT-11: Name: Raven Louise Dahlen Test IRaven DahlenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bidding Process For Procurement Process and DPWHPDFDocument9 paginiBidding Process For Procurement Process and DPWHPDFGerardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nego Long Quiz 12 With Basis Midterms MCQDocument6 paginiNego Long Quiz 12 With Basis Midterms MCQClephanie BuaquiñaÎncă nu există evaluări

- OWD000201 GGSN9811 Data Configuration ISSUE2.0Document91 paginiOWD000201 GGSN9811 Data Configuration ISSUE2.0ahmedsabryragheb100% (1)

- Tax Challenges Arising From DigitalisationDocument250 paginiTax Challenges Arising From DigitalisationlaisecaceoÎncă nu există evaluări

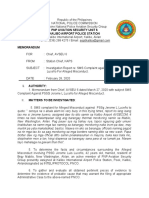

- PNP Aviation Security Unit 6 Kalibo Airport Police StationDocument3 paginiPNP Aviation Security Unit 6 Kalibo Airport Police StationAngelica Amor Moscoso FerrarisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment On Drafting & Pleading': Submitted byDocument73 paginiAssignment On Drafting & Pleading': Submitted byPuchi Sinha100% (1)

- Pengaruh Paham Liberalisme Dan Neoliberalisme Terhadap Pendidikan Islam Di Indonesia PDFDocument26 paginiPengaruh Paham Liberalisme Dan Neoliberalisme Terhadap Pendidikan Islam Di Indonesia PDFAndi Muhammad Safwan RaisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Andrew Morin and Adelaide Grandbois (Family Reunion Works)Document87 paginiAndrew Morin and Adelaide Grandbois (Family Reunion Works)Morin Family Reunions History100% (3)

- Inc 2Document19 paginiInc 2MathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- 016 Magtajas v. Pryce Properties - 234 SCRA 255Document13 pagini016 Magtajas v. Pryce Properties - 234 SCRA 255JÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nietzsche and The Origins of ChristianityDocument20 paginiNietzsche and The Origins of ChristianityElianMÎncă nu există evaluări

- De Leon Vs EsperonDocument21 paginiDe Leon Vs EsperonelobeniaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ysidro Vs PeopleDocument8 paginiYsidro Vs PeopleajdgafjsdgaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Study Note 3, Page 114-142Document29 paginiStudy Note 3, Page 114-142s4sahithÎncă nu există evaluări

- CivproDocument60 paginiCivprodeuce scriÎncă nu există evaluări

- Business and Transfer Taxation Chapter 9 Discussion Questions AnswerDocument3 paginiBusiness and Transfer Taxation Chapter 9 Discussion Questions AnswerKarla Faye LagangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Liberia Ok Physical Examination ReportcertDocument2 paginiLiberia Ok Physical Examination ReportcertRicardo AquinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- DiffusionDocument15 paginiDiffusionRochie DiezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Department of Labor: Kaiser Permanente Bridge ProgramDocument1 paginăDepartment of Labor: Kaiser Permanente Bridge ProgramUSA_DepartmentOfLaborÎncă nu există evaluări

- TWG-Findings-ABS-CBN Franchise PDFDocument40 paginiTWG-Findings-ABS-CBN Franchise PDFMa Zola EstelaÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 203610, October 10, 2016Document7 paginiG.R. No. 203610, October 10, 2016Karla KatigbakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Asn RNC TicketDocument1 paginăAsn RNC TicketK_KaruppiahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Powers of The PresidentDocument4 paginiPowers of The Presidentlabellejolie100% (1)

- DPRM Form RSD 03 A Revised 2017Document2 paginiDPRM Form RSD 03 A Revised 2017NARUTO100% (2)

- Module 1Document11 paginiModule 1Karelle MalasagaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chartering TermsDocument9 paginiChartering TermsNeha KannojiyaÎncă nu există evaluări

- ProjectDocument70 paginiProjectAshish mathew chackoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Collado v. Homeland Security Immigration Services - Document No. 10Document2 paginiCollado v. Homeland Security Immigration Services - Document No. 10Justia.comÎncă nu există evaluări