Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Choice of Place of Arbitration: Compiled By-Asst. Prof. Anjali Bhatt

Încărcat de

deepak singhal0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

144 vizualizări36 paginiTitlu original

Place of Arbitration

Drepturi de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

PPTX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PPTX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

0 evaluări0% au considerat acest document util (0 voturi)

144 vizualizări36 paginiChoice of Place of Arbitration: Compiled By-Asst. Prof. Anjali Bhatt

Încărcat de

deepak singhalDrepturi de autor:

© All Rights Reserved

Formate disponibile

Descărcați ca PPTX, PDF, TXT sau citiți online pe Scribd

Sunteți pe pagina 1din 36

CHOICE OF PLACE OF ARBITRATION

Compiled by- Asst. Prof. Anjali Bhatt

Contract law

• It is a well-settled position of law in India (ABC Laminart (P) Ltd. v. A.P. Agencies,

(1989) 2 SCC 163) that parties by contract cannot oust the jurisdiction of courts

absolutely, as such clauses are contrary to public policy and are void.

• However, referring disputes to an Arbitral Tribunal for adjudication instead of

courts is not barred. Such reference is permitted as it does not entirely oust the

jurisdiction of courts.

• NTPC v. Singer Co., (1992) 3 SCC 551- freedom of parties to choose- law that is

applicable to the contract, the law applicable to the arbitration agreement (lex

arbitri), and the procedural law governing the arbitration (curial law).

• Naviera Amazonica Peruana SA v. Compania International de Seguros del Peru

(1988)

• The aforesaid laws are discussed hereinafter.

• Applicable law — Contract

• The term “applicable law” or “proper law of the contract” is the law that governs

the discharge of the contract itself. In case of disputes arising, the Arbitral

Tribunal applies the applicable law to determine the substantive dispute.

Applicable law or the proper law of the contract are terms which refer to a legal

system in which a contract may be executed.

• Applicable law — Arbitration agreement

• The law applicable to the arbitration clause can be classified in two categories,

namely, the juridical seat (lex arbitri), and the curial law.

• Juridical seat or lex arbitri

• The lex arbitri would determine the courts which can exercise supervisory

jurisdiction over the arbitration proceedings.

• “Lex arbitri” may be best explained by referring to the judgment in XL Insurance

Ltd. v. Owens Corning (2000).

• The English Court held that the choice of law (proper law) being different from

the lex arbitri would not invalidate the arbitration clause.

• Since the parties have chosen to seek refuge under the English Law for

arbitration, the provisions of the English Arbitration Act would be applicable and

English Law shall solely govern the matters falling within the scope of the

arbitration agreement/clause, including formal validity of arbitration agreement

and the jurisdiction of the arbitrators.

• Curial law

• The procedural law applicable to the conduct of arbitration is known as the curial

law.

• A conflict between two jurisdictions would necessarily arise only in international

commercial arbitrations. The term “international commercial arbitration” is defined under

Section 2(1)(f) of the 1996 Act and is self explanatory.

• The provisions relevant for understanding conspectus of seat and venue under the 1996

Act are Sections 2(2) and 20. Section 2(2) in an ominously cryptic manner reads as follows:

Section 2(2)- This Part shall apply where place of arbitration is in India.

• On a bare perusal of the said section, it seems that the 1996 Act was applicable only to

arbitrations which were taking place in India.

Section 20. Place of arbitration.—(1) The parties are free to agree on the place of

arbitration.

• (2) Failing any agreement referred to in sub-section (1), the place of arbitration shall be

determined by the Arbitral Tribunal having regard to the circumstances of the case,

including the convenience of the parties.

• (3) Notwithstanding sub-section (1) or sub-section (2), the Arbitral Tribunal may, unless

otherwise agreed by the parties, meet at any place it considers appropriate for

consultation among its members, for hearing witnesses, experts or the parties, or for

inspection of documents, goods or other property.

Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading SA (2002)4 SCC

105

• Briefly stating facts, the parties had entered into a contract wherein the arbitration clause

provided that the arbitration was to be as per rules of International Chamber of Commerce

(ICC). Disputes having arisen between the parties, the respondent initiated the arbitration

proceedings at ICC.

• In addition to such initiation, the respondent also filed an application under Section 9 of the

1996 Act seeking an injunction against the appellants restraining them from alienating in any

manner their business assets and properties.

• The District and High Court both held that the courts in India have jurisdiction to adjudicate the

application despite the “place of arbitration” being outside India.

• These orders were challenged before the Supreme Court.

• The simple contention raised by the appellant before the Supreme Court based on a plain

reading of Section 2(2) was that, unless the international commercial arbitration is taking place

in India, Part I will not apply.

• According to the interpretation cast by the Supreme Court, an international commercial

arbitration where an Indian party is involved, being proceeded with in any part of the world,

would confer jurisdiction on Indian courts to exercise powers under Part 1 of the 1996 Act.

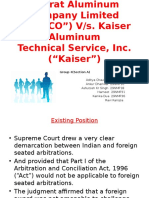

Bharat Aluminium Company v. Kaiser Aluminium

Technical Services Inc. (2012)9 SCC 552

• The Supreme Court interpreted the word “place” to mean “seat” or “venue”

depending on the section in which the word was used. The Court while dealing

with Sections 2(2) and 20, extensively laid out the concept of seat and venue.

• Court observed that the section has to be interpreted to mean that only when

the seat/place of arbitration is in India, will Part I apply, restoring the distinction

between seat and venue.

• Further consolidating the doctrine of seat and venue under the 1996 Act, the

court clarified that the term “place” used in Sections 20(1) and (2) would connote

“seat” and the term “place” used in Section 20(3) would connote “venue”.

Enercon (India) Ltd. v. Enercon GmbH (2014)5 SCC 1

• Enercon Case clarified the position of law in case the parties have failed to or

improperly mentioned the law applicable to the arbitration agreement.

• The court, placing reliance on the judgment in Naviera Amazonica

(1988) adopted the “closest and most intimate connection test”.

Report 246 — Law Commission of

India

• The Report discussed in great detail the need to amend Sections 2(2) and 20. The

changes suggested replacing the word “place” with the words “seat” and

“venue”, in accordance with the explanation provided by BALCO.

• The amendment further proposed addition of a proviso to Section 2(2) permitting

parties to choose to remain under the supervisory jurisdiction of Indian courts.

• The Report further suggested replacing the word “place” in Section 20(1) with the

words “seat” and “venue”, replacing the word place with “seat” in Section 20(2)

and with “venue” in Section 20(3).

2015 Amendment

• The Amendment Act has, however, incorporated the proviso to Section 2(2) suggested by

the amendment.

• The legal quandary between a “seat” and “venue” of arbitration was resolved by

India’s Supreme Court (“SC”) in its judgment in Bharat Aluminium

Company v. Kaiser Aluminium Technical Services (“BALCO”).

• This distinction has unfortunately, however, been garbled by a recent SC decision

in Brahmani River Pellets v. Kamachi Industries (CIVIL APPEAL NO. 5850

2019) (“Brahmani”). In Brahmani, the SC has taken the view that the venue of the

arbitration can be assumed to be the seat, until explicitly stated otherwise.

• The SC’s judgment in Brahmani

• The sales contract had the following arbitration clause:

• “Clause 18. (…) the venue of Arbitration shall be Bhubaneswar.”

• After the dispute arose, the respondent filed a petition before the Madras High Court seeking the appointment of

an arbitrator. The claimant contested this petition on the premise that the parties in Clause 18 of the Contract

have agreed that the seat of arbitration would be Bhubaneswar and therefore, only the Orissa High Court situated

there would have exclusive jurisdiction to appoint the arbitrator.

• The Madras High Court considered the challenge and held that in the absence of any clause excluding the

jurisdiction of other courts, it would continue to exercise supervisory jurisdiction along with the Orissa High Court.

• Aggrieved by this, an appeal was made before the SC. The appellant contended that when parties to an agreement

mention a venue, it results in the selection of a seat for the arbitration proceedings. In its arguments before the

SC, the appellant relied on Indus Mobile Distribution Private Limited v. Datawind Innovations Private Limited &Ors.

(“Indus”), wherein the SC had determined that once a seat had been fixed it had exclusive jurisdiction, to the

exclusion of other courts where the cause of action arose. In view of this, the appellant submitted that the Madras

High Court erred by exercising jurisdiction as the same was under the domain of the Orissa High Court only. On the

other hand, the respondent argued that merely mentioning the venue does not give it the status of the juridical

seat having exclusive jurisdiction. In the absence of the selection of a seat, the courts at the place of cause of

action should have jurisdiction. Since the cause of action arose at both the places i.e., Bhubaneswar and Chennai,

courts in both places were competent to deal with the matter.

• The SC held that, “considering the agreement of the parties having Bhubaneswar as the venue of arbitration, the

intention of the parties is to exclude all other courts.”

• Recently, in the case of L&T Finance Ltd. v. Manoj Pathak & Ors. (Com. Arb.

Petition No. 1315 of 2019.) , the Delhi High Court identified the tests applicable to

identify a seat of arbitration:

• “29. There emerges the following trifecta of propositions in regard to a domestic

arbitration:

• a. A stated venue is the seat of the arbitration unless there are clear indicators

that the place named is a mere venue, a meeting place of convenience, and not

the seat;

• b. Where there is an unqualified nomination of a seat (i.e. without specifying the

place as a mere venue), it is courts where that seat is situated that would have

exclusive jurisdiction; and

• c. It is only where no venue/seat is named (or where it is clear that the named

place is merely a place of convenience for meetings) that any other consideration

of jurisdiction may arise, such as cause of action.”

THE END

INDUS MOBILE DISTRIBUTION PVT. LTD. V

DATAWIND INNOVATIONS PVT. LTD. & ORS

(DECIDED ON APRIL 19, 2017)

• Recently, a Division Bench of the Supreme Court in Indus Mobile Distribution Pvt.

Ltd. v Datawind Innovations Pvt. Ltd. & Ors (Civil Appeal Nos. 5370-5371 of 2017,

decided on April 19, 2017) has answered in the affirmative the question

“whether, when the seat of arbitration is Mumbai, an exclusive jurisdiction clause

stating that the courts at Mumbai alone would have jurisdiction in respect of

disputes arising under the agreement would oust all other courts”.

Factual Background

• Datawind Innovations Pvt. Ltd. (“Datawind”), having its registered office in

Amritsar, Punjab, is engaged in the manufacturing, marketing and distribution of

mobile phones, tablets and their accessories. Datawind was engaged in the

supply of goods from New Delhi to Indus Mobile Distribution Pvt. Ltd. (“Indus”)

based in Chennai and subsequently, upon Indus’ desire to act as a retail chain

partner for Datawind, the parties entered into an agreement in 2014 towards this

end (“Agreement”). Clauses 18 and 19 of the Agreement contained the dispute

resolution and jurisdiction clauses.

• “Dispute Resolution Mechanism:

Arbitration: In case of any dispute or differences arising between parties out of or in relation to the

construction, meaning, scope, operation or effect of this Agreement or breach of this Agreement, parties

shall make efforts in good faith to amicably resolve such dispute.

If such dispute or difference cannot be amicably resolved by the parties (Dispute) within thirty days of its

occurrence, or such longer time as mutually agreed, either party may refer the dispute to the designated

senior officers of the parties.

If the Dispute cannot be amicably resolved by such officers within thirty (30) days from the date of referral,

or within such longer time as mutually agreed, such Dispute shall be finally settled by arbitration conducted

under the provisions of the Arbitration & Conciliation Act 1996 by reference to a sole Arbitrator which shall

be mutually agreed by the parties. Such arbitration shall be conducted at Mumbai, in English language.

The arbitration award shall be final and the judgment thereupon may be entered in any court having

jurisdiction over the parties hereto or application may be made to such court for a judicial acceptance of the

award and an order of enforcement, as the case may be. The Arbitrator shall have the power to order

specific performance of the Agreement. Each Party shall bear its own costs of the Arbitration.

It is hereby agreed between the Parties that they will continue to perform their respective obligations under

this Agreement during the pendency of the Dispute.”

Delhi High Court Decision

• Clause 19. All disputes & differences of any kind whatever arising out of or in

connection with this Agreement shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of

courts of Mumbai only.” (Emphasis supplied).

• A dispute arose between the parties and a notice was served by Datawind on

Indus in September, 2015, wherein it was stated that Indus was in default of

payment of outstanding dues amounting to Rs. 5 crores with interest thereon.

Datawind also invoked arbitration under Clause 18 of the Agreement and

appointed a sole arbitrator. Indus, vide its reply, objected to the appointment of

the sole arbitrator and further, denied the contents of Datawind’s notice.

• Subsequently, Datawind filed two petitions before the Delhi High Court – one

under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, as amended (the

“Arbitration Act”) praying for certain interim reliefs in the matter and another

under Section 11 of the Arbitration Act for the appointment of an arbitrator.

• The Delhi High Court disposed of the two petitions by a common judgment

(which was challenged by Indus before the Supreme Court) holding, inter alia,

that since no part of the cause of action arose in Mumbai, the courts of only

three territories viz., Delhi and Chennai (being the places of origin and supply of

goods, respectively), and Amritsar (where the registered office of Datawind is

situated) could have jurisdiction in the matter. Therefore, the Delhi High Court

concluded that the exclusive jurisdiction clause (viz. Clause 19 of the Agreement)

would not apply on facts, as the courts in Mumbai would have no jurisdiction at

all and the Delhi High Court, being the first court that was approached, would

have jurisdiction. Accordingly, the Delhi High Court passed interim orders as well

as appointed a sole arbitrator.

Decision of the Supreme Court

• The Supreme Court, in its judgment (“Judgment”), has dealt with the concept of

“seat” of arbitration in considerable detail and for the purpose, it has referred to its

earlier judgments dealing with the principles of “juridical seat” and “place” of

arbitration, notably

a) Bharat Aluminium Co. v Kaiser Aluminium Technical Services Ltd. (2012) 9 SCC 552 ,

b) Enercon (India) Ltd. v Enercon Gmbh (2014) 5 SCC 1,

c) Reliance Industries Ltd. v Union of India (2014) 7 SCC 603,

d) Union of India v Reliance Industries Limited and Others (2015) 10 SCC 213 and

e) Eitzen Bulk A/S v Ashapura Minechem Limited and Another (2016) 11 SCC 508.

• The Judgment also discussed the relevant provisions of the Arbitration Act, including

Section 20 which, inter alia, provides autonomy to the parties to an arbitration

agreement to agree on the place of arbitration.

• The following important principles emerge from the Judgment pursuant to discussion

of the above mentioned judgments and the relevant provisions of the Arbitration Act:

• It is an internationally accepted principle that arbitrations are anchored to the

seat/place/ situs of arbitration and therefore, the ‘seat’ of arbitration is intended

to be its centre of gravity. However, choosing a ‘seat’ of arbitration does not

mean that all proceedings of the arbitration are to be held at the seat of

arbitration. The arbitrators are at liberty to hold meetings at a place which is of

convenience to all concerned. (ENERCON CASE)

• Once the seat of arbitration has been fixed, it would be in the nature of an exclusive

jurisdiction clause as to the courts which exercise supervisory powers over the

arbitration.

• ‘Juridical seat’ is nothing but the ‘legal place’ of arbitration. Once the parties have

decided a particular place as the juridical seat or legal place of arbitration (a city in

India or a foreign country), then the courts of that place alone would have jurisdiction

over the arbitration. Therefore, in cases where the seat of arbitration is located outside

India, by necessary implication Part I of the Arbitration Act is excluded as the

supervisory jurisdiction of courts over the arbitration goes along with the “seat”.

(RELIANCE )

• The mere choosing of the juridical seat of arbitration attracts the law applicable to

such location. In other words, it would not be necessary to specify which law would

apply to the arbitration proceedings, since the law of the particular country would

apply ipso jure. Accordingly, parties may well choose a particular place of arbitration

precisely because its lex arbitri is one which they find attractive. Nevertheless, once a

place of arbitration has been chosen, it brings with it its own law. If that law contains

provisions that are mandatory so far as arbitration is concerned, those provisions must

be obeyed. (EITZEN)

Interpretation by the Supreme Court as

under:

• “Under the Law of Arbitration, unlike the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 which applies

to suits filed in courts, a reference to “seat” is a concept by which a neutral venue can

be chosen by the parties to an arbitration clause. The neutral venue may not in the

classical sense have jurisdiction – that is, no part of the cause of action may have

arisen at the neutral venue and neither would any of the provisions of Section 16 to

21 of the CPC be attracted. In arbitration law however, as has been held above, the

moment “seat” is determined, the fact that the seat is at Mumbai would vest

Mumbai courts with exclusive jurisdiction for purposes of regulating arbitral

proceedings arising out of the agreement between the parties.”

• Thus, the Supreme Court arrived at the conclusion that the courts of the place where

the seat of arbitration is located would have exclusive jurisdiction for the purpose of

regulating arbitration proceedings between the parties. Accordingly, it was held that

under the Agreement, the courts at Mumbai alone have jurisdiction to the exclusion

of all other courts in the country, as the juridical seat of arbitration is at Mumbai.

Comments on the Judgment:

• Although in the instant case, there was a jurisdiction clause conferring jurisdiction on the courts

of Mumbai, the judgment goes a step further to reiterate the principle that once “seat” is

determined, the courts of that place will have exclusive jurisdiction for purposes of regulating

arbitral proceedings arising out of the agreement between the parties.

• It must be noted that the judgment deals with situations where parties have to approach courts

prior to commencement of or during the pendency of arbitration proceedings. The enforcement

of arbitral awards will have to be in the jurisdiciton where the award-debtor is situated and will

have to be in accordance with applicable laws for enforcement of arbitral awards.

• The Judgment is a welcome step towards making India an arbitration-friendly jurisdiction and

another example where courts are interpreting provisions in a way that upholds party autonomy

and prevents parties from reneging on agreements relating to conduct of arbitral proceedings.

• By holding that the courts located at the seat of arbitration will have exclusive jurisdiction to

deal with matters relating to the conduct of arbitral proceedings (including filing of petitions for

appointment of arbitrators and seeking interim reliefs as is the case in the present Judgment)

will help in preventing parties from approaching courts as per their convenience as well as avoid

multiplicity of proceedings being initiated by parties in different courts across the country

PARTIES HAVE NOT AGREED FOR SEAT LAW AND

THE TRIBUNAL FAILED TO DETERMINE IT

• The Supreme Court of India in Union of India v. Hardy Exploration and Production

(India) Inc. (2018) held that Indian courts will have jurisdiction to set aside the

arbitral award under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 in

case the parties have not agreed for seat law and the Tribunal failed to determine

it.

• The Court was faced with the question that when the arbitration agreement

specify the venue of arbitration but does not specify the seat, then on what basis

and by which principle, the parties have to decide the seat law.

• The disputed arbitration clause, in this case, provided Indian law as the governing

law and arbitration to be conducted as per the Uncitral (United Nations

Commission on International Trade Law) Model Law specifying the venue to be

Kuala Lumpur.

• The Court determined India to be the seat law while deciding that it has

jurisdiction for setting aside the arbitral award.

Court’s Authority to Select Arbitral Seat in Absence of

Parties’ Agreement

• Agreement on the choice of the law of the seat is essential as it clarifies that which court will

have supervisory jurisdiction over the arbitration proceedings.

• Principally, parties are required to reach an agreement with regard to the choice of the seat

law. In absence of such agreement, the Arbitral Tribunal has the power to decide the place of

arbitration as per Section 20(2) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

• Moreover, the Uncitral Model Law of 1985, on which the arbitration law of India is based

upon, also state that the Tribunal will determine the place of arbitration in case the parties fail

to do so.

• The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 does not grant the local courts the power to select

the arbitral seat. No such express power is granted under the Model Law. The arbitration

statutes across the globe either allow the Arbitral Tribunal or the arbitral institution to decide

the law of the seat in case there is no agreement between the parties regarding choice of the

seat law.

• However, in few legislations like Swedish Arbitration Act and Japanese Arbitration Law, the

local courts can select the arbitral seats in circumstances where the parties have neither

agreed upon a seat nor a means for selecting a seat.

• In India, Part I of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 only applies when the

seat of arbitration is India as stated in Section 2(2) of the Act. The Court while

deciding the application made under the provisions of Part I has to determine

whether the place of arbitration is in India or not. Therefore, in deciding such

application the courts decide the seat law in case the parties’ agreement is silent

on it.

Court’s Approach in Determination of

Law of the Seat

• The dispute regarding the choice of the seat law arises as the parties have been using the

term “place”, “venue” and “seat” interchangeably in their contracts. The Indian courts in

various cases have interpreted the agreement of the parties in order to determine the law

of the seat. In Enercon (India) Ltd. v. Enercon GmbH, (2014) 5 SCC 1 the question before

the Court was whether the phrase “venue shall be London” as used in the arbitration

agreement imply that London was the seat law. The Supreme Court in this case, while

recognising the test of the closest and most intimate connection held by expressly making

Indian law as the governing law of the arbitration agreement and the underlying contract,

the parties have designated India to be the seat of arbitration.

• The Court in Harmony Innovation Shipping Ltd. v. Gupta Coal India Ltd. (2015) 9 SCC 172

applied the test of presumed intention and held that London will be the seat law. The

Court came to such conclusion by stating that parties intended to make London as the

seat law and for this there is ample indication through various phrases used in the

arbitration clause like “arbitration in London to apply”, arbitrators are to be the members

of the “London Arbitration Association” and the contract “to be governed and construed

according to the English law”.

• The Supreme Court’s judgment in Roger Shashoua v. Mukesh Sharma

(2017) 14 SCC 722 (Roger Shashoua) sheds further light on the court’s approach

to interpreting arbitration agreements, particularly regarding the parties’ implied

choice of seat. The Court found that the designation of London as the “venue” of

the arbitration in the absence of any express designation of a seat would suggest

that the parties agreed that London would be the seat of the arbitration (in the

absence of anything to the contrary).

• The Supreme Court in Eitzen Bulk A/S v. Ashapura Minechem Ltd. (2016) 11 SCC

508 held that since the arbitration clause stipulates that the dispute shall be

settled in London and English law would apply to the arbitration, the intention of

the parties is manifestly clear to exclude the applicability of Part I of the 1996 Act

and thus, the conduct of the arbitration, as well as any objections relating thereto

including the award, shall be governed by English law.

• In other jurisdictions, courts have applied various approaches in order to

determine the seat law in case of parties’ failure to do so. In one case, a court

held that such an agreement could be inferred from the parties’ contractual

relationship. In another case, the court identified what it considered to be the

effective place of arbitration i.e. the place where all relevant actions in the

arbitration have taken place; another court held that, the place of the last oral

hearing should be deemed the place of arbitration.

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Konkan Railway Corporation Ltd. Vs Rani Construction Pvt. LTDDocument39 paginiKonkan Railway Corporation Ltd. Vs Rani Construction Pvt. LTDjuhi100% (1)

- Arbitration Case BriefsDocument39 paginiArbitration Case BriefsRithvik MathurÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court DecisionDocument9 paginiSupreme Court DecisionWSYX/WTTEÎncă nu există evaluări

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaDe la EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaEvaluare: 4.5 din 5 stele4.5/5 (4)

- Place of Arbitration and Seat of ArbitrationDocument11 paginiPlace of Arbitration and Seat of ArbitrationNiti KaushikÎncă nu există evaluări

- Format of The Bill of Exchange PDFDocument1 paginăFormat of The Bill of Exchange PDFdeepak singhal100% (1)

- Arbitration Viva PDFDocument39 paginiArbitration Viva PDFyalini tholgappianÎncă nu există evaluări

- Written Statement Vikas AggarwalDocument12 paginiWritten Statement Vikas Aggarwaldeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Persons and Family Relations Departmental Syllabus 31 July 2022Document19 paginiPersons and Family Relations Departmental Syllabus 31 July 2022Frances Rexanne AmbitaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2020 Moot Court and Internship GuidelinesDocument7 pagini2020 Moot Court and Internship Guidelinesdeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- People Vs SuelaDocument2 paginiPeople Vs SuelaCJ FaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 6 Vikas Sud ABDocument15 pagini6 Vikas Sud ABkrishanÎncă nu există evaluări

- BALCO Vs KaiserDocument13 paginiBALCO Vs KaiserHarneet Sachdeva0% (1)

- Article - Seat Vs VenueDocument8 paginiArticle - Seat Vs VenueShubham MadaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bharat Aluminium Co LTD V Kaiser Aluminium Technical IncDocument9 paginiBharat Aluminium Co LTD V Kaiser Aluminium Technical Incabhishek5641100% (1)

- De Jure Seat of ArbitrationDocument7 paginiDe Jure Seat of ArbitrationKanishk JoshiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration Case On JurisdictionDocument5 paginiArbitration Case On JurisdictionreecemistinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Topic 2 - Applicability of Part I, Section 2Document11 paginiTopic 2 - Applicability of Part I, Section 2ArchitUniyalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Justice Ramesh D Dhanuka Judge Bombay High Court 1680326277Document103 paginiJustice Ramesh D Dhanuka Judge Bombay High Court 1680326277sangeetha ramÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seat Vs VenueDocument7 paginiSeat Vs Venuekartik aryÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration Law India Critical AnalysisDocument23 paginiArbitration Law India Critical AnalysisKailash KhaliÎncă nu există evaluări

- Harshit PPDocument4 paginiHarshit PPVishu DhallÎncă nu există evaluări

- ITL Module 3Document27 paginiITL Module 3joy parimalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Q N A - ADRDocument37 paginiQ N A - ADRSrinivasa RaoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adr Presentatiion - PASL WIND SOLUTIONS PRIVATE LIMITED-1Document5 paginiAdr Presentatiion - PASL WIND SOLUTIONS PRIVATE LIMITED-1sanjayÎncă nu există evaluări

- Brief Notes On Cases of AdrDocument5 paginiBrief Notes On Cases of AdrTRILOK CHANDÎncă nu există evaluări

- 001 - 2006 - Arbitration Law-1 PDFDocument27 pagini001 - 2006 - Arbitration Law-1 PDFkrishnakumariramÎncă nu există evaluări

- Balco Case NlsiuDocument7 paginiBalco Case NlsiuBhoomika GandhiÎncă nu există evaluări

- AIBE Study Material & Case Laws On Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR)Document7 paginiAIBE Study Material & Case Laws On Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR)aashishgupÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADR - Case LawsDocument6 paginiADR - Case LawskeerthivhashanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration Case LawDocument18 paginiArbitration Case LawRamanujam NammamlvarÎncă nu există evaluări

- BALCO v. Kaiser International Case AnalysisDocument11 paginiBALCO v. Kaiser International Case AnalysisAditi JeraiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lex Arbiter Is An International Principle Which Dictates That The Governing Law of The Arbitration Will BeDocument3 paginiLex Arbiter Is An International Principle Which Dictates That The Governing Law of The Arbitration Will BeRama KamalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Divyansh Agrawal UID - UG19-42Document15 paginiDivyansh Agrawal UID - UG19-42Divyansh AgarwalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Clarity Between Seat and Venue in Arbitration I. AbstractDocument5 paginiClarity Between Seat and Venue in Arbitration I. AbstractISHAAN MICHAELÎncă nu există evaluări

- BALCO Vs Kaiser - FinalDocument12 paginiBALCO Vs Kaiser - FinalHarneet SachdevaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adr PPT Module 2Document39 paginiAdr PPT Module 2binodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seat V VenueDocument7 paginiSeat V VenueSamiksha JainÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2818 2021 33 1501 27661 Judgement 20-Apr-2021Document106 pagini2818 2021 33 1501 27661 Judgement 20-Apr-2021Richa KesarwaniÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996: An IntroductionDocument25 paginiArbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996: An IntroductionupendraÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dhbcxfcii. The Problems With The Review of Arbitral Awards in IndiaDocument3 paginiDhbcxfcii. The Problems With The Review of Arbitral Awards in IndiaShivamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adr NotesDocument39 paginiAdr NotesAveakGangulyÎncă nu există evaluări

- II. The Problems With The Review of Arbitral Awards in IndiaDocument3 paginiII. The Problems With The Review of Arbitral Awards in IndiaShivamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration Law and Landmark CasesDocument29 paginiArbitration Law and Landmark CasesRohan BhatiaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 20Document20 paginiSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 20Nisheeth PandeyÎncă nu există evaluări

- MANU/SC/0090/2016: Equiv Alent Citation: AIR2016SC 1285Document6 paginiMANU/SC/0090/2016: Equiv Alent Citation: AIR2016SC 1285Ashhab KhanÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ayesha Anand IRACDocument19 paginiAyesha Anand IRACAyesha AnanadÎncă nu există evaluări

- Note On Arbitration and Conciliation ActDocument75 paginiNote On Arbitration and Conciliation ActAdv Tehare GovindÎncă nu există evaluări

- Muqeet 2Document7 paginiMuqeet 2Matthew RothÎncă nu există evaluări

- Seat VS Venue of Arbitration The Necessity The Absurdity and The Road AheadDocument16 paginiSeat VS Venue of Arbitration The Necessity The Absurdity and The Road AheadShubham MadaanÎncă nu există evaluări

- ADR Unit-1 Reading MaterialDocument19 paginiADR Unit-1 Reading MaterialEarl JonesÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bharat Aluminium Co. Vs Kaiser Aluminium Technical ServicesDocument9 paginiBharat Aluminium Co. Vs Kaiser Aluminium Technical ServicesIsraa ZaidiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Int Comm Arbitration Document PDFDocument103 paginiInt Comm Arbitration Document PDFHemantPrajapatiÎncă nu există evaluări

- International Commercial Arbitration Notes & AnswersDocument9 paginiInternational Commercial Arbitration Notes & AnswersSme 2023Încă nu există evaluări

- Landmark Judgment On Interpretation of Commercial Contract: Lawweb - inDocument35 paginiLandmark Judgment On Interpretation of Commercial Contract: Lawweb - inanon_378445473Încă nu există evaluări

- National Thermal Power Corporation Vs The Singer 0825s930279COM630956Document13 paginiNational Thermal Power Corporation Vs The Singer 0825s930279COM630956WorkaholicÎncă nu există evaluări

- Case CommentDocument5 paginiCase CommentMahi raiÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bangladeshi Courts at Odds With ArbitrationDocument6 paginiBangladeshi Courts at Odds With ArbitrationOGR LegalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Hardy Exploration in The Light of SGS Soma CaseDocument5 paginiHardy Exploration in The Light of SGS Soma CaseBhuvneshwari RathoreÎncă nu există evaluări

- INDTEL CaseDocument4 paginiINDTEL CaseManisha SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- NTPC v. Singer CompanyDocument3 paginiNTPC v. Singer CompanyAbhishek DeswalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Adr ProjectDocument11 paginiAdr Projectpalakdeep peliaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Applicable Laws in International and Domestic Arbitration: Determination of Seat and Its Legal SignificanceDocument14 paginiApplicable Laws in International and Domestic Arbitration: Determination of Seat and Its Legal SignificancebinodÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jurisdiction of Arbitral Tribunal and Arbitral AwardsDocument15 paginiJurisdiction of Arbitral Tribunal and Arbitral AwardsSmriti SinghÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration High Court JudgementsDocument3 paginiArbitration High Court JudgementsBADDAM PARICHAYA REDDYÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arbitration Open BookDocument13 paginiArbitration Open BookMithun MenonÎncă nu există evaluări

- Dozco India vs. Doosan Infracore (2011) 6 SCC 179: (Petitioner)Document11 paginiDozco India vs. Doosan Infracore (2011) 6 SCC 179: (Petitioner)Pulkit MograÎncă nu există evaluări

- Legal Language Legal WritingDocument33 paginiLegal Language Legal Writingdeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- In The Court of Ld. District Judge, Tis Hazari, DelhiDocument10 paginiIn The Court of Ld. District Judge, Tis Hazari, Delhideepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lecture 9 Transmission MediaDocument34 paginiLecture 9 Transmission Mediadeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- How To - Bio - BriefDocument13 paginiHow To - Bio - Briefdeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Certificate Course On Introduction To CoDocument4 paginiCertificate Course On Introduction To Codeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 2 (B) - Articles 12, 13 14Document9 paginiModule 2 (B) - Articles 12, 13 14deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Conveyancing Assignment Set 1Document2 paginiConveyancing Assignment Set 1deepak singhal100% (1)

- Course Plan BO Prof.S.P.KalaDocument8 paginiCourse Plan BO Prof.S.P.Kaladeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- CCI GPay 26 (1) Order 2020Document39 paginiCCI GPay 26 (1) Order 2020deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 (D) - Vicarious LiabilityDocument6 paginiModule 3 (D) - Vicarious Liabilitydeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3: Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881: Certificate Course On Enforcement of Fundamental RightsDocument6 paginiModule 3: Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881: Certificate Course On Enforcement of Fundamental Rightsdeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Course Schedule and Completion Information: S. No. Modules Date 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6Document1 paginăCourse Schedule and Completion Information: S. No. Modules Date 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 1 (B) : An Overview To The Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881Document5 paginiModule 1 (B) : An Overview To The Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 2A PDFDocument13 paginiModule 2A PDFdeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 (B) - Articles 25 and 26Document5 paginiModule 3 (B) - Articles 25 and 26deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Certificate Course On Enforcement of Fundamental RightsDocument7 paginiCertificate Course On Enforcement of Fundamental Rightsdeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 (B) - Critical Analysis On How Relevant Is Tort Law TodayDocument5 paginiModule 3 (B) - Critical Analysis On How Relevant Is Tort Law Todaydeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 (C) - 27, 28, 29Document9 paginiModule 3 (C) - 27, 28, 29deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 3 (C) - More On Section 7Document3 paginiModule 3 (C) - More On Section 7deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Certificate Course On Corporate GovernanceDocument9 paginiCertificate Course On Corporate Governancedeepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- MODULE 4 (B) - Maturity (Section 25)Document4 paginiMODULE 4 (B) - Maturity (Section 25)deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Module 4 (B) - Jist of Articles 30, 31, 32Document8 paginiModule 4 (B) - Jist of Articles 30, 31, 32deepak singhalÎncă nu există evaluări

- Women Empowerment in Jammu and Kashmir: With Special Reference To Educational Status of Rural WomenDocument14 paginiWomen Empowerment in Jammu and Kashmir: With Special Reference To Educational Status of Rural WomenCentral Asian StudiesÎncă nu există evaluări

- CV & K3 Umum HandryDocument2 paginiCV & K3 Umum HandryTraditions Restaurant-andBakeryÎncă nu există evaluări

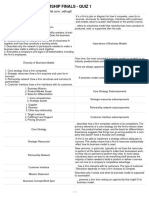

- Quiz 1 ReviewerDocument5 paginiQuiz 1 ReviewerJanella CantaraÎncă nu există evaluări

- 2 G.R. No. 178288 - Spouses Fortaleza v. Spouses LapitanDocument3 pagini2 G.R. No. 178288 - Spouses Fortaleza v. Spouses LapitanAndelueaÎncă nu există evaluări

- TDS Grossing Up Agreement To Gross Up Available - Sergi TransformersDocument6 paginiTDS Grossing Up Agreement To Gross Up Available - Sergi TransformersGOKUL BALAJIÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rulesregulationspart 2Document12 paginiRulesregulationspart 2alekhpÎncă nu există evaluări

- General Instructions On How To Accomplish The Online Practical ExercisesDocument4 paginiGeneral Instructions On How To Accomplish The Online Practical ExercisesManz ManzÎncă nu există evaluări

- Cases 3rd Page PDFDocument166 paginiCases 3rd Page PDFBANanaispleetÎncă nu există evaluări

- Group 3 P and V Assignment EditedDocument23 paginiGroup 3 P and V Assignment EditedFlorosia StarshineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Partnership OperationDocument10 paginiPartnership OperationchristineÎncă nu există evaluări

- Motion For Admission To Practice, Pro Hac ViceDocument2 paginiMotion For Admission To Practice, Pro Hac ViceChapter 11 DocketsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Checklist For Demerger DEVESH PANDEY CORDocument8 paginiChecklist For Demerger DEVESH PANDEY COR2050453 HARINI SUÎncă nu există evaluări

- P.O. Box 30031-00100, NAIROBI, KENYA. TEL: +254 20 2227461/2251355/07119445555/0732529995 E-MailDocument2 paginiP.O. Box 30031-00100, NAIROBI, KENYA. TEL: +254 20 2227461/2251355/07119445555/0732529995 E-MailLeinad OgetoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocument12 paginiBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledBryan Paulo CatiponÎncă nu există evaluări

- De Leon Vs EsguerraDocument7 paginiDe Leon Vs EsguerraApril BoreresÎncă nu există evaluări

- G.R. No. 253975Document6 paginiG.R. No. 253975Rap VillarinÎncă nu există evaluări

- Gender SocializationDocument14 paginiGender SocializationKainat JameelÎncă nu există evaluări

- Bmcmun '23 Chair GuideDocument29 paginiBmcmun '23 Chair GuidemÎncă nu există evaluări

- COURSE DESCRIPT-WPS OfficeDocument13 paginiCOURSE DESCRIPT-WPS OfficeRegie BacalsoÎncă nu există evaluări

- Judicial AffidavitDocument9 paginiJudicial AffidavitTalaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Armed Forces of The Philippines - WikipediaDocument63 paginiArmed Forces of The Philippines - WikipediaRodilla TijamÎncă nu există evaluări

- Jobs-865-Advertisement STA PDFDocument4 paginiJobs-865-Advertisement STA PDFShalin NairÎncă nu există evaluări

- Result MSC Nursing PDFDocument7 paginiResult MSC Nursing PDFvkÎncă nu există evaluări

- Constitution Unit 1 & 2Document28 paginiConstitution Unit 1 & 2shreyas dasÎncă nu există evaluări

- Skeleton ArgumentDocument4 paginiSkeleton ArgumentDerlene JoshnaÎncă nu există evaluări

- 23-1 ShackleDocument2 pagini23-1 ShackleAkhilÎncă nu există evaluări