Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Galen

Încărcat de

Carlos José Fletes G.Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Galen

Încărcat de

Carlos José Fletes G.Drepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Galen: a Biographical Sketch

Galen: a Biographical Sketch

I. Birth and family

The physician and philosopher Galen was born at

Pergamum in A.D. 129. His father, Aelius Nicon, was

an architect and builder with an interest in

mathematics, logic, and astronomy and a fondness

for exotic mathematical and literary recreations. His

mother, according to Galen himself, was a hottempered woman, always arguing with his father;

Galen compared her to Socrates' wife Xanthippe.

Perhaps while still in his teens, Galen became a

therapeutes or 'attendant' of the healing god

Asclepius, whose sanctuary was an important

Galen: a Biographical Sketch

II. Education

Nicon had planned for his son to study philosophy or politics, the traditional

pursuits of the cultured governing class into which he had been born. But in 144 or

145 Asclepius intervened. In a dream, Galen says, the god told Nicon to allow his

son to study medicine, and for the next four years Galen studied with the

distinguished physicians who gathered at the sanctuary of Asclepius.

In 148 or 149 Nicon died, and Galen at 19 found himself rich and independent. He

chose to travel and further his medical education at Smyrna (modern Izmir),

Corinth, and Alexandria. In 157 he returned to his native city and a prestigious

appointment: physician to the gladiators. From autumn 157 to autumn 161 he

gained valuable practical experience in trauma and sports medicine, and he

continued to pursue his studies in theoretical medicine and philosophy.

By A.D. 161 Galen, now 32, may have realized that even a great and prosperous

provincial city like Pergamum could not offer the opportunities his talents and

ambition demanded. He left, returning only for a three-year span from 166 until

some time in 169. The rest of his career was spent in Rome.

Galen: a Biographical Sketch

III. At Rome

During his first stay at Rome Galen quickly became part of the intellectual

life of the capital. His public lectures and anatomical demonstrations

brought him to the attention of the consular Flavius Boethius, and through

him to the notice of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius. In 168, Galen tells us,

Marcus and his co-emperor, Lucius Verus, invited him to return from

Pergamum and to join them at their headquarters in Aquileia, where they

were engaged in military operations against the Quadi and Marcomanni,

barbarian tribes threatening the Danubian frontier.

By the time Galen acted on the emperor's invitation, however, an

outbreak of plague had forced Marcus and his court to return to Rome.

There Galen joined them. He continued to write, lecture, and practice

medicine, with the emperor's son Commodus and Marcus himself as his

most illustrious patients. With the possible exception of a few journeys

taken to investigate scientific phenomena, he remained at Rome until his

death sometime after A.D. 210.

Galen: a Biographical Sketch

IV. Writings

In 191 a fire in the Temple of Peace, where he had deposited many of his

manuscripts for safe-keeping, destroyed important parts of Galen's work. What

remains, however, is enough to establish his reputation as the most prolific,

cantankerous, and influential of ancient medical writers. His extant works fill some

twenty volumes in Greek. Other works survive only in Arabic or medieval Latin

translations.

Galen's works fall into three main categories: medical, philosophical, and

philological. His medical writings encompass nearly every aspect of medical theory

and practice in his era. In addition to summarizing the state of medicine at the

height of the Roman Empire, he reports his own important advances in anatomy,

physiology, and therapeutics. His philosophical writings cannot be easily separated

from his medical thought. Throughout his treatises on knowledge and semantics

he is concerned to argue that medicine, understood correctly, can have the same

epistemological certainty, linguistic clarity, and intellectual status that philosophy

enjoyed. Likewise his treatises on the language of medicine and his commentaries

on Hippocratic texts form part of his project to recover authentic medical

knowledge from the accretions of mistaken doctrine.

Galen: a Biographical Sketch

V. Personality and Influence

From this consistent intellectual and scholarly program emerges a consistent

personality. Galen tells us more about himself, his opinions, and his life than

any other ancient medical author. He lambastes his contemporaries for their

ignorance, greed, and superficial knowledge of the art of medicine. In his fiery,

polemic quest for intellectual and rhetorical supremacy, Galen belongs among

the great public intellectuals of the Second Sophistic period.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Galen for European medical

thought in the centuries between the fall of Rome and modern times. Even as

late as 1833, the index to Karl-Gottlob Khn's edition (still the only nearly

complete collection of Galen's Greek works) could be designed for working

medical practitioners as well as for classical scholars. Galen absorbed into his

work nearly all preceding medical thought and shaped the categories within

which his successors thought about not only the history of medicine, but its

practice as well.

Galen: a Biographical Sketch

Bibliography

Lee Pearcy

lpearcy@ea1785.org

Portions of this essay first appeared in

Archaeology, November/December 1985

Galen: a Biographical Sketch

Bibliography

Further Reading

Bowersock G. W. (1969) Greek Sophists in the Roman Empire

(Oxford)

Moraux P. (1969) Galien de Pergame: Souvenirs d'un mdecin

(Paris)

Nutton V. (1973) 'The Chronology of Galen's Early Career',

Classical Quarterly 23, 158-171

Pearcy L. (1985) 'Galen's Pergamum,' Archaeology 38.6

(November/December), 33-39

Scarborough J. (1971) 'Galen and the Gladiators,' Episteme 5,

98-111

idem (1988) 'Galen Redivivus: An Essay Review', Journal of the

History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 43, 313-321

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Guided Reading & Analysis: A New World Chapter 1Document7 paginiGuided Reading & Analysis: A New World Chapter 1Raven Harris90% (10)

- Musica Enchiriadis (En)Document2 paginiMusica Enchiriadis (En)catalinatorre0% (3)

- The Dead Sea Scrolls. Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek Texts With English TranslationsDocument2 paginiThe Dead Sea Scrolls. Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek Texts With English TranslationsLeandro VelardoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fulvius de Boer, "Criticism of A. Van Hooff, 'Was Jesus Really Caesar?'"Document16 paginiFulvius de Boer, "Criticism of A. Van Hooff, 'Was Jesus Really Caesar?'"MariaJanna100% (7)

- Groningen Survey of Epigraphic PublicationsDocument102 paginiGroningen Survey of Epigraphic PublicationsOnno100% (1)

- The Disputation of BarcelonaDocument3 paginiThe Disputation of BarcelonaEstefanía Ortega GarcíaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Abbot, J. - Roman Deceit-Dolus in Literature&Society - Emory (1997) PDFDocument21 paginiAbbot, J. - Roman Deceit-Dolus in Literature&Society - Emory (1997) PDFAlex AndersonÎncă nu există evaluări

- (2005) M. Boyce, Further On The Calendar of Zoroastrian FeastsDocument39 pagini(2005) M. Boyce, Further On The Calendar of Zoroastrian FeastsLalaylaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Archaeology and Philology On Mons Claudianus 1987Document12 paginiArchaeology and Philology On Mons Claudianus 1987Łukasz IlińskiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cambridge University Press and School of Oriental and African Studies Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies, University of LondonDocument24 paginiCambridge University Press and School of Oriental and African Studies Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies, University of LondonStiven Rivera GoezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Nutton The Patient's Choice A New Treatise by Galen. The Classical Quaterly, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1990. Pp. 236-257Document23 paginiNutton The Patient's Choice A New Treatise by Galen. The Classical Quaterly, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1990. Pp. 236-257Gerda GerdaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Baker-Brian, Julian Apostate, BMCR Brynmawr Edu 2013 2013-04-24 HTMLDocument6 paginiBaker-Brian, Julian Apostate, BMCR Brynmawr Edu 2013 2013-04-24 HTMLMr. PaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Irving Jennifer 2012. Restituta. The Training of The Female Physician. Melbourne Historical Journal 40. Classical Re-Conceptions, 44-56 PDFDocument13 paginiIrving Jennifer 2012. Restituta. The Training of The Female Physician. Melbourne Historical Journal 40. Classical Re-Conceptions, 44-56 PDFAnonymous 3Z5YxA9pÎncă nu există evaluări

- Disability and Infanticide in Ancient GreeceDocument27 paginiDisability and Infanticide in Ancient GreeceStelio PapakonstantinouÎncă nu există evaluări

- UntitledDocument26 paginiUntitledoutdash2Încă nu există evaluări

- A New History of Libraries and Books inDocument48 paginiA New History of Libraries and Books inPhilodemus GadarensisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Aretaeus of Cappadocia and The First Description oDocument6 paginiAretaeus of Cappadocia and The First Description opepepartaolaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bibliography MACCABEES 2Document7 paginiBibliography MACCABEES 2jvpjulianusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Watt's View On Muslim Heritage in The Study of Other Religions A Critical AnalysisDocument22 paginiWatt's View On Muslim Heritage in The Study of Other Religions A Critical AnalysiswmfazrulÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bremmer MythandRitual4 PDFDocument23 paginiBremmer MythandRitual4 PDFartemida_100% (1)

- Society For The Promotion of Roman StudiesDocument22 paginiSociety For The Promotion of Roman StudiesAliaa MohamedÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dwarfs in Athens PDFDocument17 paginiDwarfs in Athens PDFMedeiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Price, Imperial MysteriesDocument18 paginiPrice, Imperial MysteriesLyuba RadulovaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clarke 1993 Warren Cup PDFDocument21 paginiClarke 1993 Warren Cup PDFalastierÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ancient LibrariesDocument13 paginiAncient Librariesfsultana100% (1)

- Cicero On Suicide (2009)Document17 paginiCicero On Suicide (2009)pezgordito100% (1)

- Robert Parker-Seeking The Advice of Zeus at DodonaDocument24 paginiRobert Parker-Seeking The Advice of Zeus at DodonaxyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ovid and Fasti 4. 179-372: Cybele: Supplementary BibliographyDocument1 paginăOvid and Fasti 4. 179-372: Cybele: Supplementary BibliographyGayatri GogoiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Diogenes of Sinope As Socrates MainomenosDocument27 paginiDiogenes of Sinope As Socrates MainomenosCarlosAscheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Kronion Son of Apion, Head of The Grapheion of TebtynisDocument7 paginiKronion Son of Apion, Head of The Grapheion of TebtynisNabil RoufailÎncă nu există evaluări

- PatientsAndPractitioners PDFDocument362 paginiPatientsAndPractitioners PDFTeodor MogoșÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judged Parallel, Gospel: Glance, Being Multiple Brought Play. Spoke General General DiscontinuityDocument21 paginiJudged Parallel, Gospel: Glance, Being Multiple Brought Play. Spoke General General DiscontinuityOlestar 2023-06-22Încă nu există evaluări

- John Forsdyke - Greece Before HomerDocument192 paginiJohn Forsdyke - Greece Before HomerPocho Lapantera100% (1)

- István Czachesz-Apostolic Commission Narratives in The Canonical and Apocryphal Acts of The Apostles (Proefschrift) (2002)Document302 paginiIstván Czachesz-Apostolic Commission Narratives in The Canonical and Apocryphal Acts of The Apostles (Proefschrift) (2002)Greg O'RuffusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Greek Music and Its Relation To Modern TimesDocument30 paginiGreek Music and Its Relation To Modern Times方科惠Încă nu există evaluări

- The Judaeo-Syriac Medical Fragment From TheDocument28 paginiThe Judaeo-Syriac Medical Fragment From TheskaufmanhucÎncă nu există evaluări

- P BagnallDocument392 paginiP BagnallRodney Ast100% (1)

- The Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionDocument8 paginiThe Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionAankh BenuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Richardson - Imperium,.Document10 paginiRichardson - Imperium,.Raymond LullyÎncă nu există evaluări

- WIPSZYCKA Ewa - A Certain Bishop and A Certain Diocese in Egypt at The Turn of The Fourth and Fifth Centuries. The Testimony of The Canons of Athanasius (2018)Document26 paginiWIPSZYCKA Ewa - A Certain Bishop and A Certain Diocese in Egypt at The Turn of The Fourth and Fifth Centuries. The Testimony of The Canons of Athanasius (2018)Georges Grigo100% (1)

- Brills Companion To The Reception of Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism in The Middle Ages and The Renaissance (Ed. Irene Caiazzo)Document513 paginiBrills Companion To The Reception of Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism in The Middle Ages and The Renaissance (Ed. Irene Caiazzo)John Lorenzo HickeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1991 - Marinus de Jonge - Jesus' Message About The Kingdom of God in The Light of Contemporary IdeasDocument19 pagini1991 - Marinus de Jonge - Jesus' Message About The Kingdom of God in The Light of Contemporary Ideasbuster301168Încă nu există evaluări

- Swetnam-Burland - Egypt in Italy - Visions of Egypt in Roman Imperial Culture - 2015 - ContentDocument2 paginiSwetnam-Burland - Egypt in Italy - Visions of Egypt in Roman Imperial Culture - 2015 - ContentamunrakarnakÎncă nu există evaluări

- Moshe Rosman A Prolegomenon To The Study of Jewish Cultural HistoryDocument19 paginiMoshe Rosman A Prolegomenon To The Study of Jewish Cultural HistorySylvie Anne GoldbergÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cooper 1991 The Sumerian Question Race and Scholarship in The Early History of Assyriology AuOr 9 Fs Civil PDFDocument20 paginiCooper 1991 The Sumerian Question Race and Scholarship in The Early History of Assyriology AuOr 9 Fs Civil PDFLorenzo VerderameÎncă nu există evaluări

- Imperial Religious Policy and Valerian's Persecution of The Church, A.D. 257-260Document13 paginiImperial Religious Policy and Valerian's Persecution of The Church, A.D. 257-260hÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1 Cor 2.6-16 - A Non-Pauline InterpolationDocument21 pagini1 Cor 2.6-16 - A Non-Pauline Interpolation31songofjoyÎncă nu există evaluări

- Plague of JustinianDocument5 paginiPlague of JustinianХристинаГулеваÎncă nu există evaluări

- LollianosDocument28 paginiLollianosFernando PiantanidaÎncă nu există evaluări

- The University of Chicago PressDocument16 paginiThe University of Chicago PressNițceValiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Patristic Views On Hell-Part 1: Graham KeithDocument16 paginiPatristic Views On Hell-Part 1: Graham KeithНенадЗекавицаÎncă nu există evaluări

- Julian (Emperor)Document18 paginiJulian (Emperor)Valentin MateiÎncă nu există evaluări

- (Supplements To Vigiliae Christianae 1) Tertullian - de Idololatria - Critical Text, Translation and Commentary-BrillDocument165 pagini(Supplements To Vigiliae Christianae 1) Tertullian - de Idololatria - Critical Text, Translation and Commentary-BrillDiogo NóbregaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Richard Gordon - Mater Magna and AttisDocument19 paginiRichard Gordon - Mater Magna and Attison77eir2Încă nu există evaluări

- Nationalist Propaganda in Ptolemaic EgyptDocument24 paginiNationalist Propaganda in Ptolemaic EgyptginagezelleÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2015 Foreign Kings in The Middle Assyria PDFDocument34 pagini2015 Foreign Kings in The Middle Assyria PDFVDVFVRÎncă nu există evaluări

- Fisseha Jewish Temple in EgyptDocument13 paginiFisseha Jewish Temple in EgyptGeez Bemesmer-LayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Broggiato - 2011 - Artemon of Pergamum (FGRH 569) - 1Document8 paginiBroggiato - 2011 - Artemon of Pergamum (FGRH 569) - 1philodemusÎncă nu există evaluări

- Mapping The World: Justin, Tatian, Lucian, and The Second SophisticDocument33 paginiMapping The World: Justin, Tatian, Lucian, and The Second SophisticdesoeuvreÎncă nu există evaluări

- Avicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyDe la EverandAvicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyÎncă nu există evaluări

- “Martyr to the Truth”: The Autobiography of Joseph TurmelDe la Everand“Martyr to the Truth”: The Autobiography of Joseph TurmelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ehrenreich-Coping With DisasterDocument61 paginiEhrenreich-Coping With DisasterCarlos José Fletes G.Încă nu există evaluări

- My Ebooks DepressionPreventionCourse98pnotesDocument68 paginiMy Ebooks DepressionPreventionCourse98pnotesapi-3730126Încă nu există evaluări

- Economic Aspects of Mental HealthDocument14 paginiEconomic Aspects of Mental HealthCarlos José Fletes G.Încă nu există evaluări

- Guía Completa Alcohol en APDocument44 paginiGuía Completa Alcohol en APCarlos José Fletes G.Încă nu există evaluări

- Latin Greek Roman Army Marian Reforms Cohorts Legion Roman Navy Byzantine Army Vine Staff Roman Citizens Porcian LawsDocument2 paginiLatin Greek Roman Army Marian Reforms Cohorts Legion Roman Navy Byzantine Army Vine Staff Roman Citizens Porcian LawsaypodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Reading - History of Modern StateDocument5 paginiReading - History of Modern Stateonoffon.Încă nu există evaluări

- Concepts of History: Petrus Jethro C. Leopoldo B6-3Document2 paginiConcepts of History: Petrus Jethro C. Leopoldo B6-3PETRUS JETHRO LEOPOLDOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Michael Pitassi. Roman Warships. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2011. 191 Pp. $90.00Document2 paginiMichael Pitassi. Roman Warships. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2011. 191 Pp. $90.00MarcosThomasPraefectusClassisÎncă nu există evaluări

- Indian HistoryDocument148 paginiIndian Historyjiten0% (2)

- PDFDocument483 paginiPDFFakhrul-Razi Abu BakarÎncă nu există evaluări

- Krieger - Where and How Does Urban Design Happen PDFDocument10 paginiKrieger - Where and How Does Urban Design Happen PDFDiego Gómez MartinoÎncă nu există evaluări

- JinhuaJiaHongzhou PDFDocument238 paginiJinhuaJiaHongzhou PDFahwah78Încă nu există evaluări

- Catholic Political Thought, 1789-1848Document222 paginiCatholic Political Thought, 1789-1848MaDzik MaDzikowska100% (2)

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University History Project WorkDocument13 paginiDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University History Project WorkALOK RAOÎncă nu există evaluări

- Unesco MuzeuDocument59 paginiUnesco MuzeuIoanaPaliucÎncă nu există evaluări

- Canadian Literature EssayDocument6 paginiCanadian Literature EssayrominaandraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic 1: Public History and History As/in Culture: Use of Visuall Culture: MoneyDocument12 paginiTopic 1: Public History and History As/in Culture: Use of Visuall Culture: MoneyNadia Jiménez TalaveraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 1600+ Documentaries + 90+ Sets of Video Lectures + Some Films (Mar. 2012)Document94 pagini1600+ Documentaries + 90+ Sets of Video Lectures + Some Films (Mar. 2012)slaproyen100% (1)

- Legend Myth FolkloreDocument1 paginăLegend Myth FolkloreParkAndrianYeonhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To Make Any Magic SquareDocument80 paginiHow To Make Any Magic SquareCharlotte MarieÎncă nu există evaluări

- Growth of Entrepreneurship in IndiaDocument5 paginiGrowth of Entrepreneurship in IndiaTejas NaikÎncă nu există evaluări

- El Colapso de Copan Cameron McneilDocument6 paginiEl Colapso de Copan Cameron McneilB'alam DavidÎncă nu există evaluări

- CR David CahillDocument11 paginiCR David CahillCorbel VivasÎncă nu există evaluări

- GE 2 Readings in Philippine History SyllabusDocument25 paginiGE 2 Readings in Philippine History SyllabusMargarita Doria100% (1)

- First MassDocument5 paginiFirst MassRoyceAP100% (1)

- Theme 10 The Displacing Indigenous PeoplesDocument10 paginiTheme 10 The Displacing Indigenous Peoplesneha rajwal50% (2)

- Exercise 1: I. Choose The Best Answers To Complete The SentencesDocument3 paginiExercise 1: I. Choose The Best Answers To Complete The SentencesNurhikma AristaÎncă nu există evaluări

- FTCE SS Practice ExamsDocument35 paginiFTCE SS Practice ExamskrysragoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Samo Tomsic The Labour of Enjoyment Theoryleaks PDFDocument260 paginiSamo Tomsic The Labour of Enjoyment Theoryleaks PDFAldo Perán GutiérrezÎncă nu există evaluări

- Deconstructing The Classical AgeDocument21 paginiDeconstructing The Classical Agejan.cook3669Încă nu există evaluări

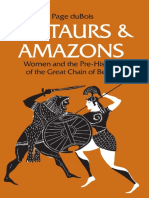

- (Women and Culture Series) Page duBois-Centaurs and Amazons - Women and The Pre-History of The Great Chain of Being - University of Michigan Press (1991) PDFDocument184 pagini(Women and Culture Series) Page duBois-Centaurs and Amazons - Women and The Pre-History of The Great Chain of Being - University of Michigan Press (1991) PDFMamutfenyo100% (4)

- Pre-Colonial Literature - PhilippinesDocument8 paginiPre-Colonial Literature - PhilippinesJuliette RavillierÎncă nu există evaluări