Documente Academic

Documente Profesional

Documente Cultură

Fil Culturii

Încărcat de

Cristina CrsTitlu original

Drepturi de autor

Formate disponibile

Partajați acest document

Partajați sau inserați document

Vi se pare util acest document?

Este necorespunzător acest conținut?

Raportați acest documentDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Fil Culturii

Încărcat de

Cristina CrsDrepturi de autor:

Formate disponibile

Cultura libertii politice i arhitectura limitei

... afirmaia lui Tocqueville : Trecutul nu mai lumineaz viitorul, iar spiritul i croiete drum prin bezn .

Platon descria sfera problemelor umane tot ceea ce aparine convieuirii oamenilor ntr-o lume comun din

perspectiva ntunericului, a confuziei i a decepiei de care cei care aspira la adevrata existen trebuie s se

ndeprteze dac vor s descopere cerul clar al Ideilor eterne. Sfritul [acestei tradiii europene] a venit cu declaraia lui

Marx c filozofia i adevrul ei sunt situate nu n afara problemelor oamenilor i a lumii lor comune, ci exact n ele, i

c pot fi realizate numai n sfera vieii comune, pe care el o numete societate, prin apariia omului socializat ...

Sfritul a venit atunci cnd un filozof s-a ndeprtat de filozofie astfel nct s o realizeze n politic (H. Arendt).

Dimensiunea politic a arhitecturii. But what form can architecture define within the contemporary city without

falling into the current self-absorbed performances of iconic buildings, parametric designs, or redundant mappings of

every possible complexity and contradiction of the urban world? What sort of significant and critical relationship can

architecture aspire to in a world that is no longer constituted by the idea and the motivations of the city, but is instead

dominated by urbanization? In what follows I will attempt to reconstruct the possibility of an architecture of the city

that is no longer situated only in the autonomous realm of its disciplinary status, but must directly confront

urbanization. This possibility is put forward in two ways: first, by critically understanding the essential difference

between the concept of the city and the concept of urbanization how these concepts overlap, as well as how they

address two radically different interpretations of inhabited space and second, by looking at how urbanization has

historically come to prevail over the city. I will show the rise of urbanization not through its presumed real effects,

but through exemplary projects for cities, which here are understood as effective representations not simply of

urbanization itself but also of its logic. In an argument critical of the logic of urbanization (and its instigator,

capitalism), I will redefine political and formal as concepts that can define architectures essence as form ...

Aristotle made a fundamental distinction between politics and economics the distinction between what he defines as

techn politik and techn oikonomik. What he calls techn politik is the faculty of decision making for the sake of the

public interest decision making for the common good, for the way individuals and different groups of people can

live together. Politics in this sense comes from the existence of the polis (and not the other way around). The polis is the

space of the many, the space that exists in between individuals or groups of individuals when they coexist ... Political

space is made into the institution of politics precisely because the existence of the space in between presupposes

potential conflict among the parts that form it. This possibility is the very foundation of techn politik the art of

politics the decision making that must turn conflict into coexistence (albeit without eradicating the possibility of

conflict). Precisely because politics is incarnated in the polis the project of the city the existence of the polis holds

the possibility of conflict and the need for its resolution as its very ontological foundation. (...) Facing this scenario of

infinite urbanizationwhich today is no longer just theory but daily practice I would argue that the time has come

to drastically counter the very idea of urbanization. For this reason I propose a partisan view of the city against the

totalizing space of urbanization. In order to formulate a metacritique of urbanization as the incarnation of infinity and

the current stasis of economic power over the city, I propose to reassess the concepts of the political and the formal as

they unfold into an idea of architecture that critically responds to the idea of urbanization. In this proposal, the political

is equated with the formal, and the formal is finally rendered as the idea of a limit. Arendt writes, Politics is based on

the fact of human plurality. Unlike desires, imagination, or metaphysics, politics does not exist as a human essence but

only happens outside of man. Man is apolitical. Politics arises between men, and so quite outside man, she writes.

There is no real political substance. Politics arises in what lies between men and it is established as a relationship.

The political occurs in the decision of how to articulate the relationship, the infra space, the space in between. The

space in between is a constituent aspect of the concept of form, found in the contraposition of parts. As there is no way

to think the political within man himself, there is also no way to think the space in between in itself. The space in

between can only materialize as a space of confrontation between parts. Its existence can only be decided by the parts

that form its edges. (...) The task of architecture is to reify that is, to transform into public, generic, and thus

graspable common things the political organization of space, of which architectural form is not just the consequence

but also one of the most powerful and influential political examples. (...) An architecture that is defined by and makes

clear the presence of limits which define the city. An absolute architecture is one that recognizes whether these limits are

a product (and a camouflage) of economic exploitation (such as the enclaves determined by uneven economic

redistribution) or whether they are the pattern of an ideological will to separation within the common space of the city.

Instead of dreaming of a perfectly integrated society that can only be achieved as the supreme realization of

urbanization and its avatar, capitalism, an absolute architecture must recognize the political separateness that can

potentially, within the sea of urbanization, be manifest through the borders that define the possibility of the city 1.

Pier Vittorio Aureli, THE POSSIBILITY OF AN ABSOLUTE ARCHITECTURE, Massachusetts, 2011

S-ar putea să vă placă și

- Design InteriorDocument1 paginăDesign InteriorCristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pac, Dde, Pug, Puz, PudDocument7 paginiPac, Dde, Pug, Puz, PudRadu MoisescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Desen 45Document1 paginăDesen 45Cristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Drept Urban-Curs 9Document7 paginiDrept Urban-Curs 9Alexandra ArdeleanuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Compozitie UrbanaDocument3 paginiCompozitie UrbanaTheya TranceAddictÎncă nu există evaluări

- Leg Ce Tre Sa Contina Cererea de Emitere A Autorizatiei de ConstructieDocument1 paginăLeg Ce Tre Sa Contina Cererea de Emitere A Autorizatiei de ConstructieVlad DulcescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Pentru Emiterea Certificatului de UrbanismDocument1 paginăPentru Emiterea Certificatului de UrbanismRadu MoisescuÎncă nu există evaluări

- Lege 50Document10 paginiLege 50Cristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arhitectura PeisajuluiDocument78 paginiArhitectura Peisajuluiflorinursu180% (5)

- Capitol4 5Document2 paginiCapitol4 5Cristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- LEGE Nr2Document211 paginiLEGE Nr2Cristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filoz CultDocument1 paginăFiloz CultCristi VasilacheÎncă nu există evaluări

- Filoz CultDocument1 paginăFiloz CultCristi VasilacheÎncă nu există evaluări

- PEISAGISTICADocument48 paginiPEISAGISTICACristina Crs100% (2)

- CursSVoiculescu AntichitateaDocument125 paginiCursSVoiculescu AntichitateaCristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- CursSVoiculescu EvulMediu PDFDocument94 paginiCursSVoiculescu EvulMediu PDFCristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Arhitectura PeisajuluiDocument78 paginiArhitectura Peisajuluiflorinursu180% (5)

- FIL CultDocument2 paginiFIL CultCristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghid ArchicadDocument640 paginiGhid ArchicadVisan Roxana CristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

- Ghid ArchicadDocument640 paginiGhid ArchicadVisan Roxana CristinaÎncă nu există evaluări

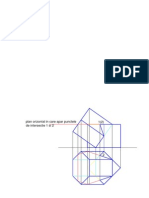

- Plan Orizontal in Care Apar Punctele de Intersectie 1 Si 2 1Document1 paginăPlan Orizontal in Care Apar Punctele de Intersectie 1 Si 2 1Cristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- Rimetea DeclaratiaDocument2 paginiRimetea DeclaratiaCristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări

- 11 SferaDocument4 pagini11 SferaCristina CrsÎncă nu există evaluări