Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

The State of Nature of ThomAS HOOBESS

Încărcat de

Donasco Casinoo ChrisDescriere originală:

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

The State of Nature of ThomAS HOOBESS

Încărcat de

Donasco Casinoo ChrisDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

INTRODUCTION State of Nature is a term in political philosophy used in social contract theories to describe the hypothetical condition that

preceded governments. There must have been a time before government, and so the question is how legitimate government could emerge from such a starting position, and what are the hypothetical reasons for entering a state of society by establishing a government. THE MEANIING STATE OF NATURE IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF THOMAS HOBBES The concept of state of nature was posited by the 17th century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan and his earlier work On the Citizen. Hobbes wrote that "during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man" . In this state any person has a natural right to the liberty to do anything he wills to preserve his own life and life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short". Hobbes' view of the state of nature helped to serve as a basis for theories of international realism. THOMAS HOBBES' IDEA OF THE STATE OF NATURE'. Hobbes' idea of the State of Nature' is a logical outgrowth of his perspective of human nature and the concept of power. In Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes (1651) writes: "During the time men live without a common Power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called Warre." The condition of war led Hobbes to assert famously that life without strong central government would be "solitary, poore, brutish and short". Such is the Hobessian state of nature. While claiming man's essential nature as selfish and competitive, Hobbes propounds the case for a powerful sovereign, or Leviathan, to enforce peace and the law, substituting security for the anarchic freedom he believed human beings would otherwise experience. Hobbes prefers an absolute monarchical sovereignty, not because he believes in any inherent right of kings to rule, but because he

believed that a monarch could be invested in something approaching popular consent (Fukuyama, 1992). Hobbes' state of nature must be understood within the chain of reasoning that brought it into existence in the first place. For instance, Hobbes advances, firstly, a Theory of Human Nature in Society; he then moves on to introduce, progressively, the famous concepts of State of Nature, Right of Nature, Law of Nature, and the Social Contract (MacPherson, 1968). The last three concepts do not pertain for current purposes. Also, I will provide a critique on Hobbes' idea of the state of nature to indicate the possible limitations of his assertions.

Within the state of nature there is no injustice, since there is no law, excepting certain natural precepts, the first of which is "that every man ought to Endeavour peace, as far as he has hope of obtaining it" (Leviathan, ch. XIV); and the second is "that a man be willing, when others are so too, as far north as for peace and defense of himself he shall think it necessary, to lay down this right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men as he would allow other men against himself" (loc. cit.). From this, Hobbes develops the way out of the state of nature into civil government by mutual contracts. Hobbes described the concept in the Latin phrase bellum omnium contra omnes, (meaning war of all against all) in his work Hobbes Account For State Of Nature The extremity of Hobbes state of nature is typified as the warre of every man against every man. This one line sums up the severity of the scenario presented by Hobbes and informs why the life of man must be nasty, brutish and short. This position of Hobbes is arrived at in a systematic way that perhaps makes him the father of political science. Such a scientific approach is none more evident than in his invocation of Galileos theory of the conservation of motion: that whatever is in motion will remain so until halted by some other force. In terms of

human agency Hobbes viewed motion as producing delight or displeasure within us. Obviously we will desire those pleasure or delight inducing motions rather than painful or even contemptible ones and so are in a fixed search for felicity and aversion to pain. Furthermore, Hobbes saw men as roughly equal. Although one man may be physically stronger than another and one smarter than another, these differences do not produce any sort of natural hierarchy. For the stronger man may dominate the weaker, but the weaker may take up arms or join with others in confederacy thus negating the strong mans apparent advantage. In terms of intellectual equality Hobbes describes how any given man will often believe himself to be more wise than most others. Yet it cannot be logically possible for most men to be more wise than most others. In fact Hobbes points out that if each man thinks himself wiser, then he must be contented with his share and there is no greater signe of the equal distribution of any thing, than that every man is contented with his share. Our search for felicity coupled with us being relatively equal in terms of capabilities sets us on a collision course. We want to fulfill our desires, but our neighbours want to fulfill theirs too. If we have the same tangible desire and that object is in scarcity then we will be on a path to confrontation. This confrontation puts our ultimate end or strongest desire (self preservation) in great jeopardy and if our opponent is successful and subordinates, kills or takes what we possess, the same misfortune may soon await him. The problems associated with this search for felicity and aversion of the undesired does not end here though. For there is also the consideration of potential enemies. For man X may desire a set piece of land and take it peacefully, but his knowing that all else is equal could give him reason to suspect that man Y or Z may have a desire to take this land, even though they have made no such expression of the will. In such a case he may make a pre emptive strike to eliminate what are merely potential enemies. It even matters not the status of either Y or Z. Y may be a man of many possessions and prestige and so X has

reason to suspect him of wanting to further these attributes. Z may be a man with nothing and so X knows he also has motive to take his land and so in the state of nature no man is safe, not the figurative prince nor pauper. Yet still this is not all, for the picture painted becomes even worse if we consider those who simply enjoy conquest or the suffering of others. With these people added to the equation even those content with what they have must act like the worst kind of tyrant in order to try and secure themselves. Acting for ones security for Hobbes is really the only right we have in the state of nature. Self preservation is the only right (or perhaps obligation is more apt) independent of government. For he saw the state as being prior to any kind of virtue which coupled with the picture painted informs why he thinks the state of nature to be a state of war. Finally, Hobbes gives a list of laws of nature. These laws essentially come down to the fact that it is rational for us to seek peace in the state of nature, which would apparently conflict with the entire scenario he has so far presented. However the laws of nature are an expression of collective rationality were as our behaviour described in the state of nature is an example of individual rationality. While it may be rational to seek peace this is only possible if everyone else seeks peace and given the suspicious nature of man out with the state and the lack of mechanisms (a commonwealth) available to achieve this end, this expression of collective rationality simply cannot be made. CONCLUSION The theory of Hobbes makes us to consider what life would be like in a state of nature, that is, a condition without government. Perhaps we would imagine that people might fare best in such a state, where each decides for herself how to act, and is judge, jury and executioner in her own case whenever disputes ariseand that at any rate, this state is the appropriate baseline against which to judge the justifiability of political arrangements. Hobbes terms this situation the condition of mere nature, a state of perfectly private judgment, in which there is no agency

with recognized authority to arbitrate disputes and effective power to enforce its decisions.

REFERENCE Hobbes Thomas. Leviathan. 1651, Edwin Curley (Ed.) 1994. Hackett Publishing Baumgold, D., (1988), Hobbes's Political Thought: Cambridge University Press.

VEERITAS UNIVERSITY ABUJA (THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA) OBEHIE CAMPUS ABIA STATE DISCUSS THE STATE OF NATURE IN THE PHILOSPHY OF THAMOS HOBBES ASSIGMENT ON: LOGIC AND PHILOSOPHY (GES 1032) PRESENTED TO: REV.FR.DR. USOH (LECTURER) DEPARTMENTOF SOCIAL SCIENCES BY NAME: CHRIS-WORLU IGWUGWUM MATRIC NO: VUG/POL/11/323 DATE: 21TH June, 2012

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Hobbes's Moral and Political Philosophy: The Philosophical ProjectDocument10 paginiHobbes's Moral and Political Philosophy: The Philosophical ProjectShubhankar ThakurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hobbes, Locke and RousseauDocument13 paginiHobbes, Locke and RousseauasadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political PhilosophyDocument2 paginiPolitical PhilosophySepiNsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit-6 Thomas HobbesDocument16 paginiUnit-6 Thomas Hobbesshekar6886Încă nu există evaluări

- Land Administration In Urhobo Division Under Colonial Rule 1935 – 1960De la EverandLand Administration In Urhobo Division Under Colonial Rule 1935 – 1960Încă nu există evaluări

- Social Contract Theory 2Document2 paginiSocial Contract Theory 2Amandeep Singh0% (1)

- Contrasting The Idea Social Contract of Hobbes and RousseauDocument5 paginiContrasting The Idea Social Contract of Hobbes and RousseauVicky CagayatÎncă nu există evaluări

- Introduction To The Social Contract TheoryDocument3 paginiIntroduction To The Social Contract TheoryIbadullah RashdiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Concept of Rights 1Document6 paginiConcept of Rights 1nikhil pathakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Scoial Contract Theory AssignmentDocument6 paginiScoial Contract Theory Assignmentlandry Nowaruhanga100% (1)

- State of NatureDocument4 paginiState of NatureDan DavisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Locke Theory of PropertyDocument22 paginiLocke Theory of PropertyPhilem Ibosana Singh100% (1)

- Rousseau WorksDocument13 paginiRousseau WorksbalalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Questions On Mill, Bentham and RousseauDocument9 paginiQuestions On Mill, Bentham and RousseauShashank Kumar SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- State and Its OriginDocument21 paginiState and Its Originzunayed islam prantoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Vi Sem-Ba Pol Sc-Core Course-Modern Political ThoughtDocument66 paginiVi Sem-Ba Pol Sc-Core Course-Modern Political Thoughtvishal rajputÎncă nu există evaluări

- Viden Io Delhi University Ba Pol SC Hons Notes State PDFDocument23 paginiViden Io Delhi University Ba Pol SC Hons Notes State PDFChelsi KukretyÎncă nu există evaluări

- REALISMDocument6 paginiREALISMGIRISHA THAKURÎncă nu există evaluări

- 26 Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1770 A.D.) : Scanned With CamscannerDocument20 pagini26 Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1770 A.D.) : Scanned With CamscannerShaman KingÎncă nu există evaluări

- Analysis of The Theory of Social Contract by Thomas HobbesDocument5 paginiAnalysis of The Theory of Social Contract by Thomas HobbesGYAN ALVIN ANGELO BILLEDOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Document 63Document10 paginiDocument 63Guddu SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legitimacy 1Document7 paginiLegitimacy 1Yash TiwariÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5 Nature and Characteristics of StateDocument31 pagini5 Nature and Characteristics of StateAdryanisah AanisahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women in The National MovementDocument6 paginiWomen in The National Movementshoan maneshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Natural Evolution in The Growth of The Behavioral ApproachDocument3 paginiNatural Evolution in The Growth of The Behavioral ApproachRJ SalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1-Introduction and Research Methodology A.: A Theory of Justice by John RowlsDocument21 paginiChapter 1-Introduction and Research Methodology A.: A Theory of Justice by John RowlsIshwarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hobbes On Human NatureDocument2 paginiHobbes On Human Naturea967tÎncă nu există evaluări

- John Locke-Political ScienceDocument19 paginiJohn Locke-Political ScienceDr-Kashif Faraz AhmedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit-5 Niccolo Machiavelli PDFDocument9 paginiUnit-5 Niccolo Machiavelli PDFSomi DasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mills LibertyDocument4 paginiMills LibertyRahul JensenÎncă nu există evaluări

- Classical and Liberal Theories On Human NatureDocument41 paginiClassical and Liberal Theories On Human NatureChristine Annmarie Tapawan100% (1)

- Lenin Imperialism CritDocument18 paginiLenin Imperialism Critchris56aÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rousseau and The Social Contract TraditionDocument5 paginiRousseau and The Social Contract TraditionFiqh VredianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nature of StateDocument11 paginiNature of StatePrashanthi Gadireddy100% (1)

- Concept of State and NationDocument4 paginiConcept of State and NationM Vijay AbrajeedhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Matriarchal Theory Patriarchal TheoryDocument4 paginiMatriarchal Theory Patriarchal Theoryunaas fatima100% (1)

- 8a. Theories of SoverreigntyDocument27 pagini8a. Theories of SoverreigntyRohit Mohan0% (1)

- International Political Economy PDFDocument5 paginiInternational Political Economy PDFsalmanyz6Încă nu există evaluări

- Article Shared ByDocument12 paginiArticle Shared ByMohammad HaroonÎncă nu există evaluări

- 05-Espuelas v. People G.R. No. L-2990 December 17, 1951Document3 pagini05-Espuelas v. People G.R. No. L-2990 December 17, 1951Jopan SJÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Concept of SovereigntyDocument22 paginiThe Concept of SovereigntyAanchal SrivastavaÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is StateDocument3 paginiWhat Is StateSyed Mohsin Mehdi TaqviÎncă nu există evaluări

- State and Theories of State OriginDocument4 paginiState and Theories of State Originjisavo6170Încă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 1 Nature Scope and SignificanceDocument41 paginiChapter 1 Nature Scope and SignificanceA To ZÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aristotle's View of PoliticsDocument5 paginiAristotle's View of PoliticsJerico CalawanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Marxist Theory of LawDocument12 paginiMarxist Theory of LawAngel StephensÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rousseau General Will-1Document5 paginiRousseau General Will-1Ammara RiazÎncă nu există evaluări

- Forms of Social Life, InteractionDocument27 paginiForms of Social Life, InteractionVidhi BansalÎncă nu există evaluări

- John LockeDocument3 paginiJohn LockeWilliamLinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Theory of Separation of PowersDocument24 paginiTheory of Separation of PowersRewant MehraÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is Liberty?: Two Concepts of LibertyDocument8 paginiWhat Is Liberty?: Two Concepts of LibertyHardik Jain100% (1)

- Aristotle's GovernmentDocument4 paginiAristotle's GovernmentAzizul Hakim B 540Încă nu există evaluări

- Analyzing Social Contract Theory of - Hobbes, Locke and RousseauDocument10 paginiAnalyzing Social Contract Theory of - Hobbes, Locke and RousseauDeependra singh RatnooÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rousseau: Ivan Paul ManaligodDocument28 paginiRousseau: Ivan Paul ManaligodIvanPaulManaligodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political Science ResubmissionDocument15 paginiPolitical Science ResubmissionThe DOD Band TNNLS, TrichyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Socio 501Document6 paginiSocio 501Medemkaba I Kichu100% (1)

- Western Political ThoughtDocument7 paginiWestern Political ThoughtShreky D' OGreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Political ScienceDocument105 paginiPolitical ScienceDeepanshu Gupta100% (1)

- Approach To Political ScienceDocument17 paginiApproach To Political ScienceRandy Raj OrtonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) : SynopsisDocument4 paginiThomas Hobbes (1588-1679) : SynopsisanisÎncă nu există evaluări

- South African and Nigerian System of GovernnanceDocument5 paginiSouth African and Nigerian System of GovernnanceDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Write On Economic Resources: An Assignment On Entreprenuer (Edc2021)Document4 paginiWrite On Economic Resources: An Assignment On Entreprenuer (Edc2021)Donasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Enumerate The Contribution of Business To The Nigeria EconomyDocument3 paginiEnumerate The Contribution of Business To The Nigeria EconomyDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Veritas University Abuja, Obehie Campus, Abia State, 23 Nov, 2012Document1 paginăVeritas University Abuja, Obehie Campus, Abia State, 23 Nov, 2012Donasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- What Is The Meaning of Economic ResourcesDocument5 paginiWhat Is The Meaning of Economic ResourcesDonasco Casinoo Chris50% (4)

- Type of Punctuaction MarksDocument2 paginiType of Punctuaction MarksDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law John AbiagomDocument4 paginiLaw John AbiagomDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Request For ExeatDocument1 paginăRequest For ExeatDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

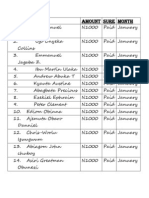

- Names Amount Sure MonthDocument4 paginiNames Amount Sure MonthDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- PandefDocument1 paginăPandefDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Letter of Appeal For Changing of CourseDocument2 paginiLetter of Appeal For Changing of CourseDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- LetterDocument1 paginăLetterDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Items Price: An Estimate Cost To Serve 2,000 Persons During The Burial of Late Rev. Canon E.C OguDocument2 paginiItems Price: An Estimate Cost To Serve 2,000 Persons During The Burial of Late Rev. Canon E.C OguDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- PublicationsDocument2 paginiPublicationsDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Survey MethodDocument4 paginiSurvey MethodDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Macosx Photoshop Windows 7 Skype Adobe Flash Player Internet ExplorerDocument2 paginiMacosx Photoshop Windows 7 Skype Adobe Flash Player Internet ExplorerDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- The History of DiplomacyDocument4 paginiThe History of DiplomacyDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- STRUCTURAL SYSTEM ANALYSIS Here All Political Parties Can Be Compared inDocument3 paginiSTRUCTURAL SYSTEM ANALYSIS Here All Political Parties Can Be Compared inDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- To Nit by John LegendDocument1 paginăTo Nit by John LegendDonasco Casinoo ChrisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nathan e Lensch vs. Sophia Rutschow 14-3-03127-0Document165 paginiNathan e Lensch vs. Sophia Rutschow 14-3-03127-0Eric YoungÎncă nu există evaluări

- Obo Citcha 2022Document21 paginiObo Citcha 2022Carl Malone TolentinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bar Qs ('09-'12)Document39 paginiBar Qs ('09-'12)Joy DalesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sample Chart MMI Human DesignDocument1 paginăSample Chart MMI Human DesignThe TreQQerÎncă nu există evaluări

- Service QuotationDocument4 paginiService Quotationkranthimahesh999Încă nu există evaluări

- Case Study 3Document3 paginiCase Study 3Pavitra ShivhareÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 4 2021 NteboDocument16 paginiChapter 4 2021 NteboNaya Naledi MokoanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ryun Williams ContractDocument16 paginiRyun Williams ContractColoradoan100% (1)

- Ignou ListDocument27 paginiIgnou ListAjay ReddyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Report Kutto 7691920-4114879Document1 paginăReport Kutto 7691920-4114879Enock K KuttoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Law QDocument7 paginiLaw Qshakhawat HossainÎncă nu există evaluări

- Duty of Care of SchoolsDocument12 paginiDuty of Care of SchoolsDonn Tantuan100% (1)

- Lavadia vs. Heirs of LunaDocument11 paginiLavadia vs. Heirs of LunaRomy Ian LimÎncă nu există evaluări

- Draft MoaDocument11 paginiDraft MoakhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Oblicon Midterms L1ADocument3 paginiOblicon Midterms L1AKaye Ann MalaluanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 9 - Documentary Evidence: 9.1 Primary and Secondary EvidenceDocument49 paginiChapter 9 - Documentary Evidence: 9.1 Primary and Secondary EvidenceAnis FirdausÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rape Under Art. 266-ADocument2 paginiRape Under Art. 266-ALesterÎncă nu există evaluări

- RR 8-2007Document2 paginiRR 8-2007naldsdomingoÎncă nu există evaluări

- GR No. 3962 US V. LING SU FANDocument14 paginiGR No. 3962 US V. LING SU FANClaire SalcedaÎncă nu există evaluări

- BL - Corporation CodeDocument25 paginiBL - Corporation CodePrincessAngelaDeLeon0% (1)

- Camaso Vs TSM Shipping - JBernabe - Rule46 - Docket FeesDocument7 paginiCamaso Vs TSM Shipping - JBernabe - Rule46 - Docket Feessandra mae bonrustroÎncă nu există evaluări

- Anthony Pusateri, Jr. v. Frank C. Johnston, 398 F.2d 327, 3rd Cir. (1968)Document3 paginiAnthony Pusateri, Jr. v. Frank C. Johnston, 398 F.2d 327, 3rd Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lesson Plan in Teaching EssayDocument12 paginiLesson Plan in Teaching EssayMelba O. Cruz100% (1)

- Fort Bonifacio Vs CIR DigestDocument3 paginiFort Bonifacio Vs CIR Digestminri72150% (4)

- NegotiationDocument30 paginiNegotiationvinodshukla25Încă nu există evaluări

- California Standard Lease Agreement Residential 2016-10-14Document10 paginiCalifornia Standard Lease Agreement Residential 2016-10-14Jè AreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Warning LetterDocument4 paginiWarning LetterHira RazaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bank Kerjasama Rakyat Malaysia BHD V MME Realty & ManagDocument13 paginiBank Kerjasama Rakyat Malaysia BHD V MME Realty & ManagNurul JannahÎncă nu există evaluări

- in Re: Designation of Judge Rodolfo U. Manzano As Member of The Ilocos Norte Provincial Committee On JusticeDocument2 paginiin Re: Designation of Judge Rodolfo U. Manzano As Member of The Ilocos Norte Provincial Committee On JusticeMichelle FajardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gaso Transport Services V Obene Ealr 1990-1994 Ea 88Document12 paginiGaso Transport Services V Obene Ealr 1990-1994 Ea 88Tumuhaise Anthony Ferdinand100% (1)