Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Experimental Research Design

Încărcat de

AmitSolankiDrepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Experimental Research Design

Încărcat de

AmitSolankiDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH DESIGN

EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH

One of the most important things for you to learn

in this course is the difference between

correlational research and experimental

research. Like correlational

research, experimental research concerns

relationships between variables. Unlike

correlational research, however, experimental

research provides strong evidence for causal

interpretations. Here we will focus on the two

most important features of experimental

research.

NON EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH

DESIGN

In non experimental research, the researcher starts

from the effect or outcome and attempts to determine

causation.

Nonexperimental research involves observing and

measuring things as they are. Naturalistic observation,

interview, survey, case history, and psychometric scales

are some of the methods used when it is not possible

or unethical to manipulate an independent variable.

Nonexperimental research is used to provide solutions

to problems. Nonexperimental research can add to

what we know by common sense because we can test

our beliefs to see how true they are.

QUASI-EXPERIMENTAL

Quasi-Experiments

The prefix quasi means, in essence, sort of. So

a quasi-experiment is a sort of

experiment. Specifically, a quasi-experiment is a

study that includes a manipulated independent

variable but lacks important controls (e.g., random

assignment), or a study that lacks a manipulated

independent variable but includes important

controls. So a quasi-experiment has some features

of a well conducted experiment but not others.

Types of Quasi-Experiments

Non-Equivalent Groups Design

A non-equivalent groups design includes an

existing group of participants who receive a

treatment and another existing group of

participants to serve as a control or comparison

group. Participants are not randomly assigned to

conditions, but rather are assigned to the

treatment or control conditions along with all the

others in their existing group.

Pretest-Posttest Design

In a pretest-posttest design, a single group of

participants is measured on the dependent variable both

before and after the manipulation of the independent

variable. Imagine that a group of 100 sixth graders is

given a test of their attitudes toward drugs. This is the

pretest. Then, a week later, a police officer comes to

school and presents an anti-drug program (complete with

cool decorated car and performing police dog). This is

the treatment. Then, in another week, the students are

given another test of their attitudes toward drugs. This is

the posttest. Obviously, the substantive question here is

whether the students attitudes toward drugs change

after being presented with the anti-drug program.

Interrupted Time-Series Designs

A time series is simply a set of measurements

of a variable taken at various points in

time. For example, we could measure the

moods of the students in our class each day

throughout the semester, and we could see

how peoples moods changed (or did not

change) over time. In an interrupted time-

series design, a time series like this (the

dependent variable) is interrupted (usually

near the middle) by the manipulation of the

independent variable.

UNSUITABILITY OF EXPERIMENTAL

RESEARCH DESIGN

* Elimination of extraneous variables is not

always possible.

* Experimental situation may not relate to the

real world.

* It may be unethical or impossible to randomly

assign people to groups.

LIMITATIONS

The first is that sometimes you cannot do an

experiment because you cannot manipulate the

independent variable, either for practical or ethical

reasons. For example, if you are interested in the

effects of a persons culture on their tendency to help

strangers, you cannot do an experiment. Why

not? You cannot manipulate a persons culture. Or if

you are interested in how damage to a certain part of

the brain affects behavior, you cannot do an

experiment. Why not? You cannot go around

damaging peoples brains to see what happens. In

such cases, correlational research is the only

alternative.

The second limitation of experimental research is that

sometimes controlling extraneous variables means

creating situations that are somewhat artificial. A good

example is provided research on the effect of smiling

on first impressions. To control extraneous variables,

people are typically brought into a laboratory and

asked standard questions about a small number of

posed stimulus photographs. It is legitimate to ask,

however, whether the effect of smiling is likely to be

the same out in the "real world" where people are

actually interacting with each other. For a good

discussion of why this is not always a problem, though,

see Stanovich's (2007) discussion of the "artificiality

criticism" of psychological research.

SOME OTHER LIMITATIONS

Uses casual relationships that may be bias.

Scientist manipulates values so they may not

be making a completely objective experiment.

People can be influenced by what they see

around them and may give answers that they

think the researcher wants to hear rather than

how they think and feel on a subject.

A CASE STUDY USING EXPERIMENTAL

DESIGN

Problem: Researchers wanted to evaluate a

family-participation drug prevention program

in the Boys and Girls Clubs. Four clubs were

purposively selected to receive the program

because they had directors who would

strongly support the promotion of family

involvement and would give the program

coordinator the flexibility to work in

nontraditional ways to encourage family

participation.

A Solution: Other Boys and Girls Clubs that

were similar on socioeconomic and other

demographic variables to the family-

participation program clubs were selected as

comparison groups.

A Drawback to the Solution: Children in the

family-participation program were about a

quarter of a year younger, on the average, than

those in the comparison groups. While all groups

were predominantly African American, there

were differences in the second most frequent

racial/ethnic groups with differences in the

Hispanic and Caucasian mix. There were

differences in the gender composition of the

groups (e.g., 35% female in the family-

participation clubs and 41% female in the control

clubs).

Validity in Experimental Design

Internal validity: Internal validity tries to

examine whether the observed effect on a

dependent variable is actually caused by the

independent variables in question.

External validity: External validity refers to the

generalization of the results of an experiment.

The concern is whether the result of an

experiment can be generalized beyond the

experimental situations

Threats to internal validity

Ambiguous temporal precedence

Lack of clarity about which variable occurred first may yield

confusion about which variable is the cause and which is the

effect.

Confounding

A major threat to the validity of causal inferences

is confounding: Changes in the dependent variable may rather

be attributed to the existence or variations in the degree of a

third variable which is related to the manipulated variable.

Where spurious relationships cannot be ruled out, rival

hypotheses to the original causal inference hypothesis of the

researcher may be developed.

Selection bias

Selection bias refers to the problem that, at pre-

test, differences between groups exist that may

interact with the independent variable and thus be

'responsible' for the observed outcome.

Researchers and participants bring to the

experiment a myriad of characteristics, some

learned and others inherent. For example, sex,

weight, hair, eye, and skin color, personality, mental

capabilities, and physical abilities, but also attitudes

like motivation or willingness to participate.

History

Events outside of the study/experiment or between

repeated measures of the dependent variable may

affect participants' responses to experimental

procedures. Often, these are large scale events

(natural disaster, political change, etc.) that affect

participants' attitudes and behaviors such that it

becomes impossible to determine whether any

change on the dependent measures is due to the

independent variable, or the historical event.

Maturation

Subjects change during the course of the experiment or

even between measurements. For example, young

children might mature and their ability to concentrate

may change as they grow up. Both permanent changes,

such as physical growth and temporary ones like fatigue,

provide "natural" alternative explanations; thus, they may

change the way a subject would react to the independent

variable. So upon completion of the study, the researcher

may not be able to determine if the cause of the

discrepancy is due to time or the independent variable.

Instrument change (instrumentality

The instrument used during the testing process can

change the experiment. This also refers to observers

being more concentrated or primed, or having

unconsciously changed the criteria they use to make

judgments. This can also be an issue with self-report

measures given at different times. In this case the impact

may be mitigated through the use of retrospective

pretesting. If any instrumentation changes occur, the

internal validity of the main conclusion is affected, as

alternative explanations are readily available.

Experimenter bias

Experimenter bias occurs when the individuals who

are conducting an experiment inadvertently affect

the outcome by non-consciously behaving in

different ways to members of control and

experimental groups. It is possible to eliminate the

possibility of experimenter bias through the use

of double blind study designs, in which the

experimenter is not aware of the condition to which

a participant belongs.

Repeated testing (also referred to as testing

effects)

Repeatedly measuring the participants may lead to

bias. Participants may remember the correct

answers or may be conditioned to know that they

are being tested. Repeatedly taking (the same or

similar) intelligence tests usually leads to score

gains, but instead of concluding that the underlying

skills have changed for good, this threat to Internal

Validity provides good rival hypotheses.

Threats to external validity

Reactive effects of experimental

arrangements: It is difficult to generalize to

non-experimental settings if the effect was

attributable to the experimental arrangement

of the research.

Multiple treatment interference: As multiple

treatments are given to the same subjects, it

is difficult to control for the effects of prior

treatments.

Situation: All situational specifics (e.g. treatment

conditions, time, location, lighting, noise, treatment

administration, investigator, timing, scope and extent

of measurement, etc. etc.) of a study potentially limit

generalizability.

Aptitudetreatment Interaction: The sample may have

certain features that may interact with the

independent variable, limiting generalizability. For

example, inferences based on comparative

psychotherapy studies often employ specific samples

(e.g. volunteers, highly depressed, no comorbidity).

The environment at the time of test may be

different from the environment of the real world

where these results are to be generalized.

Pre-test effects: Individuals who were pretested

might be less or more sensitive to the

experimental variable or might have "learned"

from the pre-test making them unrepresentative

of the population who had not been pre-tested.

Post-test effects: If cause-effect relationships can

only be found when post-tests are carried out,

then this also limits the findings because of the

pre-test estimation.

Treatment at the time of the test may be

different from the treatment of the real world.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- 75 Takeaways From Expert Secrets BookDocument16 pagini75 Takeaways From Expert Secrets BookIacob Ioan-Adrian80% (5)

- Methods of Data Collection Research MethodologyDocument44 paginiMethods of Data Collection Research MethodologyDr. Daniel C100% (1)

- The Great Amherst Mystery by Walter Hubbell PDFDocument228 paginiThe Great Amherst Mystery by Walter Hubbell PDFPradyut Tiwari100% (1)

- 5.research DesignDocument16 pagini5.research DesignManjunatha HRÎncă nu există evaluări

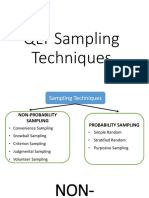

- SamplingDocument17 paginiSamplingManika GuptaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abm - PR2 (Carandang, Quijano, de Castro, Hernandez, Perfinian)Document43 paginiAbm - PR2 (Carandang, Quijano, de Castro, Hernandez, Perfinian)Angelica CarandangÎncă nu există evaluări

- Probability and Non ProbabilityDocument2 paginiProbability and Non Probabilitychandu_jjvrpÎncă nu există evaluări

- English 10 - F2F 6Document5 paginiEnglish 10 - F2F 6Daniela DaculanÎncă nu există evaluări

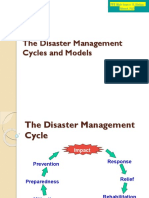

- 3 The Disaster Management Cycle and Models 1Document35 pagini3 The Disaster Management Cycle and Models 1triratna100% (1)

- Formative Assessment vs. Summative AssessmentDocument12 paginiFormative Assessment vs. Summative AssessmentZin Maung TunÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter 3 Preliminary Information Gathering and Problem DefinitionDocument15 paginiChapter 3 Preliminary Information Gathering and Problem Definitionnoor marliyahÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reinventing OrganizationDocument379 paginiReinventing OrganizationАлина ЛовицкаяÎncă nu există evaluări

- CRSHS Monitoring Tool in Guidance and CounselingDocument2 paginiCRSHS Monitoring Tool in Guidance and Counselingmaria luz100% (2)

- Chapter 10: Nature of Research Design and MethodsDocument10 paginiChapter 10: Nature of Research Design and MethodsVero SteelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Population - RESEARCHDocument21 paginiPopulation - RESEARCHvrvasukiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Correlational ResearchDocument22 paginiCorrelational ResearchAxel Jilian BumatayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Methods of Data CollectionDocument14 paginiMethods of Data CollectionMaruthi100% (1)

- Research Design and ApproachsDocument69 paginiResearch Design and ApproachsSudharani B BanappagoudarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Tools and Techniques in Evaluation 2Document30 paginiTools and Techniques in Evaluation 2Pratheesh PkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experimental Designs: Submitted By-Avishi Deepika Gagan GauriDocument22 paginiExperimental Designs: Submitted By-Avishi Deepika Gagan GauriDeepika RoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leadership Study BenchmarkingDocument7 paginiLeadership Study BenchmarkingPaula Jane MeriolesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Assignment On Tools For Data Collection by Kamini23Document6 paginiAssignment On Tools For Data Collection by Kamini23kamini Choudhary100% (1)

- Formative and Summative EvaluationDocument12 paginiFormative and Summative EvaluationWellington MudyawabikwaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 9 Transformative and MultiphaseDocument9 pagini9 Transformative and MultiphaseAC BalioÎncă nu există evaluări

- Quantitative Research DesignDocument2 paginiQuantitative Research DesignJustine NyangaresiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Summative EvaluationDocument22 paginiSummative EvaluationsonaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The Variables: Variable Is That The Meaning of Each Is Implied byDocument12 paginiThe Variables: Variable Is That The Meaning of Each Is Implied byEmily JamioÎncă nu există evaluări

- 5.2 Content Limitation, Organization EtcDocument12 pagini5.2 Content Limitation, Organization EtcAjay MagarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test of Intelligence Apttitude and InterestDocument20 paginiTest of Intelligence Apttitude and InterestSuraj Nirmalkar100% (1)

- Reaserch MethdologyDocument132 paginiReaserch Methdologymelanawit100% (1)

- Creating QuestionnaireDocument53 paginiCreating QuestionnaireEISEN BELWIGANÎncă nu există evaluări

- Master Plan, Course Plan, Unit Plan: Soumya Ranjan ParidaDocument65 paginiMaster Plan, Course Plan, Unit Plan: Soumya Ranjan ParidaBeulah DasariÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experimental ResearchDocument22 paginiExperimental ResearchCuteepie Sucheta MondalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Experimental Research DesignDocument3 paginiExperimental Research Designnabeel100% (1)

- Experemental Research 2Document14 paginiExperemental Research 2Dark XXIVÎncă nu există evaluări

- Educational Objectives: Presented By:-Priyanka Bhavsar 1 Year M.SC NursingDocument22 paginiEducational Objectives: Presented By:-Priyanka Bhavsar 1 Year M.SC Nursingpriyanka bhavsarÎncă nu există evaluări

- DataanalysisDocument28 paginiDataanalysisValliammalShanmugam100% (1)

- Lecture Plan Apptitude TestDocument4 paginiLecture Plan Apptitude TestDileepSinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Chapter IIIDocument23 paginiChapter IIIilham0% (1)

- Programmed InstructionDocument14 paginiProgrammed InstructionAnilkumar JaraliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Sampling TechniquesDocument17 paginiSampling TechniquesRochelle NayreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Evaluation of Educational Programs in Nursing Course andDocument18 paginiEvaluation of Educational Programs in Nursing Course andsaritha OrugantiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Teaching and LearningDocument29 paginiTeaching and LearningGeok Hong 老妖精Încă nu există evaluări

- Gantt Chart With ExampleDocument1 paginăGantt Chart With ExamplefaeeezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Writing Chapter 5Document3 paginiWriting Chapter 5Marcela Lye Jamora100% (1)

- Decision Making-Decentralization Basic Goals of DecentralizationDocument18 paginiDecision Making-Decentralization Basic Goals of DecentralizationValarmathiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leadership StylesDocument20 paginiLeadership Stylessanthosh prabhu mÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research ObjectiveDocument16 paginiResearch ObjectiveMuhammad AbdurrahmanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Basic Principles of Experimental DesignsDocument2 paginiBasic Principles of Experimental DesignsAnonymous AuvmxB100% (2)

- Community-Based Disaster Preparedness PlanDocument11 paginiCommunity-Based Disaster Preparedness PlanMohit MalhotraÎncă nu există evaluări

- University Research Ethics CommitteeDocument2 paginiUniversity Research Ethics CommitteeKyle Alexander OzoaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Consecutive Sampling: Definition: Non-Probability Sampling Convenience Sampling SampleDocument3 paginiConsecutive Sampling: Definition: Non-Probability Sampling Convenience Sampling SampleSureshÎncă nu există evaluări

- Programmed Instruction 2003Document7 paginiProgrammed Instruction 2003Prashanth Padmini VenugopalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Programmed LearningDocument12 paginiProgrammed LearningRajakumaranÎncă nu există evaluări

- Test ScoringDocument9 paginiTest ScoringArsal AliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Discussion of Experimental Results and Stimulus VariationDocument16 paginiDiscussion of Experimental Results and Stimulus VariationNorliyana Ali89% (9)

- Speech On Advantage and Disadvantages of Online ExamsDocument2 paginiSpeech On Advantage and Disadvantages of Online ExamsBindiya Goyal100% (1)

- Inquiries - Capstone - Research InstrumentsDocument5 paginiInquiries - Capstone - Research InstrumentsWynne Cassandra JoverÎncă nu există evaluări

- Item AnalysisDocument2 paginiItem Analysisapi-26570979Încă nu există evaluări

- A Descriptive Study To Assess The Knowledge On Effects of Smoking and Alcoholism Among Adolescent Boys at ChennaiDocument3 paginiA Descriptive Study To Assess The Knowledge On Effects of Smoking and Alcoholism Among Adolescent Boys at ChennaiInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- ScalesDocument41 paginiScalesBelbi Mol100% (1)

- InterviewingDocument21 paginiInterviewingkirovdustÎncă nu există evaluări

- Types of EvaluationDocument13 paginiTypes of EvaluationPavithra PÎncă nu există evaluări

- DBU Guidelines For Thesis AyurvedaDocument14 paginiDBU Guidelines For Thesis AyurvedaNitin100% (1)

- Data PresentationDocument15 paginiData PresentationAesthethic ArcÎncă nu există evaluări

- 21.cpsy.34 Research MethodsDocument14 pagini21.cpsy.34 Research MethodsVictor YanafÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 2Document23 paginiModule 2hafizamanzoor44Încă nu există evaluări

- Accuscan Form 26720Document2 paginiAccuscan Form 26720isimon234Încă nu există evaluări

- Unit 8 LeadershipDocument22 paginiUnit 8 LeadershipNgọc VõÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mall Atmospherics Interaction EffectsDocument8 paginiMall Atmospherics Interaction EffectsLuis LancaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cultural Barriers of CommunicationDocument2 paginiCultural Barriers of CommunicationAndré Rodríguez RojasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning: Pogil and The Pogil ProjectDocument12 paginiProcess-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning: Pogil and The Pogil ProjectainuzzahrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Formal PresentationDocument5 paginiFormal PresentationMuhammad Ali Khalid100% (1)

- Eicher Motors Project ..SalesDocument11 paginiEicher Motors Project ..SalesVivek SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arlene Religion 8Document1 paginăArlene Religion 8Vincent A. BacusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reflection PaperDocument7 paginiReflection Paperapi-320114472Încă nu există evaluări

- Title Defense For MastersDocument15 paginiTitle Defense For MastersDauntless KarenÎncă nu există evaluări

- 10 Ways To Improve Your Speech DeliveryDocument12 pagini10 Ways To Improve Your Speech DeliveryHappyNeversmilesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unit 1Document21 paginiUnit 1rammar147Încă nu există evaluări

- The Zone of Proximal Development As An Overarching Concept A Framework For Synthesizing Vygotsky S TheoriesDocument14 paginiThe Zone of Proximal Development As An Overarching Concept A Framework For Synthesizing Vygotsky S Theoriesannaliesehatton3011Încă nu există evaluări

- Presentation Lesson PlanDocument4 paginiPresentation Lesson Planapi-306805807Încă nu există evaluări

- It's Not What You Think. It's What You Know.: Inside The Counterintuitive World of Trend FollowersDocument3 paginiIt's Not What You Think. It's What You Know.: Inside The Counterintuitive World of Trend FollowersfrgÎncă nu există evaluări

- Candidate Assessment Activity: Written Responses To QuestionsDocument2 paginiCandidate Assessment Activity: Written Responses To Questionsmbrnadine belgica0% (1)

- RCOSDocument3 paginiRCOSapi-3695543Încă nu există evaluări

- 4 DLL-BPP-Perform-Basic-Preventive-MeasureDocument3 pagini4 DLL-BPP-Perform-Basic-Preventive-MeasureMea Joy Albao ColanaÎncă nu există evaluări

- DLL For COT 2ndDocument3 paginiDLL For COT 2ndAllan Jovi BajadoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Icpna Lesson Plan Daniel Escriba MET3Document3 paginiIcpna Lesson Plan Daniel Escriba MET3Estefany RodriguezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Demo Tool For Teaching InternshipDocument3 paginiDemo Tool For Teaching InternshipRica TanoÎncă nu există evaluări

- THESIS REVIEW REPORT - M. Hasbi Ghozali Nizamuddin 3B KeperawatanDocument10 paginiTHESIS REVIEW REPORT - M. Hasbi Ghozali Nizamuddin 3B KeperawatanAnonymous kVZb4Q4iÎncă nu există evaluări

- Research and Practice (7 Ed.) 'Cengage, Australia, Victoria, Pp. 103-121Document18 paginiResearch and Practice (7 Ed.) 'Cengage, Australia, Victoria, Pp. 103-121api-471795964Încă nu există evaluări